In April of 1974, just as the summer powwow dancing season was beginning, twenty-eight residents of central and western Oklahoma, including fourteen Indians, were arrested by agents of the U.S Fish and Wildlife Service for selling eagle and other migratory bird feathers. As reported by the Associated Press:

A widespread operation centered in Oklahoma is responsible for the slaughter of thousands of migratory birds for feathers which are sold as Indian artifacts, federal officials said Friday…the officials said federal agents, working under cover, had discovered the illegal trafficking in eagle and other migratory bird feathers and parts.

Museum Object Number(s): 97-84-1879

On April 5, 1974, The Daily Oklahoman published an interview with Henry Bushyhead, a widely respected Cheyenne craftsman who was charged with selling feathers of the scissor-tailed flycatcher (Muscivora fornicate) and the flicker (Colaptes cafer). Bushyhead stated:

I knew it was illegal to sell eagle feathers and I knew it was illegal to kill hawks. But, I didn’t know it was illegal to sell the feathers of birds beside the eagle. . . The white people want to put a ceiling on birds, but it’s a way of life with the Indian people. Why do you want to curb my way of life with your laws that I didn’t help write? I think we [Indians] deserve a little consideration. (Powell 1974:9)

The Bald Eagle Protection Act of 1940, amended in 1982 to include the golden eagle, makes it unlawful to “possess, sell, purchase, barter, offer to sell, purchase or barter, transport, export or import, at any time or in any manner any bald eagle commonly known as the American eagle or any golden eagle, alive or dead, or any part, nest, or egg thereof of the foregoing eagles” (16 USC 868). The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 provides similar protection to migratory birds (16 USC 703). (Additional protection to some migratory birds is found in the Endangered Species Act of 1973 [18 USC 1531].)

Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art, Tulsa, OK

The 1974 arrests were made under these laws. In the months that followed, each of the arrested Indians pled not guilty to the charges. None of the defendants was charged with killing birds, but only with having possession of eagle and migratory bird feathers and offering them for sale. No evidence was ever presented in court that any of the Indians were involved in the organized slaughter of birds. All but one, an elderly Cheyenne man, were found guilty and fined in the Federal Court for Western Oklahoma. All feathers and objects with feathers attached were confiscated.

News of the arrests and trials shocked Indian people throughout the United States. The federal protection of eagles was common knowledge, but few Indian people were aware that possession or selling of migratory bird feathers, other than eagle feathers, was against federal law. It was widely believed that the Indians of western Oklahoma were being politically targeted. If a precedent of successful prosecutions could be set in Oklahoma, a state with thirty-nine tribal governments and the largest population of Indians (over 252,000 in 1990), then nowhere in Indian Country could Indian people escape possible arrest for possession of feathers. Dance costumes were put away and feather fans and other sacred or ceremonial objects with feathers were hidden. The arrests were viewed not as an attempt to control trafficking in feathers, but as an attack by the United States Government on traditional Indian religious activities. This brought back the specter of forced assimilation experienced by Indian people in the last decades of the 19th century.

Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art, Tulsa, OK

The Religious Crimes Code

In 1882 Courts of Indian Offenses were established on reservations by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. A religious crimes code was among the listed offenses:

Any Indian who shall engage in the sun dance, scalp dance, or war dance, or any other similar feast, so called, shall be deemed guilty of an offense, and upon conviction thereof shall be punished for the first offense by the withholding of its [sic] rations for not exceeding ten days or by imprisonment for not exceeding ten days; and for any subsequent offense under this clause he shall be punished by withholding his rations for not less than ten nor more than thirty days, or by imprisonment for not less than ten nor more than thirty days. (Prucha 1973:302)

In a nation so proudly founded on religious freedom, it was legal to practice any religion except that of the first Americans. The Kiowa people in Oklahoma had experience with the enforcement of the religious crimes code when they began to perform a version of the Ghost Dance, known among the Kiowa people as the Feather dance because each of the dancers wore an eagle feather upright at the back of the head.

From 1890 through 1916 the Department of the Interior, Office of Indian Affairs, relentlessly tried to stamp out the “heathenish” dance, eventually withholding tribal rations and lease rentals from allotments until the Kiowas signed a statement forswearing the dance in 1916. Officially no Feather Dance has been held since then, for the Federal Government leased Ghattsa-Low’s land where the Feather Dance assembly took place. (Boyd 1981:98)

Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art, Tulsa, OK

Traditional Feather Use

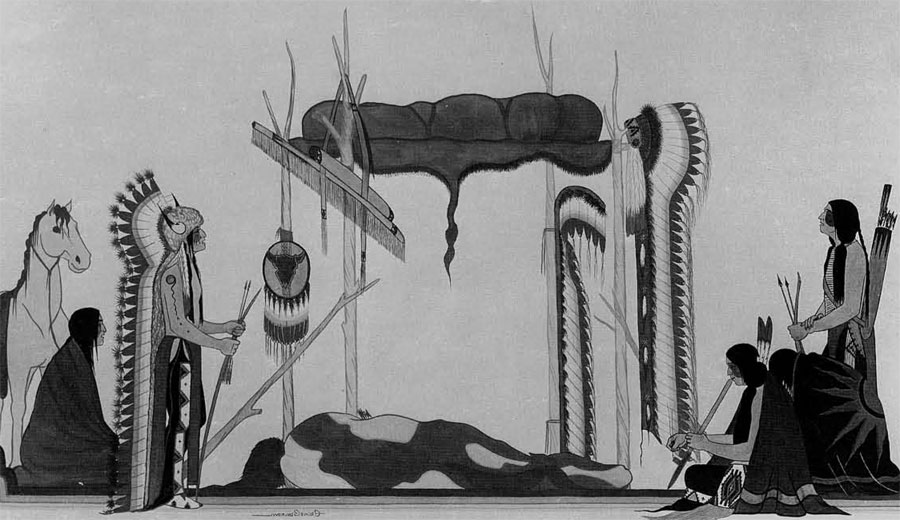

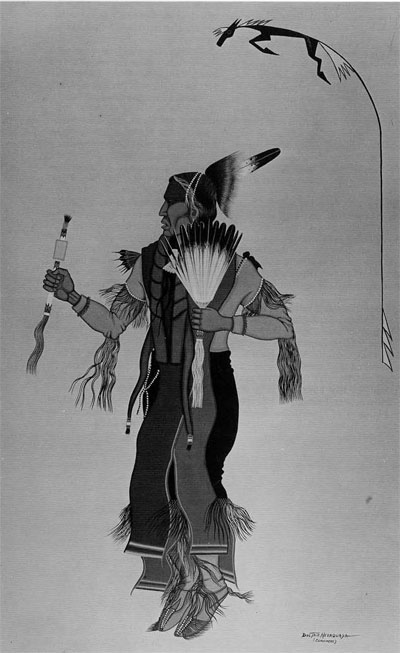

In order to gauge the impact of the 19th century religious crimes code and the 1974 arrests, it is important to understand elements of traditional Indian life. According to many Plains tribal traditions, feathers have been central to the religion of Indian people since the time of creation (Figs. 4,5). In a recent interview, Jerome Bushyhead (brother of Henry Bushyhead) explained the traditional Cheyenne belief in feathers.

The feathers are medicinal. They are part of the mystic, part of the traditions of the medicine of the Cheyenne because of his belief in the feathers. He believed in the feathers so strongly. He knew there was a supernatural power in them if he used them right. He liked to wear them. He fought to protect them. He used to pray with them, and to dance with them. So they were for medicinal purposes, strength, for spiritual being. They were an extension of your person.

An individual using feathers had access to the attributes of the specific bird (Figs. 6,7).

A shield adorned with the feathers of the eagle was believed to give its owner the swiftness and courage of that bird. If the feathers of the owl were tied on it, the man shared owl’s power to see in the dark, and to move silently and unnoticed.. . The feathers and heads of the sandhill crane were often attached to shields, for this bird possesses strong protective power and his voice is alarming to enemies. (Grinnell 1923:188, 195)

Museum Object Number(s): 97-84-1709.1 / 97-84-1709.2

Crow feathers were used by the Comanche as ghost medicine. They were placed near the door of the house to protect against ghosts. Crows and owls were believed to be natural enemies, and since both ghosts and owls were associated with the night, the crow feathers kept the ghosts away from the house.

Warriors also wore eagle feathers to signify war honors, as reported among the Ponca:

Eagle feathers alone are used.

Feathers set upright on the crown indicate Captors (in battle), one feather being worn for each capture. Feathers on the crown inclined (say 30 degrees or 40 degrees) toward the right indicate Scalpers, i.e., such a feather indicates that the wearer has taken one or more scalps.

Feathers set low on the head and inclined toward the left indicate Leaders, or men who have achieved power and control through prowess in battle or in marauding expeditions.

Feathers stripped nearly to the top (i.e., to the black tip) and then broken so that the tip may wave and flutter in the wind indicate Finders, or courageous and successful scouts and ready lieutenant who succeed in discovering many houses (i.e., enemies, the black tip symbolizing the smoke-blackened house-tops). Such feathers are commonly worn upright on the crown, but the meaning is the same when attached to the clothing or to the mane or tail of the horse.

Eagle down is worn by shamans to indicate mysterious power, or control by the Mysteries; it is considered to render the wearer alert and swift, and to make him invisible to enemies and invulnerable to arrow and tomahawk. Soft, floating or waving down is the symbol of the “ghost” or Mystery.

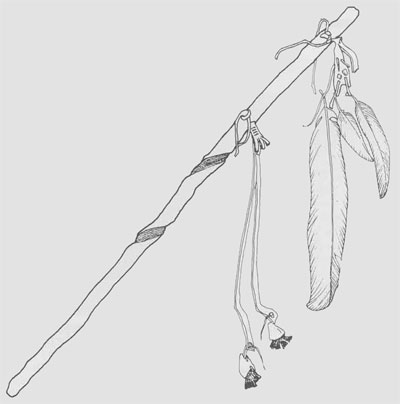

A baton or staff is carried by a man who has been wounded in battle, or who has made narrow escapes… A pendent feather attached to the baton signifies wounds. (McGee 1898:156-157)

Contemporary Feather Use

Although the context and content of Indian life in Oklahoma has changed dramatically in the 20th century, feather use has remained a basic ingredient in Indian life and religion. Today feathers are most widely used in the Native American Church and as elements of dance costumes seen at powwows.

Museum Object Number(s): 97-84-1874

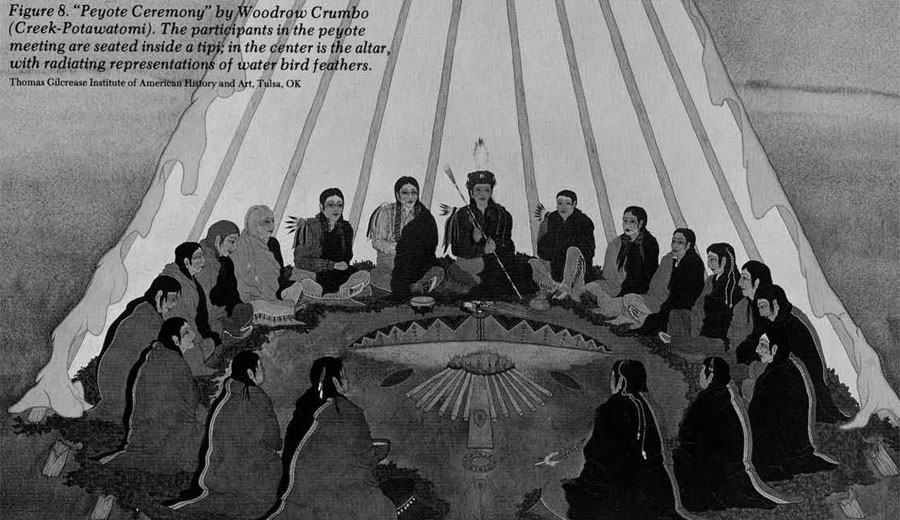

The Native American Church, also known among Indian people as the peyote church, diffused throughout the Plains tribes in the late 19th century as the traditional lifestyle was replaced by rations and reservations. The Church offered participants the opportunity to contact the supernatural through ritual and the ingestion of the peyote plant.

Under the mind-expanding effects of the peyote the celebrants feel the presence of the symbolic bird of peyotism, the “Messenger Bird.” For the Kiowas the bird traditionally depicted in their art is the Anhinga anhinga or cormorant, popularly known as the water turkey. But it could be an eagle, a scissor-tailed flycatcher, or a hawk. The bird is the messenger bird whose design the worshipers envision in] the smoke rising from the altar. The participants know the bird carries their prayers to the Spirit Power. The Kiowas prefer the cormorant because it is both strong and swift: strong enough to carry the heavy prayers of heartache and repentance, and swift enough to reach the outer limits of space where the mystery powers dwell. (Boyd 1981:107)

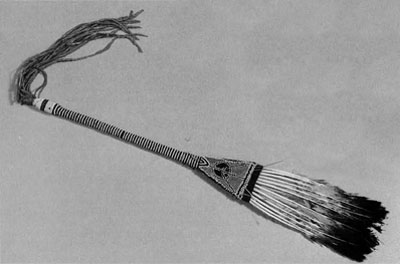

Meetings of the Native American Church are usually held on weekends or special occasions to celebrate birthdays, wedding anniversaries, or other significant events in the lives of the members. Each of the participants usually brings a peyote fan, or loose feather fan with a woven beadwork handle, to the Church meetings (Fig. 3). As mentioned above, the feathers of the anhinga, or water bird (water turkey), are frequently used because of the association with water which represents life (Fig. 8). Feathers of the yellow flicker (Colaptes auratus) are also used for ceremonial healing during Church meetings.

Museum Object Number(s): 97-84-1639

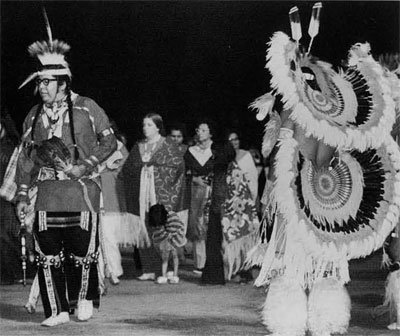

The use of feathers today is most visible at powwows. During the summer months, or the “pow-wow season,” most tribes in western Oklahoma sponsor intertribal powwows.

These gatherings are an opportunity for tribal members and their guests to camp together for several days, socialize, and conduct traditional activities. Other one-day powwows sponsored by Indian organizations, such as urban Indian clubs or Indian student associations in high schools and colleges, are held on weekends during the winter and spring months.

A major activity at each of these powwows is traditional dancing. Many pow-wows sponsor dance competitions where dancers from many tribes, drawn by the advertised prize money, are judged on both dancing ability and appearance. Today both men and women carry feather fans while dancing. Most popular are the rigid or flat fans usually made from eagle or hawk tail feathers with a woven beadwork handle. The peyote-style loose feather fans are also carried by a few dancers (Fig. 9). Eagle wing fans are also seen at powwows. The feathers of the red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) are favored by many dancers “because of their beauty and they soar so gracefully,” while children’s fans often are made with cooper’s hawk (Accipiter coo peril) feathers “because like children, the cooper’s hawk has an endless supply of energy and seems to have perpetual motion,” one maker of fans explained.

The most spectacular use of feathers today is in the dance bustles worn by “fancy dancers” or “feather dancers” (Fig. 10). This athletic style of “war dancing” developed in Oklahoma in the 1920s, probably among the Ponca, and has become a basic part of intertribal powwows. The early feather dancers wore feather arm bustles in addition to a feather back bustle. Today the arm bustles have disappeared, replaced by a shoulder bustle and a back bustle. This style of costume and dancing is descended from the “crow belt” worn by the Ponca during the Hethuska, or Omaha war dance. Although there is no specific tribal style in feather dancing, and both dance techniques and costume elements frequently change, the use of eagle feathers on the bustles still carries a religious meaning, as noted in a recent conversation with Jerome Bushybead.

When they use them they associate the Indian with the eagle, and they are part of him. That’s why they use them for the bustle sets. Also, it’s like an extension, he can be proud he wears the feathers to show how he feels about the bird. At the same time, the bird hopefully helps him to do the best he can when dancing (Fig. 3).

Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art, Tulsa, OK

One use of feathers that has changed in the 20th century is the wearing of an eagle plume at the back of the head by young women designated as tribal or powwow “princesses.” Don Patterson, a Tonkawa researcher who has studied feather use in Oklahoma, recently commented on this change.

There are now many new meanings. Take for example the eagle plume. There is a changing concept of utilization. Today you see them adorning princesses. This is contemporary. It is a 180 degree turn from the original usage. The plume belonged to the chiefs. Among the Tonkawa the hair ornament worn by men showed status. When it included a single plume, it belonged to a chief. Among the Tonkawa, feathers were not used as hair ornaments or on costumes. They were delegated to men only.

Feathers and the Law in the 1990s

Following the criticism from Indian people nationwide of the arrests in 1974, the Secretary of the Interior issued a policy statement which declared “the Department does not intend to seek legal action against Indian people who merely possess migratory bird or eagle feathers, or exchange them with other Indians without compensation” (Bellman 1974). Legislation that was promised by the members of the Oklahoma congressional delegation to clarify the rights of ownership of feathers by Indians for religious purposes did not materialize, however.

Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art, Tulsa OK

In August of 1978 Public Law 95341, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, became law.

Whereas such religious infringements result from the lack of knowledge or the insensitive and inflexible enforcement of Federal policies and regulations premised on a variety of laws. . . Whereas such laws at times prohibit the use and possession of sacred objects necessary to the exercise of religious rites and ceremonies; Whereas traditional American Indian ceremonies have been intruded upon, interfered with, and in a few instances banned: Now therefore be it Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled. That henceforth it shall be the policy of the United States to protect and preserve for American Indians their inherent right of freedom to believe, express, and exercise the traditional religions of the American Indian, Eskimo, Aleut, and Native Hawaiians, including but not limited to access to sites, use and possession of sacred objects, and the freedom to worship through ceremonials and traditional rites.

The religious crimes code of the late 19th century was finally laid to rest and Indian people could practice their traditional religions without hindrance. However, the ownership and use of religious articles with the feathers of eagles or other migratory birds remains ambiguous. Mere possession of such feathers is unlawful unless their ownership can be demonstrated to have preceded the dates of the federal laws or the eagle feathers were obtained under a permit from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (50 CFR 22.22). The application requires the identification of the religious ceremony, certification of enrollment in a tribe by a representative of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and certification by an authorized official of the religious group that the applicant is authorized to participate in the tribal ceremonies. A similar permit for religious use of migratory bird feathers is not available (50 CFR 21), and all wild birds found in Oklahoma, with the exception of the house sparrow and the starling, are protected. If feathers in dance costumes are replaced or new costumes or fans are constructed, the owner has technically violated the federal law unless the feathers are eagle feathers obtained by permit.

The policy of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service not to prosecute for mere possession of feathers remains in force. An Indian can transfer feathers to another Indian as a gift, but selling of feathers remains unlawful. An Indian artist can create fans or costumes using protected feathers and can be paid for the work, but not for the feathers. As tribes have developed tribal hunting codes for Indian lands, the treaty rights for hunting may exempt the taking of birds other than eagles for which the federal permit process exists. In Oklahoma, however, there are no legal means for procuring protected migratory bird feathers within the state.

Feathers remain an integral part of contemporary Indian religion in Oklahoma. Most Indians believe that their limited use of feathers does not threaten the continued existence of bird species within the region. What does threaten the birds is the continued widespread use of insecticides, the construction of powerlines, the clearing of nesting areas, and the slaughter of eagles by ranchers. Until the possession of feathers by Indians for religious purposes is no longer unlawful, true religious freedom remains denied for the first Americans.

It is difficult for non-Indians to understand and accept the fact that Indians do attach religious importance to the use of feathers in certain rites; indeed, they are essential if the rite is to have any religious meaning for the Indian. The religious needs of other, more orthodox faiths is [sic] readily accepted by most, but these same people reject as primitive the same needs of the Indians. The use of wine in the Catholic and Jewish faiths is not questioned as being used for bona fide religious purposes. In fact, during the prohibition era, a special exemption was created to allow for the procurement and use of wine for sacramental purposes. It is in this respect that Native Americans are asking for equal consideration of their own beliefs. For thousands of years, the natural wildlife. of this country have lived in no danger of extinction that could be blamed on the Indians. Yet, ironically, it is the Indian who is often accused of being insensitive to wildlife conservation, when all he is asking is simply that provisions be made so that he can continue to practice certain rites of his religion. (Native American Rights Fund 1979:5)