Gilgamesh, the king of Uruk (modern Warka in southern Iraq), was on his way to the place where a couch had been prepared for the “sacred marriage” between him and the goddess Ishhara. When he approached the place where this wedding was to be performed, Enkidu, who had been sent into Uruk to compete with Gilgamesh, stood in the street to bar the way. Gilgamesh and Enkidu began to wrestle.

This episode is preserved in the Old Babylonian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh (ca. 1700 B.C.E., the original is housed in The University Museum):

Enkidu barred the

gate with his foot,

they seized each other,

they bent down like

expert (wrestlers),

they destroyed the

doorpost, the wall

shook.

Gilgamesh and Enkidu

were holding each

other,

like expert (wrestlers)

they bent down,

they destroyed the

doorpost, the wallshook.

Gilgamesh bent (his one knee),

with the (other) foot on the

ground.

(col. iv 12ff.)

The last two lines of this passage describe the position of the victorious wrestler who has succeeded in lifting his opponent from the ground, holding him by his girdle over his head while bending his own knee.

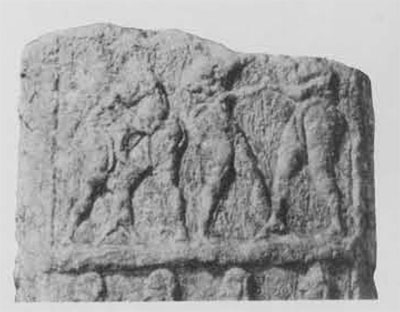

The “heroes” depicted on Near Eastern seals frequently wear girdles, even when they are otherwise unclad. I refer the reader to a well-known statuette from Khafaji dating to about 2600 B.C.E. where each wrestler is gripping the girdle of the other (Fig. 1; Speiser 1937, Fig. 4). From roughly the same period is a fragment of a stela on which we find the oldest representation of wrestlers (Fig. 3). Both these examples indicate that the Mesopotamians practiced belt wrestling. On some seals we see the victorious hero with a bent knee, holding a lion over his head. Even if the hero was wrestling with a hull, that animal was wearing a belt (as did the hero) that the wrestler grasped (see Gordon 1939: 5). The passage in the Old Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh has to be interpreted as representing belt wrestling: the victorious wrestler bent one knee on the ground and lifted his adversary. over his head (even if it is not explicitly said in the text).

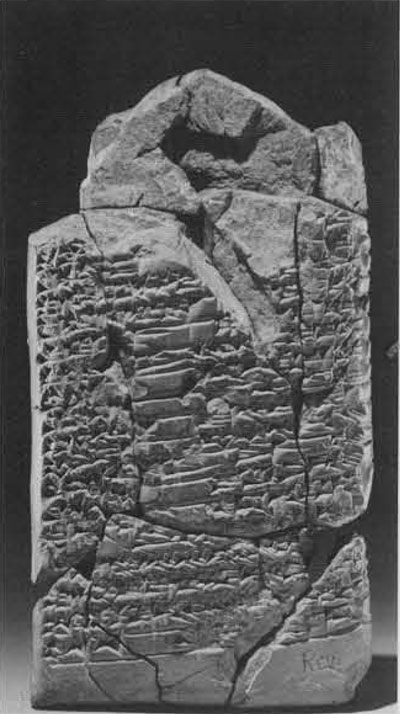

Let us now deal with another test from the Old Babylonian period; written in Sumerian, concerning the marriage of Mardu (CBS 14061, copied in Chicra as no. 58; original in The University Museum). (Mardu was a west Semitic god, brought into ‘Mesopotamia by the invading Amorites from the west.) Mardu is unmarried and he asks his mother to obtain a wife for him. Her advice is: “Take a wife wheresoever you raise (your) eyes, take a wife wheresoever your heart leads you!” A feast is celebrated in Ninab to which Mardu invites the god Numushda his wife, and his beautiful (laughter named Adgarkidug. During this festival, athletic games took place in the great courtyard of the temple. In these games Mardu not only defeats his adversaries but also kills them. Numushda, who rejoices at Mardu’s strength, oilers him silver and precious stones which Mardu, however, refuses to accept. He wants Adgarkidug and Numushda gives her to Mardu as wife. The passages from the Old Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh and the marriage of Mardu might point to an old custom of arranging athletics and trials of strength as a part of preparations for a wedding.

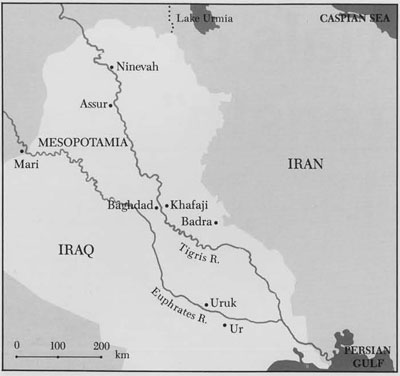

Shulgi, the second king of the famous dynasty of Ur (a Sumerian site in modern-day Iraq) who reigned from 2094-2047 B.C.E., was a man who was accomplished in all kinds of intellectual, cultic, and military activities, and certainly also skilled in athletics (see Fig. 4).

“In trials of strength and athletics I am (foremost),

in the great courtyard, as on the battlefield, who can oppose me?

I am the one who is strongest and most skilled in athletics and trials of strength.” (Shulgi Hymn C, lines 131ff)

Here, the great courtyard of the temple is the site of athletic events as it was in the marriage of Mardu text and in the literary composition we call “Curse of the City of Agade”: ‘like an athlete coming into the great courtyard” (line 102).

Wrestlers also occur in an Old Babylonian letter found at Mari. King Samsi-Addu sends a letter to his son Jasmah-Addu, king of Mari, complaining about the way he directs the war against his enemies: “You and the enemy continually devise stratagems for killing each other just like wrestlers, one seeking stratagems against the other” (Dossin 1967: No. 5, lines 7-9). A legal text from about 2000 B.C.E. mentions wrestling: “Mr. Guzani has killed Mr. Kali; Guzani was questioned; (he said:) ‘he has before (the killing) beaten me in wrestling’ ” (Falkenstein 1956: No. 202, lines 15-18). Guzani was a had loser, and before the killing, the two men had been quarreling.

Athletics are also known from post-Old Babylonian texts. One text, found in Assur (the capital of Assyria until about the 9th century), dating to about 1200 B.C.E. (the source text goes back to Old Babylonian tims) mentions athletics in connection with a temple festival; the people play drums and cymbals, they slaughter sheep, and at this gathering of people,’ “young men, the athletes [literally, the strong ones], fight one another in trials of strength and athletics before you (a deity)” (see Lambert 1960:116ff.). A text from Kuyunjik (the Old Niniveh, the capital of’ the late Assyrian Empire) mentions athletes performing at the festival of a goddess.

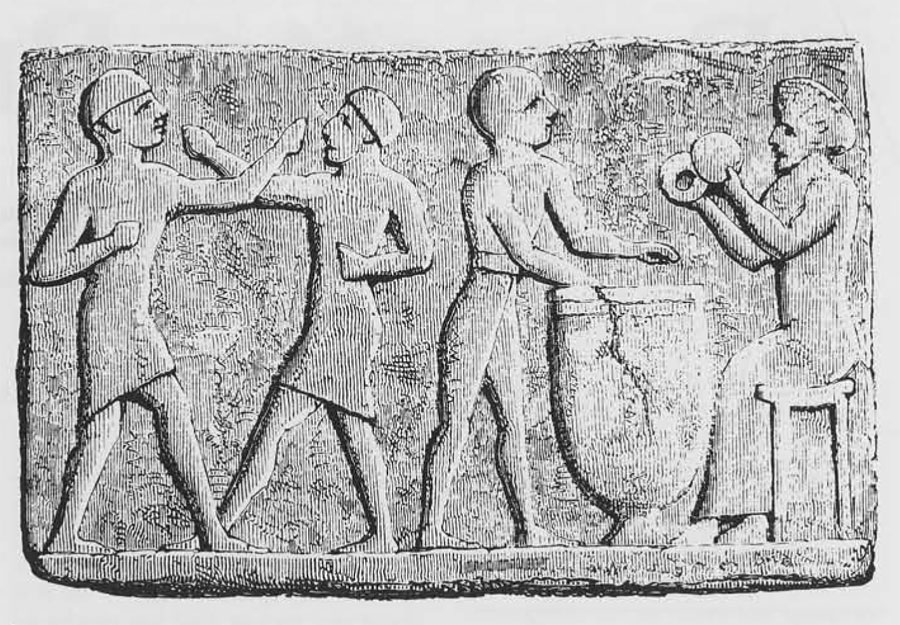

The Assur text has its counterpart in a relief (see Meissner 1920:420) on which two men are boxing(?) and two playing drum and cymbal, evidently referring to performances at a temple festival (Fig. 5). There is an interesting reference to organized athletic events in an astrological text from Assur: “in the Month of Gilgamesh kw nine days men contest in wrestling and athletics in their city quarters” (Reiner 1981:81, lines 13-15). Finally, an incantation text (from the first millenium B.C.E.) has the following admonition. “Place (two figurines) of bitumen (representing) two grappling wrestlers (for magical use)” (Nies and Keiser 1920: No. 22, lines 172-173.

As we have seen above, wrestling is mentioned in an Ur III legal document. A very few economic-administrative texts from the same period contain references to athletes. One text (Legrain 1937-1947: No. 1137, line 2) mentions beer as a ration for athletes; two other texts (ibid, Nos. 189 reverse, lines 3-4 and No. 191 reverse, lines 8-9) mention lambs and flour as food delivered to the “house of’ the athletes.” These neo-Sumerian documents show that athletes were an organized group, supported and run by the state or temple.