On May 18, 1539, the Spaniard Hernando de Soto embarked on an expedition to explore what is now the southeastern United States. The journey was long and bloody. Before the expedition ended in September of 1543, several thousand Indians had been killed, as well as de Soto himself and half of his 600-man force. Ironically, while de Soto’s men brutally attacked and plundered the Indians, his chroniclers amassed a wealth of information in their detailed descriptions of the Southern tribes. Of particular interest is the chroniclers’ account of de Soto’s meeting with Tascalusa, Chief of the Mobile tribe, in the autumn of 1540. Tascalusa, seated on cushions and surrounded by attendants, wore “a pelote or mantle of feathers down to his feet. His head was “covered by a kind of coif like the almaizal, so that his headdress was like a Moor’s which gave him an aspect of authority” (Bourne 1904, 2:120).

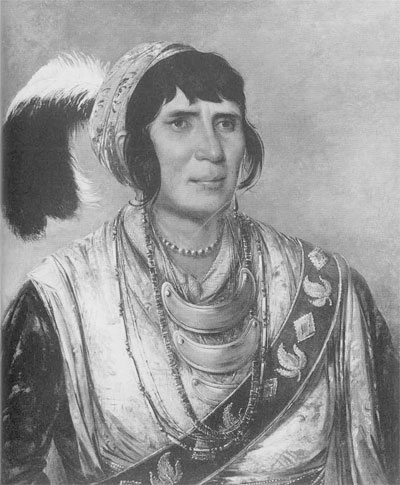

National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr.

Feather mantles like that worn by Tascalusa were made by Native Americans from Virginia to Louisiana. These garments were also called matchcoats, from an Algonkian word, matshîgode, meaning cloak, robe, or mantle. Feather matchcoats, worn by both men and women during warm weather as an emblem of social status, were made by weaving feathers into a fiber net. Turkey, swan, or duck feathers could be used, and in some areas the heads of mallard ducks were also woven into the mantles. The resulting garment was lightweight, warm, and very beautiful (Fig. 2). Leaders among the Southern Indians also wore distinctive feather headdresses, such as crowns or turbans made of animal or bird skins decorated with eagle or turkey tail-feathers, tufts of down, or bird wings.

The Southern Indians began to alter their style of dress soon after their first encounters with Europeans. By the late 18th century, most of the tribes were making their matchcoats, turbans, and other garments out of European cloth (Fig. 1). Only the Parnunkey Indians of Virginia retained the technology for making the intricate feather mantles and headdresses that so impressed de Soto (Knifemen, Gregory, and Stokes 1987:157). Today the Southern Indians appear to use feathers sparingly compared to other Native North Americans. However, despite five centuries of intense and often traumatic culture change, feathers continue to play an integral, if subtle, role in Southeastern ceremonialism.

Cultural Heritage of the Southern Indians

Southeast Indian ethnology is extraordinarily complex, partly because of the tremendous ethnic and linguistic diversity of the region: there may at one time have been over 150 separate tribes and languages (Fig. 3). The dominant language family of the area is Muskhogean, dialects of which are spoken by the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, Seminole, Natchez, and many smaller tribes. Other language families represented include Iroquoian (Cherokee and others), Yuchean (Yuchi), Siouan (Ofo, Biloxi, Quapaw, and others), Algonkian (Shawnee and others), Tunican (Atakapa, Chiti-macha, and Tunica), and Caddoan (Caddo and others).

Southeastern ethnology became further complicated through culture change, large-scale migrations, and shifting demographics, which occurred as a result of contact with Europeans during the 17th and 18th centuries. In the early 19th century, the United States government formally initiated an aggressive campaign to assimilate the Southern Indians. Government agents encouraged the Southern tribes to adopt the English language and EuroAmerican customs; the work of Christian missionaries supported this effort. Beginning in the 1830s, the government forced most Southern Indians to move to Indian Territory, west of the Mississippi River. EuroAmericans referred to this migration as the Removal, but the Indians themselves called it the Trail of Tears, because of the unspeakable hardships they suffered. In 1907 Indian Territory became the state of Oklahoma; this entailed the destruction of independent tribal governments and necessitated further accommodations to the dominant culture.

Drawn by Jon Snyder after Hudson 1976: Map 1.

In spite of the ethnic, linguistic, and historic welter, Native peoples of the Southeast share many traits that derive from their common cultural ancestry. Most Southern Indians are descendants of the culture that flourished for a thousand years, beginning about 700 C.E., in the valleys of the Mississippi River and its major tributaries. Mississippian culture, as it is called, was characterized by monumental earthen temple mounds with flattened tops and intricate ceremonial and domestic arts (Howard 1968). The Mississippians practiced horticulture; maize constituted their main crop, but they grew beans, squash, pumpkins, and a variety of other crops as well. They supplemented this diet through hunting and fishing.

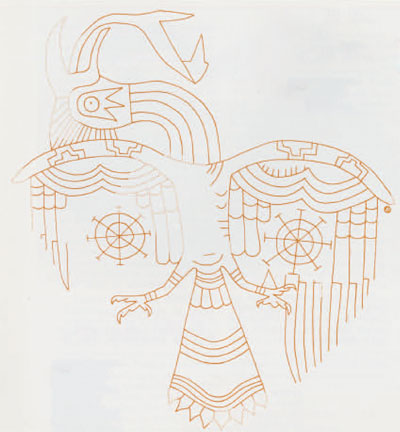

The Mississippians performed religious rituals known to archaeologists as the Southern Cult or the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex. Birds were central to the ideology of this ceremonial complex, which included representations in visual media of eagles, hawks, turkeys, and woodpeckers, as well as depictions of humans dressed in bird costumes (Galloway 1989; see Fig. 4). These birds were symbolically associated with war and they were believed to have powerful supernatural counterparts in the spirit world, whose assistance could be invoked through.

From Phillips and Brown 1978: opp. Pl. 85; reproduced by permission of the Peabody Museum, Harvard University.

Birds, Feathers, and Ritual in Southeastern Cultures

Birds of various species—and their feathers—remain central to the ideology and ritual life of Southern Indians. Southeastern origin narratives and animal stories feature such actors as Owl, Buzzard, Heron, Hummingbird, Kingfisher, and Turkey (Swanton 1913). These characters represent spirit beings whose attributes parallel those of their bird counterparts. Feathers are also considered to be spiritual agents of great power, as demonstrated by a Cherokee narrative on the origin of corn and game. In this story, a boy endowed with supernatural powers changes himself into a down feather and allows himself to be carried about by the wind in order to achieve his purposes (Mooney 1888).

Native Southeastern healers use feathers in many ways. Formerly, Seminole shamans accompanied curing songs with a terrapin shell rattle decorated with cowl feathers and down (Howard 1984:72). Seminole healers now wear feathers in their hatbands to indicate their areas of specialization. A flicker feather signifies the ability to cure headaches, a buzzard feather the ability to cure bullet wounds, and an owl feather the ability to cure several different illnesses (Howard 1984:74). Similar associations are made by Creek healers.

Southern Indians also use feathers to decorate paraphernalia employed in contemporary ceremonies. The two most important rituals performed by most Southern Indians are the Green Corn ceremony and the Ball Game cycle. The Calumet ceremony, which survives among the Cherokee as the Eagle Dance, was also widespread among the Southern tribes in the early contact years. The following paragraphs discuss the decorative use of feathers in the ritual paraphernalia of these three ceremonies.

From Speck 1909, Pt. 7. University Museum neg. G6-14230

The Green Corn Ceremony

The Green Corn ceremony or Busk, an abbreviation from the Creek word boskita, is now performed by the Creek, Yucbi, Natchez, and Seminole. The Busk is an annual ceremony of renewal, usually held in July to mark the first ripening of the year’s corn crop. The ceremony traditionally lasted four days, although now it may be performed over a weekend, beginning on Friday night. It takes place at a square ground, a sacred outdoor area whose perimeter is defined by brush arbors. The square ground is prepared and maintained through prescribed rituals. The ceremony itself involves several components, including feasts, orations, purification rites, the Ribbon Dance, the Feather Dance, Stomp Dances, and other elements.

In order to prepare for the Busk, participants must purify themselves through the use of emetics and scratching or ritual scarification. Participants have their arms and/or legs scratched as a means of promoting strength and general health. Only shamans manufacture and use scratchers, which resemble short combs made of sharpened turkey bone splinters or pins attached to the quill of a feather. The barbs of the feather may be retained on the shaft to ornament the scratcher (Fig. 5).

The Ribbon Dance, also called Women’s Dance because it is performed by women, traditionally takes place during the daytime on the first day of the Husk. The line of women dancers is led into the dance ground by two men each carrying a wooden stick, approximately one yard long, decorated at the top with two or more pendant white crane feathers (Fig. 6). A male singer and his two assistants provide musical accompaniment for the Ribbon Dance; each wears a long white crane feather in his hat. The two assistants each play a sacred coconut shell rattle which has a tassle of white crane feathers tied to its handle (Howard 1984:118-119). The crane and the color white symbolize peace among many Southeastern tribes. The woman who leads the Ribbon Dance carries an atassa or war club knife in her right hand. The handle of the atassa is decorated with white crane feathers (Seminole) or a golden eagle feather (Creek); it is used to ward off evil spirits (Howard 1968, 1984). The leading woman also carries a fan made of turkey tail feathers in her left hand (Fig. 6).

The Feather Dance, traditionally performed on the third day of the Busk, represents the climax of the ceremony. The anthropologist Frank Speck wrote that for the Yuchi, this dance “symbolized the journey of the sun over the square-ground. The Sun deity was believed to be closely watching the dance from above. Should it not be properly enacted he was likely to stop in his course, according to the belief” (1909:126). James Howard added that the Creek dedicate the Feather Dance to the “Powers Above” and that all of the songs that accompany the dance refer to birds (1968:95).

Among the Seminole, members of the Bird clan are charged with preparation of the feather sticks used in the Feather Dance, and they direct its performance. The ritual “calling of birds” precedes the Feather Dance:

A young man of the Bird clan, known as the tafu impehku (feather whooper), carrying a short (two feet in length) wand with four white crane feathers attached to its tip, walked once around the fire in a counterclockwise direction and thence to the tajo or small mound at the northeast corner of the square ground. Standing atop it and facing east, he lifts the wand heavenward and cries “Weeeel” four times. This is to advise the various species of birds that a dance is about to be performed in their honor. (Howard 1984:138-9)

Museum Object Number(s): 46-6-9

Each Feather Dancer carries a feather stick made of a piece of river cane or wood, approximately five feet in length. White and blue crane feathers are strung alternately down about half of the stick, starting from the top. The dancers wave their feather sticks back and forth while dancing in place. Howard observed that “the swaying of the feathered wands in time with the music creates the odd illusion of a flock of small birds hovering just above the dancers’ heads” (1984:141). The Feather Dance is repeated four times, four being the sacred number for most Southern Indians.

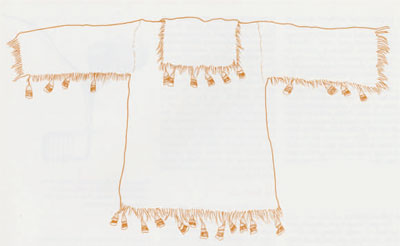

Stomp Dances are usually performed at night during the Green Corn ceremony, as well as on other occasions during the year. These dances are less formal and more social in nature than the daytime dances. Typically, various men take turns leading Stomp Dance sets; each set includes several short Stomp Dances performed in a continuous succession. In the early 20th century, Yuchi men evidently carried feather fans while leading Stomp Dances. The fans were made by perforating the quills of turkey buzzard or eagle tail feathers and stringing them together side by side at the base (Speck 1909:52; see Fig. 6). Aside from identifying the leader of a particular set of Stomp Dances, the dancer used the fan to emphasize his gestures, to keep insects away, and to protect his eyes from the glare of the fire (Speck 1909:125; Swanton 1928:683). Men often wore special shirts during the Stomp Dance, some of which may have been decorated with feathers (Fig. 7).

The Ball Game

The other major ritual still performed by Native Southeasterners is the Ball Game. Stickball, the forerunner of lacrosse, is played in some form by virtually all of the Southern Indians. It is much more than a game by European standards, however. Ball play traditionally served to maintain cosmic balance and peace through the symbolic enactment of conflict and resolution. The ritual complex that frames ball play may include scratching, a special daytime dance, medicine rites performed by a shaman, betting, orations, feasts, and night dances. Originally, the Ball Game constituted part of a larger ceremonial cycle that lasted several days. Some tribes, such as the Yuchi, incorporated ball play into the Green Corn ceremony.

Museum Object Number(s): 46-6-8

Museum Object Number(s): 46-6-7

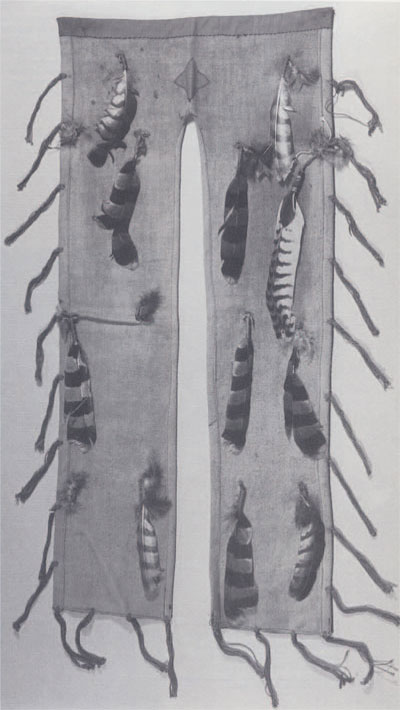

Birds and feathers are prominent symbols in the Ball Game, especially as performed by the Cherokee. The Cherokee narrative on the origin of ball play tells how the flying animals defeated the four-footed creatures (Mooney 1890:108-109). The singer for the Cherokee Ball Player’s Dance accompanied himself with a gourd rattle decorated with an eagle or hawk feather (Speck and Broom 1983:57). Cherokee ball players wore a “tail” or a pendant of feathers that was suspended from the rear of a belt (Speck and Broom 1983:55). The tails were made of hawk, white goose, or eagle feathers, all of which symbolized speed and strength (Figs. 8,9).

A member of the Bird clan was responsible for collecting and ritually preparing feathers to be worn by Cherokee ball players (Fogelson 1971:334):

Each player identified with a different species of bird on the basis of his particular playing skills or position on the field. Thus the center fighter, who was usually the strongest player on the team, wore eagle feathers, after the legendary captain of the bird team. Other players might choose a specific bird known for its swiftness, its agility, or its ability to pick up objects. The wearing of tails in the dance or in the game has long since faded from memory, but players still attach feathers to their hair or to their ball sticks. (Fogel-son 1971:334; see Fig. 11)

From Speck and Brown 1983, Pl. 16a. Reproduced courtesy of the American Philosophical Society

Seminole and Creek ball players also attach one or two feathers to their hair by means of a horsehair roach, which is tied to a scalplock at the back of the head (Howard 1984: 188).

Early in the 20th century, some Oklahoma Choctaw ball players wore a cloth beanie with appliqué designs around the rim. A stiff cloth tab was sewn onto the center of the cap, to which a feather was tied; the feather twirled every which way as the player ran. The cap could be fastened to the player’s head by means of a chin strap. Choctaw ball players also acquired affectionate, often humorous nicknames that reflected their competitive attributes, such as bakbak (woodpecker), opa (owl), and shikl (buzzard).

Cherokee Eagle Dance

The Cherokee Eagle Dance derives from the calumet or pipe ceremony that was probably performed by most Southern Indians at one time. Tobacco was integral to Southeastern cultures and was used in curing and religious rituals; thus the calumet was significant as an article of ceremonial paraphernalia. An anonymous 18th-century French author described a Choctaw ritual pipe made of red stone with a stem about two or three feet in length.

Red feathers were mounted in a fan shape on the pipe stem; the stem also had eight or ten black and white feathers hanging from it (Swanton 1918:67). Other European explorers described ritual calumets similarly decorated with feathers among the Creek, Natchez, and other tribes.

Museum Object Number(s): 46-6-11

The Cherokee are the only Southern tribe that retained the Eagle Dance, a remnant of the calumet ceremony, into the 20th century. The Eagle Dance is a winter ceremony; it symbolizes peace and is performed over the course of one night. For this dance, each performer carries an eagle-feather wand that resembles a calumet without the pipe bowl (Fig. 10). Speck described the wand as follows:

Eagle-feather wands are made of a rod of sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum) approximately 21 inches long and 1/2 inch wide, to which is lashed an arch of the same material to serve as a frame for five bald eagle feathers, about 12 inches long, fastened by inserting the quills through holes in the arch so that they spread out like a fan. The sourwood is “sacred” to the eagle rites and prevents contamination when handling the bird and its feathers. (Speck and Broom 1983: 39)

Cherokee eagle-feather wands serve as emblems of peace; the dancers use the wands to complement their gestures in various parts of the choreography.

Conclusions

Since Mississippian times, the Southern Indians have honored birds and their supernatural counterparts through ritual and have used feathers as agents of spiritual power. The importance of birds in Southeastern thought is reflected in the origin narratives and animal stories that abound in the folklore of this region. Feathers, while employed with restraint compared to tribes from the Southwest or Plains areas, retain their decorative and symbolic functions in contemporary Southeastern ceremonies such as the Busk, the Ball Game, and the Eagle Dance. Thus, five hundred years after de Soto, avian metaphors continue to represent a central component of Southeast Indian cosmology, religion, and aesthetic expression.