Sometime in the second decade of this century, the Misses Elizabeth H. and Sarah L. Metcalf made their way through Northern Luzon in the Philippine Islands picking up samples of the clothing, household possessions, weapons, and tools used by the native tribes. Among the headaxes, lime tubes, tobacco pipes, chicken baskets, and fish traps which the Metcalf sisters brought back to the United States were ninety-seven hats ranging from a carved wooden helmet with a stylized face and eyes of yellow glass to cartwheels big as bumbershoots. These hats are now in the University Museum where, along with examples of headgear from other islands, they make up a representative collection of hats from the Philippines.

At the time the hats illustrated on these pages were assembled, it was still possible to determine by its shape, material, construction, and decoration approximately where each hat had been made. A hat not only revealed something about the man who wore it, but also reflected borrowings from the streams of culture that for centuries had flowed into the Philippines.

The Philippine Islands have long been subject to influences from both East and West. The Greeks knew about these islands; Ptolemy, writing in the second century B.C., mentioned Leyte and Mindoro. Since the Philippines occupy a key spot on the migration routes from Southeast Asia into the Pacific, they were easily reached by sailing ships. Influences from India began to reach the archipelago perhaps as much as 1500 to 2000 years ago, and there is evidence that Hinduized Malays from the Javanese empire of Majapahit may have tried to colonize some of the islands.

Long before Caoh Ju-Ka, the thirteenth century Chinese geographer, visited the Philippines, traders from Southern China had established small settlements on Northern Luzon. Mohammedans from Borneo and the Moluccas dotted the coasts of Mindanao with villages in the fourteenth century, and Japanese travelers criss-crossed Luzon in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries searching for ancient Chinese jars.

Magellan sailed into Cebu Island in 1521 to claim the Philippines for Spain, but it was not until four decades later that the Spaniards, using the slogan of Predicar, Pacificar, y Poblar, began their conquest of the islands. From that time until 1898, when the United States took over the administration of the Philippines as part of the Spanish-American War settlement, Spanish priests and soldiers spread Iberian ideas and customs throughout the archipelago.

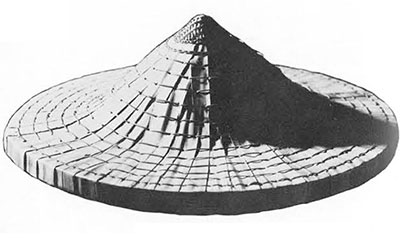

A Spanish painting dated 1564, entitled “The Landing of the Spanish in the Philippines,” shows three natives wearing headgear. The styles they wore–a pointed palm leaf hat, a head band with carabao horns attached, and a Moro-inspired basketwork hat–were still being worn in the 1900’s. Spanish writers, reporting on life in Luzon in 1570, said that lowland men wore cloth potongs and the women had headbands made of human hair.

That foreign fashions appealed to native taste was soon apparent to the Spaniards and they quickly wrote home for brightly colored hats to use in trade. Spanish styles spread rapidly. By the 1660’s, the lowlanders of Luzon–the Tagalogs, Cagayans, and Ilokoans–had shoes on their feet, jackets on their backs, and hats on their heads. The cloth potong shared the fashion spotlight with head coverings woven from such wild vegetable material as rattan, the stems of the nito fern, and bamboo.

One of the principal functions of clothing is status identification. It is not surprising that when de Morgan’s book about the Philippines was published in 1609, he mentioned that one could tell the social standing of a Philippine coastal dweller by looking at his potong. The potong, a headcloth which could be twisted like a turban or folded on the head like the crown of a hat, revealed a man’s record in life and his rank in society. Only a man who had killed another might wear a red potong, and seven souls must have fallen beneath his headaxe before he was entitled to a headcloth with crowns embroidered on its borders.

In Luzon, where most of the hats in the Museum collection were gathered, much of the population had come under the influence of Christianity. But in the steep rugged mountains of the North lived hard-to-reach pagan tribes that retained their individuality. When the United States Army came in, they were still cutting off the heads of their foes, and in habits and in dress they differed sharply form the Christianized tribes of the coast.

The sun and rain hat worn by both men and women who work in the rice and camote fields has a pan-Philippine distribution, but other pagan and Christian styles are distinct. Both in form and function they reflect in part the history of contact. Christian women as well as men put hats on their heads. Only men wear hats in the pagan villages. Most pagan women usually confine their hair with beads, putting on hats only when they work in the fields.

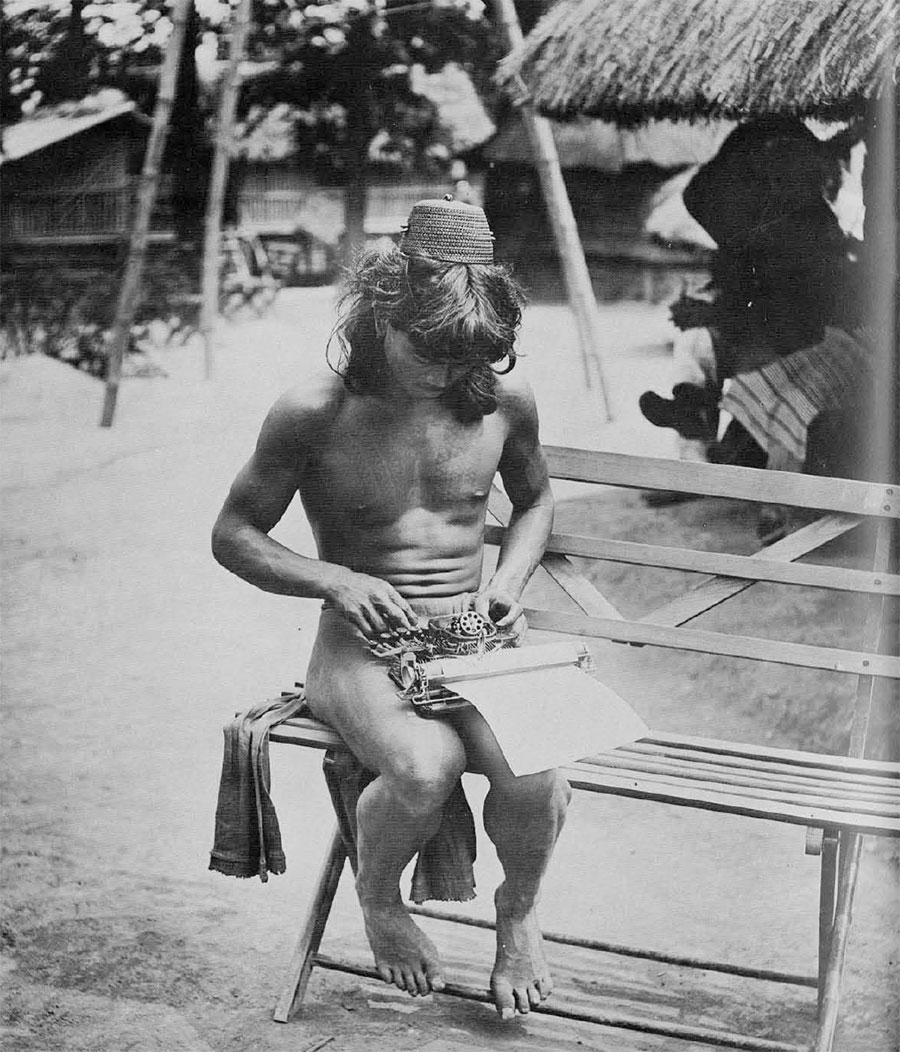

A.E. Jenks, the ethnographer who studied the pagan Bontocs of the Mountain Province at the turn of the century, correlated the wearing of hats with hair styles. Those men who cut their hair short wore headcloths and carried their tobacco in bags or baskets, while long-haired men wore basketwork caps and stuffed their smoking equipment into their hats.

Museum Object Number(s): 50-49-433

Museum Object Number(s): 50-49-1800 / 50-49-1135 / 50-49-441

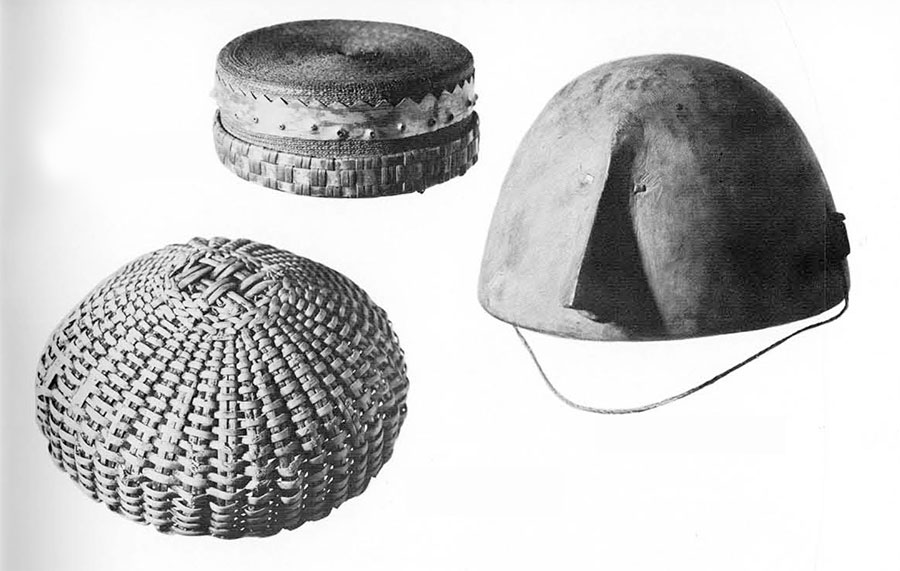

Among the pagans who wear hats, the Bontoc Igorot and Kalinga have basketwork suklangs and the Bontoc and Ifugao wear wooden helmets. The Tinguian, a tribe living next door to the Christians of Ilocos Sur Province, put on round cone-shaped bamboo hats or hats made from gourds or wood.

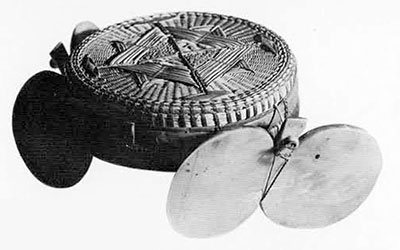

The basketwork suklang of the Kalinga and Bontoc was not just a flattish hat the size of a flapjack perched on the back of a man’s head. It was an effective carrying device for tobacco, flint, and tinder, and it held in its crown such small stuff as a man might need during the day.

The chain or cord which fastened the hat across the forehead also held a tobacco pipe, freeing both of a man’s hands for work. At the same time the suklang was a passport–a document of passage– that told strangers at a glance whether the traveler was friend or foe, eligible as a suitor or already married, an established hunter of men or one whose success in life was yet to come.

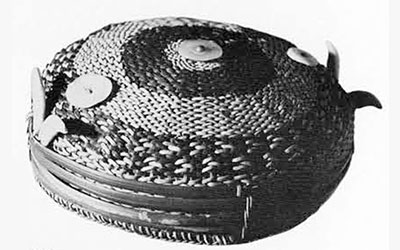

There are five styles of Bontoc hats in the Museum collection: a sleeping hat, a small fez, a shallow soup-bowl style, a pillbox, and a carved wooden helmet. Both men and women slept in the kut-lao, a close-fitting, round, wickerwork hat of natural rattan which had a hold in the top and was often held on by a cord from which dangled beads in blue, red, or crystal. Sleeping hats accompanied unmarried men and women to the grave.

At the age of six or seven, a Bontoc lad put on his sulpak, the small bowl-shaped hat or flattened pillbox, which by its appendages and decorations recorded his progress through society. When he was old enough to go head-hunting, the girls in the ulogs (dormitories for maidens) gave him dogs’ teeth and boars’ tusks to stick on the sides of his hat. He sewed slabs of pearl shell on the sides of covered the top with agate beads and added bunches of feathers on special occasions. Traditionally there were from one to three mother-of-pearl buttons on the crown of the bowl-shaped hat, and tufts of animal hair stuck up at each side over the three or four turns of red-dyed rattan which trimmed the edge. But when a man married, he put on a sober, less fancy hat; only bachelors or men between wives wore gaudy headgear.

The fez or ti-no-od worn in Bontoc and Samoki had a heavy twist of brass on its dimpled top, and similar brass pieces adorned either side. Both the Bontoc and the Ifugao, a tribe famous for its carving, wore wooden helmets. Some helmets were plain and round as a split coconut, but others were carved caricatures of human faces with long beaky noses, squinty eyes and tiny pursed mouths. Others had tonsured crowns like those of sixteenth century Japanese traders.

In shape and ornamentation the Kalinga pillbox evokes memories of the Moors. There is an Arabic element in Philippine life, brought from India and possibly reinforced by the Spaniards whose culture in the sixteenth century contained many Moorish traits. The superimposed squares with pendant diamond shapes embroidered in blazing scarlet and egg-yolk yellow and hazel brown dyed nito fern on the tops of Kalinga hats are reminiscent of fifteenth century Spanish jewelry and the fabric designs of Spanish Moors of the fourteenth century.

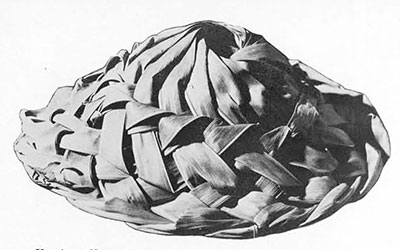

Pagan hats are small gay ornaments set on the back of the head. By comparison, most Christian hats, big and impressive though they are, seem drab. Like pagan hats, Christian hats may also provide places to store knickknacks. Some have sewn-in rolled inner crowns into which small objects can be fitted.

In the University Museum collection are ten types of hats from the lowlands of Luzon. The rarest of these are the hat of tortoise shell, thin as isinglass, translucent as amber, which comes from Camarines Sur, and the pagoda-shaped twillwork hat from Cavite, which is covered with silver flowers and leaves and topped with a tinkling silver finial. This costly city hat is a twin to the hat pictured in a hand-written book by Mr. Soden of Bath who saw it on a Manila cigar girl in 1841.

Most hats from the lowlands are less glamorous, depending for their interest on the natural differences in color and texture to be seen in bamboo. Artistic impulses find expression on the inside or at the peak of these hats. Many have brilliant linings of splashy cotton print or of coiled grasses wrapped with thin scarlet, indigo, or butter-yellow cotton thread. Rosettes of cloth may be pressed under an outer layer of hexagonal lacework to contrast with the black painted palm leaf lining below. Old tomato tin lids, tufts of hemp, cones and pyramids of shiny black nito twillwork set on petals of black velour, and tassels of red and blue yarn decorate the apex of these hats.

Museum Object Number(s): 50-49-1806

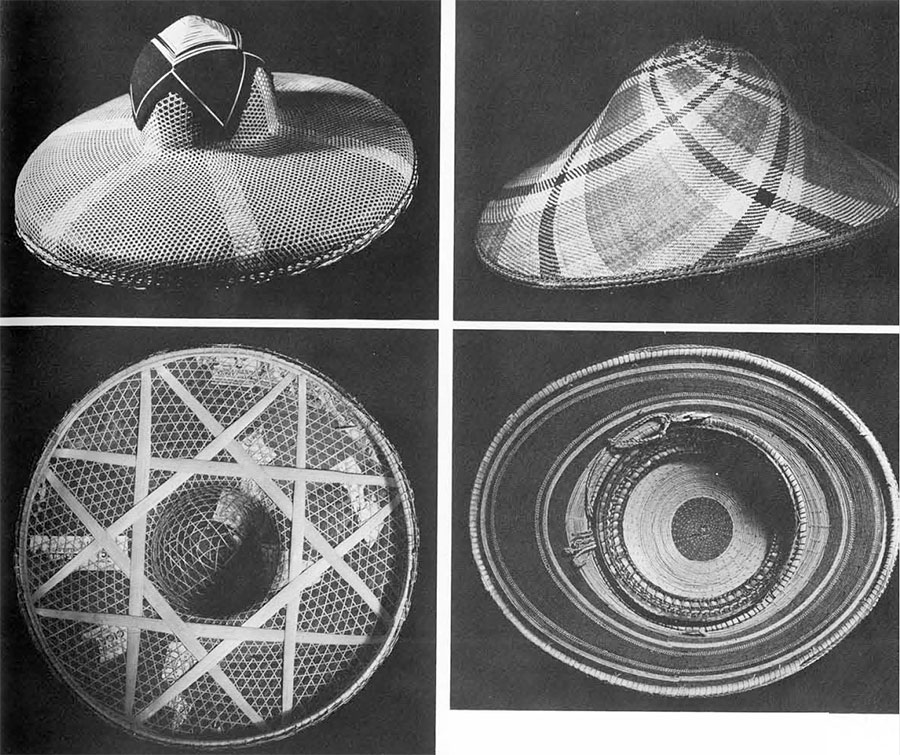

Whether made of goatskin or layers of palm leaves or halved gourds, or woven of or pandanus leaves in checker or twillwork or lacework hexagons as small as the head of a nail, lowland hats are always flattened discs or deep crowned turban shaped ovals that impress by mere size.

Hat-making was a man’s job in the pagan areas. Both men and women wove hats and wore hats in the lowlands, and worked in the Chinese-run hat factories that were common on the Luzon coast at the time these hats were collected. Berthold Laufer has pointed out that much of the basketry of the Philippines is “either made by Chinese or by the native tribes after Chinese models.” The influence of Southeast Asia on lowland hats shows up in twilling, the most popular weave, and in bamboo, the preferred hat material. Other techniques have been borrowed from China and Malaysia. Hexagonal lacework is common in old Chinese and Malayan baskets, as is the technique of using hoops for reinforcements and covering edges with knotwork and braidwork. Lined hats are found throughout Malaysia. The Philippine rain and sun hat is certainly a copy of a Chinese model, and in the remote mountain areas, Bontoc basket hats have a haunting similarity to the skull caps worn by early Chinese traders.

Many currents of culture have floated into the Philippines. From coolie hats to Mohammedan turbans to reproductions of U.S. Army hats, the Museum collection of headgear reflects these streams. Especially in the coastal areas the people were great copyists, but they adapted foreign styles to their own traditional materials–and models. How else may one explain a panama hat, copied from those worn by American businessmen of the Teddy Roosevelt era, but made with a saw-tooth top like a king’s crown? Or the U.S. Cavalry hat with broad brim and chocolate drop crown copied in wood? Or the brass buttons with American eagles sewn not to jackets but to the tops of Bontoc hats? Ot the tartan tam in Scottish clan solors, a line-for-line copy of a cloth model, done in buntal straw?

Whether a practicing Christian from Illocos Sur or a Kalinga head-hunter, the Philippine native was selective in his borrowing. These hats showed his ingenious talent for appropriating the whimseys and frivolities of Occidental and Oriental style, the pelf and plumage of the animal world, and the discards of Tin Can civilization. But they also show that he always remained true to the place and period in which he lived. His culture was firmly rooted in the Age of Bamboo, and he adapted whatever he borrowed from others to his native plant materials.

Museum Object Number(s): 50-49-1805 / 29-9-43