This page includes information that may not reflect the current views and values of the Penn Museum.

MATTO GROSSO

EXPEDITION, Inc.

Sound Moving Pictures : Science : Exploration

Near the end of the age of grand scale sponsored museum expeditions, inventor and former corporate magnate Eldridge Reeves Johnson developed a relationship with the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology that would indirectly result in a pioneering work in film technology history. E.R. Johnson was the President and co-founder of The Victor Talking Machine Company, the leading sound reproduction company in the world, and largest manufacturer of record players, an engineer and inventor. In December 1926, E. R. Johnson sold Victor which was again sold to RCA in 1929. At this time the variable area optical film sync sound recording system called RCA Photophone began practical Hollywood sound stage usage.

E.R. Fenimore Johnson, son of the Victor Talking Machine founder E.R. Johnson, became very interested in sound and film engineering technologies as well.[1] Both father and son were members of the board for the University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (Penn Museum), and E.R.F. Johnson became particularly attached to the development of the film collections, to the extent of publishing a manual on the proper storage and maintenance of motion picture film for museums and archives. E.R.F. Johnson funded a complete temperature controlled vault and a fund for a film library.[2]

In 1930, E. R. F. Johnson was asked by his friend and former University of Pennsylvania classmate John S. Clarke and Captain Vladimir Perfilieff to fund a zoological and ethnographic expedition to be undertaken and filmed in the Mato Grosso plateau of Brazil. Perfilieff was a Russian born artist and adventurer connected with the Explorer’s Club in New York. According to one account the budget for the expedition was quite large, one hundred thousand (Depression era) dollars, some of which they imagined they might recoup in film revenues.

Even before embarking, however, E.R.F. Johnson in various newspaper accounts demonstrated his intention that this Expedition had more serious aims, and also was aware that the group would be making film history in technology as well as content. Johnson stated in an interview taken by the New York Times before his departure, “These frontiers are rapidly disappearing. This is one of the last, for it won’t be long before the Brazilians will push in there, and the last of the native languages and customs will start disappearing. Much valuable knowledge of peoples, animal and plant life will thus be lost, as far as the world’s history is concerned. It is our intention to preserve as much of this as possible; we hope to be the first expedition to bring back actual sound recording films taken in the jungle” (NYT 3/6/31).[3] Here also, regarding sound, from an article titled Talkie cameras taken; “For the first time, according to Mr. Johnson, talking motion picture apparatus is being taken in to the field to record the voices of people and animals in their native locale. The expedition expects to bring back a permanent record for future use of ethnologists and naturalists”.[4]

A less scientific goal of the explorers, including Captain Perfilieff, was to capture on film the famous Latvian born adventurer/explorer Sasha Siemel spearing a jaguar in midair. Siemel had learned this technique from the Guato Indians of Brazil during his many years hunting there. Despite the creation of an artificial corral for the filming, they were unsuccessful in capturing this action on film due the speed of the event and lack of cooperation by most of the captured jaguars.

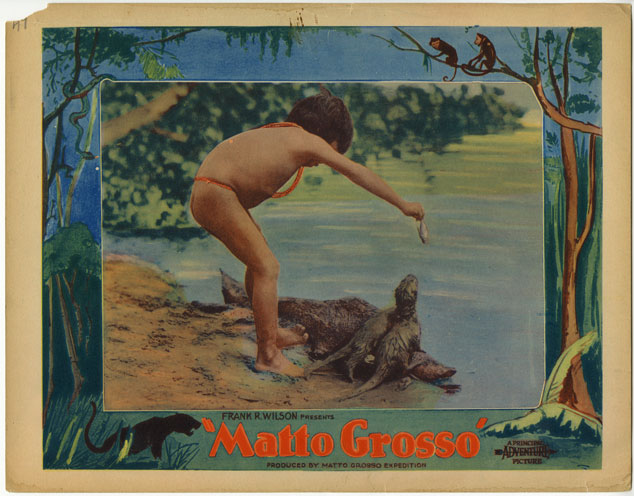

Many of the expedition party were primarily interested in the hunting aspect of the trip, which is reflected in large segments of the film. The see sawing and competing purposes creates a tension within the films’ editing in which it waivers between adventure film and scientific film, between Hollywood and academia, which may in part explain its later lack of success. Despite competing intentions, the resulting film, Matto Grosso, the Great Brazilian Wilderness (1931),[5] became by chance likely the first instance of documentary sound recording in the field.

The adventures and misadventures of the expedition are well documented in a series of New York Times articles which were conveyed via a radio transmission from the field camp, and articles written for the newspaper by Field and Stream writer David Newell, and others. A full account of the expedition can be found in Penn Museum Expedition articles by Eleanor King (1993) and Penn Museum Archivist, Alessandro Pezzati (2002).

As depicted in the film, most members set off from New York harbor on Western World of the Munson Line, December 26th, 1930 with a pack of hounds, lots of gear, and a Hollywood film crew. They arrived in Montevideo, Uruguay and proceeded by airplane and on the steamer Paraguay of the Lloyd Brasileiro lines, toward Brazil, January 30th and then to a ranch in Descalvado, Brazil to set up camp. Eventually they received permission to work in the Mato Grosso region, and proceeded to transport their burden of equipment and provisions on oxcarts and up nearly 2,300 miles of winding rivers in a boat the nicknamed “El Wunco”, arriving after a long time but without major interference.

[1]E.R.F. Johnson went on to create a production company and made a film called Undersea Gardens (1938) featuring pioneering undersea footage, recently restored by the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. For further technical information on this work see the Journal of SMPE http://www.archive.org/stream/journalofsociety32socirich/journalofsociety32socirich_djvu.txt

[2]E.R. Johnson (Sr.) may have played a role in early sound movies by recording non synch sound effects for the film Wings (1927). This research is being conducted by the Johnson Victrola Museum (DE).

[3]Also, the N. Y. Times article: “Explorers nearing jungle study goal” 2/1/31 “the speech and music of the human inhabitants of the jungle will be studied with the aid of apparatus new to exploration.”

[4]See also: “Explorer shows sound film of primitive Brazil tribe” Washington Post, 1/31/33 p.7 “Presenting the first sound moving pictures ever taken of primitive people, Vincenzo Petrullo of the University Museum of Philadelphia last night took members of the Archaeological Society of Washington on a two hour trip into a lost world of Brazilian wilderness. …Dances and other amusements of the primitive people were revealed, and one heard their language recorded on the sound film”.

[5]Copyright 1932, first screened January 1933.