Excavations at the ancient city of Nimrud, capital of the Assyrian Empire in the 9th and 8th centuries BCE, continued in the spring of 2024. These excavations are sponsored in part by the Penn Museum and directed by Penn archaeologist Dr. Michael Danti. I joined the team in 2023 and have been supervising work in the temples near the base of the ziggurat. As one of the team members, I wanted to talk a bit about what we accomplished—and in particular, about a mystery we encountered.

Nimrud is located in northern Iraq, about 30 miles southeast of the modern city of Mosul. It’s been investigated by archaeologists off and on for nearly 200 years. Parts of it were rebuilt as a tourist attraction, but in 2014 it fell under the domination of the so-called Islamic State (ISIS or DAESH). They destroyed buildings and large statues while simultaneously looting smaller objects for sale on the illicit market.

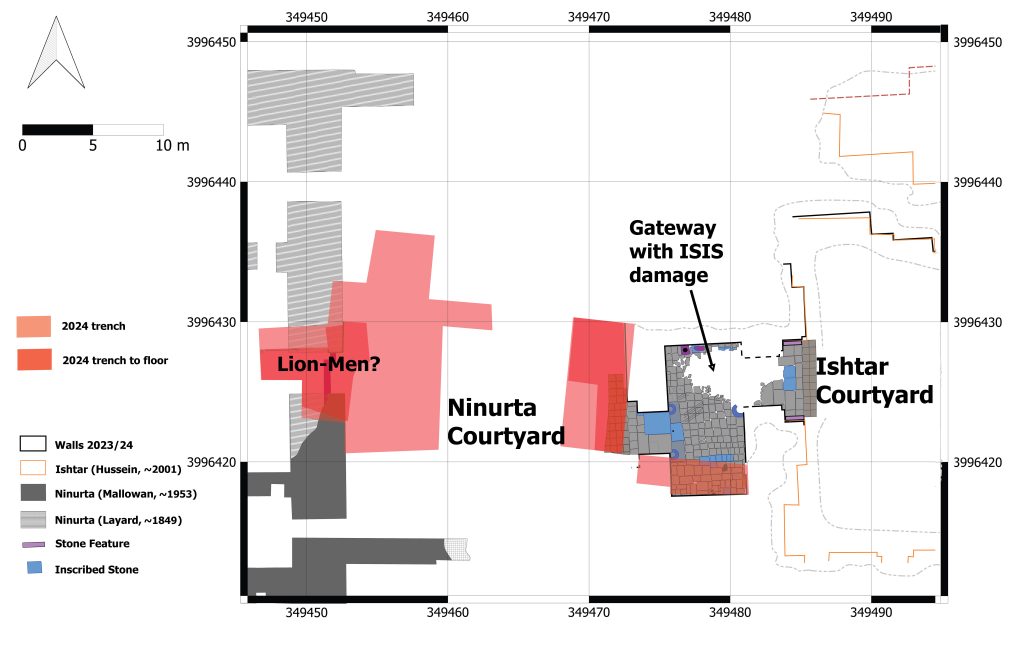

After ISIS was ousted in 2017, the Smithsonian began cleanup and documentation at Nimrud, principally concerned with what remained of the Northwest Palace. Then, in 2022, the Iraq State Board of Antiquities and Heritage asked Dr. Danti to help in other areas. He began in the Palace of Adad Nerari III and the temple complex of Ninurta and Ishtar. Ninurta and Ishtar were both important deities for the Assyrians, and some excavation had been done in their temples long ago—in the 1840s by Sir Austen Henry Layard and in the 1950s by Sir Max Mallowan.

Our team began by cleaning a pit that ISIS had ripped into the gateway connecting the temples. After documenting the damage, we turned the looter’s pit into a scientific excavation, expanding the trench to reveal the entire gate chamber.

We had to connect what we revealed with archaeological work that had been done in the surrounding area in the past. But the maps made by Layard and Mallowan were not clear on precise location, and many scholars have attempted to tie them together, leading to several possible reconstructions.

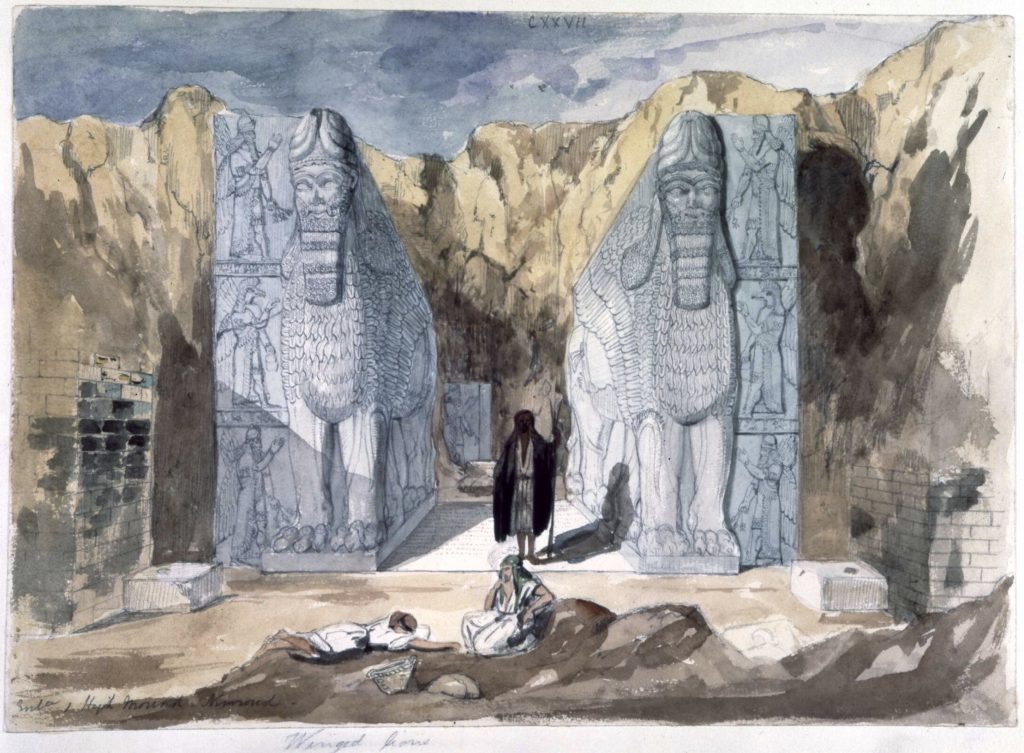

In order to solve the mapping problem, we established a grid on UTM coordinates. Then we began searching for previously excavated areas, now covered by soil wash. We knew that Layard had left in place two very large stone lion-men (a version of the protective spirit known as Lamassu, which are more typically bull-men). Mallowan had re-discovered the head of one of these lion-men in 1953. If we could find it again, it would connect all our excavations on a new map.

The lion-men should be easy to find since they’re enormous—around 3.5 meters (~12 feet) tall. But we knew the floor level in the Ishtar temple nearby was only a little over three meters down from the surface, so something didn’t add up.

The mystery begins.

It wasn’t easy to find the point where the lion-men must have stood because the older maps weren’t tied to modern coordinate systems, and they weren’t well connected to currently visible landmarks. We had estimates from the ziggurat, but ISIS had bulldozed much of that, changing the terrain. Nevertheless, we proceeded.

We put a trench at the point that seemed the best possibility.

No lion-men.

We expanded the trench in various directions.

No lion-men.

We dug down and found paving bricks and part of an ancient wall.

Still no lion-men.

The mystery continues.

We found modern trash even as we approached ancient pavement. At first, we thought it must have washed in after Mallowan left his excavation area. It dated from the 1970s through the 1990s, but we were working mostly in Layard’s area, and that would have been left much earlier.

The ancient wall we’d uncovered was made of bricks inscribed for Shalmaneser III, son of Assurnasirpal II, who originally built the temples. It was part of a doorway that led to the courtyard. There were glazed bricks fallen in many places, evidence of high decoration. And at the end of the wall was a large rectangular stone with two divots in it.

This stone looked rather familiar. In fact, it appeared in a watercolor illustration published by Layard.

We were in the right place, but the lion-men were not.

How does an object (let alone two) weighing several tons disappear? This couldn’t be a simple case of theft, and if ISIS had found them and destroyed them, they surely would have made a propaganda video about it.

Our excavation stratigraphy showed that a large pit was dug here after 1960 but before 1975. The purpose of that pit must have been to remove the lion-men. There were no clear reports of such an excavation, but records at the State Board of Antiquities were incomplete from that period.

After we returned to the States and began poring over old references, we finally solved the mystery. There was a brief mention in the Iraqi journal Sumer that two bull-men were moved to the Mosul Museum from Nimrud in 1973. A photo in that summary article proved these were not bull-men, but lion-men.

Although we’d solved the mystery of how such large things could “disappear” and where they went, the final result is not a happy one. Because they were in the museum when ISIS took Mosul, they were destroyed. Fragments of some statues are being put back together even now, with an expected reopening of the Mosul Museum some time in 2026, but whether these two lion-men will ever be seen again is still in question.

W.B. Hafford is a Research Associate in the Penn Museum’s Near East Section. Learn more at his YouTube channel Artifactually Speaking.

We'd love to hear from you. Share your feedback about Penn Museum Voices Blog: info@pennmuseum.org

Explore More