Tea. With milk? With sugar? Probably both. When people imagine archaeological fieldwork, they likely think of shovels and trowels in the soil. But a crucial part of it – a foundational part – consists of copious amounts of tea. Often, cups of tea are brought in on a plate and passed around a large desk in someone’s office, before an audience seated in couches and chairs throughout the room or leaned up against the doorway. Or at least this is how it goes in India. This past summer, our team from the Paleoecology Lab and the South Asia Center at Penn spent three weeks conducting preliminary work on our new South Asian Landscape Trajectories (SILT) project – and none of it involved excavation. A lot of it however, involved tea.

The day after our PI (that’s “Principal Investigator” — the project leader), Dr. Kathleen Morrison, presented on archaeological contributions to climate models at the India International Center in Delhi, we sipped tea across five different desks at the Archaeological Survey of India offices. The eight hours we spent that day visiting colleagues and speaking with government employees make up a hidden bulk of pre-fieldwork.

When you’re part of a joint Indian-American project, chatting with local officials and scholars is necessary to make your research not only successful, but possible. As Penn archaeologists, we’re part of a whole ecosystem of knowledge about the human past. We may have our own research questions — and we certainly have our own interests — but the past doesn’t belong just to us. Our research could never exist without the dedicated work of other archaeologists and anthropologists, of historians, of environmental scientists, of scores of other scholars with other research interests, who bring different knowledge and different ideas than our own. Neither could we do what we do without the work of armies of government bureaucrats, who steward lists of sites and artifacts, coordinate their care, and ensure that they remain important sites of cultural heritage well into the future.

So archaeology isn’t just about digging or sorting through mountains of pottery, bones, and stones: it’s also about meeting people. And for that, there’s tea. Tea is the language of understanding, of friendship, of deference. It is indispensable in those moments (or hours) when relationships are forged, negotiated, tugged on. Face-to-faces are often the secret unspoken ticket to getting a research permit through or gaining access to an important artifact collection in government care.

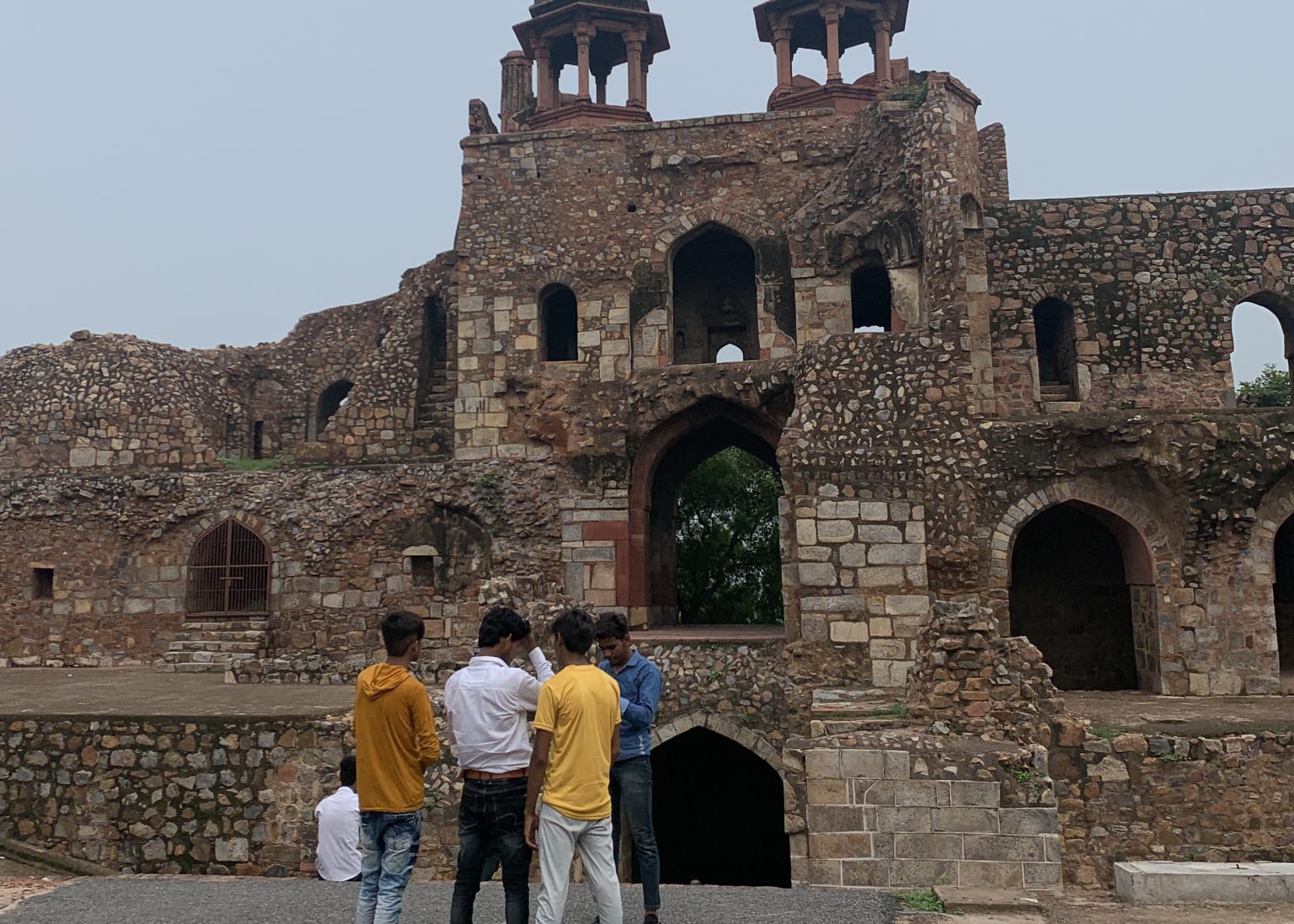

The sixth tea-desk of that long day of meetings with old and new friends was in an ASI office tucked into the fortification wall at Purana Qila, Delhi’s famous mid-sixteenth century Mughal citadel. This tea was enjoyed in the company of two enthusiastic ASI archaeologists, who had just finished whisking us through the artifact collections stored here from past excavations all over the country. As we sipped (and seized the chance to catch our breath), we reflected on one group of artifacts in particular — the group we had traveled here to see.

“Potsherds” are what archaeologists call broken pieces of pottery. It doesn’t matter where in the world you are — potsherds are probably the most common type of artifact you’ll find. People have made and used (and broke) ceramic pots for nearly 20,000 years. To put this in perspective, pottery is more than four times older than the pyramids at Giza. Ceramic was the world’s first synthetic material: the molecular transformations that occur when clay is fired by human beings do not occur in nature, making the invention of pottery the first time that people created an entirely new type of substance. Our long love affair with this anthropogenic ‘first-born’ ran like a thread from those earliest precious fragments in a cave in southeastern China through our own fingers to the porcelain tea cups we sipped from.

The potsherds we wanted to see had been excavated nearly three quarters of a century ago, at an archaeological site in northeastern Karnataka, South India — a place called Brahmagiri. For thousands of years, people had come to Brahmagiri to live, build monuments, and bury their dead. Society, technology, politics, religion, and environmental conditions all changed radically in South India during the occupational life of the site. While we can’t see these things directly in the archaeological record, what we can see — namely, pottery — changed a great deal, too. These changes in ceramic technology (e.g., the introduction of the pottery wheel) and styles can be assigned through careful study to specific time periods, geographical places, and groups of people. Once we have a rough idea of where and when a certain type of pottery was made and used (we call this a ceramic sequence or ceramic chronology), we can use potsherds of these known types to date other archaeological sites, or occupational levels within those sites.

At Brahmagiri, archaeological deposits stretch from the Neolithic (just over 2000 BCE) into the Middle Period (12th – 16th centuries CE). The built remains from this incredible timespan — megalithic complexes, a fortified hilltop town, and even three inscriptions with edicts of the emperor Asoka, carved in rock — are exciting enough for any archaeologist. The long human history of this place, though, is even more impressive when you consider the fact that Brahmagiri is miles away from a year-round lake, river, or stream. What did this limited access to water mean for the generations of people who lived in the area? How did they make use of their landscape? How did their actions over this long occupation change their landscape? With SILT, we hope to find answers to these questions.

Our next tea “appointment” brought us to the offices of the Indian Council of Historical Research, South Indian Centre in Bengaluru to catch up on the latest historical research of Dr. S. K. Aruni, the Regional Director. Dr. Aruni’s knowledge of Karnataka’s historical period can help draw important connections between our work on the prehistoric past and much more recent history up to the present day. When our “chat over tea” turned out to be an impromptu lecture for fifty or so intent Indian history grad students, we were relieved that Dr. Morrison came prepared with a presentation!

As it turned out, the discussion of environmental archaeology in the region was a hit! We had suspected this to be a sympathetic crowd, but when Dr. Aruni and his students lavished Dr. Morrison with the shawl, turban, and garland reserved for honoring distinguished Indian guests – to the great amusement of all involved – we knew we’d made some real friends. Of course, scores of group photos and selfies ensued.

We met with the next few tea breaks up the road a piece – in Hosapete, the basecamp town for fieldwork past in this semi-arid plateau of northern Karnataka. Here, we crossed paths with some stellar friends and colleagues: Dr. Smriti Haricharan of the Indian Institute of technology, Bombay; Dr. Ramya Bala Prabhakaran and her colleague Nithan, of the National Institute of Advanced Studies in Bangalore; Dr. Peter Johansen of McGill University in Canada; and Dr. Andrew Bauer of Stanford University. These folks are archaeologists, biologists, and environmental scientists — a refreshingly interdisciplinary group of talents that a project like SILT brings together. We talked shop, caught up on friends’ various goings-on, and enjoyed Hosapete’s famously spicy food. And, of course, some tea was sipped.

Before we left India, we paid a visit to Kadebakele, where Dr. Morrison has spent five field seasons over the last 20 years. “Kadebakele” means “final gate” in Kannada, the local language; the village grew up around the outermost in a series of impressive stone gateways that once allowed visitors entry to the magnificent walled metropolis of Vijayanagara, seat of a powerful empire that covered much of South India from the 1300s to the 1600s, CE.

Even before the walls of Vijayanagara grew to touch this place – even before there was a Vijayanagara – the site of Kadebakele was home to Neolithic, Iron Age, and Early Historic people, much like Brahmagiri was. Unlike Brahmagiri, though, Kadebakele sits right on the banks of the Tungabhadra river, a major year-round source of water for drinking and irrigation. Because of this, Kadebakele will be an interesting comparative example as we learn more about life at the new site.

We spent the better part of a day at Kadebakele, climbing the tower of granite boulders thick with thorny, invasive lantana, scrambling past the remains of a Vijayanagara-period wall to reach the bowl-shaped “upper terrace” that had been the center of Neolithic life at the site. Beneath our feet, the rock had given way to a thick blanket of earth — more than ten meters deep — a striking testament to the long human history of this place. From our vantage, we surveyed the landscape below, down to the banks of the churning Tungabhadra, gorged on monsoon rains. With the coming of the Iron Age some three thousand years ago, the people of Kadebakele had left their lofty settlement and moved down to the fields below, fields now brimming with rice paddies.

As it turned out, there remained one final tea break to be shared. Although we’d seen scarcely anyone on our way up, by the time we returned it was clear that the whole village knew we were there. Walking back, we met up with two old friends of Dr. Morrison’s, a couple of men from the village who had been excavators during archaeological field seasons past. Since scientific archaeology emerged in the 1800s, the overwhelming majority of archaeological labor — guiding, translation, carrying equipment, sifting soil and (of course) digging, among a million other essential things — has been done by local workers. Our friends from Kadebakele had honed their skills over many excavations, both with Dr. Morrison and with her students, and had become expert archaeologists — on top of being seasoned harvesters and taxi drivers.

As the monsoon clouds opened up (albeit only briefly, as is the norm in this arid part of the country), we sought shelter under the thatched overhang of a tea stall. Tea again! Well, somehow it never gets old when you’re with friends. We caught up, and Dr. Morrison joined the two locals in happy reminiscences. It wasn’t all happy, though. The men opened up to us about their struggles over more than two years of unabated COVID-19 pandemic. While infections were mercifully low in this rural region, work had all but dried up for many, and recovery had been agonizingly slow.

Still, as we finished our tea and the rain lifted, the mood remained lively. Here, at last, was more than just a moment to dwell on happier times: here was a moment to imagine a happier future, and the expert diggers confided in us that they would be pleased to see the shovelfulls of soil fly once more. For our part — now back in the States and busy beginning the year-long process of obtaining an official permit for SILT’s first archaeological work in 2023 — we’re excited for that day, too.

And, against all odds, we’re looking forward to many, many more teas to come.

We'd love to hear from you. Share your feedback about Penn Museum Voices Blog: info@pennmuseum.org

Explore More