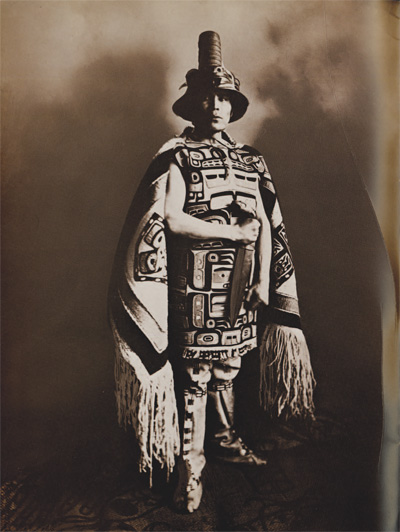

Formerly the Museum made a practice of having an American Indian as Assistant in the American Section. Dressed in his native costume, he appealed greatly to the school classes–especially to the younger grades, who listened to his talks on Indian life and customs more avidly than they would to any white teacher. At various times and for short periods the Museum had several of these, but the best known and the one of longest service was Louis Shotridge. Shotridge was on the staff of the Museum, as Assistant of Assistant Curator, for twenty years, from 1912 to 1932. Then, in the great financial depression that forced us to cut everything to the bone, he was one of the casualties.

Louis was a full-blood Chilkat Indian of the larger group known as Tlingit who inhabit the Pacific Coast of southern Alaska, the northernmost of the Northwest Coast tribes whos pictorial art and whose strange social and ceremonial organization based on prestige are famous. He was born in the native village of Klukwan. Here Dr. George B. Gordon, later Director of the Museum, met him on his visits to Alaska in 1905 and 1907 and was evidently greatly impressed by his personality, education, and culture. How he got them I don’t know, but he was evidently an outstanding man among his people. He was then (1907) a young man of twenty-four. Probably in the five years before he came to the Museum in 1912 he lived in the United States and became entirely accustomed to urban life. He told me once that he had been an opera singer, but of this phase of his life I knew nothing.

Louis was a big man physically, like most of the Northwest Coast Indians, upstanding, dignified, stolid, quiet, likeable. He came of a family of high rank in his community, his father being head chief of the Raven division of the Chilkat and master of the Whale House, and his mother being of the chief family of the Eagle division, a member of the Kaguantan clan and of the Finned House.

To understand the relationship, one must be familiar with the customs of exogamy and matrilineal descent, queer to us. The Chilkat were divided into two phratries, the Raven and the Eagle. One had to marry outside of his or her phratry and belonged to his mother’s group. So the children of an Eagle man were Ravens and were considered to belong to the same group as their mother’s brothers and sisters but not to their father’s; he, on the other hand, had more control over his sister’s children. Sometimes the father found his group in hostilities with that of his children.

So Louis was an Eagle of the Kaguantan clan. His first wife, Florence, was naturally a Raven, like his father. She died in Alaska in 1917 but, before this, had lived three years with Louis in Philadelphia where she was a great favorite with all, especially the children, being very intelligent, educated, and sweet. An article of hers, “The Life f a Chilkat Indian Girl,” was published in The Museum Journal in 1913.

As customary among Indians, Louis was given a single name at birth, Situwuka, or more phonetically, Stuwuqa. This, the name of several famous chiefs, very appropriately means “astute man.” “Shotridge” is a corruption or anglicization of the native name Tlothitckh. This was his grandfather’s name and descended to Louis after the former’s death; the meaning of the name is not recorded. It is said that the name “Louis” was given him by the first missionary to his people. who arrived there the day that Louis was born.

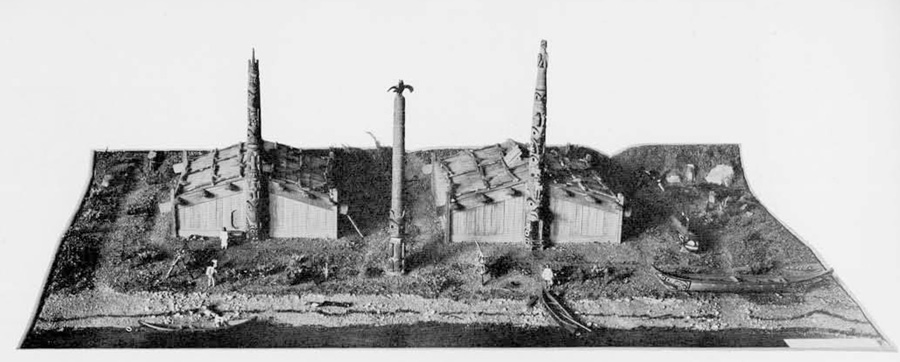

Apparently Shotridge’s first job in the Museum was to make a small-scale model of his native Chilkat village, Klukwan, This model, finished in 1913, was on exhibition for many years, but now, as it occupied much floor space, has been retired to storage. Although he had had no previous training in this art, he made an exquisite true-to-life model, with everything–houses, trees, boats, inhabitants–in perfect replica and to exact scale. Later he made another equally perfect but smaller model of a Haida Indian village with its totem poles; this is still on exhibition.

- (left) “Under-Sea Grizzly Bear Helmet” (right) “Killer-Whale Hat”

- “Murrelet Hat”

- “Wolf Helmet”

- (left) Painted basketry hat (right) Knife with wolf head

Soon Dr. Gordon realized the peculiar qualifications and advantages that Louis had for a museum. As a Tlingit Indian of high rank and family he had the entree to the best of circles, and was able to purchase some of the old clan ceremonial paraphernalia and regalia that were handed down from chief to chief and were zealously guarded in boxes, taken out only for ceremonies, and never seen by other collectors. In 1915 he was sent to Alaska for four years to secure such objects and the traditions and myths regarding them. He was much pained to see how much of the old Indian life had vanished since he had left there, the natives neglecting the old ways and ceremonies, and doing day labor in mines, canneries, and logging camps. He returned there again in 1922 for two more years, and apparently most of his time until his retirement was thus spent in Alaska with occasional short periods in Philadelphia.

On these expeditions he had a motorboat called the “Penn” on which he journeyed to the less accessible native villages, for all transportation in that region is by water; there were –and probably are–few and short roads. In addition to visiting his own people, the Tlingit, he made expeditions to the other Indian groups of very different languages, the Haida and the Tsimshian. Most of these expeditions were supported by the local merchant and member of the University Museum Board of Managers, John Wanamaker.

From them came the beautiful and extraordinary collection of ceremonial crests, each with its long history, which is one of this Museum’s most outstanding possessions, probably unmatched in quality elsewhere.

The ceremonial objects most prized by the Tlingit–as well as by museums and artists–are the clan hats and war helmets. Each belongs to a certain group, a division of a clan. and its nature is emblematic of that group. The house groups have a definite order of rank and the crests are considered community prosperity, though peculiarly the right of the leader of the house, from whom, at his death, they descend to his sister’s son. The major houses also had some crests of lesser rank that they had secured by various means. All of these were kept in chests, and shown or worn only at ceremonies. Shotridge distinguishes two classes of ceremonial headgear, clan hats and war helmets. The helmets, he says, “were ordinarily designed to represent the crests of the ancestors form whom the paternal grandfathers of the warriors who use them had descended.”

Most of the fine ceremonial Tlingit objects secured by Shotridge–most of the outstanding ones at least–have been described and figured by him in several articles in The Museum Journal, such as “The Emblems of the Tlingit Culture” (Vol. XIX, No.4). However, some excellent ones have never been published. For instance in his article “War Helmets and Clan Hats of the Tlingit Indians” (Vol.X, Nos. 1-2), he describes six hats of helmets and three ceremonial headdresses of which six are illustrated herein; he secured them from the leader of the Drum House at Klukwan in 1917.

The “Under-Sea Grizzly Bear Helmet” is the one worn by Shotridge in the accompanying picture of him in ceremonial costume. Of it he says that it was made for Daqutonk of the Kaguantan clan of Chilkat, the first successful leader of his house group, who also founded the Grizzly Bear House at Klukwan. It was originally claimed by the Tsimshian Tayquandi clan which was fast disappearing, and “had Daqutonk neglected t uphold this crest, it might have been completely lost, which would have been a disgrace for the other grandsons of Tayquandi.” It is of carved wood, painted green, red, and black. The eyes and a triangular nose-piece are of inset abalone shell. a pendent tongue of thin copper is attached, and strands of human hair are affixed above the ears. On top is a seven-element column of twined basketwork painted green.

The “Killer-Whale Hat” was mad for Gahi who succeeded Daqutonk, his maternal uncle. It was also originally claimed by a Tsimshian clan, but after they were defeated in war it was taken as spoil by their conquerors, the Naniyaaki clan, who employed it as an emblem of courage. This wooden hat is carved in the likeness of the animal and painted green, red, and black, with eyes and nostrils of inset abalone shell. A carved wooden upright crest, painted in the same colors, is fastened at the top, with human hair attached at the back; hair is also affixed at the back of the hat.

The “Murrelet Hat” belongs to the same group. The murrelet is the traditional crest of the Naysadi clan, to which Yikashaw, brother of Gahi, belonged. Yikashaw had it made for his personal use after he succeeded to the chieftainship on Gahi’s death. He built an annex to the Grizzly Bear House and called it the “Drum House.” Like the others, this hat is of wood, with low relief carved pictorial elements in stylized art, painted green, red, black, and white. Attached to the top is a carved bird, painted in the same colors, with an inset abalone shell, and with human hair affixed to the sides and back.

Some of the other fine ceremonial objects secured by Shotridge from his Tlingit tribsmen are, unfortunately, not accompanied by historical or mythological data–at least on the catalogue cards. The”Wolf Helmet” is a striking war helmet, large, and carved in the shape of a wolf’s head. It is more naturalistic than most crests, without the usual stylized low relief art, and is painted in bright colors, red, green, black, and white, with large eyes of abalone shell. The wooden ears are separately attached, and the sharp inset canine teeth are apparently carved of bone.

One of the largest ceremonial hats, nameless, twenty-four inches in diameter, is not of wood but of stiff but flexible twined basketry, painted with stylized pictorial designs in red, black, and green; these are now considerably faded. Attached to the top is a wooden crest representing a killer-whale fin painted red, green, and black, with eyes and teeth of abalone shell, and with a fringe of horsehair at the back.

The large knife that Shotridge is holding in his photograph was secured, probably with Louis’ help, by Dr. Gordon in 1905 at the time they first became acquainted. It is a beautiful example of Tlingit art and craftsmanship. The long, thin, sharp blade is copper, apparently hammered. The canine handle, probably representing a wolf, is naturalistically carved of horn, with lips, nose, eyebrows, and tongue of copper, fastened in by tiny rivets. The characteristic round eyes are of inset abalone shell. It is about twenty inches in length.

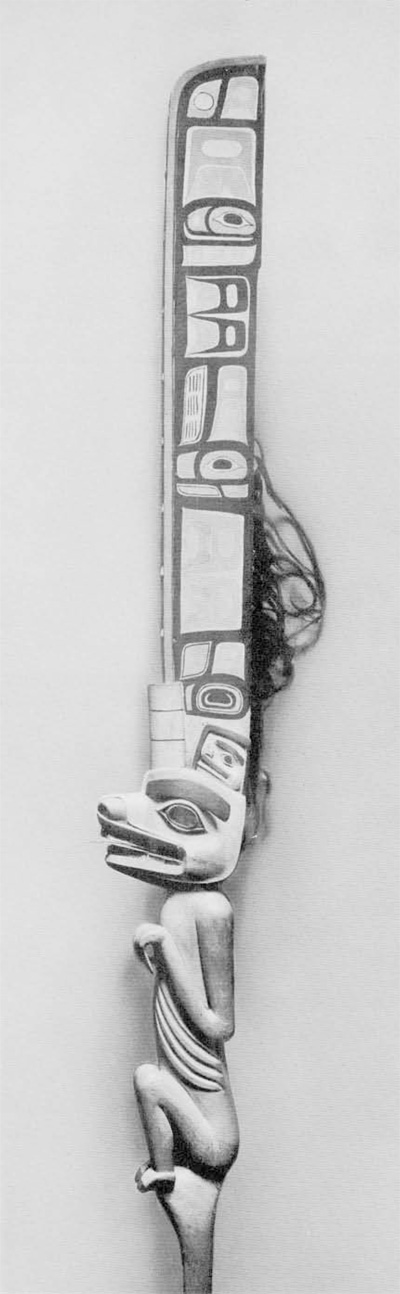

One of the loveliest of the many remarkable ceremonial objects secured by Shotridge is a dance baton over nine feet in length. This was carried by a precentor in leading the singing in ceremonial dances. Though the anthropomorphic body more resembles that of a bear cub, it is called the “Wolf Post” and is said to have been carved to represent the wolf emblem of the Shungukaedi group. The bright painted colors, as usual red, green, and black, betray little usage. Eyes, teeth, and nostrils are of inset abalone shell, and a copper tongue protrudes. Above the head is a wooden representation of the twined basketry column often found on helmets. The long “fin” is painted with stylized pictorial designs, pairs of small univalve marine shells are inset in the broader edge, and a fringe of human hair is attached to the thinner edge.

Although he published nothing himself beyond his articles in The Museum Journal, Shotridge helped a number of well-known anthropologists in their Tlingit researches, including, I think, both Dr. Franz Boas and Dr. Edward Sapir. He supplied the Tlingit information on which Dr. Theresa M. Durlach based her “The Relationship Systems of the Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian.” In the Museum’s collection of phonograph records there are a half dozen old wax cylinders of Tlingit ceremonial or mythological songs sung by him, presumably at the request of Dr. Sapir. He has also left us a large card file of data on the Tlingit under many headings, only a little of which has been published.

Poor Shotridge had a tragic end. He was in Alaska when his connection with the Museum was terminated and he apparently never returned to this country. He had become so accustomed to “civilized” life that he didn’t fit in there; he couldn’t do logging or can salmon, the main occupations of the deculturized Indian. Moreover, there was some bitter feeling towards him on the part of the Indians for having purchased and sent away some of the old ceremonial objects.

Such is, unfortunately, the lot of many Indians who return to the “reservation” after having been educated outside. Their training very often is useless there and life uncongenial. Their relatives reject them as neither white nor Indian, neither flesh nor fowl.

According to native report, Louis was building himself a small house alone in an unfrequented place. Some fatal accident occurred and he was not found until very much later. A number of years after his death, a letter from a Seattle bank came to my attention, addressed to him, and referring to the inactivity of his savings account for many years. I gave them all the information I could and I understand that his boy received a sizable sum thereby.

Photographed by: Reuben Goldberg