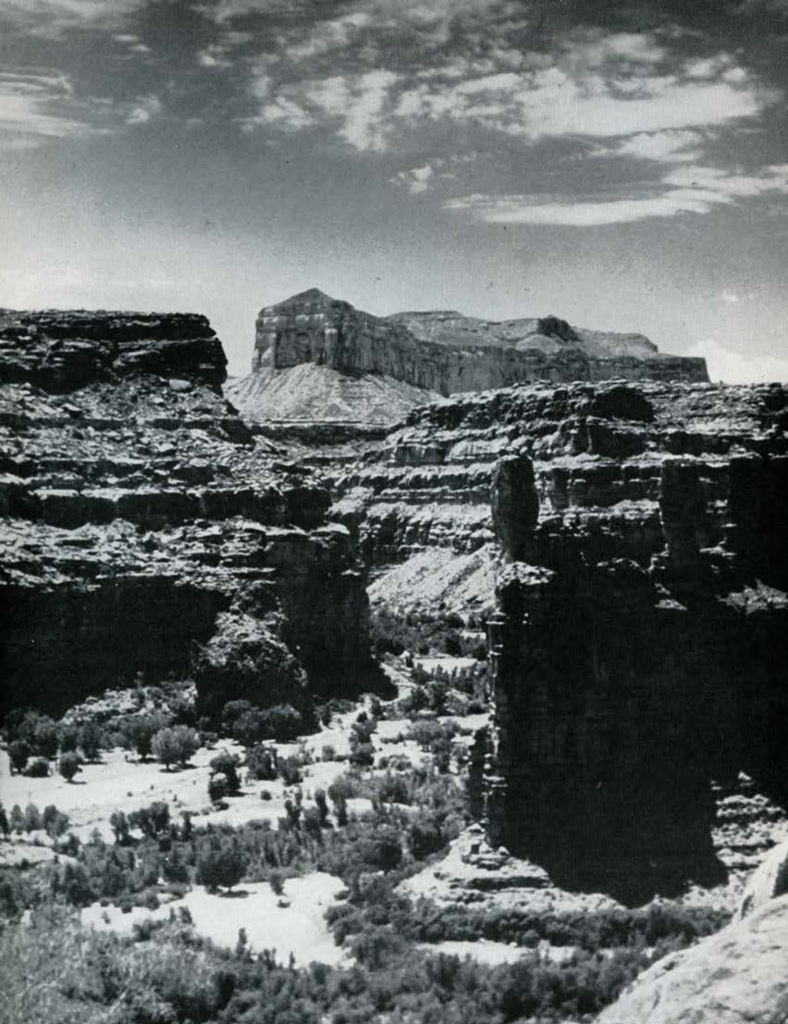

The American Southwest is known the world over for its unique, colorful, almost frightening beauty and there is no more awe-inspiring part of it than the Grand Canyon country in northern Arizona. Here, in the past ten million years or so, the Colorado River and some of its tributaries have carved a mile-deep wonderland into the Kaibab Plateau. The place is a network of canyons with the majestic Grand Canyon itself at its center. Nearly all of these gorges are being cut by intermittent streams born of the melting snows and summer cloudbursts. Therefore, throughout most of the year the floors of nearly all of them are dry and desert-like. One of these chasms, however, is richly green, for through it, from an inexhaustible source, flows a small but bounteous stream. This oasis is called Cataract Canyon and it has been the home of the Havasupai Indians for hundreds of years.

Image Number: 56813

In historic times, at least, the Havasupais have certainly lived where they do now-in and around Cataract Canyon. The early Spanish records make frequent reference to such people as the Coninas, Cosninos and Coconinos living in this same region. There is every reason to believe that many of these references, by names which are corruptions of a Hopi expression for their western neighbors, were to the Havasupais. The legends of these people, when correlated with what is known of the pre-Columbian history of the southwest, indicates that they have inhabited the Grand Canyon country since perhaps as early as 800 A.D.

The first positive record of the Havasupais was made by the Franciscan missionary, Padre Francisco Tomas Garces, who. on June 20th. 1776. was guided into Cataract Canyon by a party of Walapais. His diary tells us that the people he found there were extremely friendly and, in fact, they attended him so royally and feel him so well that he remained five days. The good Padre’s brief, but vivid, account of his passage into the canyon from the plateau above anticipates most of the subsequent descriptions of this journey, for it presents a picture of incredibly tortuous trails hanging over horrible abysses. Few visitors to Cataract Canyon have been willing to confess that they did not risk their lives getting there. It is true that some three thousand feet of rock walls surround the canyon floor, but the trails, though rough, are adequate for foot and horse travel. Passing in and out of the canyon is no lark to be sure, but neither is it as grueling an experience as it has often been pictured. It is far more fatiguing than frightening.

Throughout the literature on Cataract Canyon, especially that of a more popular nature, the isolation of this place is always emphasized. It may seem so to outsiders, but not to those who live here, for there are at least a dozen trails from the plateau to the village in the canyon called Supai. In aboriginal times, of course, they needed to be suitable only for foot travel, but, since white contact, seven of them have been modified for horse trails. They range in length from eight to fifty miles. Not all of them are constantly maintained, but the Indians are never limited only to the two trails by which most of the outsiders enter and leave. The foot trails are all relatively short, the longest being only three and one-half miles. All of them, however, begin from points on the plateau which are extremely difficult to reach by automobile and are, therefore, restricted to occasional use by the Indians only.

Image Number: 56815

The visitor today may approach Cataract Canyon either from Grand Canyon or from Peach Springs on the Walapai Reservation. Grand Canyon may be reached by railroad and Highway 66 passes through Peach Springs. At Grand Canyon one may get a ride with the Indian mailman to Topacoba Hilltop over a road that is hardly a road at all. Twice a week mail is taken by truck from the Grand Canyon post office to Hilltop where it is exchanged for mail coming from Supai. At Hilltop the letters and packages (and visitors, unless they choose to walk) are loaded upon horses and mules. The animals are then turned loose and they dutifully follow the fourteen-mile trail to the village below.

If one chooses to take the Peach Springs route, it is over sixty miles from this little town to Walapai Hilltop, the other point on the rim of the canyon where it is necessary to trade wheels for hoofs. The road from Peach Springs is a good one and the trail from Walapai Hilltop to the village is only eight miles long. It is this way that most visitors come.

The lasting impression one receives when descending any of the trails is one of almost overwhelming awe. The great walls rise higher and higher and as the gorge they enclose grows so narrow that sometimes the sky is scarcely visible, it seems that the canyon has claimed for itself the puny creatures plodding through it. The experience is inspiring, exhilarating and sometimes uncomfortable. To heighten the sensation a hot, dry breeze stirs constantly and except for an occasional desert plant that stubbornly remains green, everything looks as if it hasn’t seen water for a thousand years. Just as one begins to adjust mind and body to this oppressive, dry heat, however, the canyon takes another of its endless turns and suddenly the air seems to cool and freshen. At first the senses only suspect this new presence, but after rounding another bend, the eyes and ears confirm it, for a luxuriant growth of small willows and cottonwoods appears and the welcome, singing sound of a stream can be heard. Here, seeping from the canyon floor about a half-mile above the village, is the water that makes Cataract Canyon habitable. As the tiny stream trickles along, many small springs add themselves to it until, a few hundred yards from its birthplace, Cataract Creek is full grown.

Image Number: 56817

As the creek hurries busily on through it, the canyon widens abruptly to nearly a quarter-mile across and neatly fenced fields and orchards spread out between the great reel walls. This is the village. This is Supai, the home of the Havasupai Indians.

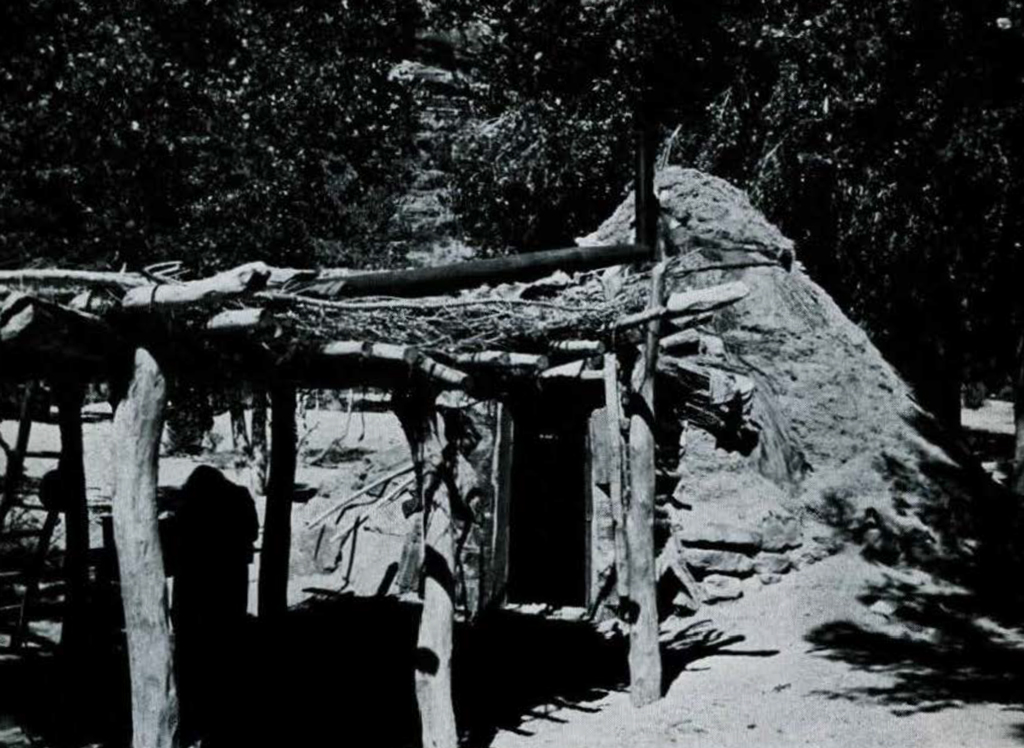

The village is spread all over the canyon floor. The only concentration of buildings is that of the homes built by the government for the agent and a school teacher. Not far from them is the small schoolhouse, the mission, and the Indian store. The Indians have tended only slightly to cluster about this center of community activity. Many of the aboriginal dwellings have been replaced by small wooden frame houses which were first introduced by the government as a relief measure after the tragic flood in January, 1911, when five clays of thaw on the plateau was followed by several more days of heavy rain and the accumulated water rushed through the canyon in a flood crest which utterly destroyed the village and most of the fields. Some of the old earth and pole houses may still be seen. Many of the families prefer them to the more modern ones for they are cooler in the summer and can be kept warmer during the cold weather. Many of these old-style houses are conical in shape but most of them are longer than they are wide and have sloping roofs of dirt which nearly reach the ground on either side. Very few of them are made of stone.

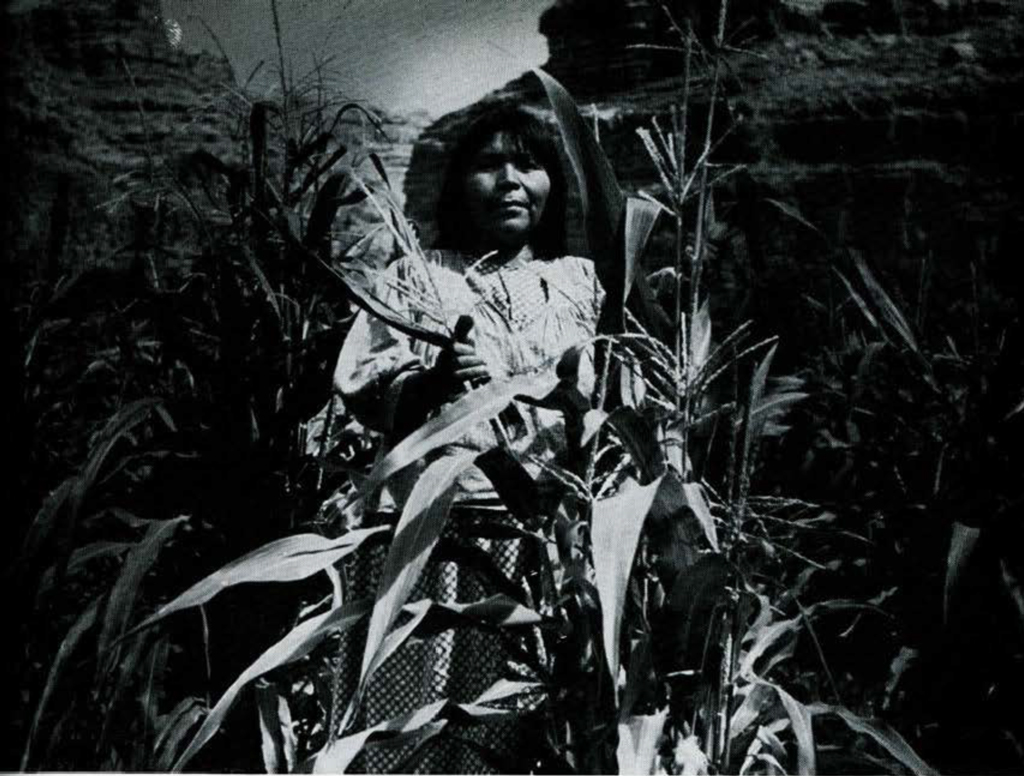

In passing through this wide part of the canyon one may see a great many small fields. Most of them are planted with corn but close examination shows that growing in the same fields between the corn plants are beans, squashes, pumpkins, sunflowers, watermelons, tomatoes and potatoes. Many of these plants were introduced after white contact, of course, and among them are the fruit trees which stand in orchards in some parts of the canyon and grow along the trails everywhere. Peaches, apricots, figs, pears, and apples are now part of the standard diet in Supai and even pecans, plums and pomegranates are grown.

Image Number: 56819

Perhaps a mile downstream from the point at which the canyon spreads out to make room for the village, it quickly narrows once more. It is here that the first of three magnificent waterfalls may be seen. By this time Cataract Creek is the size of a small river and has become brilliantly blue. Carbonates of lime, which become more concentrated as the stream flows along, give it this color. The breath-taking, snowy-white falls plunging as far as 220 feet over vermilion cliffs into turquoise pools is a sight which no one who has seen it will ever forget. Though these falls are only a mile or so below the village, it is strange but true that several of the women who are middle-aged or older and have lived here all their lives, have never taken the trouble to see them.

Cataract Creek beautifies this canyon to be sure, but probably the most vital use to which the water is put is that of irrigation. Above the village two log and brush diversion dams scoop water from both sides of the stream into ditches with a speed of flow sufficient to divert a considerable amount of water. It is then carried through the village and into the fields. Most of the irrigation canals are simply small ditches dug in the sand, banked slightly on the sides. The main ditches are as much as two feet deep and three feet wide, but the laterals are much smaller. These are dug from the main ditches to the individual garden plots which may then be watered as necessary. Each field is divided by long mounds of earth into sections which are watered one at a time by letting the excess from one into the next until the entire field is well soaked. Whenever the water must be carried across the mouths of side canyons where ditches would be frequently washed out in storms, small aqueducts have been constructed with piping and cement. The Indian Service has made plans to install new diversion clams and three new aqueducts with permanent footings at a cost of many thousands of dollars. The old system is a primitive one, but it has stood the test of time, for the Havasupais have been irrigating for centuries.

In preparing the fields for the first planting in April, the old buckthorn planting stick as an agricultural tool has given way to the plow, scraper, harrow and disc as well as shovels and hoes. Most of this equipment, along with several cultivators, mowers and one tractor, belongs to the Tribal Council which rents it out for services or money. Unfortunately, most of these tools are badly cared for since the Havasupais seem to have little mechanical ability. Men, women and children plant, but the men do most of the field preparation, irrigation and fence building and repair. The age old prayer at the first planting is still a very important part of this spring activity.

Image Number: 56818

The more than 280 Havasupais speak a dialect which, along with that spoken by the Walapais, the Yavapais and the Tonto, has been classified as the eastern division of the Yuman stock. Havasupai and Walapai are particularly close, the dialects being no more different from each other than are “Bostonian” and “Brooklynese.” The cultural affinities of these two groups are equally close and their members live comfortably in each other’s midst and frequently intermarry.

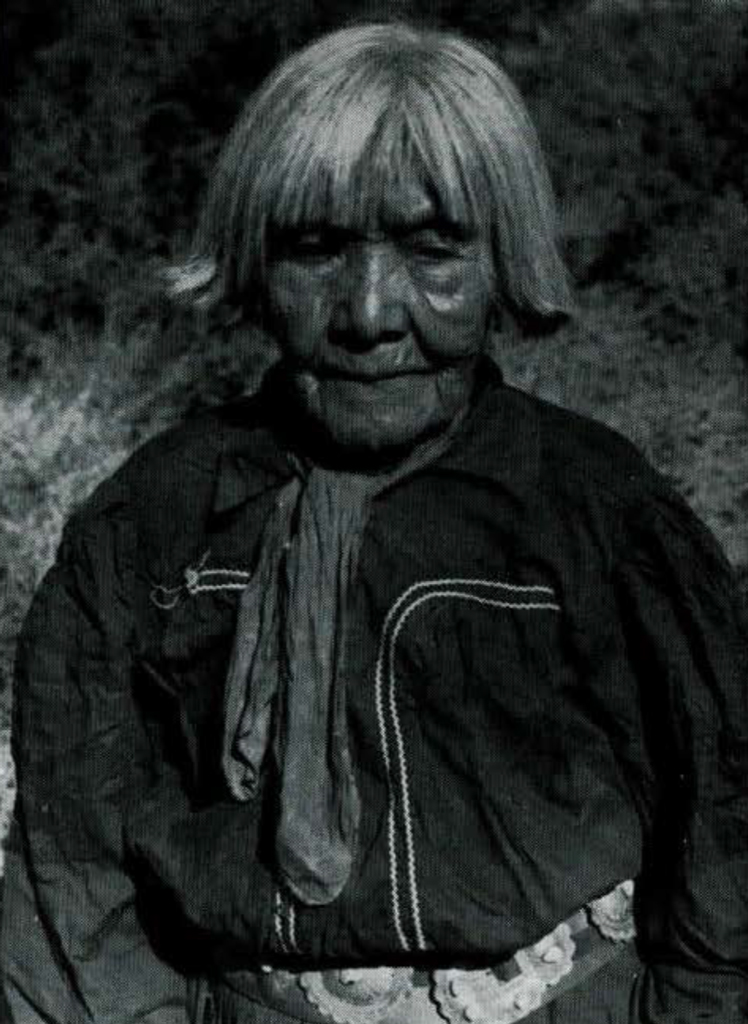

Physically the Havasupais bear a close resemblance to the Indians of the Lower Colorado. They are of medium to short stature and inclined to fatness. Their complexions are relatively light and they smile easily and winningly. It would not be an overstatement to call these people easy-going. Unpleasantness arises occasionally here as it does wherever human animals live together, but in Supai it seems of a less offensive nature. It is peaceful place where people are loathe to interfere in each other’s affairs, yet ready to help when asked.

Leslie Spier once pointed out that culturally the Havasupais are closely associated with the tribes of the Great Basin. This is especially true of the material, economic and the social aspects of the culture. At the same time, these people are primarily agriculturalists like their eastern neighbors, the Pueblos. This places them in a distinctly intermediate cultural position.

Image Number: 56821

In aboriginal times, when the tribe was often smaller than it is today, early spring found the Havasupais returning to Cataract Canyon from the plateau where they had spent the winter hunting and gathering pinon nuts and other wild seeds. The spring planting was done and the dirt covers on their houses repaired. It was at this time that much of the food, which had been dried and stored the year before, was eaten.

During the summer everyone lived in the canyon, though trading expeditions were often sent out to neighboring tribes. When the corn and peaches ripened in September, the harvest was taken in and a dance held to which Walapais, Navajos, and Hopis were invited.

By the middle of October an exodus of families and groups of families began and within a month the entire population moved up to the cedar thickets on the plateau where semi-permanent camps were established and once more the winter activities began. This annual cycle has changed considerably, however, in the past half-century.

The food-getting economy of today is no longer divided between the spring and summer agriculture and the hunting and gathering of fall and winter. There is a concentration by both men and women on agriculture and remunerative employment on the plateau. This makes it possible for families to depend on food purchased from the store as well as that which they grow. The hunting and gathering aspect of their economic life has been nearly given up, making the seasonal migrations unnecessary. The village is now the center of activity throughout the year.

The Indian Service maintains a clay school in the canyon for the young children in which classes are held during the winter months. This, of course, also operates to keep many families in the village all year round. Although some entire family groups live out of the canyon in Indian camps at Grand Canyon, Williams, and a few other small towns, it is more common for the family home to be maintained in Supai while one or two members of the group work outside temporarily. In the spring and fall when planting and harvest are carried out, it is essential for the whole family to be on hand and most of them are.

Image Number: 56822

Image Number: 56823

The store in the village provides at least as much food as the fields do. It is open every clay from ten o’clock to noon and stocks an amazing variety of canned foods, and staple goods. It is owned and operated by the Tribal Council for the benefit of the tribe and the prices are far more reasonable than one would think, since every item in the store must be packed into the canyon on horseback. The shelves are stocked with canned meats, spaghetti, chili, soups, and many kinds of sweets. Fresh lemons, canned orange juice, cigarettes, canned milk, Kleenex, and even eggs may be purchased there. Favorite brands have become firmly established and such items as Lucky Strikes, Carnation Milk and Tide washing soap are preferred. The new package cake mixes have been as much a boon to the women of Supai as they have to the women of Cincinnati.

In addition to running the store, the Tribal Council also appoints one of the tribal members to function as a “tourist manager.” The Havasupais are well aware that their most valuable resource is the unmatched beauty of their canyon home and much effort has been put forth to develop a lively tourist trade. The tribe as a whole never seems to be able to get excited about the idea at the same time, however, and progress is slow. Tourist cabins have been under construction for the past three years and may perhaps be finished next year.

Since World War I and even before, each year has seen a number of white visitors come into the canyon. Until about the last decade, most of these outsiders were photographers, writers, prospectors, geologists, National Park officials and even a few anthropologists. They either camped near the falls below the village or stayed in one of the government buildings.

In more recent years, a few tourists include a trip to Supai in their visit to Grand Canyon. There is a travel agent in Los Angeles who has made it part of a packaged tour and Hiking Clubs and Boy Scout Troops visit it in droves.

Image Number: 56825

Image Number: 56826

Although visitors are free to walk in if they please, they are encouraged to use saddle and pack horses, for they must be rented from the tribe at reasonable but sizable fees. The women have put new energy into their basket-making and though theirs are not the finest to be found in the southwest, they are attractive enough to induce more than one tourist to buy.

With Supai receiving more attention in travel and vacation magazines and with the tourist cabins nearing completion, it is possible that the Havasupais’ hope for more and more “paying guests” may be realized. When one visualizes this lovely spot as littered with beer bottles and gum wrappers, however, it is difficult to know whether to wish them good luck on their venture or not.

In comparing aboriginal Havasupai life with that of today, the most outstanding fact is that it’s just plain easier to live now. It’s easier for the children to survive once they are born and it’s easier for their mothers to bear them, since many of them go out to the hospital at Kingman for this purpose. It’s easier to keep healthy and easier to recover when one is ill. Preparing food is a simple task compared to what it was. Many household goods, with indispensable functions, are available in the store in improved form and more lasting quality. Keeping warm in the winter now requires half the time and less than half the worry for many families have kerosene or wood stoves. Probably most important of all is the fact that food is easier to get. This has resulted, somewhat, in Jess emphasis on the family as an economic unit-a condition which has been accompanied by a certain number of undesirable factors such as an increase in the number of divorces.

Even though the more readily available food supply has increased the amount of leisure time, there has been no corresponding elaboration of spare time activities or additional specialization. In the heat of early afternoon, however, one may still see the women gathering from all parts of the canyon by foot and horseback at some appointed place for their gambling session. This is an important daily event and the women, clad in their best dresses, congregate for poker, blackjack, Russian bank and plenty of gossip. Gambling is not limited to the women by any means, but they are the experts-they should be-they get more practice, for with them it is part of the daily routine and it has been for a long time. Before playing cards were introduced, intricate native games were played instead.

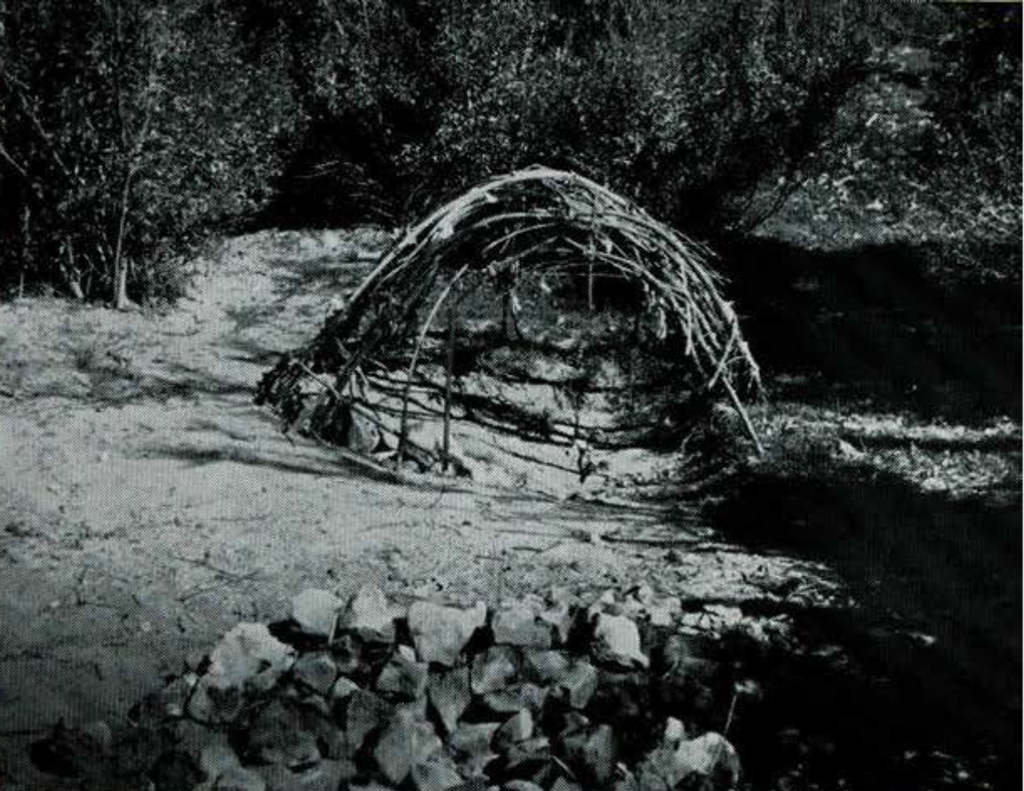

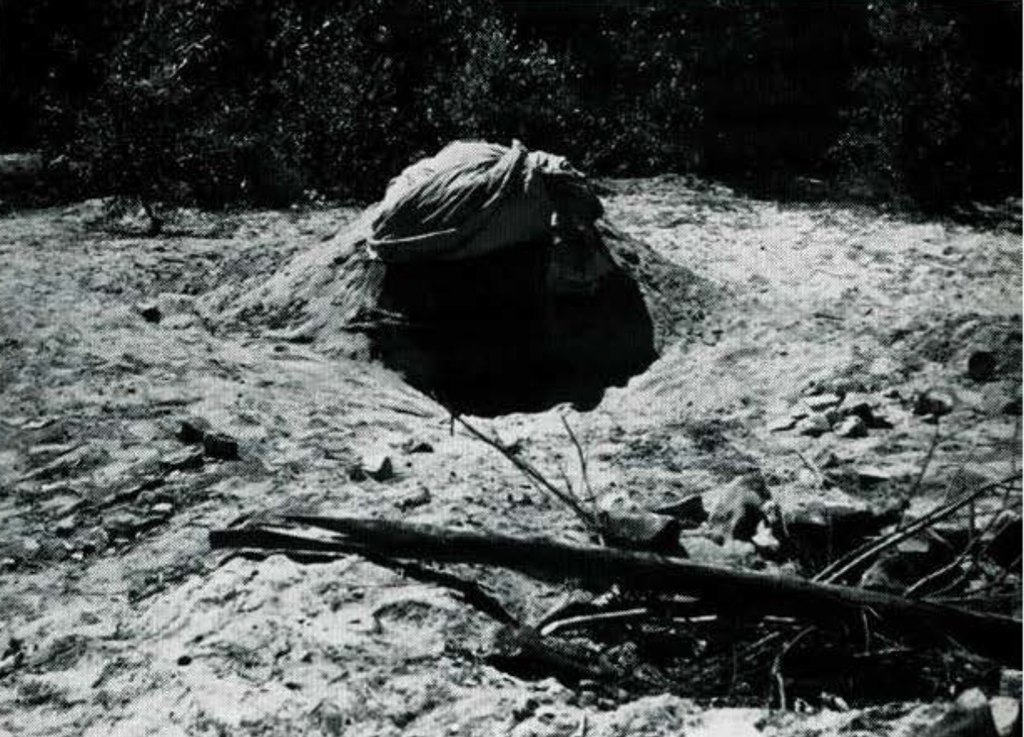

While the women gamble, most of the men take sweat-baths. This is their most important source of daily recreation. The sweat house is a small dome shaped structure over a shallow, circular pit. The frame is made of about a dozen slender poles set into the ground on one side of the pit and arched across to the other side. These are bound together where they cross and a number of horizontal braces are bent around them, leaving space for an entrance. This framework may be covered with blankets or brush and dirt.

Stones are heated outside and put into a small pit within the sweat house; then three or four men, clad in breech cloths, enter and close the blanket door. When water is sprinkled on the hot stones, it is instantly turned to steam. As the temperature proceeds upward to 140 or 150 degrees, special songs are sung which, in combination with the steam heat, are intended to effect cures of minor ailments. A full length sweat-bath consists of four steamings of about fifteen minutes in length, alternated with short intervals of rest in the shade. After the fourth steaming, it is customary to plunge into the nearby stream.

By the time the gambling and sweat-bathing are over, the sun is out of the canyon and then men and women drift slowly back to their camps. Even the children cease their endless play and turn their steps homeward as their stomachs tell them it is time for the final and heartiest meal of the day.

If, while the people of the canyon are ending another day, a visitor were walking among them, he might easily speculate that the future of the Havasupais will depend on the wisdom with which they confront the problems arising from the ever-increasing changes in an aboriginal way of life touched as yet but superficially by the Twentieth Century.

1 I wish to extend my thanks to the Anthropology Department of the University Pennsylvania for financial assistance with research in the summer of 1953. ↪