During my recent visit to Papua and New Guinea, I had occasion to spend a weekend at the Sogeri Education Center, near Port Moresby. Operated by the government, the Center is primarily for training native school teachers and clerks. Mr. Keith Little, a member of its faculty, has stimulated the students to paint pictures illustrating their home life. A number of pictures were recently exhibited in Australia. The four paintings reproduced here (Figs. 26 to 29) are the work of Mea Idei, who comes from the Kiwai-speaking village of Boje near the mouth of the Fly River in southwestern Papua. They all illustrate the following legend, which Mea Idei wrote for Mr. Little. Before writing it, he felt constrained to send to his father for permission. He explained to me, that the story is associated with a cycle of ritual for promoting the growth of sago and taro. His father is the specialist who controls these rites in Boje village. They and the associated legends are the private property of his family and are not supposed to be divulged to outsiders. The members of Mea Idei’s family must observe a number of taboos as well. They never eat the head of a pig, but bury it in the earth as an offering to Nugi, who figures in the story told here. When they kill a species of snake which they call labanalo, they similarly bury it for Nugi. They cannot eat nor kill crocodiles. If other people kill a crocodile, they must report it to Mea Idei’s father, who absolves them. Otherwise they will be sick and must pay Mea’s father for a cure. There are several other specialties of this sort in Boje village, associated with snakes, birds, wallabies, and coconuts. Mea Idei’s father is a specialist in wallabies as well as crocodiles, and there are totemic legends deriving people from the wallaby as this one derives them from the crocodile. Mr. Little edited the story as it appears here, and kindly made available to the Museum a copy of the manuscript. He states that, in editing it, he has not altered its substance in any way, but has confined himself to putting it into standard, story-book English.

W. H. G.

These things happened very long ago-very long ago indeed-for in those clays spirits were the people of the beaches and jungles and were still very close to animals, living shy, timid lives, as animals do today.

Image Number: 47036

Men and animals lived very close together for they were still friends. Indeed many animals lived then that do not live now-part man, part snake, part bird, part fish, and only a few men had become true men. And spirits ruled the world by magic and anything was possible. But now that the spirits have crept away and men are beginning to learn to control the life of the world and to be powerful, fishes no longer can come out of the seas and rivers, the cassowary has forgotten how to fiy, and the cuscus remains in the trees. The only animal which remembers some of the old ways is the crocodile, for he can live as a lizard or as a fish.

The crocodile is the father of my tribe. This is how it happened.

In those far off days when there were so few men, a man named Spila lived all alone in the dim, green jungle. There he lived and felt lonely for he had no friend to share his food, or to help him make a shelter. Worst of all, there was no one to talk to about his adventures or to make plans with or to say “How nice this paw-paw is to eat,” or to talk to about the rain and the sun and the sky.

So Spila took a log of buso wood and cut it and carved it till it took the shape of a man. But it was only a man of wood-it did not move its arms; it had no light in its eyes; its lips remained closed.

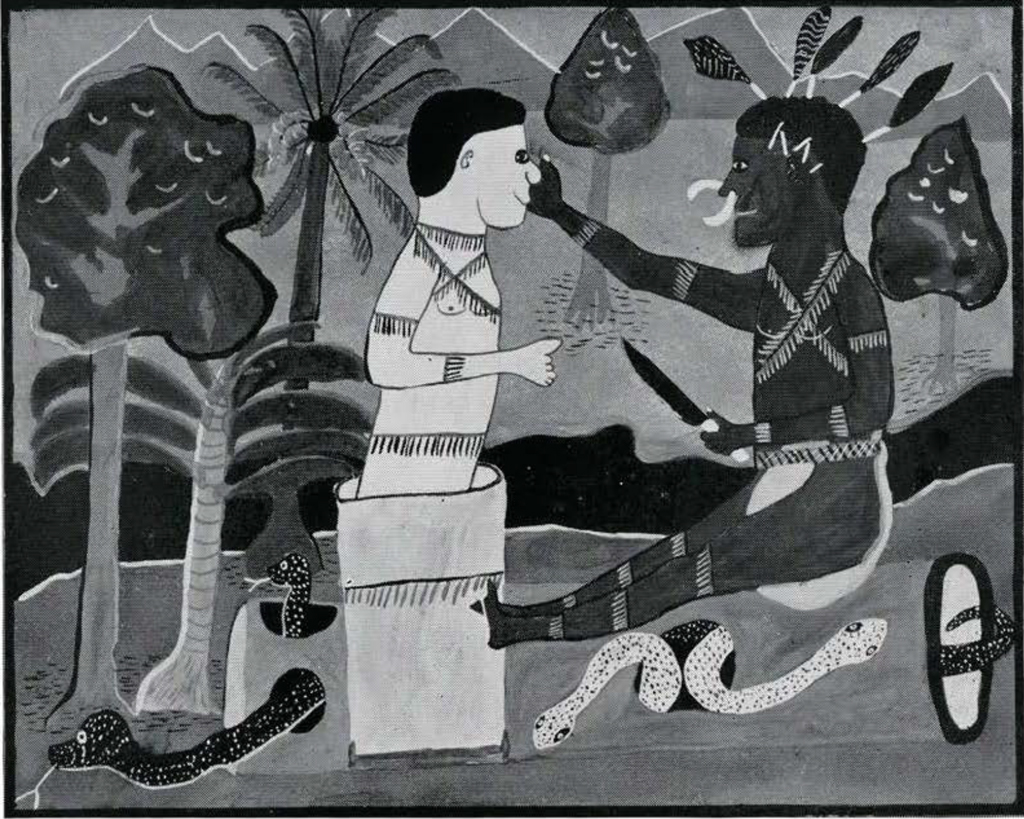

Spila sat before it and thought: I am alive because I eat sago. He offered some sago to this friend he had made but the wooden man remained still, and did not take any. Spila thought: my friend cannot open his mouth to eat sago. I shall paint his face with sago-milk. So he painted his friend’s face with the milk and his eyes opened and light came into them. And his mouth opened and he made a noise like a crocodile makes, and breathed air in through his nostrils (Fig. 26).

Still he could not move, so Spila danced a dance of happiness, stamping his feet on the ground and showing by the movements of his hands and arms how he had carved a man out of buso wood and had painted his face with sago-milk. Then the wooden man moved his arms and legs and began to dance with Spila.

When they had danced, they sat down together and Spila began to talk to his friend for he was happy and had many things to say. But his friend shook his head and could not understand, for his ears were not open and he could not hear. Now Spila got his drum and began to beat on it and to sing, and his friend stood up and danced to Spila’s drumming, and he sang his song with him. And so, singing and dancing, they were both happy, and the song and dance both told of happiness.

Image Number: 47037

When they had danced enough, they sat down together and began to talk of many things; about the sun and the rain and the sky; about the good taste of food; about the wonderful things that men can do in this world; about the spirits which live forever and the animals which live and then must die.

“But what am I?” asked Spila’s wooden man. “And how did I come into the world?”

“I made you,” Spila answered. “Yesterday you were a block of buso wood and I fashioned you from it with my skill.”

“I know nothing of yesterday,” said Spila’s friend.

“No, yesterday you were not alive,” said Spila. “How came I to be alive?”

“The food which sustains my life gave you yours.”

“The tree from which you took the wood to make me, it is not alive?”

“Yes,” answered Spila. “It lives. But it does not know that it is alive and so it cannot show the world that it is good to be alive. You, yourself, were not truly alive until the rhythm of my drumming and the sweet tones of my voice singing entered your ears and awoke the spirit in your heart. Now you know that you are alive.”

“I know that I am alive,” agreed Spila’s friend. “But these things I do not know. What am I? Who am I? Why am I alive?”

“You are a man,” answered Spila. “For I am a man and I made you like myself. Who you are I cannot say, but your name will be Nugi. Now you know who you are-you are Nugi. And you are alive because I fashioned you-and I fashioned you so that we might live together in happiness.”

“But I am I. Perhaps what pleases you may not please me. I may please myself?” asked Nugi.

“Yes,” answered Spila slowly. “Yes . . . you may please yourself.”

“What would please me most would be to have a companion like myself. Teach me to make men,” said Nugi.

Image Number: 47038

So Spila showed Nugi how to fashion men out of buso wood and how to give them life with the milk of the sago, and to give them a spirit in their hearts by singing and dancing. He made three more men so that Nugi might learn properly how to make them, and when they asked how they came to be alive and who they were, he named them Maiori, Sawoiama, and Uledade. And when they asked why they were alive, he told them what he had told Nugi. But they answered:

“Weare four men now. We are alive because you fashioned our shapes, and gave us spirits in our hearts. Our names are Nugi, Sawoiama, and Uledade and we are the same kind, but you are of another kind.” And they turned their backs on Spila.

“But you are mine,” cried Spila. “You do not know how to live. There are many things you should know which I may teach you. Without this knowledge, you cannot be happy in your lives.”

“We know enough,” they replied over their shoulders. “We know that we are men. We know we can keep alive by eating sago, and as for being happy, are there not dances, and can we not sing and dance? More than this, we do not need to know.”

Then Spila sadly turned his back on the men he had made and went sorrowfully into the jungle.

So Nugi, Maiori, Sawoiarna and Uledade were left alone to live and be happy, and many animals came out of the jungle-for animals were still the friends of men-to watch them eating sago and singing and dancing. But they did not sit down to talk very much, for they knew what they knew and did not wish to know more.

But one day, while they were resting, Maiori said: “My friends, I’m tired of eating only sago. I will catch one of these animals and eat it instead. Will you help me catch one?”

“No,” said Nugi and Sawoiama. “Sago is our food. We will not harm animals by killing and eating them.”

“Yes,” said Uledade, “I, too, am tired of eating sago. I will help you to catch an animal and will eat it with you.”

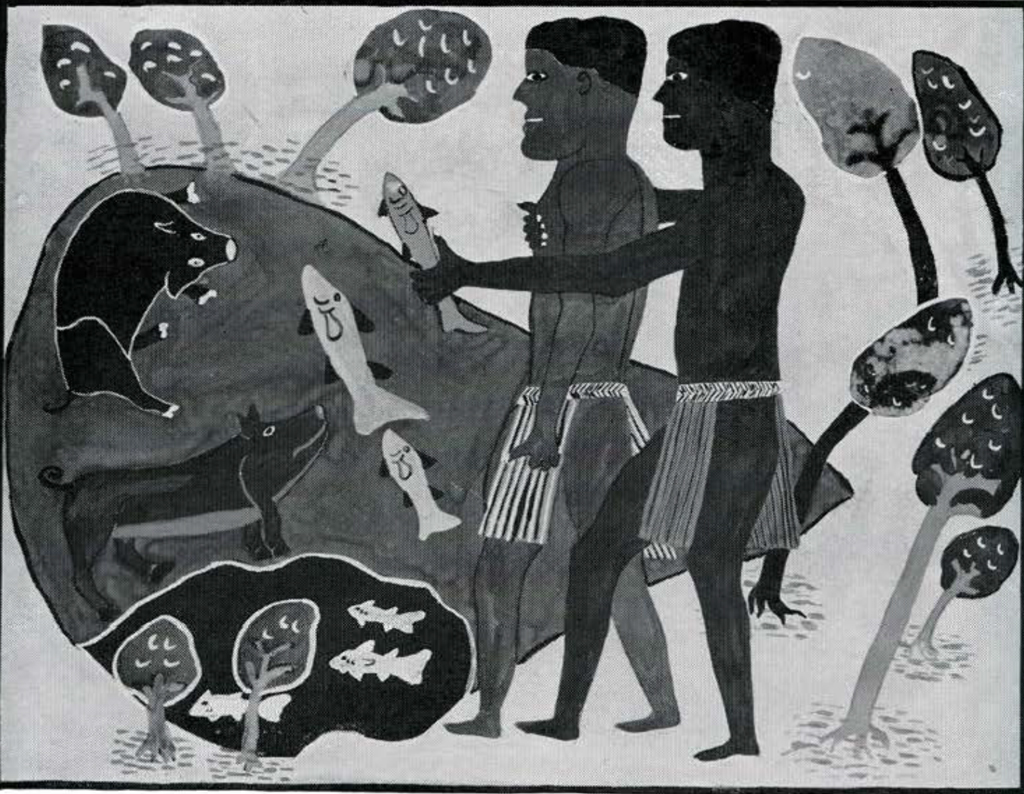

So Maiori and Uledade got up and caught two pigs and ate them, and they caught fish and ate them (Fig. 27). At once all the other animals ran away and hid, and some ran to Spila and told him what had happened. Now Spila wept because he was sad.

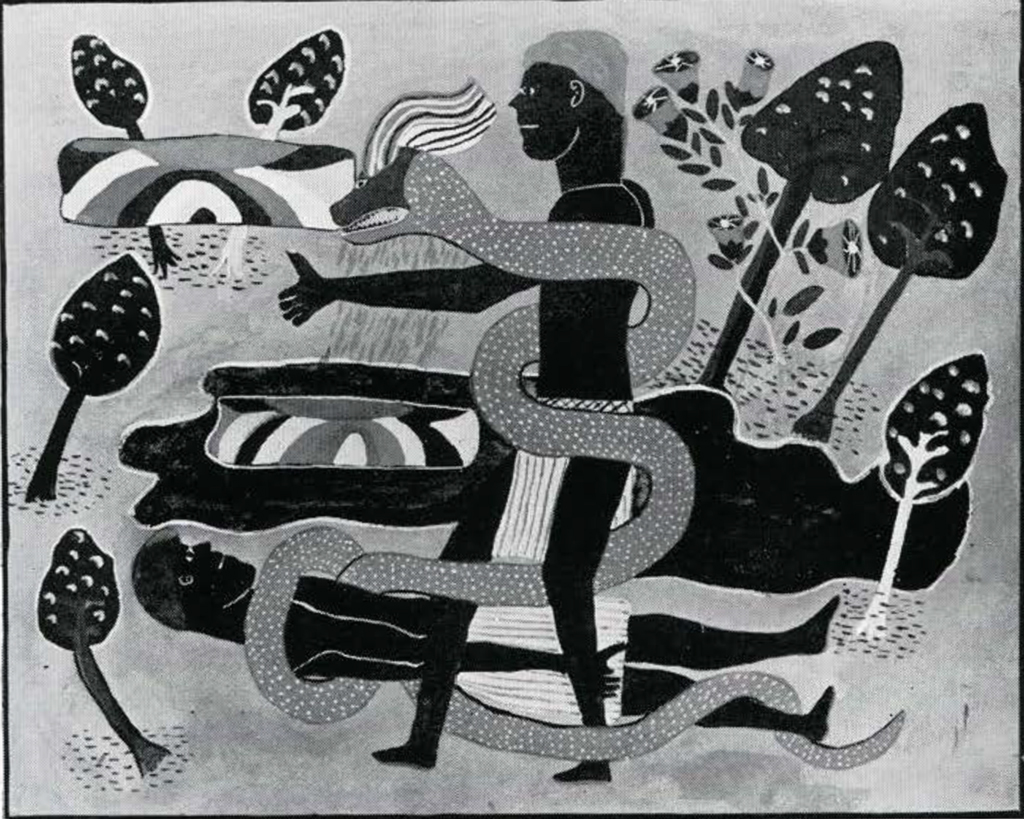

As for Maiori and Uledade, when they finished eating the pigs and fish they slowly began to change their shape. Nugi and Sawoiama went a little way off, for they were amazed, and watched their two friends change until their bodies were the body of a crocodile (Fig. 28); but their heads, arms, and legs did not change. So there were two men, Nugi and Sawoiama, and two half-men half-crocodile, Maiori and Uledade.

So, because Maiori and Uledade had made all the animals afraid of men by killing those two pigs and by catching fish, they themselves were afraid of Nugi and Sawoiama, because they themselves were now half-animal.

Image Number: 47039

And Maiori and Uledade, because they were the friends of each other and not the friends of animals, could not now be the friends of Nugi and Sawoiama. So Maiori and Uledade went one way to a place called Paso-which is at the end of the earth-and Nugi and Sawoiama went another way to the other end of the earth to a place called Sege.

At Sege, Sawoiama died. And there was no buso wood at Sege. Nugi was very sad and lonely and he blackened his face with usi and went back and forth through the jungle crying “Spila! Spila!” for he wanted to have a friend because a lonely man cannot be happy.

But Spila was at the other end of the world and could not hear Nugi. He was watching, sadly, Maiori and Uledade.

Maiori and Uledade, too, were feeling very lonely, but there was buso wood at Paso, and they began to make companions for themselves. They tried to make them in their own shape, half-man half-crocodile, but always the shape turned into the shape of a man. Time after time they tried, but each time Spila turned the shape into the shape of a man and gave each shape lips and spirit.

Time after time, time after time, they tried until there were hundreds of men, alive and with happiness in their hearts. Then Maiori and Uledade got tired of making men, and Spila was free to go away. (All those men that Maiori and Uledade made became my tribe-the crocodile is the true father of my tribe.)

Nugi was still wandering about crying “Spila! Spila!” and now Spila heard him. So he went to the end of the world where Nugi was, and spoke angrily to him.

“Nugi,” he said, and his voice was harsh, “you are the first man I fashioned. I fashioned you so that I might share my happiness with someone, for pleasure shared is pleasure doubled. But you care for nothing but the company of those that I fashioned after you simply for your own sake, and when they turned their backs on me, you also turned your back on me.”

Nugi was silent, for he was ashamed.

“Now you come crying ‘Spila, Spila’ for you want my companionship again.”

Nugi did not speak for he was still ashamed. But he bowed his head and looked at the ground, embarrassed.

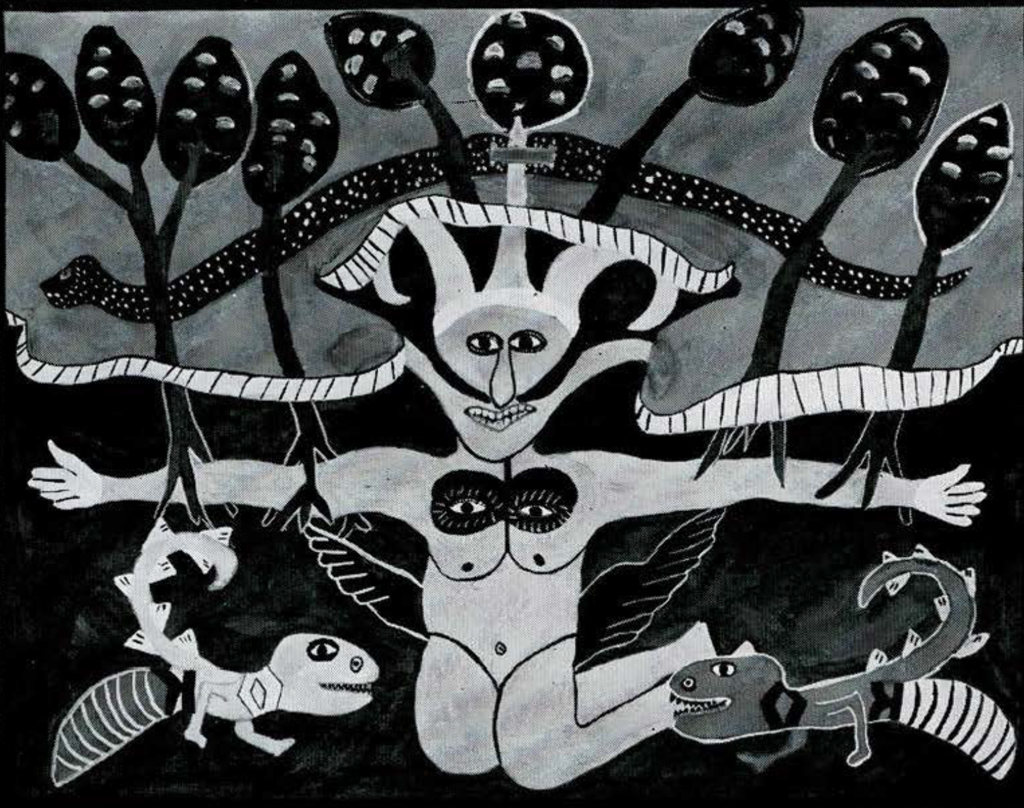

“Now I give you a choice,” continued Spila. “Either go away at once and live a lonely life crying ‘Spila, Spila’ while man lives on the earth, or pick up the world at this end and place it on your shoulders so that here you may stay forever, and here I might always find you when I need companionship and someone to talk to.”

Nugi was silent, but he bent his back and placed the earth on his shoulders. And he is still there-supporting the earth on which dwell my people whose true father is the crocodile (Fig. 29). And Spila passes back and forth, bringing him news of what is happening in the world.

But Nugi is still silent; Spila does not bring any news from Nugi and Nugi’s end of the earth to my people. And so we only know what we know-not why we are alive, nor what is happening beyond our part of the world.

But we know that Maiori and Uledade are our true fathers; that sago and pigs are good to eat, and that singing and dancing bring happiness.

KEITH LITTLE

Sogeri Education Center