There is a story that when Christopher Columbus, after his second voyage to the New World in 1494, was asked to describe the new island he had found in the west, he crumpled a sheet of paper and set it before the Spanish king and queen. The Caribbean island was Jamaica, with its magnificent and craggy mountains. Though this story, like many such anecdotes, has been told of other explorers and other places throughout the New World, it helps us to understand how, a few centuries later, a relatively small number of fugitive slaves could very nearly bring Jamaican planter society to its knees. The rugged mountains made the interior of the island an ideal refuge for slaves who, in the 17th and 18th centuries, fled the plantations and created their own societies in the bush.

These Maroons, as they were called, were not unique to Jamaica. They sprang up throughout the New World, not only in the Caribbean, but in Central and South America, and in the United States as well; wherever there were slave plantations, there was resistance in the form of slave revolts and runaways. And wherever geography permitted, the escaped slaves gathered together in the hush to form communities. The most famous of these Maroon societies, Palmares in Brazil, contained upwards of 10,000 people and withstood almost a century of Portuguese expeditions against it before it was finally destroyed in the 1690’s. On a smaller scale, the southern United States was dotted with settlements of fugitive slaves who sought shelter in the mountains and swamps where they sometimes mixed with Indians. While most such communities were destroyed by the planter societies around them, in a number of cases the European powers could not overcome the Maroons and were forced to sign treaties with them; in Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Hispaniola, Mexico, Jamaica and Surinam, colonial governments offered terms to Maroons, recognizing their freedom and the territorial integrity of their settlements, But it is only in two areas, Jamaica and the Guianas, that the descendants of Maroons have continued as separate and distinct communities into the present. In Jamaica, descendants of the 17th and 18th century Maroons still live on the land their ancestors defended, ever conscious of their past as guerrilla fighters whom the British could not defeat.

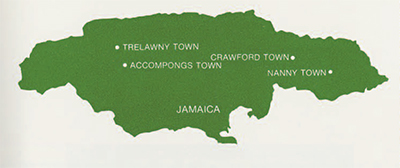

The Jamaican Maroons started with a small group of Spanish slaves who were left behind when the Spaniards gave up the island to the British in 1660. Their numbers were augmented by escapees from the new British plantations who either joined them or established their own settlements in the woods. By the early lath century there were some thousand fugitives living in the interior. Slaves escaped singly, in groups, or by the hundreds in bloody rebellions. Many must have died of wounds, starvation and exposure following their escape, but some did survive to forge new lives for themselves in the interior and to create new societies that were largely African derived. Initially, a number of small bands formed, but these eventually coalesced into two major groups, each comprising several villages. In the eastern end of the island, in the Blue Mountains and the intersecting John Crow Mountains, the Windward Maroons built their villages and planted their fields; in the western interior, on the edges of a jagged limestone formation called the Cockpit Country, the Leeward Maroons made their settlements. Both these areas are so inhospitable and inaccessible that they are even today largely uninhabited.

The Maroons were a thorn in the side of the British, whose plantations they raided for supplies, and whom they sometimes killed in the process. In addition, their presence in the interior was a challenge to British authority in the island, and encouraged plantation slaves to believe there was an alternative to the brutal hardship of plantation life, if only they could escape. Above all, the Whites feared that Maroon successes would stimulate what they dreaded most—an island-wide slave revolt. In the 1730’s, the activities of the Maroons increased sharply, and the Colonial Government shared with the Crown its fears:

“… we are not in a Condition to defend ourselves, the Terror of them [the Maroons] spreads itself everywhere and ye Ravages and Barbarities they commit have determined several Planters to abandon their Plantations, The Evil is Daily Increasing and their success has had such Influence on our other slaves that they are continually deserting to them in great Numbers and ye Insolent behavior of others gives us but too much cause to fear a General Desertion which without your Majesties’ gracious Aid and assistance must render us a Prey to them …”

The Crown might offer tax relief to help the island with the extra expenses incurred in trying to subdue the Maroons, but there remained the problem of who was to fight this formidable foe. In the absence of large numbers of troops from England, Jamaica had to fall back on its militia, and in a plantation society of masters and slaves, the raw materials for such a volunteer army were scarce. In the 1730’s, the island contained an estimated 80,000 slaves and 8000 Whites, of whom only 1000 were “masters of families or men of any property.” Most of the other Whites, aside from women and minors, were indentured servants. The colonial men of property, who had the greatest interest in routing the Maroons, were willing to serve as generals and colonels in the militia. but they had neither the inclination nor the numbers to fill out the ranks, Furthermore, they were needed at home to see to it that their slaves, who outnumbered the Whites ten to one, were not so encouraged by the Maroon successes that they tried to follow suit. The bulk of the White militia thus came from the island’s 1500 indentured servants, and they were often found lacking both in military skills and in willingness to risk death for their masters’ interests. The Whites that could be gathered for duty were not, in the opinion of a militia captain, the stuff of which soldiers are made. Captain Peters complained to Governor Hunter that instead of good shots, he had been sent “a parcel of Cowardly, Obstinate Fellows who neither good words nor bad will do any good.” But regardless of military quality, there simply were not enough White men to fight against the Maroons and hold the plantations at the same time.

Thus, the planters were forced to call upon their slaves and on the small number of free Blacks and Mulattoes to come to their aid, despite the uneasiness it caused them to arm the Blacks. Although they were less openly unwilling to fight than the Whites, the Blacks were scarcely more enthusiastic. Like the indentured servants, they had “no obligations either of honor or interest” to defend the planters’ property, and they were suspected of secretly aiding the Maroons. Slaves, if they distinguished themselves by extraordinary valor and service, might be given their freedom, but even in those very rare circumstances they had to continue fighting for the Whites. Rather than risk death for the planters’ cause, they often shrank from fighting, and sometimes deserted to join the Maroons. But despite the drawbacks in using them, free and slave Blacks comprised the majority of virtually every party sent out against the Maroons. In the 1730’s, in parties of some fifty to two hundred men, usually over half were armed Blacks, perhaps one-third armed Whites, and the remainder slave baggage carriers.

The parties the island raised against the Maroons not only failed to defeat them, they failed dismally. Their sheer incompetence in battle was encouraging to Maroons and plantation slaves alike. Frightened by their inability to contain the growing menace, the Colonial Assembly made desperate pleas to the Crown for trained troops. England sent soldiers to aid her prize colony, but they too proved of little use against the Maroons.

Fresh from Europe, the new troops were extremely vulnerable to the diseases of tropical Jamaica, including malaria and yellow fever. Local Whites who had already survived a period of seasoning fared better, as did the Blacks, many of whom had an inherited resistance to malaria. But the new troops were dying like flies. One of their commanders, Colonel Cornwallis, wrote home, “One Can’t Set 24 Hours without hearing of Some of the Corps being either Sick or Dead they say every body has a Seasoning and … that Seasoning has hitherto Carryed off every one that has had it . . .”

Weakened by disease, the troops were further demoralized and confused by the type of fighting they faced. They saw in it no opportunity for military honor, as they knew it. The Colonel continued, “I’m sure there is not an officer here but with Pleasure would go to the most desperate siege rather than Stay in this damned unwholesome place for then one should have a Chance to gain some Credit or die honourably, here no Reputation to be gained & no service to be done . . .”

To console themselves the troops, both officers and men, turned to drink. This further incapacitated them, for the drink was rum, “the ruin of this island” Governor Hunter called it, and “easier to came at here than small beer in England.”

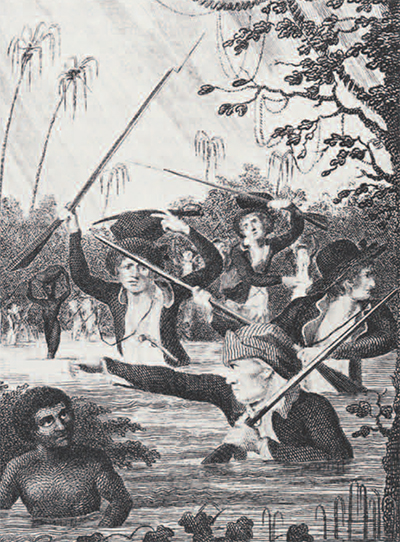

The nature of the warfare was so discouraging that it might have defeated a much more able and dedicated army. In the first place, getting men and supplies into enemy territory was a taxing exercise in its own right. The Maroons had purposely located their settlements in the most inaccessible areas of the island, and all movement had to be on foot, over difficult and dangerous terrain. And getting into Maroon country was less than half the battle—it did not even insure that one would meet up with the enemy. As Governor Trelawny tried to explain to those back in England in 1738. “The service here is not like that in Flanders or any part of Europe. Here the greatest difficulty is not to beat, but to see the enemy. The men are forced to march up the currents of rivers over steep mountains and precipices without a track, through such thick woods that they are obliged to cut their way almost every step … the underwoods being always full of saps and new shoots, exceedingly tough and bushy, twisted and entangled in a strange manner: add to this that they frequently meet with torrents caused by heavy piercing rains that often fall in the woods and against which tents are no shelter. In short nothing can be done in strict conformity to the usual military preparations and according to a regular manner, bush-fighting as they call it being a thing peculiar by itself.”

The river routes were said to be the easiest paths to follow, but the men traveling them found they might have to.. cross the Fords above twenty times in one day & near as often every day, which in most places is breast high, & … they often meet with high Rocks, to get over which; they were forced to climb on each other’s hacks, & to hand up their Arms Baggage, & Ammunition. . .”

These marches against the Maroons were called “the most laborious Service [that] can be well undertaken.” The best woodsmen could not march above five miles a day. By the time they got into Maroon country, they were fatigued with their March their Arms and Ammunition frequently Wett or Spoiled with their being obliged to lye nightly in those unsettled Woods, Exposed to the Rains and the usual excessive Foggs, …”

At best, when a party came upon the Maroons it was in poor condition to fight. At worst, the men could suffer all this and still fail to find the enemy. One expedition. sent out in 1730, got lost in the woods, and an estimated quarter of the men died from sickness and drowning in the rivers without their ever encountering a Maroon! The captain of this sorry expedition was court-martialled and shot.

A party led by Christopher Allen in 1732 had better luck. Allen led a group of men on a new route, over the highest mountains in f am aica, to the village of Nanny Town. By the time they sighted the village in a valley below them, they had been two weeks on the march, “Sick & lame, almost Starv’d.” Allen reported that their first thought was not how to attack the village, but “that we could get there to Dinner, at which we were all Overjoy’d.” But Allen’s men had to face a full day and night of fighting before they entered the village.

Allen’s party was indeed one of the fortunate ones in finding a Maroon village. Their settlements were generally so well hidden and defended that parties seldom got that far. The more usual contact the government forces had with Maroons was as victims of their ambushes. The mountainous terrain provided an ideal setting for a few armed Maroons to turn back an entire party. Troops fully expected that they would be ambushed sometime on their march up the narrow gullies and steep river beds, and in this they were seldom disappointed. As one neared the settlements, the ambushes became more numerous, and it was virtually out of the question to creep up to them unseen. Defenses increased and became more sophisticated and ingenious. The village of Quao, a headman of the Windward Maroons, “… was so situated … that NO BODY of men, or scarce an individual could approach it, that they would not have five or six hours notice, by their out centinals: … the only accessible way to it, was up a very narrow path in which holes were cut, from place to place, about four foot deep, all the way up, and down, with crutch sticks set before them, for the entrenched Negroes. to rest their guns upon …”

These Maroons, hidden behind hushes, were invisible to their attackers. Another common defense was to secure huge stones with props or ties and set them rolling down on the approaching troops.

Capturing a Maroon village was counted a major victory by the government, but the most it usually accomplished was to occupy the Maroons for a few months while they settled in a new location. Seldom were any great number of Maroons taken in battle. In one such “great success” the government took the village. but failed to capture, or even to see, a single Maroon, though they engaged in active fighting with them for an hour and a half! The Maroons set fire to a group of houses, and under cover of smoke the women and children fled to nearby caves that had been prepared as a place of refuge, while the men held the attention of the party. Then they too withdrew from the village. Troops occupying a Maroon settlement invariably destroyed whatever crops they could, which sometimes led to hardship and starvation for the Maroons. But when the rains threatened to cut the parties off from their own supplies of food and ammunition, they abandoned the settlements, and the Maroons sometimes reoccupied them.

The hardships of service in these parties were so great that many men forced to march against the Maroons escaped into the bush rather than face fighting them. Black defectors had the option of joining the “enemy”; the Whites could not join the Maroons, but they ran nevertheless. It was common for parties to lose several Whites by desertion in the first few days of their march, and in battle any number might run if they were not carefully watched. In one notorious case, a major expedition of two hundred seamen, specially borrowed from the navy, together with some hundred soldiers, turned back at the first cry of “Ambush ahead!” Then they fell to plundering and destroying their own supplies, the slave carriers having dropped them and run. They threw away the surgeon’s instruments and medicines, cast the meat and bread down a precipice, and to prevent any further advance by the party, broke open the ammunition boxes and scattered the powder and shot. Then, finding the rum, they drank all they could and marched home.

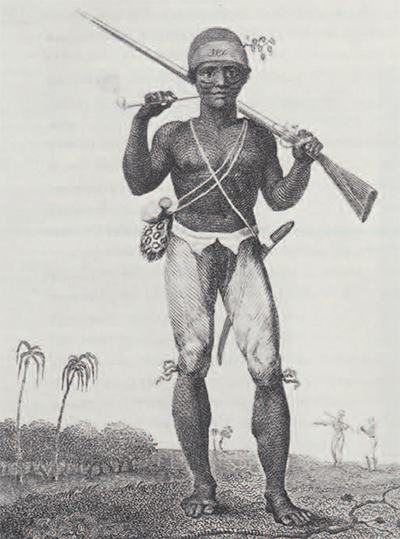

All this is not to say that some of the government forces, both Black and White, did not distinguish themselves in the service. A group of free Blacks, led by Sambo, were professionals at bush fighting, and a number of militia men and officers repeatedly showed valor on long marches and in battle. But for most of those sent against the Maroons the march was so exhausting, the battle so frightening, the successes so rare and the rewards so small that they pulled back whenever they could. The Maroons, on the other hand, were fighting for their very existence. and they brought to this fight all their energies and resourcefulness.

One measure of Maroon ingenuity was their ability to supply themselves with guns and ammunition from the plantation society, for the government made every effort to limit access to these dangerous goods. Maroons tried to carry off arms and ammunition whenever they raided settlements, and slaves who ran away to join them often stole arms from plantation stores. In addition, the government knew only too well how much of the party supplies found their way into Maroon hands, either carried there by Black deserters or left behind when the parties ran. The arms thus obtained would last indefinitely, given proper care, but the British were puzzled by the continuing supply of powder and shot until they learned from a captured Maroon of an ingenious method. Two captured White boys were made to write passes in the name of Colonel Needham, owner of a large plantation, for the ammunition. Maroons, pretending to be his men, would boldly enter Kingston and buy it from a merchant there. The Assembly passed laws forbidding such sales to Maroons, which suggests that at least several people were engaged in the trade, and that they might have been aware of their customers’ identity. The government also learned, after the fact, that the Maroons had bought powder and shot from an “Indian” who belonged to a sloop that stopped in the harbor. Men passing through the island probably asked few questions of potential customers. The captured Maroon also revealed that they had two hundred horns of powder, but were short of shot: they often fired their guns without shot to give the impression of firepower.

This was one of a number of psychological techniques the Maroons used to undermine the morale of the parties. Another trick they used to convince the enemy of their superior numbers and ferocity was to make as much noise as possible.

“When they Engaged they Constantly kept blowing Horns, Conch Shells, and other Instruments, which made a hideous and terrible noise among the Mountains in hopes of terrifying [the] Parties, by making them imagine their Number and Strength much greater than it really was.”

The Maroons seemed to enjoy taunting their attackers. Captain Lamb reported that the Maroons on top of a hill near their village “… Hallow’d to us to come up for they was ready for us and told us three times we came for to Fight ’em and runaway like a passell of White liver’d Sons of Bitches, …”

On another occasion they disconcerted the Whites by showing that they had advance knowledge of the government’s plan to have several parties converge on a Maroon settlement by different routes: a Maroon called out to admonish one party for arriving ahead of schedule since the party of free Blacks under Sambo was not due until the following day. Hidden in the bush, spying on the parties but invisible to them, the Maroons tried to entice the Black members to desert, “Inviting them by artful Expressions to quit a Slavish life.” One officer reported, “Several of them call’d to Captain Williams and it is suppos’d they are Party Negroes who have deserted, They call’d to our Negroes and Inquir’d after their Wives and acquaintance, and bid them tell them how well they live and if they will go to them they shall live so too, at the same time asking Our Party Negroes to come to them persuading them not to fight for the White Man …”

Maroons and Blacks in the parties also called out to each other in African languages, which must have made the Whites even more uneasy.

The Maroons were a society at war, and this fact was reflected in their social organization. The Leeward Maroons, under the leadership of their famous chieftain Cudjoe, had a sophisticated military organization. He “… Occasionally appointed as many as were necessary, of the Ablest under him as Captains & divided the rest into Companies, & gave each Captain, such a Number as he thought was proportionable to the merit he was possess’d of … The Chief Employment of these Captains was to Exercise their respective men in the Use of the Lance. & small arms after the manner of the Negroes on the Coast of Guinea, To Conduct the Bold & active in Robbing the Planta. of Slaves, Arms, Ammunition & ct. Hunting wild hogs, & to direct the rest with the Women in Planting Provisions—& Managing Domestic affairs.”

Cudjoe ruled with an iron hand, and promptly killed any man who disobeyed his orders or challenged his authority.

The Windward Maroons also subjected themselves to the severe discipline made necessary by the constant threat of battle. The head man at Nanny Town ordered the entire military operation, and anyone who committed a crime was shot to death. Here too, those men who were least noted for their courage worked with the women in raising provisions. The Nanny Town Maroons were well coordinated for fighting. A captured Maroon told of the way in which they prepared for the advance of troops toward their settlement: “… there were at Hobby’s [a plantation captured by the Maroons] 2 Gangs of Men 100 in each Gang & Several women which they had brought to help carry off the Spoil: . .. they left one Gang in the Negro Town to Guard the rest of the Women & Children; … they had determined on hearing the Partys coming to Ambush them in the River’s Course, that a Gang of 100 was to lay on Carrion Crow Hill & 100 more Hobby’s way, that a Drum was to be placed on the ridge over the Town to View the Partys and the Women in the town to burn the houses in case the Party should be too Strong, if not the three Gangs to Surround them on the beat of Drum, all under the Command of Scipio.”

In addition to their headmen, Maroons in both ends of the island relied on obeah men and women, that is, magical practitioners, for help in their battle for survival. One of them, Nanny, after whom Nanny Town was named, is still revered and remembered as a heroine for turning back the British fire by magic. Such supernatural aids may have given the Maroons a boost in confidence, but the bulk of their defense was provided by careful planning and ingenuity and a great deal of courage and resourcefulness.

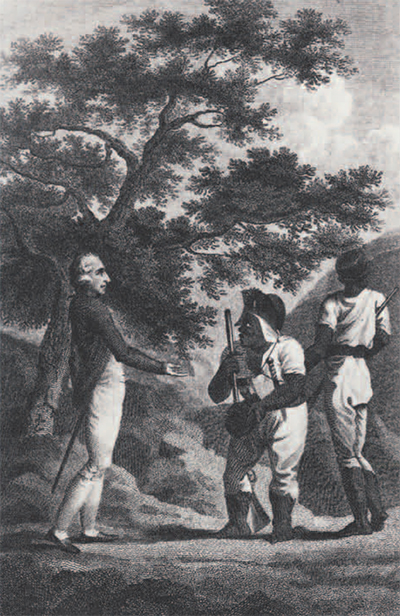

The Jamaican government had tried virtually every means of defeating its internal enemy—militia, regular troops from England, armed slaves and free Blacks, even imported Miskito Indians—and all proved unable to subdue the Maroons, There remained only one course open—to try to make peace with them. By the late 1730’s, Governor Trelawny was convinced that this was the only way out for the British, but for a White man to convince the Maroons that such a proposal was genuine was a major task in itself. One such envoy was turned back with a threat; another was killed, and his jawbone used to adorn the horn of a Maroon hornsman. Finally, in February of 1739, a militia party under John Guthrie succeeded in finding and capturing the settlement of Cudjoe, headman of the Leeward Maroons. The Maroons being thus at a disadvantage, Guthrie managed to press them for terms. Cudjoe and Guthrie signed a treaty and sealed the bargain by taking an oath together and drinking their own blood, mixed with rum, from a calabash. By the treaty, the Maroons were acknowledged as legally free, granted land reserves at the site of their villages, and allowed to engage in trade with the rest of the island. The integrity of Maroon society was recognized, their headman being responsible for all internal matters except the death penalty, which was reserved to the Crown. In return, the Maroons agreed not to harbor any future runaways in their midst and to help the government in bringing to terms other Maroons still at large. A few months later, a similar agreement was made with the Windward Maroons under Quao.

Thus came to an end, in 1739, an era of guerilla warfare in Jamaica. The Maroons had, by their persistent and courageous efforts, and their unconventional methods of fighting, defeated all British attempts to subdue them, and forced the recognition of their freedom, which was not accorded the slave population of Jamaica as a whole for another hundred years.

In 1795 the Maroons of Trelawny Town, the largest Maroon settlement in the island, rebelled and withdrew into the impenetrable cockpits, from which they were finally dislodged only with the aid of vicious hunting dogs. They were deported to Nova Scotia and finally Sierra Leone, and the controversy surrounding their deportation led Dallas to write his book, The History of the Maroons.