The 1876 Centennial International Exposition in Philadelphia—the first world’s fair held in the United States—was an international success and demonstrated the rising prominence of the U.S. in the world. The intellectual fervor of the time eventually led to the founding of the Penn Museum in 1887, the first global institution at Penn. The Museum made the world its purview, and its field research program distinguished it among its peers.

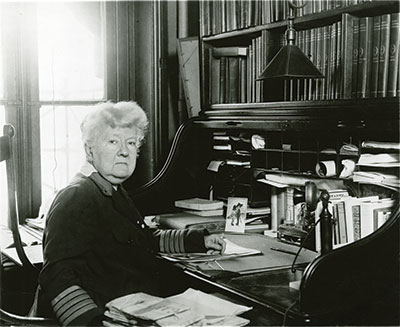

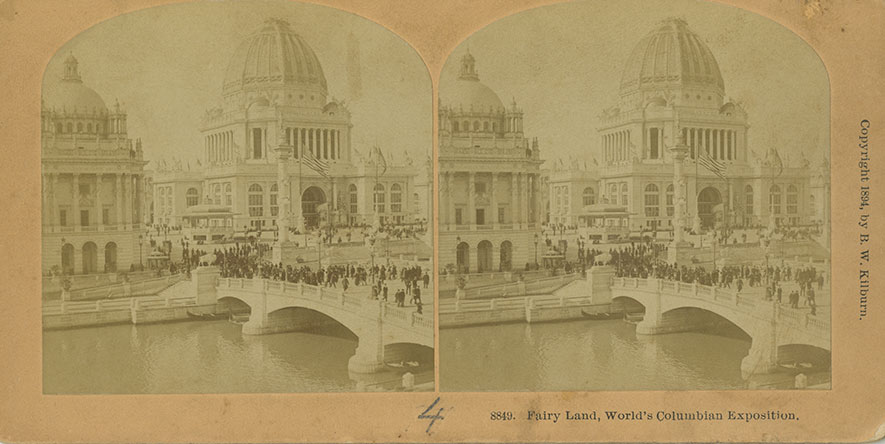

The Penn Museum exhibition at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair. Photographs by Jas. H. Caldwell. UPM image #174652.

Stewart Culin: Innovator in Exhibit Design

Soon after the Museum was established, it was asked to play a role in several other world’s fairs. Stewart Culin, who was hired in 1890 as Secretary of the Board and later became Director of the Museum, was a pioneer of exhibit design. The Museum’s exhibits were praised for their clear labels (not a standard practice at the time), and Culin opened the first “blockbuster” in 1892, a loan exhibition titled Objects Used in Worship. Yet it was at the world’s fairs that Culin and the Museum made a sensation.

In the fall of 1892, the Museum was asked to participate in the Exposición Histórico-Americana in Madrid. is world’s fair, and the 1893 fair in Chicago, celebrated the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ arrival in the Americas. Nations from the Americas brought nearly 200,000 antiquities to Spain to represent the pre-Columbian era. Many of these objects were also exhibited at the Chicago World’s Fair. The Penn Museum displayed a number of important prehistoric stone tools from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Ohio, and Florida. Appointed Secretary of the United States Commission, Culin also prepared the exhibits for the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (selections from the Samuel George Morton collection of skulls, today held at the Penn Museum) and the Numismatic and Antiquarian Society of Philadelphia. Daniel G. Brinton, a founder of the Museum as well as an early figure in American academic anthropology, was also appointed a member of the United States Commission. In January 1893, the Museum received the highest award from the Exposition for Culin’s efforts: one of seven gold medals awarded to exhibits from the U.S. The Academy and Numismatic Society exhibits both earned silver medals.

By April 1893, Culin was in Chicago to prepare exhibits for the World’s Columbian Exposition. He worked on “Department of Anthropology” exhibits, under the direction of Harvard’s Frederic Ward Putnam. Brinton also attended the fair, and presided over the concurrent International Congress of Anthropology.

Sara Yorke Stevenson, Stewart Culin, and Additions to the Museum Collection

Sara Yorke Stevenson, a woman of remarkable energy and talents—another founder of the Penn Museum and the first Curator of the Egyptian and Mediterranean Sections—also prepared an exhibit at Chicago on Egyptian archaeology. A special act of Congress was required to allow her, as a woman, to serve on the Jury of Awards for Ethnology at the Chicago Exposition.

The Penn Museum again garnered gold medals for its exhibits on Objects from the Flinders Petrie Excavations and the Egyptian Exploration Fund, Objects Illustrative of Religious and Social Customs of Chinese in the United States, and Charms, Amulets, and Folklore Objects. No other American institution was represented by work in Old World archaeology. Culin also displayed games from all over the world using an evolutionary perspective, showing the connections between religion, divination, and games of play.

The Museum acquired important collections from the Chicago Fair, including the famous Hazzard collection of Basketmaker artifacts from the American Southwest (purchased with funds from Phoebe Hearst), the Ecuadoran collection (which included portions of the Guatemalan exhibit), and more games. Culin published one of his major monographs after the Fair, on Korean Games Cards, still a useful reference today. The Exposition Universelle in Paris (1900) also awarded a grand prize to the Penn Museum exhibit, in the category of higher instruction. Out of 900 entries in this category, 64 grand prizes were awarded, nine to the United States.

With the death of William Pepper (University Provost and later President of the Board of Managers at the Museum) in 1898, and especially that of Brinton in 1899, Culin lost his major supporters at the Museum. Culin’s constant disagreements with Stevenson and other curators led the Board to abolish the directorship in 1899, and eventually forced his departure to the Brooklyn Museum (1895), with the help of Pak Young Kiu, the Secretary of the Korean Commission to the Columbian Exposition.

An interesting anecdote from Chicago described an attempt by the Museum to hire Franz Boas to develop a Section of Ethnology and Anthropology at the Museum. Stevenson met Boas, unemployed at the time, at the Fair and was impressed by him. Despite Stevenson’s and the Museum’s efforts, however, including a proposal for a joint appointment with the Wistar Institute of Anatomy, Boas’ salary demands proved too high. Boas later joined Columbia University and the American Museum of Natural History, where he revolutionized the field of anthropology.

Culin repeated his exploits at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta in 1895. His gold medal exhibit on games resulted in a comprehensive catalogue published by the Smithsonian, Chess and Playing Cards, still a useful reference today. The Exposition Universelle in Paris (1900) also awarded a grand prize to the Penn Museum exhibit, in the category of higher instruction. Out of 900 entries in this category, 64 grand prizes were awarded, nine to the United States.

With the death of William Pepper (University Provost and later President of the Board of Managers at the Museum) in 1898, and especially that of Brinton in 1899, Culin lost his major supporters at the Museum. Culin’s constant disagreements with Stevenson and other curators led the Board to abolish the directorship in 1899, and eventually forced his departure to the Brooklyn Museum in 1903. It was at Brooklyn that Culin’s museum philosophy was allowed to fully blossom. Upon his death in 1929, one newspaper cited him as “Dr. Culin, Who Tried to Make Museums Attractive.”

The Penn Museum also attended the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis in 1904. The Museum purchased some collections, notably the mastaba of Kaipure (see David Silverman, this issue), but George Byron Gordon, who had succeeded Culin at the Museum, was not impressed. Stevenson wrote back to Gordon: “I am sorry to hear that you are not likely to derive much benefit from your purchasing expedition to St. Louis. I think Expositions are ‘tapped out’. But I hoped that others did not think so and that you might gather in some spoils.”