A scholar with many interests, including the archaeology of the Indian subcontinent, University of Pennsylvania Professor W. Norman Brown (1892–1975) was one of the great institution builders for the study of India’s past. On September 6, 1922, R. V. D. Magoffin of the Archaeological Institute of America wrote to Brown to appoint him their representative in India, expressing their hope that he might establish an American School of Classical Studies there.

His appointment coincided with the earliest excavations at Mohenjo-daro—one of India’s most ancient cities—and the discovery of the Indus or Harappan Civilization. But as an American, Brown faced stiff opposition, as so-called foreign archaeologists were not welcome to excavate in British India. The Viceroy, Lord Curzon, summed it up succinctly when he declared, “We will excavate our own sites.”

Yet despite this bias, Brown successfully proposed the establishment of The School of Indic and Iranian Studies, and received a favorable reception from the Government of India in 1927–28.

The Penn Museum’s interests in India first appear in our Museum Archives in 1930, when then Museum Director Horace H. F. Jayne (1929–1941) mentioned Brown in his correspondence with Ernest J. H. Mackay, the Director of the Mohenjo-daro excavations (and, for a short time, an employee of the Museum’s Egyptian Section during Clarence Fischer’s excavations in Palestine at Beth Shan). Seeking to conduct archaeological excavations in India, Jayne sought Mackay’s opinion. Although Mackay reiterated that the antiquities laws of India would not permit a ‘foreign’ excavation; he also suggested that this might change in the near future.

In 1932, India’s Antiquities Law was indeed amended. Since Brown was a specialist in Sanskrit, untrained in excavation, he decided to recruit Mackay to be his field director. Contact between these two men began in earnest in 1934. On April 7, 1934, Brown wrote to Mackay that “We have long felt that we should like to see an American archaeological expedition in India, [ideally in] the Indus Valley or possibly Baluchistan.”

On April 18, 1934, Mackay responded that he would be happy to lead an American expedition. He mentioned a number of possible excavation sites in the Indus Valley, including Ali Murad, Ghazi Shah, and Chanhu-daro, as well as Nal in Baluchistan, but his first choice was a place known as Amri, just south of Mohenjo-daro. He suggested a five-month field season there at a cost of £3,280, or about $17,000, including his own salary.

Funding was an issue due to the Great Depression, and Brown sought to form a consortium of museums to undertake the project and share in the finds. Brown had in mind the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (MFA), the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Toledo Museum of Art, the Worcester Museum of Art, and the Penn Museum, noting that “If all these museums come in, we shall be embarrassed with too much money.”

In May 1934, Brown sent a six-page proposal for the Amri excavation, including Mackay’s budget, to Ananda Coomaraswamy, his contact at the MFA, who endorsed the project. On June 7, 1934, Brown personally pleaded his case before the MFA’s Museum Committee. The minutes of their meeting record that they voted for “the museum [to] appropriate $17,000 for one year’s excavation at a site in the Indus Valley. . . .” Thus, the MFA became the sole financial supporter of the proposed expedition and its sole beneficiary.

With his money in hand Brown opened correspondence with the Archaeological Survey of India, hoping to excavate during the full season of 1934–35. Since this was an important and delicate matter, Brown traveled to India to conduct the negotiations, arriving August 23, 1934. His plans for doing research were frustrated, however, since the following year was devoted mostly to the agonizing process of securing the permit to dig. Although the Antiquities Law had been changed, the rules for implementing it were not yet formalized, and as the first application under these new rules, Brown’s permit would set the precedents for foreigners and archaeological excavation.

On September 15, 1934, these rules were at last published in The Gazette of India. This coincided with the early appearance of N. C. Majumdar’s monograph Explorations in Sind. Under Mackay’s tutelage Majumdar had conducted the first systematic exploration in the lower India Valley and had visited all of the sites mentioned in the negotiations with Brown. In fact, Majumdar had conducted a test excavation at Amri and his book had a disagreeable revelation about the site. Brown telegraphed Mackay in England on September 11, 1934, reporting: “Proofsheets Majumdar’s report . . . available today state Mohammadan [Islamic] graves top Amri mound, villagers objected excavation, he could only explore edges STOP Therefore chances our excavation imperiled STOP Would Chanhu-daro be acceptable . . . .”

After a flurry of correspondence, Brown, Mackay, and the MFA agreed that Chanhu-daro was the preferred option and the formal application for excavation was duly amended to reflect this new preference.

The license to excavate was finally granted on April 3, 1935, only a few weeks before Brown’s departure from India on May 17, 1935. The Director General of the Archaeological Survey of India, J. F. Blakiston, in writing to Brown, notes: “I do not see any special urgency in the matter of sending the license which I have already promised you . . . and it will in any case be given to you on your return to India or to Dr. Mackay as may like when ready and before commencement of the work.” Given the time and energy that Brown had spent securing this license, one might well wonder if he shared the Director General’s lackadaisical attitude.

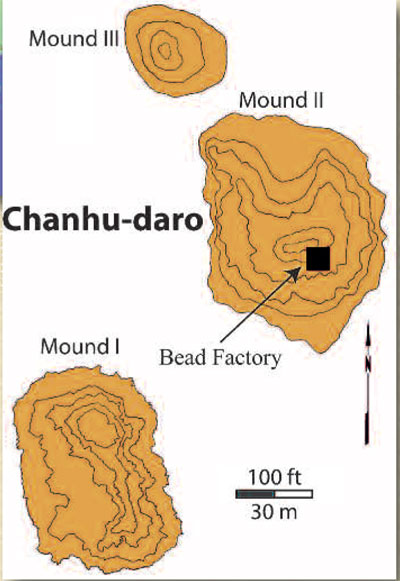

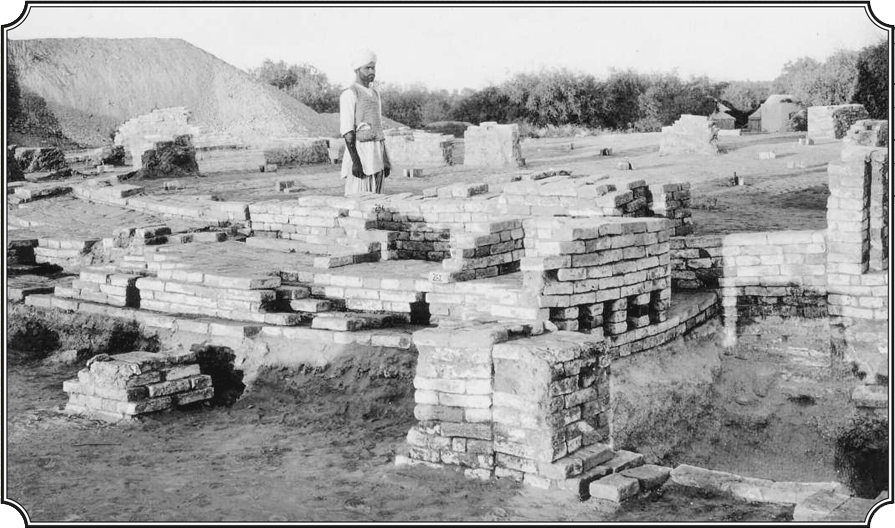

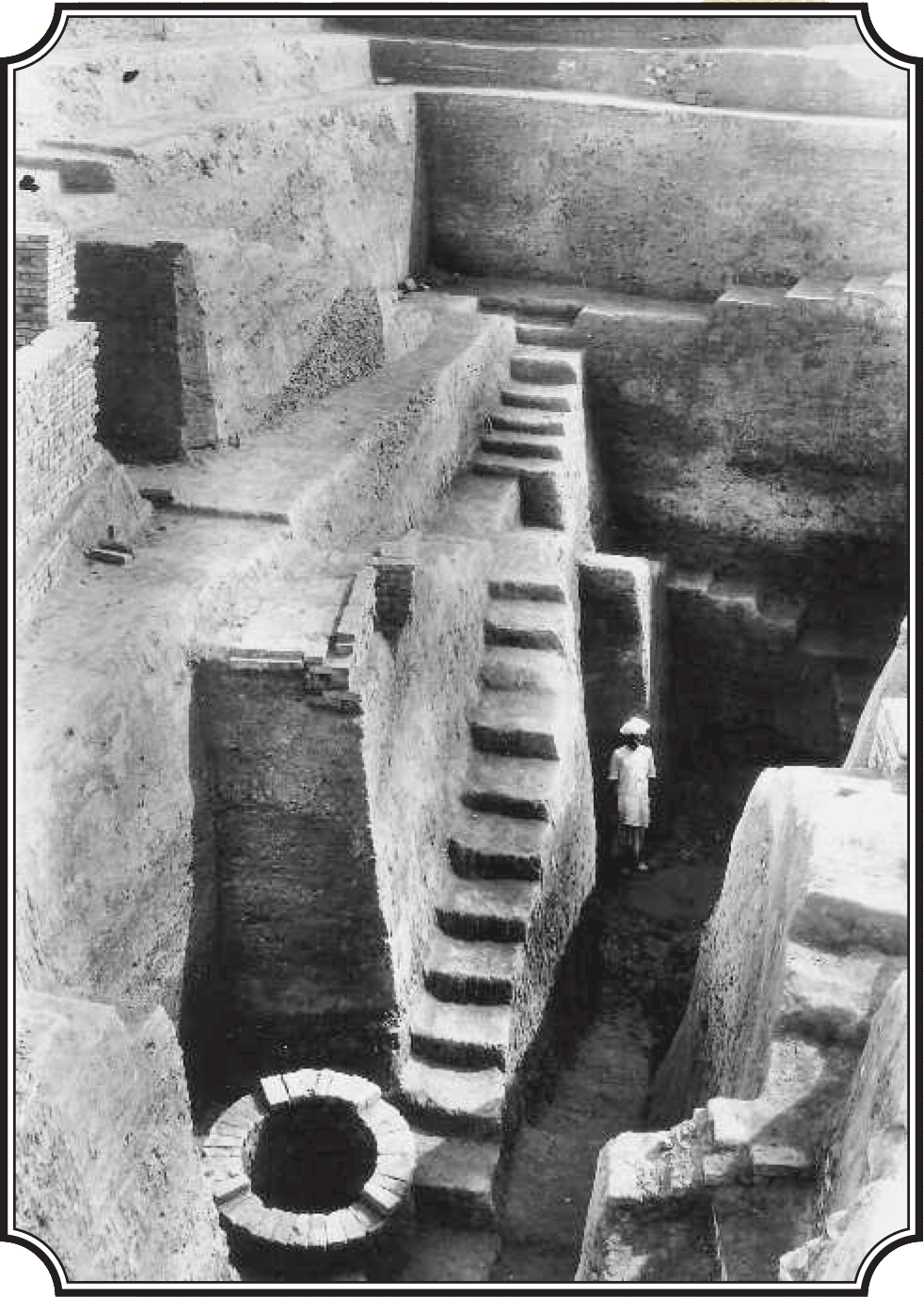

Mackay arrived at Chanhu-daro on October 23, 1935, to begin his excavations. Over the course of the field season he found evidence for a considerable amount of craft activity at the site during the Harappan period (2500–1900 BC). This technological evidence included material related to the making of beads and square stamp seals, making Chanhu-daro an important site for understanding Harappan technology.

Mackay also investigated the Post-urban Harappan levels at the site (1900–1500 BC) and, in particular, his exposure of the remains of the Jhukar habitations and even materials of the so-called Jhangar and Trinhi Cultures are very interesting. Although these materials are still not well understood, Chanhu-daro remains the best-documented excavation for their study—however inadequate it may be—providing clues to the emergence of the Post-urban Harappan in Sindh.

Following his excavations, Mackay and his wife Dorothy— herself an author who dealt with the Indus Civilization—left India for good on April 23, 1936. His final report on Chanhu- daro was published in 1943, just prior to his death.

The MFA’s share of the finds from Chanhu-daro reached Boston about June 1, 1936. While comprising a fine collection of Indus material—including seals, some wonderful painted pottery, copper and bronze implements, and important evidence for Harappan craftsmanship and technology—the artifacts were not exactly the sort of material about which an internationally renowned art museum would be enthusiastic. Although Mackay’s conduct of the excavation and his administration of the project received praise, there was little excitement about the finds. Given the ongoing Great Depression and other potentially more attractive projects, was Chanhu- daro worth supporting?

The MFA’s Museum Committee discussed this during its meeting on March 5, 1936, and on April 2, they recommended that support for the Indus Valley Expedition “not continue beyond the present season.” The MFA then turned its attention to Persepolis in Iran, undertaking a joint project there with the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

Despite this conclusion, W. Norman Brown laid the foundations for future American archaeological work in the Indian subcontinent. Today, there are five American excavations active in India and Pakistan and many students conduct their dissertation fieldwork there every year. Although it was something of a saga to get it all going, in the end Penn’s Professor Brown certainly succeeded.

Mackay, Ernest John Henry. Chanhu-daro Excavations, 1935–1936. New Haven, CT: American Oriental Society, 1943.Mackay, Ernest John Henry [Revised by Dorothy Mackay]. Early Indus Civilizations. 2nd ed. London: Luzac & Co, 1945.

Majumdar, N. G. Explorations in Sind. Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, 1934.

Possehl, Gregory. The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Walnut Creek, CA: Alta Mira Press, 2002.

Roy, Sourindranath. The Story of Indian Archaeology 1784–1947. Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, 1961.