On June 2004, Harold Jacobs, the cultural resource specialist of the Central Council of Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska (CCTHITA), requested the loan of six objects from the Penn Museum for use in the Centennial Potlatch. The request was made on behalf of Andrew Gamble, the head of the Sitka Kaagwaantaan [Wolf] clan, who wished to commemorate the so-called Last Potlatch held in Sitka, Alaska, in 1904. The objects he requested were the Eagle hat, the Petrel hat, the Wolf hat, the Noble Killerwhale hat, the Shark helmet, and the Wolf baton, all of which had been collected for the Museum in the 1920s by Louis Shotridge. This was, in fact, the Central Council’s second such request. In November 2003, the Museum loaned the Raven-of-the-Roof hat to the Sitka L’uknax.ádi [Coho Salmon] clan for a memorial potlatch in honor of Sarah Davis James.

Because the Museum is committed to making its collections more accessible to Native American peoples, Museum Director Richard M. Leventhal enthusiastically encouraged us to pursue the project. We enlisted the help of our American Section colleagues, the Registrar’s officer, the Conservation department, and legal counsel. Unfortunately, two of the objects were too fragile (the Noble Killerwhale hat) or too large (the Wolf baton) to travel. But with the help of our colleagues, we arranged to hand-carry the four hats to Sitka.We purchased eight plane tickets—four for Museum staff members, ourselves plus William Wierzbowski (Assistant Keeper, American Section) and Stacey Espenlaub (NAGPRA Coordinator), and four for the hats themselves.

The Centennial Potlatch was held on October 23 and 24, 2004, at the Sheldon Jackson College Hames Physical Education Center in Sitka, Alaska. We arrived with Sue Thorsen, Curator at the Sitka National Historical Park (SNHP) at 11:45 a.m. on Saturday morning. Steve Henrickson, Curator at the Alaska State Museum (ASM), had just arrived on the ferry from Juneau and was unloading a truckload of objects. Host Kaagwaantaan clan members, their families, and Raven side guests, many of whom had flown in from neighboring communities, were starting to gather, greeting one another and bringing forth their clan regalia. Northern Tlingit society is divided into Eagle and Raven moieties, and each side is made up of numerous clan families. Mr. Gamble’s Kaagwaantaan clan belongs to the Eagle moiety and the Raven side guests included the Deisheetaan [Beaver], Kiks.ádi [Frog], L’uknax.ádi [Coho Salmon], and T’akdeintaan [Seagull] clans.

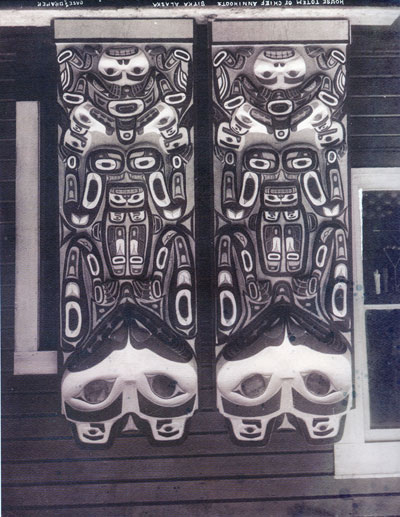

The gymnasium was transformed into a ceremonial space by the addition of monumental artwork originally dedicated at the 1904 potlatch. The Multiplying Wolf screen and poles from the SNHP and two Wolf house posts from the ASM were installed along the east wall. This created the backdrop for the Raven side dignitaries—24 male clan leaders who had come from the villages of Sitka, Angoon, Yakutat, and Hoonah. On the opposite side of the room, facing the Raven guests, was the Panting Wolf post and seating for 15 Kaagwaantaan host clan leaders. In front of the Raven guests and Kaagwaantaan clan seating areas were long tables used to display each side’s at.6ow (clan valuables depicting clan crests). At the foot of the Kaagwaantaan clan at.6ow table were photographs of clan leaders and other recently deceased individuals for whom no memorial potlatch had yet been held.

Between these two positions of honor was a central dance area flanked on either side by 5 long tables with 30 chairs and place settings for 300 Raven guests. The tables were decorated with white tablecloths and placemats that incorporated photographs of the hosts of the 1904 potlatch. Plastic utensils, soft drinks, candy, and chips were abundant, and pumpkins at the center of tables reflected the Halloween spirit. Other Kaagwaantaan clan members sat in the bleachers, as one of their tasks was to serve and support the Raven guests throughout the event. Finally, an exhibit of 30 photographs of the 1904 potlatch was set up at the south end of the room.

Potlatches

Potlatches are among the most distinctive cultural expressions of the Native American peoples of the Northwest Pacific Coasts of the United States and Canada. Practiced by communities as far north as the Ingalik of Central Alaska and as far south as the Makah of Washington State, they are perhaps best known among the Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Nootka, Salish, and Kwakwaka’wakw peoples. Potlatches are extravagant feasts where goods are given away or sometimes destroyed to enhance social prestige. The basic principle underlying the potlatch is reciprocity and balance as the host clan regales the clans from the opposite moiety with songs, dances, speeches, food, and gifts. Traditionally, they take place in very specific cultural contexts such as a memorial for a deceased relative, the rebuilding of a clan house, or the dedication of a totem pole.

Today, potlatches are also held for other reasons such as marking important anniversaries, graduations, and personal accomplishments. Among the Tlingit, however, the memorial potlatch (koo.éex’) remains the principal one. As Sergei Kan points out, they are not just about representing the social order; they also constitute key cultural values and principles of honor and mutual support. By hosting elaborate potlatches, individuals and clans maintain and gain status and recognition within the community. The potlatch is thus a complex and multi-layered communication system where participants express their relationships among themselves, with their ancestors, and with their future generations.

Although there is variation across communities, memorial potlatches are structured according to a standard protocol. They generally begin with the hosts welcoming the guests, and they quickly move into the mourning period where the hosts sing mourning songs. To alleviate their hosts’ grief, the guest clans immediately respond by singing songs, holding up their clan at.óow, and making consolation speeches. The potlatch then shifts to a more celebratory and joyous mood with dancing, the distribution of individual “fire dishes” of food for the ancestors,and the serving of a traditional meal. At this time, the hosts distribute food and small gifts and recognize individual guests with gifts of fruit baskets. Throughout this period the guests and family members give small amounts of money to members of the host clan with whom they have a special relationship. The hosts gather this money and announce each gift, and they then give new clan names to newborn children and individuals being adopted. Near the end of the potlatch, the hosts publicly recognize everyone who helped and supported them in their time of grief with a gift of money and sometimes a special gift such as a blanket. After all the money and gifts have been distributed, the guests generally perform a closing dance to thank the hosts.

The “Last Potlach” of 1904

At the turn of the 20th century, the Tlingit people experienced profound social changes. U.S. citizenship, social justice, and Christianity were topics of popular debate. Some clan chiefs and housemasters became convinced that the time had come for their people to abandon their old traditions and customs. In Sitka, the territorial capital of Alaska, 80 Christian Indians, many of them Presbyterians, formed an organization called the “New Covenant League” that eventually became the Alaska Native Brotherhood and Alaska Native Sisterhood. The league was committed to ending such customs as plural marriages, inter-clan indemnity claims, uncle-nephew inheritance laws, and potlatching. In 1902, several members approached Governor John G. Brady, a former Presbyterian missionary, and requested that he issue a proclamation that would “command all natives to changed and that if they did not they should be punished.”

Like other missionaries and government officials, Governor Brady considered the potlatch a practice that perpetuated prejudice, superstition, clan rivalry, and retarded progress. He was committed to breaking up the offensive clan system and replacing it with the independent family unit, but he was not eager to impose legal sanctions. Therefore, in a dramatic gesture, Brady decided to endorse one “last potlatch” at Sitka where Tlingit people from across southeast Alaska could gather and discuss their future. He appealed to the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, Ethan Allen Hitchcock, to secure the necessary funds with the justification that the event would “result in a lasting good to the people themselves and would save the United States many thousands of dollars in the way of criminal prosecution.”

One of the most prominent members of the New Covenant League was James Jackson (Anaaxoots), the head of the Kaagwaantaan clan. Other likely members were Augustus Bean (K’alyaan Eesh), Paddy Parker (Yaanaxnahoo), and Jacob Yarkon (Xeitxut’ch)—all high-ranking members of the Sitka Kaagwaantaan clan and part of the new vanguard of wealthy, educated Tlingit, who had been Brady’s allies and had served on the Indian Police Force. Obligated to host a major potlatch, but not wanting to jeopardize their good relations with Brady, they endorsed his last potlatch idea and agreed to serve as hosts.

The “last potlatch” was held on December 23, 1904, and lasted four weeks. It officially began with the grand arrival at Japonski Island (just south of Sitka) of the Raven side guests in traditional dugout canoes flying American flags. The Raven clans included the Deisheetaan of Angoon, the T’akdeintaan of Huna, and the Gaanaxteidí of Klukwan. The potlatch consisted of consecutive days of alternating feasts and dancing. The Kaagwaantaan clan hosts honored their guests with great quantities of food. According to the Daily Alaskan (Dec. 29, 1904),“Every morning and afternoon there is a great feast and only one article is served …. At the feasts the man or woman who can eat the most is regarded as the special hero of the occasion and he receives an extra allowance of the good things it is within the power of the hosts to bestow.”

The Kaagwaantaan clan hosts affirms their social status by dedicating five monumental wooden carvings. They dedicated the Multiplying Wolf screen and two house posts carved by Silver Jim (Kichxook) and installed them in James Jackson’s Wolf house. They installed two other Wolf posts carved by Rudolf Walton in Augustus Bean’s Eagle house. The Panting Wolf house post was raised up by pulleys and attached to the front of Jacob Yarkon’s World house. They publicly validated all these objects with proper Tlingit protocol. For example, the Daily Alaskan (Jan. 13, 1905) reported that Chilkoot Jack received $270 in cash, 100 blankets, 10 large boxes of provisions, and 7 coal oil cans filled with candlefish oil.

Governor Brady had hoped that his “last potlatch” would help end clan factionalism and further his assimilationist agenda. Ironically, it seems to have had the opposite effect. The Daily Alaskan (Dec. 29, 1904) observed that “one of the results of the potlatch has been to create enthusiasm among those Indians who still profess faith in the beliefs, superstitions, traditions and customs of the natives, as opposed to those who have forsaken them for the Christian faith.” Many of the traditionalists used the potlatch to educate the younger generation: “the old Indians who never took kindly to the white man’s religion are happy, and they are using the opportunity to impress upon the younger members of the tribe what they regard as the necessity of maintaining their old customs and traditions.”

Although they were sympathetic to some of Brady’s goals, it is clear that the Kaagwaantaan clan leaders did not support the end of potlatching. According to anthropologist Sergei Kan, unpublished records in Sitka’s Presbyterian archives indicate, for instance, that James Jackson continued to practice “the old customs” after 1904. Indeed, the Tlingit people never fully abandoned potlatching. Many communities continued the practice in secret or masked it by combining it with American holidays and social events. These covert strategies seem to have placated Governor Brady since potlatching was never outlawed, as it was in Canada. Today memorial potlatching is enjoying a strong resurgence, and the CCTHITA maintains a calendar of these events.

The Centennial Potlatch

The Centennial Potlatch began with welcome speeches by Andrew Gamble, who introduced his family and recounted his clan lineage. John Nielsen and Joe Bennett, Sr., as clan grandchildren, gave the opening remarks and announcements. This was followed by the repatriation of the Sea Monster hat, the singing of mourning songs, the Raven responses, the serving of the traditional meal, the feeding of the ancestors, the giving of small gift items, and distributing the fruit baskets. The first day ended at about 10 p.m. The second day began at noon with the entry and dancing of the Killer Whale clan, the veterans’ appreciation, the money collection, naming and adoptions, the installation of new housemasters, the hat dances, the blanket dances (yeikutee), the money distribution, and the return dance—ending about 4:30 a.m.

The Penn Museum objects were featured prominently throughout the Centennial. The eagle is the moiety crest of the Kaagwaantaan and an emblem of strength and vision. The right to use the eagle as a crest was granted to them by their Tsimshian neighbors. According to protocol, the Eagle hat (Ch’aak S’aaxw) was placed on the head of Andrew Gamble by Herman Davis (L’uknax.ádi) and Raymond Wilson (Kiks.ádi), members of the opposite Raven moiety during the mourning portion of the ceremony. On the second day, the Eagle hat was also danced alongside a copy made by Augustus Bean for the ASM. Harold Jacobs sang the Eagle hat song, which he had recently discovered in the archives of the Library of Congress.

The Petrel hat (Ganook S’aaxw) commemorates the story of Petrel and his rivalry with Raven and refers to his ability to control the weather, wind, fog, and rain. According to Harold Jacobs, it is one of the oldest clan hats in existence. Merle Enloe wore it during the mourning period. On the second day, Joe Howard, a Chookaneidí clan elder, danced the Petrel hat. His dance steps imitated the Petrel and wove in and around four stacks of blankets positioned between the Raven guests and Eagle hosts. Harold Jacobs sang a song to accompany this dance.

The wolf is the main crest of the Kaagwaantaan clan. According to Swanton, the clan received the right to use the crest after a hunter removed a bone from the teeth of a wolf. The wolf then appeared to him in a dream and made him lucky. Jerry Gamble, Andrew Gamble’s brother, wore the Wolf hat (Gooch S’aaxw) during the mourning period. On the second day Andrew Gamble also danced the Wolf hat alongside three other wolf hats as part of the blanket dances performed to entertain the Raven guests.

Because the Shark helmet (Toos’ Shadaa k’wat s’aaxw) had once been associated with death and bloodshed, the clan leaders decided that it should not be worn. Instead, Joe Bennett, Jr., carried the helmet during the mourning period, and it became the central focus during the veterans’ appreciation on the second day. Mr. Bennett invited all Tlingit veterans of war regardless of clan to come forward to be publicly recognized. In response, 30 veterans of World War II, Korea, Vietnam, Desert Storm, and Iraq created a large circle. Andrew Gamble’s niece, who is in active service, joined them as well. Joe Bennett and Paul M. Jackson, Sr., spoke eloquently about the fighting spirit of Tlingit warriors and their ability to look death in the eye and manage loss with strength and grace. Thus the Shark helmet became a symbol of honor and courage and served to unite generations of Tlingit people.

A number of other objects—some of which had been used in the 1904 potlatch—were loaned or made available by local museums and institutions. In addition to the Panting Wolf house post, the two Multiplying Wolf house posts, and the Multiplying Wolf house screen, the SNHP provided the Eagle Nest house drum, the Wolf house drum, and the Eagle Nest bent-wood box which they store for Andrew Gamble, the Killer Whale hat, the Beaded Killer Whale robe, and the Killer Whale dagger stored for Mark Jacobs, Jr., of the Dakl’aweidf clan, the Mary Willard Killer Whale robe stored for Georgina Dapcevich, Dakl’aweidf, and the Wolf Tracks robe, the High Caste button robe, and the Wolf hat stored for Harold Jacobs, Yanyeidf. The SNHP also made Raven side objects available to participating Kiks.ádi clan leaders, including the Peace hat stored for Fred Hope and the Frog hat and K’alyaan hammer stored for Ray Wilson. In addition, the SNHP made two National Park Service-owned objects available to the host side including the Chief Johnson Killer Whale robe and the Thunderbird Chilkat robe. The ASM loaned eleven objects, including two Wolf house posts, an Eagle hat, a bear hat, two spruce root hats, a Chilkat tunic, two canoe prows, a wolf robe of cloth and hide, and a contemporary raven’s tail robe.

Today there are only three extant Kaagwaantaan clan houses in Sitka—the Bear house, Eagle house, and World (or Noble) house. An important part of the Centennial was the reinvigoration of the 18 clan houses present in 1904: the Rock house, Star house, Eagle’s Claw house, Halibut house, On the Water house, Two Door House, Grizzly Bear house, Wolf house, Eagle house, Noble house, Burnt Down house, Eagle’s Nest house, Below house, Shark house, Box house, Looking on the Sea house, Standing Sideways house, and Salmon Frame house. Some of these houses have multiple names.

According to Mr. Gamble, the original houses were to have “air breathed back into them.” This took place after the adoption and naming part of the ceremony when 18 male clan members, each with the appropriate lineage, were given the names of the 1904 housemasters. Money was placed on each individual’s forehead and the name was announced and repeated three times by the audience. Names in Tlingit culture are a form of clan, and sometimes house, at.óow and they often carry with them social obligations, histories, and even specific practices. In this way, the names of the four house‑masters who hosted the 1904 potlatch were recognized and passed on to their current incarnations. Andrew Gamble was reconfirmed as Anaaxoots, the head of Wolf house. Ken Johnson was named K’alyaan Eesh as head of Eagle house. Merle Enloe, Jr., was named Xeitxut’ch as head of High-caste house. Karl Greenwalt, Jr. was named Yaanaxnahoo as head of Bear house.

The other newly installed housemasters were as follows. M. O. Brown, Jr., was named Yantan as head of Star house. Larry James was named Kaalghaas as head of Eagle’s Claw house. Judson Thomas was named T’aawyaat as head of Halibut house. Chester Jackson was named Kaawak’nuk as head of On the Water house. Sam Wanamaker was named K’anaaneik as head of Two Door house. Jack Williams was named Aandeishi as head of Burnt Down house. William Kanosh, Sr., was named Taashee Eesh as head of Eagle’s Nest house. George Nelson, Jr., was named Kaajixdaakeenaa as head of Below house. Reggie Nelson, Sr., Kooxich, was named head of Shark house. Charles Paddock was named Yanjiyeetgaax as head of Box house. Paul Edwards was named Kaatshi as head of Standing Sideways house. Thomas Young, Jr., was named Khuchein as head of Box House Child house. Due to health reasons, not all of the 18 men were present. They were confirmed in absentia with another housemaster standing in for them.

Celebrating Tlingit Culture

The Centennial Potlatch is part of the broader contemporary movement by the Tlingit people to invigorate their clan histories and traditions. The four Penn hats, along with the other objects made available and/or repatriated by museums, provide a tangible material connection between 1904 and 2004. They reveal the power of things to establish connections across time and space. These connections were given social form through the naming and installation of the 18 Kaagwaantaan housemasters. Because the installation was witnessed by the Raven moiety clans, it carries a series of social obligations, responsibilities, and expectations. The Kaagwaantaan will, in turn, participate in future potlatches honoring their opposites.

Finally, the Centennial Potlatch did not slavishly imitate the potlatch held a century earlier. The Tlingit people are not seeking to recapture some Golden Age. Indeed, Governor Brady’s aim was to end “the old customs” and facilitate progress. The failure of his potlatch policy is testimony to the enduring strength of the Tlingit people and the continued vitality of their culture in a modern world. In recognition of this, Alaska’s current Governor, Frank H. Murkowski, proclaimed October 23 and 24, 2004, as “days of celebrating Tlingit Culture in honor of the so-called ‘Last Potlatch’ of 1904.” The proclamation acknowledged that “attempts at extinguishing Native culture have failed” and that “the value of such culture and cultural diversity is now known and accepted for the benefit of all.”

Hinkley, Ted C. The Canoe Rocks: Alaska’s Tlingit and the Euroamerican Frontier, 1800–1912. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1996.

Kan, Sergei. Symbolic Immortality: The Tlingit Potlatch of the Nineteenth Century. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989.

Kan, Sergei. Memory Eternal: Tlingit Culture and Russian Orthodox Christianity through Two Centuries. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 1999.

Swanton, John R. “Tlingit Myths and Texts.” Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 39. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1909.

White, Lily, and Paul White. “Koo.éex’: The Tlingit Memorial Party.” In Celebration 2000, edited by Susan W. Fair and Rosita World, pp. 133-36. Juneau, AK: Sealaska Heritage Foundation, 2000.