FOREWORD

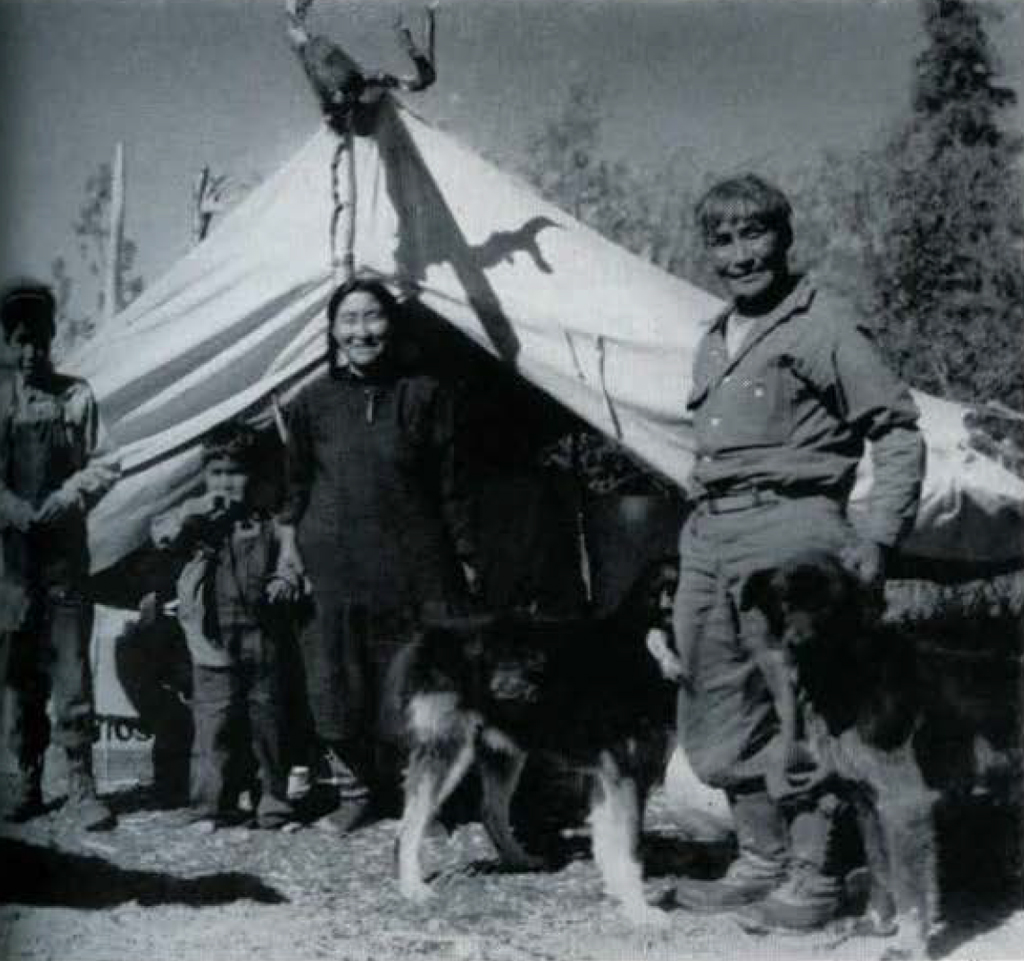

Three men and a woman were the chief narrators from whose accounts the following sketch is compounded. They were in their seventies and eighties during the years 1940, 1941, and 1947, when the author excavated sites along the upper Kobuk river. They had all reached maturity before the first Europeans arrived, and, unlike their younger kinsmen, they were able to distinguish aboriginal thought and practice sharply from the teachings of our traders, missionaries, and government agents. They talked of their own experiences, of their minor triumphs in hunting and love-making, and of their frustrations. The events here treated, though distilled from the lengthy accounts of all informants, are consistent for the upper Kobuk in the early l880’s, before the first explorers arrived.

The Kobuk river is about two hundred miles long. It heads among the steep slopes and sharp peaks of a rugged part of the Brooks Range of northern Alaska, gathering its many tumbling branches into a broad stream that Rows westward along the base of the mountains, just north of the Arctic Circle. Sloping off more gradually from the south is a series of rounded hills some of which have been swept free of vegetation and dotted with deserts of blowing sand.

In the headwaters of the river, people roam among trees that grow along the rivers and up mountain sides to an elevation of nearly two thousand feet. A thin veneer of green spruce and poplar on protected hillsides changes at the river bottom – along the frost-free stream margins – to a towering forest like that of more temperate regions. This is a place of lakes, some of them cut by little valley glaciers that existed briefly in a much earlier period. The river is normally crystal clear, bright objects appearing as white dots on the bottom of the deepest placid pools, and the rapids and waterfalls creating steely blue cauldrons in which the fish glint as they throw themselves around submerged boulders. The mountains are steep, culminating in blade-like ridges that bear a snow trimming well into the summer and may be dusted with snow at any season while encased in clouds.

The air is usually clear and dry in contrast to the fogs of the coast. The continuous summer sunlight encourages plant life to proliferate like that of a jungle. Bears wander along the slopes of the forest edge in search of berries, or wade in the rivers for fish, and moose make their customary rounds through the sheltering forest, escaping winged insect enemies by nearly submerging themselves in the rush-grown margins of lakes. Beaver dams break the smaller streams, and porcupines gnaw at the spruce bark. The animals are mainly those of the northern forest that stretches away thousands of miles to the east and south. Ducks and geese nest here during the summer, and loons splash and cry on the lakes.

A usual summer along the upper river is temperate, but on the occasional year heavy rains will fall-continuous drizzles for days and weeks at a time, until the river strains its margins and draws into itself the many- colored sediments, the dark swamp waters and clumps of grass and moss, in its surge to- wards the coast. A t times like these, the well-being of men and animals is greatly tried. And throughout most of the year the whole valley is firmly congealed beneath a layer of snow and ice.

SUMMER

It is late spring, or early summer. The ice has plunged away in its own melt water. The rivers are flowing free again. The air is filled with insect life, the sound of birds, and the delicious comfort of a high-Hying sun. A group of Kobuk people are arranged temporarily in early June along a bank of the river where the salmon will come by in great numbers. They have discarded much of the paraphernalia that goes with life during the cold season. The men have energetically begun to cut thin wands of willow for the tents and thick willow poles with crotches at the ends, for the support of caches and fish racks. The summer house is a half sphere made by inserting flexible willow poles into the ground at intervals about a circle, then drawing the tops of the poles together and interlacing them. A wide space is left between poles at the front of the hut, and the whole structure is then covered with spruce bark, which is laid on in overlapping strips and bound in place with rawhide line or the split roots of spruce trees.

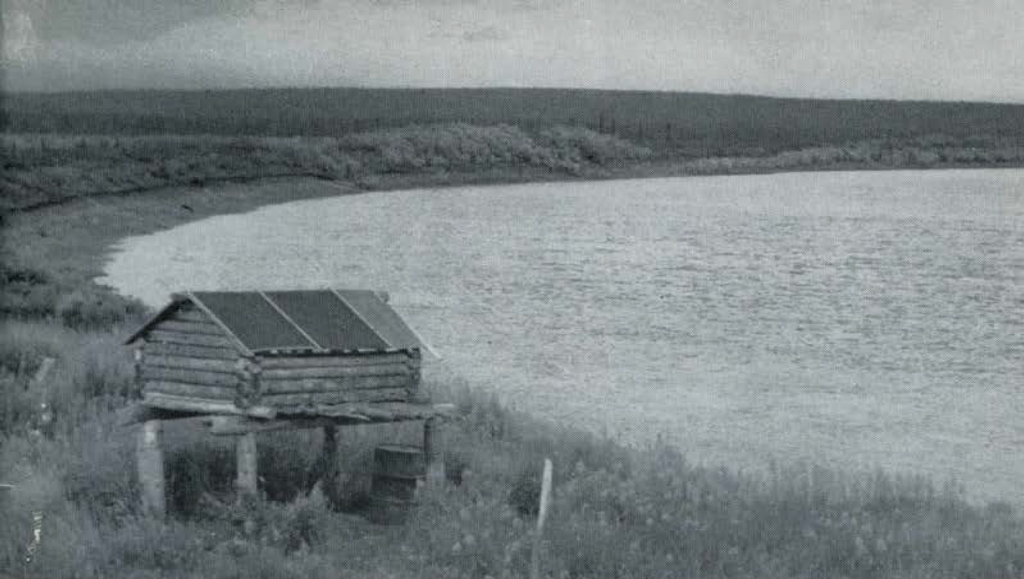

This is a good fishing place. The slower current at this bend of the river obliges salmon to swim close to the sandy beach. Along this bank at intervals of from only a few feet to many yards, stand the dome-shaped huts, like truncated mushrooms, a beaten path leading from one to the next along the river bank. Near each hut will soon rise a four-post structure, made of yellow poles from which the bark has been stripped, and supporting a platform on top. Covered by rain shields of bark or skin on these platforms will be stored most of the belongings of the people who live in the houses. The snowshoes that are no longer needed, extra wooden utensils, the dog harnesses, perhaps even the sledge itself, will be protected from gnawing animals and the prying hands of children upon these caches the floors of which stand as high as a man’s head.

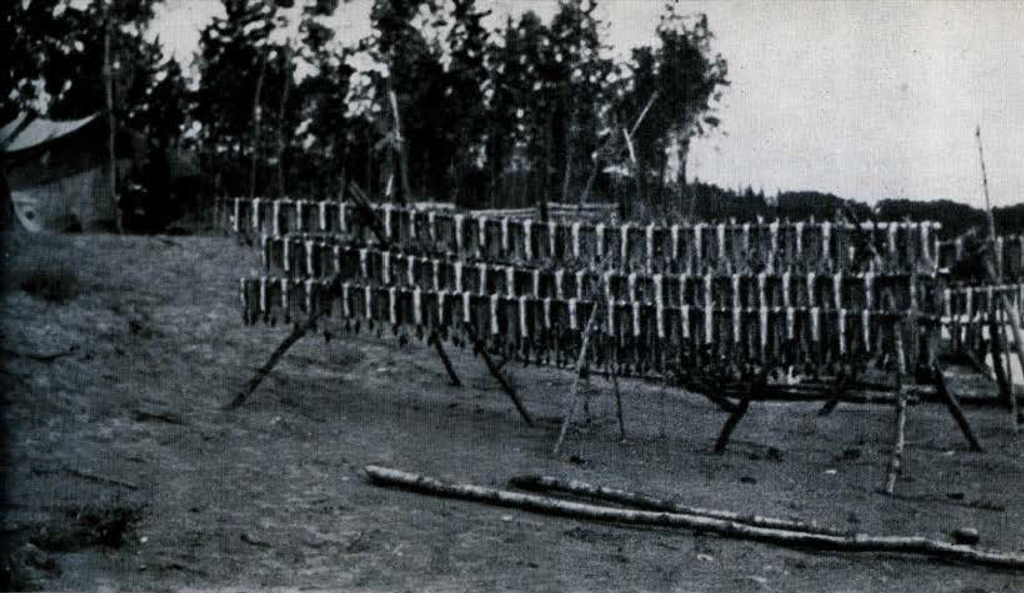

Stretching along one side of the tent, and paralleling the beach, as though to impress passers-by with the industry of the housewife, are built the fish racks, which will in the course of the summer, if all goes well, become heavily laden with the red strips that mean food and plenty for man and dogs during the coming months. The greatest compliment a man can pay his wife is to build her a tremendous fish rack two or three rows deep. She will be sure to try hard to fill them.

Near both the cache and the hut is an open fireplace, outlined by river boulders, around which are scattered the wooden tubs, buckets, and birch-bark baskets that a woman needs daily in preparing food and in rendering the products of hunting and gathering.

The house has no windows, nor has it a smoke hole. The doorway is likely to be hidden by a flap of skin, because the main function of the summer house is to turn the rain and repel the mosquitos. A darkened hut is somewhat baffling to the flying pests that form a particular hazard of Arctic life. At the height of a mosquito attack on a still, humid day before a thunderstorm, one can only duck into the low-roofed hut and cover himself as much as possible with clothing to secure respite. Often a little fire is made in the hut, the smoke creating a haze in which it is barely possible for the occupants to breathe, but which successfully stuns the mosquitos that find their way in.

This is a woman’s village. The men remain in camp only long enough to make sure that the women are adequately provided with shelter, the provisions for drying fish, and the odds and ends of equipment that only a man is supposed to make. Some time in June, and still before the salmon have begun to appear, the men split up into small groups and leave for the mountains. A man and his half-grown sons will go together, expecting to meet friends along the way. A half-dozen other men will choose to hunt in a certain vicinity, and will josh with one another as they prepare to leave the females and youngest: boys of their family. “Take care with the women,” a man will say to his four-year-old toddler, “watch out for them in summer time!”

The men depart in their little groups, equipped with only the scantiest of material. It would be considered improper and spiritually dangerous to carry on one’s back a large amount of equipment. Each man has received from his woman a pair of new, short boots and an extra sole of heavy sealskin if this has been secured in time from the coast. He wears a pair of short trousers, terminating above the knees, and held at the top by a rawhide belt with a carved wooden or ivory buckle. A head band holds his long, black hair in place, and, other than these, his goods are on his back. The sinew-backed bow is carried in one hand. A dozen arrows lie in a fish-skin quiver over one shoulder, and a small back pack suspended from the shoulders contains the few commodities that he cannot do without – his tobacco and pipe, perhaps fire-making equipment in a water-tight container, a knife or two and an extra bit of Siberian trade metal with which he can repair his knife.

The men travel light, heading at once for the ridges rather than the streams. They climb up the slopes to the north, emerging from the obscuring thickets and forest into the open air of alpine meadows and slopes. Here, along many miles of the highlands, they will spend the summer, striving to get the special goods that will be either used during the coming winter or bulked together as currency to be passed along through one of the native traders in exchange for materials from the coast.

The hunters take a great deal of summer leisure while their wives are working steadily elsewhere. They set snares for mountain sheep far up among the crags, retiring to lower elevations for their evening camp. Day after day they climb to the high mountains and back again, inspecting traps and snares and remaining continually as well on the alert for animals that can be stalked and shot with an arrow. Snares are set between boulders where sheep or caribou normally file, and rock traps mark the entrance to a marmot hole, a slab of stone falling when triggered by the nose of the cautious animal. Once in a while a barren grounds grizzly mistakes a man for a caribou and approaches dangerously close. Only the best hunters dare to let fly an arrow at a grizzly, and it is best to do this in company with other sure marksmen. Also to be found in the high country are the solitary caribou that feed at wide intervals – a doe with fawn, a buck alone – wary and alert, yet curious, too. A hunter takes advantage of the curiosity of the caribou, encouraging them by high whistlings and squeakings to approach in an ever-narrowing circle until the fatal shot can be fired.

The men meet in groups in the evening and talk things over. They plan trips and think up new songs and patterns of dance for ceremonial occasions of the coming winter. They pass along to one another the most intimate details of those parts of the country in which each family has resided during the previous year. Through this means they exchange ideas and knowledge over a vast area during the open months of the summer, for along the mountain ridges one meets sooner or later his male relatives as well as others with whom he is out of touch during most of a normal year.

Food is abundant. The young of caribou and sheep may be killed in the early summer for their prime soft skins to be used as inner garments and fancy trimming. One eats as much as he can of the meat of these animals. Only their skins are saved, for it would be impracticable to transport quantities of dried meat out of the mountains and down to the family camps. The skins are properly cached on high platforms at the upper edge of the forest where poles may be cut, and mountain sheep horns are carefully hidden from the gnawing teeth of rodents. Antler of choice caribou is cut into proper lengths and packed away among the dried skins that will be softened and tanned later for use during the winter in the making of clothing, tents, and sleeping bags. The horn and antler will be used for whittling and carving the hard and resilient parts of weapons, containers, and movable devices. The sinew, which is saved with the greatest care, will be needed by the women for their fine sewing. The men feel no reticence about taking their leisure at length. They know that the work of the hunter is the work of a moment-the well placed arrow-the leap and sudden death of the pierced animal-the speedy removal of its vital skin and sinew. A man’s work is quickly done. He needs long rest and quiet to resist the dangers that go with the taking of the lives of other creatures. One sleeps and eats as much as he wants, and makes magical observations around the campfire in the night sunlight.

Back at the river camp, in the meantime, the women are by no means idle. The final mending of the nets is done by women working in crews-those who will seine together are likely to stretch their particular willow-bark net on a dry strip of gravel or sand and set about mending the weak spots, dexterously

threading their netting needles and mesh gauges. The mesh gauge is made of a strip of antler whittled into a handle to fit the small hand of a woman, at one end of which is a wide, key-like projection to be fitted between knots of the fish net to give the required spacing. Some mesh gauges are double-ended, the opposite end having the gauge required for smaller fish than salmon. The netting needle is a long, flat reel of antler or wood, the ends of which are double-horned, the horns bending in towards each other, but not quite touching. The net is about seventy-five feet long and four feet wide. At its lower margin are attached sections of caribou antler that have been perforated at either end and strung parallel to the heavy bottom line of the net, while strung similarly to the top line of the net are oval floats made of poplar wood or thick and very light cottonwood bark. At either end of the long net is a spruce pole that acts as a stretcher. The net is made of the inner bark of willows, a material collected in the spring, when it is twisted and wound as balls to be used as needed throughout the year.

The women who are camped together are likely to be closely related. A mother and her daughters will make a special effort to fish together in the summer, and the tents that make up the women’s village are more often than not those of families related through the maternal line.

While some members of the family mend nets, others take digging sticks and hunt for polygonum roots and tubers along the banks of the river and inland on the margins of ponds. Willow leaves are gathered for food early in the season, as is also wild rhubarb and a variety of other green plants. Some greens are eaten raw with fish oil, while others are boiled into the stew with fish or meat. A woman usually also has a string of snares along a neighboring pond, where she secures now and then a small duck. Bird’s eggs can be gathered in nearby places. Children often employ themselves with egg collecting excursions.

Back in camp there is the occasional uproar of dogs when one of them commences to cry for food or to howl from boredom. The dogs are tied to stakes in the vicinity of the house, and each requires a wide area in which to rotate about his stake. A dog is not tied with thongs, for he would quickly chew through them, but is pivoted from his stake by a forked pole, the crotch of which fits around his neck. The dog is thus able to run round and round his stake, like a mill horse, but is unable to break loose and harm the many items of meat, thong and hide that lie about a camp.

When a dog commences to howl, all of the dogs along the river bank join in, and there is the high music of myriad voices attempting, but failing utterly, to reach a common high note. Far away along the river new dog cries will be heard, announcing the presence of other camps.

Children play at teasing the dogs, and they amuse themselves in groups mainly without recourse to their mothers, aunts, and grandmothers except at meal times or for the direct necessities. Little bands of children trot along the bank of the river, dragging model canoes that their fathers have made for them, or pretending to fish with miniature nets or bent poles, or simply wading in the delightful water and sand. Now and then they throw off the small items of clothing, if indeed they wear any, and splash into the river for an interval of ducking and dog-paddling.

Out again, and tarrying in the smoke of a smudge to dis- courage the mosquitoes, the children are soon off to their imitative games, which include the building of houses and caches, and other activities that they have observed of their parents. Women seldom call out to children, and never scold them, unless for stumbling into the stretched fish net. Children are autonomous. They make their own rules, and by self-censure and ridicule manage their own affairs with great harmony.

During this early part of the summer, the women have set short gill nets in eddies at the mouths of small streams, and from these they secure a few pickerel each day, along with an occasional whitefish and grayling.

The anticipation begins to mount towards the longest days of the year, when the sun never quite sets in the north, and when the first searching salmon are seen gliding through the clear water offshore. The women make no effort to catch these avant-couriers. They are now organized into a team, and the team has a definite leader. This leader is likely to be the oldest woman present, if she is also wise. Perhaps she takes no active hand in the cutting of the fish, for she may be feeble and still an able captain of the crew. Now the women remain close to the seining area in the month of July, and their leader is forever vigilant. This woman stands on a high point of the beach hour after hour, looking far downstream. She is watching for the telltale ripples, not evident to a newcomer or to a younger woman, that will tell her beyond a doubt that the great families of salmon have at last decided to visit this part of the river.

The moment of fierce activity has arrived. The old woman gives a hoarse cry of command. All of the women spring to their positions along the beach, dropping whatever they happen to be doing at the moment. A baby squalls where it has been hastily placed in a pile of leaves. A basket falls to the ground, scattering edible roots. Two women run swiftly to a birch bark canoe that has been dampened from time to time and is pulled only half out of the water at the river bank. In this canoe lies the seine, carefully folded. The stronger woman takes up her paddle and balances quickly into the stern seat. Her companion pushes off the canoe, jumps in, and begins to pay out the net. Paddling only slightly against the current, and very quickly out towards the center of the stream, the women leave a splash of net astern of them. The swift current swings their boat rapidly downstream, and then the paddling ceases for a moment, while the remainder of the net is cleared of the gunwales of the frail craft. Then the paddler exerts herself to reach shore quickly, while the other woman grasps the stretcher at her end of the net.

Speedily the boat is beached again, and these two women pull for all they are worth to drag the line of sinkers nearest them up onto the sand of the previously clean-swept beach. All along the beach women and children are dashing into the water to grasp the bottom of the net as quickly as possible and drag it towards them on the shore. The salmon have been trapped. They create a mighty churning and whitening of the water as they are brought out of the depths and onto the shelf of sand from which they are not likely to escape. The women now begin to throw the salmon singly as far up on the bank as they can, for the combined weight of the fish is so great that the net would tear if further strained. It must be cleared of fish while it is still in the water. There may be several hundred salmon, most of them two and a half or three feet in length, all silver and pink, and strongly resisting this effort to remove them from their element. Those women and children who can be spared now take short wooden clubs and run along beating each salmon over the head. The killing proceeds at a maniacal pace, amid cries of excitement, until all of the salmon have ceased their violent wriggling.

No doubt there is an old man, or perhaps more than one, who has been so crippled that he cannot go out hunting with the other men, and who is obliged to remain in the vicinity of the women during the summer. He is likely to be a temporary misogynist, who lives alone, but who cannot resist sitting on the river bank and watching the activity. He may even forget himself so far as to make some critical remark about the way in which the women are going about their work. If he does he will be roundly tongue-lashed in return, if he is not subjected to a token stoning. His only work in the salmon fishing is that of wielding one of the killing clubs. Other roles that he might play in the fishing would be regarded as not only ridiculous, but as dangerous to people and insulting to salmon.

Now the women transfer the beached fish to large circular depressions that they have prepared ahead and lined with fresh willow leaves. The fish are thrown into the pits and now and then covered with a layer of leafy branches until the pits are completely filled. A final coating of leaves is placed over the whole cache until it is time to prepare the fish for drying.

While the salmon are running, three or four quick hauls may be made, but no more. The net should not be wetted too often, or it will become slack and break. It must be dried thoroughly between times. The fish pits should be filled, if possible, and every woman should have enough work provided for her to last for some time.

The cutting of salmon begins soon after the catch is made. One or more women kneel at the margin of a pit in which the salmon are stored. Each woman has within reach a large, wooden-sided tub into which she throws the intestines and other organs, another similar tub into which are tossed the severed heads, and a pile of fresh leaves upon which is spread the remainder of the fish before it is placed upon the racks. If the mosquitoes are bad, she also has a smudge upwind so that she is shielded by a constant billow of acrid smoke of rotten cottonwood. One cannot forget the knife in one’s hand when a mosquito bites the face, or the swat may be disastrous. A woman takes her ulu, the knife with a halfmoon-shaped blade, and wielding it deftly, first chops off the head over a block of wood, splits down the belly and removes the internal organs, then turns the fish over and splits twice along the sides of the backbone, separating meat from ribs towards the tail. The three strips then are attached at the tail region only, and the whole can be placed over the pole of a drying rack in such a way as to expose the red flesh to the drying air and sunshine.

When a large number of salmon have been cut, and the pit emptied by one or more women, the hanging begins. The fish racks now receive a burden of split fish that are exposed to the best drying conditions. The heads are taken to a spot along the river bank, where they are buried in leaf-lined caches within the sand and gravel. They will be left here until fall, when they will be dug up as a special, fine, cheese-like dish to be served to the returning men. The intestines are gathered in tubs to be finally boiled with hot rocks to render the precious fish oil that takes the place here of the seal oil used by people of the coast.

The salmon is used in its entirety. Nothing is wasted. The bones and tails and fins become dog food when people have finished with them. But in taking the salmon, the women are most careful to be sure that nothing is done to offend the fish so that they will not return freely year after year. Various observations must be carried out carefully to effect this. And the uses to which the fish are put are uses that are full of respect.

A young woman who is pregnant has come near to the time of childbirth before the height of the fishing season. When it is decided by her older advisers that her time is near, she prevails upon the old man to exert himself to prepare a place for her away from the village. He goes out into a dense part of the spruce forest, well away from the sights and sounds of the river bank, where there is no danger that either the fish or the children will intrude upon the silence. Here he throws together a tepee of spruce saplings. This is called a milyuk-a conical structure in which the branches will cause water to drip outward, and which can be inhabited for a short time with the minimum of effort.

When he has completed the milyuk, the old man reports back to the pregnant woman, who thanks him and learns directions to the hut. When she feels the first rhythms of childbirth, she retires to her forest concealment, and there, without the aid of a midwife, and away from the sounds of humanity, she gives birth to her child. Kneeling and working her body with her hands inside the shelter of the hut she makes her own delivery, and cuts the cord with a knife of obsidian that she has obtained for this purpose. She bathes the infant and herself in a nearby stream, and returns to the seclusion of her hut. Here she must remain for four full. days, careful not to make her presence known to individuals who may inadvertently wander past, for she is kongok.

When asking for a translation into English of this word, kongok, the best one can learn is that it is a kind of “poison.” It is associated with the loss of blood, though this is not always the case, and the person or thing that has become kongok is to be avoided at all cost.

The new mother’s only visitors during this time will be an old woman or so who is more or less immune to kongok by virtue of her age. At the end of the fourth day, through which she has carefully watched her diet, avoiding certain foods, she returns to her home on the river bank, presents her child to her family and friends. Now she goes about her work as usual. Although a child born in winter is carried within the parka of a mother, held up by her belt, this is not necessary during the warm summer months, when the mother can practically leave off this warm clothing and place the child in a cradle of skins or birch bark that she can keep by her side.

As the summer goes along, the fish racks normally begin to fill out to a point of satisfaction for those who will support their dogs and themselves on dried fish during some of the cold months. A bad season can seriously strain the resources of a river group. When the sun and air have sufficiently dried the hanging salmon, the fish are removed from the outdoor rack and placed upon the platform caches under waterproof covers.

August is the height of the salmon season. Now great swarms of fish fight their way to the headwaters to spawn. Already the males are dying far up the river and are floating back down, littering the shores with their grotesque, long-toothed, emaciated skeletons. The women who seine do not attempt to take fish day after day, however. As soon as the cache holes that have been prepared are filled, the seining is over until every woman has cleaned every fish. The salmon may go by in hundreds of thousands, and no one will so much as glance their way. There will be no further watching of the currents until it is time to seine for another lot. Because of this patterning of the woman’s fishing, there can never be too serious inroads on the fish population. But people can go hungry, if only because when the group is ready again to seine, the fish may not choose to come by. Or perhaps it is stormy during the period of the largest fish run. One does not seine in stormy weather. It would be neither a practical process nor a spiritual means of satisfying the salmon.

August is also berry picking time. The women take every opportunity to go out on the slopes of the hills with birch bark baskets and beating sticks to secure quantities of blueberries, some of which can be preserved in oil, some eaten at once, and some allowed to half dry for winter use. Other berries, such as cranberries, black and red currents, and yellow cloudberries, are eaten as they ripen but are seldom kept for any length of time. The woman gathering blueberries holds her basket of folded and sewn bark under the berry bushes and beats vigorously as she moves along, quickly filling it to the brim with berries and leaves. The leaves are seldom carefully removed when the berries are eaten. In her visits to the berrying grounds, she often finds that the black bears have been ahead of her, stripping the bushes of berries, leaves and twigs in their eagerness, and pawing up quantities of earth on the slopes. Bears and women have a great deal in common, she remembers.

AUTUMN

Towards the end of the summer there is likely to be some atmospheric violence as a result of the coastal storms. Still, quiet, and clear though the upper river usually is throughout the summer, it now becomes wind-whipped and soaked with rain. The women and children huddle long hours in their tents, covering themselves with skins and venturing out to build difficult fires behind windbreaks for only the necessary cooking. These are dismal occasions. The men are gone who could liven the intervals with story telling and clowning, but everyone listens eagerly for long hours at a time to the stories that old women know and repeat-tales of the heroic past, legends about the beginnings of men and other creatures, and simple tales calculated to hold the listeners temporarily in suspense.

Up in the mountains the storms have also put an end to leisurely entertainment and persistent hunting. The men retire to the forest edge, and there build themselves large fires in the shelter of rocks, or behind windbreaks of spruce cut with the branches on, and there wait out the storm in dripping half-comfort, eating too much, and telling the same stories over again.

Some time in the late summer, the men in the high country observe certain signs. Frost begins to come towards midnight. There are several hours of darkness in place of the midnight sun. And wildfowl are beginning to move to the lower slopes and ponds. This is a signal to gather up one’s choicest furs into a huge back pack and return to the bank of the large river. Often the men who belong to a particular camp have joined one another by prearrangement, and have transported their skins and other products of the hunt to the nearest small stream that flows into a tributary of the big river. Here they pile up their goods and make rafts. If the stream is very shallow and difficult, a man builds a raft of four or five logs for himself alone. He lashes the small ends together as the bow, secures the other end by means of lashing and crosspieces, loads on his furs, and, straddling the raft, poling in deeper pools, half walking at times, and pushing through shoals. reaches at last a point where his raft floats free. Here he is joined by another, and another, of his hunting partners, and they unite their rafts, binding them together into one large craft on which it is possible to run about, or sleep, or cook a meal, while floating leisurely toward the place where the women are camped.

Finally the raft draws up before the river bank where the fish racks are now full.

There is no shouting and waving of hands. Instead, both men and women display reserve at a time like this. The men and boys slowly unload their rafts in front of their separate houses, the women going about their outdoor work as though nothing of particular interest is taking place. Now the men walk into camp. Slowly the reserve is broken, and within a short time the camp comes alive with the happy chatter of families reunited after the long summer.

Autumn is a splendid time of the year along the upper Kobuk. Mosquitoes have nearly disappeared, the air is crisp and clear, and waterfowl are gathering in large flocks tarrying for a few more days before flying south. Black bears are fat, and their cubs are grown and already looking for places in which to hibernate.

The people who now are united as families in a temporary camp on the river bank watch for signs of cold weather such as may bring the caribou down across the mountains to their customary crossings. Until the signs appear, this family is at rest. The salmon have now been caught and dried and cached away for the winter. Skins that will be used have been placed where they will not come to harm from bears, foxes, or ravens, and sufficient fall clothing is already made and in readiness for the next journey. During these warm days and pleasant nights, the community indulges in all kinds of group activities. There will be a drum dance on the river bank, beginning with the inspiration of a solitary drummer who draws in another man or two who tighten the membranes to their drum frames and begin to join him in the rhythm. Soon a woman is inspired by the music to a point where she steps in front of the drummers and follows their rhythm with swaying motions of her head and body. Now thrusting the head and hands sidewise in one direction and now in another, all in close harmony with the drumming, men and women begin to interpret experiences of their own, or the whole group will feel inspired to dance out a song it knows well, a song that relates to some experiences of the years past or simply to some set of magical words whose meaning is not exactly known. If there is an occasion to be celebrated, this is the time. Perhaps a child is to be named. It is learned at last, definitely, who it is that has been reborn, and the naming takes place with dancing and the music of drums. Or a small boy has killed his first game-a mouse which he has stalked with his club and overpowered. The whole group gathers about and seriously praises the boy and submits him to magical rubbing and songs. An old man steps forward and praises the father of this boy, saying what a fine hunter the father is, and pointing to the boy as an example of what one can expect in the future of this distinguished family.

There is food in plenty. The choice sheep meat has been brought down by the men, and there are marrow bones of caribou, and quantities of rich, fat fish to be eaten with berries and oil. Now is the time, some one remembers, to dig up the salmon heads. This rich fare has now reduced itself, under the soft summer sun, to a cheesy consistency in which can be rarely discerned a bone or a scale that is hard to chew. This is a rare treat, and worth waiting for a whole year!

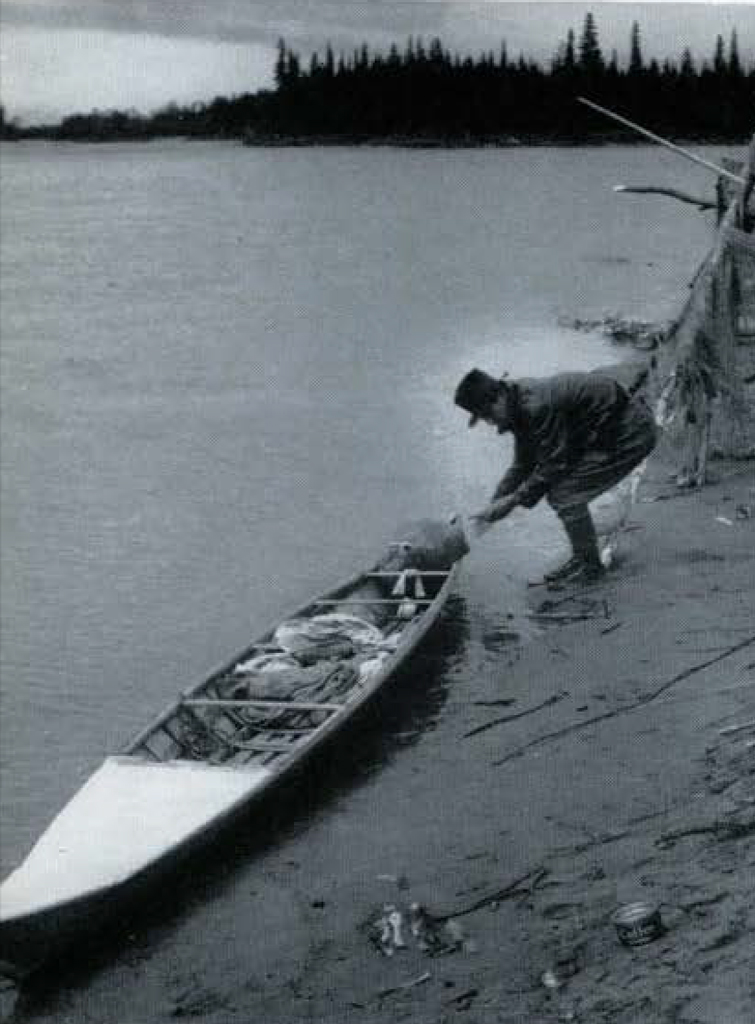

The unaccustomed leisure and indolence are soon over, however. Both men and women begin to prepare for a journey. They patch the bark canoes, make sure the caches that will contain their precious goods are safe from bears and wolverenes, and manufacture the last items that will be needed on the journey. The dogs are well fed after a summer of neglect, and they are anxious to be off on a journey that they seem to sense. Then, one morning, the whole community breaks camp. Gear is piled high in the family canoes. Women and children go aboard. Dogs are brought in last, to be tapped vigorously if they need reminding that they are to lie still on top of the load. A man takes his place as steersman. Other men and boys paddle the small bark kayaks that will be needed in the caribou hunt.

Off goes the small flotilla, out across the river to the shoal water of the opposite side, women paddling with the steersman, until the current becomes, strong. At this stage a landing is made, and the dogs are taken ashore, harnessed, and attached to the end of a long lead line. The dogs now trot along shore, pulling the boats slowly upstream. When they come to an impenetrable bit of forest on a cut bank, the dogs halt, the people pull the boat ashore, take the dogs aboard and paddle to another long beach along which the dog power can be used again. By this means, alternately paddling, poling, and being pulled by a team of clogs, family after family arrives at a prearranged hunting place, somewhere in the upper reaches of the river, where the mountains come close to the main stream, and where lakes lie between ridges to the north.

Working slowly up a difficult tributary stream, the boats reach a camping place in spruce forest at the outlet of a lake which is several miles long. Men draw the boats ashore and pitch a camp that will last for perhaps half a month. The tents this time are like those of the river bank camps, hemispherical in form, but they are covered with blankets of skins instead of with bark, and they are provided with smoke holes in the top. It is now that part of the year when an indoor fire is a pleasure if not an absolute necessity. The skins of the tent may be last year’s skins from which the hair has been removed. Some twelve or thirteen caribou skins sewn together form the large cover that fits an ordinary family tent frame. In this echellek, with a small fire in the center and the flickering light playing upon the translucent walls, the tents become shadow shows, each telling its own story. A crisp, new season of ice is about to begin.

The caribou have already begun to cross the river at this point. The trails of dozens of the creatures have broken the new vegetation from the top of the ridge above camp. Early in the morning, most of the group climb the ridge to a more or less level plateau nearly a thousand feet above the lake. They see the stone cairns that have stood here from ancient times. These cairns are in a line leading to a steep slope falling off towards the lake. A second line of cairns comes in at an angle, converging on the first. Women and children walk far out along the line of cairns, some of them as much as two or three miles from camp, and station themselves at intervals between the piles of stones to add a human element to the human-like component that is expressed in the cairns themselves. These individuals are not armed, nor are those who remain closer to the brow of the ridge. It is not necessary to kill the caribou on top of the plateau. One slaughters only close to home!

Now in the distance there appears a herd of caribou. Close-packed they flow along over the rolling surface of the mountain plain, remaining close together as though held by some magnetism into a compact herd. A leader appears for a while and then he blends with the herd, and another heavy-antlered male appears in the lead in another place. The movement is fluid, and without the direction of wisdom, yet inexorably the caribou approach the two lines of cairns and follow along between them. If they hesitate, or begin to straggle, those people who are at the outer end of the line raise themselves up and wave their arms to urge the herd onward and into the narrowing funnel. People at intervals keep the herd on the move, discouraging grazing on the way, until the animals, a hundred or more, find themselves a narrowing herd between converging lines of cairns and people. At last they are encouraged by the shouting and leaping women and children to dash ahead at great speed, the whole herd now throwing themselves into the funnel from which it emerges a thin line that trickles over the edge of the slope and half falls down the bank and into the lake. The slope is steeper than caribou would normally choose, and some of them are disabled and fall as they throw their legs forward to break the speed. When they come to the lake they splash in and begin to swim towards the opposite shore. It is here that the killing begins. Men in kayaks dart out from shore, wielding short-handled spears. Other men on shore shoot the animals repeatedly before they have had a chance to submerge themselves. Once in the water, the caribou are easy prey for a man in a canoe who has but to propel his vessel swiftly towards the head of an animal, plunge his spear or swing his club and be off to the next. The blue water soon streaks with red. The struggling, drowning caribou are slowly borne by the lake mouth current toward exactly the spot where they are intended to be cut up and dressed. There is a great cry from all of the people who take part in the hunt. The caribou are terrified as they continue to drop over the bank. Children run to the animals that lie dead or seriously wounded and put their mouths to the wounds to drink the gushing, warm blood. Soon the whole herd has passed from the hilltop down the slope and into the water, and those that have escaped are allowed to go their way without further molestation. A survey is made to learn whether or not these are all of the animals that are presently needed. If there seem to be enough to occupy the men and women for a reasonable length of time no further effort is made to divert the caribou that continue to move out of the mountains toward this crossing and into the ambush. Hundreds and thousands of caribou may now continue to cross the river without bother, pausing to look at the people who are camped at the foot of the ridge, running a bit, stopping again to look, but untouched so long as the people have work left to do.

The camp is full of excitement while the cutting is in progress. Men and women work together on the task of separating the carcasses from their skins while they are still warm. Like the salmon, the caribou is useful from the tip of its antlers to its splayed-out hoofs. The skins are carefully removed, stretched, and partly dried. Some are worked with scrapers by the women to remove as much as possible of the fatty tissue and blood vessels so that the skins may be later softened for use as clothing and tent covers. Some of the skins are simply dried hard to serve as underbedding, floor covering, and the like. The sun is less effective at this season than it has been earlier, but it can still reduce strips of caribou meat and the flesh left on ribs and bones to a black, hard jerky that will keep until the permanent frost comes to preserve all meat for the winter.

Antlers are chosen for the making of adz handles, tent pegs, drum rims and a hundred other devices and parts. The sinew is removed for thread. The long bones are cracked for the marrow, and then further cracked into splinters and boiled into a delicious soup. The heavy back fat is carefully stored away as a source of vitally needed winter food.

The air is crisp. Children don their parkas and trousers and boots in the early morning, though they remove them later when the sun climbs higher. The grouping of people at the caribou crossing is likely to be somewhat different from that of the summer fishing place. While the compatibility of a fishing team may depend upon a female line of kinship, it is more likely that the hunting patterns, in the control of the men, involve one’s father’s relatives and friends. The caribou hunt therefore affords a good chance for young people to meet and mate. In place of the cousins on the mother’s side, the children get to know more distant relatives and those to whom one is not really related at all. Those who are not married have an opportunity to form temporary attachments that take them away into secret places. If the camp is large, and the tents are scattered through the forest edge and through the willow brush for a considerable distance, it may be that sub-groups split off each with its particular traditions and reserve. A young man who has proven himself capable of providing food for a wife-who has killed a bear or so, and is proficient in the kayak and in setting snares for the summer hunt, may feel that he has reached the age at which he deserves a wife. He has been hinting at this to his mother for some time, and bis mother has felt the weight of her obligations. She has already begun to talk to women who are not directly related to her about their daughters. All of this proceeds in a most circumspect way.

The boy in the meantime has made a selection of his own. She is the youngest daughter of an able and respected hunter. Hee and the girl have had occasion to know each other a time or so since she has undergone her first adolescence confinement. They have reached an agreement among themselves, but the girl’s father is violently opposed to his daughter’s marriage. He has made loud and apoplectic gestures towards the youth in prospect.

The boy has no father at the moment, and this is a great handicap to him. His mother will find a husband eventually, but just now there is no one with a strong voice to speak for him. The mother is incapable of making the match by herself. She has been repulsed a time or so, and she no longer dares take up her son’s suit.

The youth goes to a relative, an uncle who is also camped at the caribou crossing. The uncle and the boy’s older brothers agree to a plan of action. They advise the boy to arm himself as they are and follow closely a formula that they have devised.

Early one morning towards the end of the caribou season, when enough skins and meat have been prepared to satisfy nearly everyone, and when there is leisure before the next nomadic move, this youth and his male relatives launch the large canoe that belongs to the boy’s mother, and paddle as though bent on a dangerous mission silently along the edge of the lake to the spot where they see the tent of the girl’s family. The visitors beach their boat quickly, but not without noises of alarm, and, half-crouching, place arrows to their bow strings. This camp is now alive with activity. The male members of the little group of tents in this spot have armed themselves with bows, spears and clubs, and return menacing gesture for gesture. There now begins a chanting on the side of the visitors, interspersed by insulting cries from both parties, who now appear ready to let fly their arrows at close range. It seems that violence is inevitable. Before an arrow is actually loosed, or a spear thrown, however, the uncle of the youth who wants to be married signals to his protege, who then runs around through the willow brush to the back of the tent where he knows his intended wife makes her bed. The women are gathered in this tent. \¥hen the skin cover is abruptly thrown up at the rear, and the youth takes the arm of the girl and draws her roughly with him, the women raise a mighty clatter of indignation.

In spite of the alarm and even though the sides are essentially even, and the women could undoubtedly impede the kidnap, the youth is able to lead the girl after him along a devious trail through the brush to the spot where the boat has been beached. The two of them launch the boat quickly, take up their paddles and speed away towards the outlet of the lake.

This is all the formality of marriage that is necessary. The boy and girl will paddle away down the river to where the boy’s relatives have belongings, and there they will begin to build a house of their own and set themselves up for the winter with the aid of relatives who will later return to that part of the river.

In the meantime, back at the caribou camp, the shouting and tumult lasts only until it is clear that the girl has been kidnaped. No further attempt is made to impede the bride capture, and both sides, seeing that there is no longer need for threat, begin to drop their reserve, and soon find themselves gathered about a huge feast, which somehow has been prepared in advance, as though in anticipation of a great occasion. The two families are now closely bound to each other, and will remain so as long as the marriage lasts.

The people at the caribou camp have now prepared as many skins as they will need during the year. A sufficiency of meat is drying on the racks, or is slowly freezing as the sun loses its power, and the ponds are sometimes coated in the early morning with a substantial film of ice. The time is late September or early October-a time when it is wise to drift down to the autumn fishing place. The freezing up of the river is normally a gradual process, but it does no harm to reach the fall camp early, even though it means a regretful ending to the pleasant associations of a caribou camp.

WINTER

Now the small family is paramount again. Uncles and relatives by marriage part company with their kindred. Bantering with each other, and at the same time half arranging meetings that will take place during the coming year, members of the separate families take to their own rafts and canoes, and drift away from the hunting place to float, or leisurely paddle to a not too remote bend of the big river.

The move away from the Kobuk headwaters or smaller tributaries leads each family now to a broad section of the river, where it has been customary for a man and his fathers before him to build a winter house. The house must be rebuilt each year. This is not because the old one is uninhabitable, but for a number of reasons that have to do with the well being of people and the animals they hunt. A former house is like an old shell of one’s self. The house building place is not determined by an exact site, but by the section of the river to which the family has fishing rights or understandings with neighbors. The house will be built where the soil is sandy and well drained. It will be close to the bank of the river, and above all, its entrance will look out upon that part of the river where fish traps will be set.

A man and his wife, with their dependents, scout out a likely spot for the new house shortly after they have landed from the hunting expedition. Perhaps it is convenient to build very near to a cache where one’s wintertime belongings have been stored. If not, a new cache is first built to protect the more perishable stores of the family. It is beginning to freeze solidly at night now. The ponds are iced over beyond the power of midday sun to dispel. The man tests the ground day after day to learn how deeply the new frost has penetrated. Camped behind a simple lean-to or in a temporary echellek, the family spends most of its time gathering driftwood logs from the river bank to be used in the walls and roof of the house. If last year’s house is near by, the poles from its roof and half-fallen walls are uprooted and taken to the new site, for it is felt that no particular harm can come from using old material if the old house is avoided as a unit. When house building material is piled up near the place where the excavation is to be made, the man and his wife repair to a muskeg area, or a hillside, where small spruces grow slowly and with dense, close-held foliage. These small trees are cut one after the other and transported to the river bank. They need be little more than a man’s height if their branches are dense. They will be used in constructing the “fish fence,” which is the principal means of making a living during the coming weeks.

The geese have now gone south. The last stragglers of the scaups and widgeons are still skirting the shore ice in search of food in the eddies, but other summer birds have gone. If snow has not yet covered the ground, the family finds it interesting and highly amusing to hunt for snowshoe rabbits and ptarmigan with blunt-ended arrows. The snowshoe rabbits have anticipated the winter by turning white. Until the snow comes they are without means of concealing themselves from human enemies, and the ptarmigan are also shifting from their brown and gray summer feathers to pure white. These creatures that are accustomed to keeping still until the enemy has passed them by, in the usual safety of their camouflage, now stand out as unmistakable blobs of white on a dark field.

The coming of permanent cold and thick ice allows the family to shift from its summer ways to those highly special tricks of effectively using a harsh environment that set apart polar people from others of the world.

When the ice has become a foot or two deep in the ground, the man builds a fire near one side of the rectangle that he has marked out to limit his house floor. The small fire thaws down through the newly-frozen ground. When this is completed, the fire is removed and the hole is dug out to a point where a heavy spruce pole can be inserted. Using the pole as a lever, the man with his family bear down, lifting a large block of frozen earth from the area to be excavated. They use the lever again and again, following the outlines of the projected floor, and remove earth economically in large blocks without the need of repeated shoveling with inadequate tools. The blocks are placed near the edge of the excavation to be used later as an outer layer to the house. When a rough excavation has been made, and the walls and corners have been smoothed with hand shovels of caribou shoulder blade, the walls are erected. At the center of the house floor has been left a block of earth a few feet long and about four feet across. This will be removed later. Now four posts are set upright to form a small rectangle near the center of the house. Four more posts are placed at the corners of the excavation, and two at the sides of an entrance tunnel through the front wall. Each of the uprights is notched at the top, or has in it the natural crotch provided by the separation of branches. Into the notches are placed the crossbeams that will support the roof and walls. Four poles extend parallel to one another lengthwise of the house, the two center rafters being the shorter and higher of the four. Poles are placed at right angles to these at the rear and front walls. Now short poles are laid from the ground surface at a steep angle to the lateral beams, forming the walls of the house that stand above the earth walls of the excavation. Other poles are placed parallel to each other at a low angle from the side beams to the central beams, forming the slightly sloping main part of the roof. A frame is left in the roof space between the four center posts, within which to place a removable window. Other poles fill in the remaining space.

Except for a skylight about four feet square, the house is enclosed by earth and pole walls and a pole roof. The family now moves outside and tips the blocks of frozen earth against the walls of the house in such a way as to seal the walls with the moss cover. By placing the blocks against the walls with moss down, earth is prevented from trickling into the dwelling. Other blocks are placed on the roof in a similar way. Soon the entire structure, except for the central part of the roof, has been covered over with essentially a layer of moss and sod above which is earth. Finally, the earth which has been left in the center of the excavation is thrown up through the window to arrange itself over the central roof.

The whole family together throw earth against the house until the structure takes the outward form of a low dome, only the skylight of which is in view together with a low opening at the outer end of a shallow entrance passage. The passage structure is sealed with a light coating of moss and earth, and is covered in front with a caribou skin. The house is now essentially complete. Poles are placed on the earth floor to mark the edges of the beds, and piles of resilient willow twigs are placed within the enclosed areas. Skins are now piled upon the willows and the family has both a bed and a floor upon which to work. In the center of the house an oval or rectangle of stones on edge forms a fireplace. The smokehole is opened, by removing a window of translucent deer gut strips sewn together, and when the fire has been kindled by means of the bow drill, the house quickly becomes a warm and comfortable place in which to rest and live.

When the river ice has become solid from shore to shore, and there is no longer danger that a large crack will form and a block of ice shift its position, the man has decided that it is time to build his fish trap. He takes his ice pick, which is the sharpened tip of caribou antler firmly lashed to the end of a long, spruce pole, and proceeds to chip out holes through the ice at intervals of perhaps four feet. The line of holes runs out to the center of the river or beyond. The outer edge of the line of holes turns rather sharply in a wing pointing upstream. Now the man and a strong helper take up one at a time the small spruce trees with their foliage intact. They push these trees top first through the holes, the branches bending enough to pass through the narrow holes in the ice and then springing out in the water beneath. The trees are rammed hard into the sand of the river bottom. After a short time the surface re-freezes to hold them firmly in place. One after another the trees are inserted in the holes provided until a fence has been formed across a good part of the river. Underneath the ice, the branches of adjoining trees reach out to form a forbidding barrier to fish that come along, but a barrier that does not seriously affect the flow of water. Now, at a deep point along the fence, the man cuts a slot between two or three holes in which he has not forced trees. This long slot is to be kept open for the insertion of his trap. The trap is a large spruce frame, two legs of which come together to be lashed as a common handle. Between the other two legs of the trap is attached a net that billows downstream when dropped into the current of the river.

A peep-hole is now cut through the ice and a shelter erected. In the darkness of the shelter one of the fishermen lies peering down into the lighter water, watching for the whitefish to approach on their journey downstream. At the moment when schools of fish are seen to be diverted by the fence toward the only opening that is left in it, the net is dropped into place, and dozens of fish are at once caught in the folds. Now the man and his family pull up on the spruce handle, lifting the frame, and then slowly drawing out the net with its catch.

The fish are thrown on clear ice near the shore, piled up several inches deep and sprinkled liberally with water at intervals to form a crust of ice over the layer. A pile of fish is thus built up in alternation with ice in such a manner as to preserve the food through the entire season. The icy encrustation offers all the protection that is needed against ravens, wolverenes, and other predators. There is no danger that this cache will be violated as long as ice remains on the river. Armed with his ice pick, a man can secure from the pile at any time a mess of fish as fresh as if it had just come from the water.

The winter house, the ookevik, draws the family indoors for longer periods than does any other type of Kobuk dwelling. During the daylight hours, while the men are away minding their fish traps or trailing animals through the snow, the women build up their fire with driftwood logs, and prepare a meal. A woman draws water in wooden pails from a hole in the river, or she melts new-fallen snow, and fills a large basket or wooden tub with water and meat. Into the container may go fish and caribou meat together, for at this season it is not dangerous to mix one’s diet. A rabbit or so may be combined with a few ptarmigan or grouse.

The fire serves two purposes. It thoroughly heats the walls and floor of the house, through induction providing a base of warmth in the sand that keeps the house comfortable long after the fire has gone out. The fire also heats the cooking rocks. Although a family may now and then roast meat on spits about the indoor fire, most of the cooking is the boiling of meat by means of dropping hot rocks into the containers of meat and water. Stones are gathered with great care. Those that resist cracking when used over and over are cherished by a woman. She handles them with tongs made of two pieces of wood lashed together near one end. She turns the rocks in the fire from time to time, until they have reached a high temperature, when she lifts them cautiously into the fluid of the tub or basket. Several rocks are placed in the fluid at once if the meal is to be a large one, and when the liquid has ceased to boil, they are removed and others relayed. Three changes of rocks are enough to boil the toughest meat to perfection.

Even though the smoke hole is wide and functions with some effectiveness so long as air is regulated through the tunnel entrance and people are not continually entering or leaving the hut, there is often a pall of smoke in the house that causes the occupants to wipe their eyes repeatedly and to lie as near to the floor as possible if they are not engaged in needful activity. A large fire may burn for four or five hours until the house and its floor radiate heat like the firebox of a stove. Then when all of the cooking is done, the woman allows the fire to die down, and with her tongs throws out the brands and embers through the skylight. When the last source of smoke is removed, the window is placed over the roof opening, and oil lamps are lighted for illumination. This is the time of day when children and men return home. The house is now a castle of warmth and comfort. Clothing is removed. The occupants of the hut sit about in abbreviated trunks if they are adult, or in nothing at all. The one meal of the day is ready to serve. First the men gather around the stew pot. They reach in with sharpened pieces of caribou rib, or with spoons made of mountain sheep horn or wood, and secure choice pieces of meat. They blow upon them until they are cool enough to hold in the hand. Then, holding large chunks of meat close to the mouth, grasping a piece in the teeth, and cutting upward with sharp knives, they quickly gulp the meat in large bites with a minimum of chewing. When the man has filled himself with meat, he takes a small basket or circular wooden cup, and fishes out a serving of soup that he then sits back to enjoy. Now it is the turn of the women and children to fish about for morsels of meat until nothing is left but the broth. One eats until hunger is appeased, and then until it is distressing to eat more. When the meal is over those who are seated may fall back and nap among the furs of the bed. The housewife cleans the eating vessels by squeezing from them the excess meat and oil with the wing of a ptarmigan or a bit of old skin clothing. If there is no further eating to do between this meal and that of the next day, it is an individual matter. One searches for dried fish, or shaves the meat from a frozen raw fish which he has brought in from the ice cache.

The woman now sits near to a lamp, her legs outstretched parallel in front of her, and her back straight and unsupported, repairing the skin clothing of her family. She reaches to her belt, grasps the thimble holder suspended from it, and pulls upward the bone cover of her needle case, exposing a number of small-eyed bird-bone needles. She threads one of these with a thin strip of sinew, and proceeds to mend the seams of garment after garment. Clothing must be kept dry, or it will harden, and soft, or it will break the thread, and it must above all be kept mended, or the arctic air will find its way in to freeze one’s exposed flesh.

The children play about on the beds, creeping among the covers, hiding, chasing one after the other, but avoiding as much as possible impinging on the comfort of others. Children are not scolded, although a word of caution is now and then uttered by one of the adults, as though addressed to no one in particular.

Conversation intrigues all of the family. When the current gossip and the recounting of the day’s events have taken place, some one settles down to the telling of a story. Some of the stories are designed to amuse small children, but even these appeal to those of all ages, for the story, whether it purports to tell of something that really happened in the not too distant past, or to explain a mystical event the time and place of which are never made clear, there is no one who is likely to be highly critical or skeptical or completely lacking in interest. This may be the story of the origin of a local mountain. It has been told many times, and always in the same words and with the same gestures, yet it does not grow old. The mountain is a real one that all of the people see continually, and one does not object to being reminded of its presence and meaning to the community.

The family is fortunate to have an old man in its winter house. This grandfather has a great store of stories, and his memory is keen enough now to bring back details of stories that were told to him in his childhood which have since dropped from currency. Grandfather has been working with a piece of mammoth ivory to form the shank of a fish hook with which to catch large shee fish in the early spring. He recalls something that was told him about the mammoths.

“This is Salmon River,” he says, “A man is out hunting. His name is Ataochuk. He is hunting marmots in the mountains. He is walking along on the rocks in his bare feet, for it is that time of year when the marmots are fat and the weather is warm. He has caught and eaten two marmots. After a while the weather becomes bad, and he has to continue along a little mountain trail, even though the clouds are falling low. While he is walking along, he looks far down to the creek, and sees a great big thing walking near the creek without quite touching the ground. He can see its breath. That big thing looks like a dog except that it has fur only on its ears. This man follows that thing. And now, while he is following along on the mountain trail, he sees down there three men behind the animal. They have spears, and they walk also without touching the ground. After a while two of them come right up to Ataochuk while the other man goes on following the animal. And the two men say to Ataochuk, ‘We have caught that big thing that you see for the first time. Come with us and see it.’ Ataochuk says he does not want to go down. They think he is lazy and they offer to pay him to go down anyway. They tell him that if he will come with them, he will become an angatkok (sorcerer) and will be able to see in his own mind where bears are holed up in winter time. Ataochuk does not want to go. He says to those men, ‘If you will give me the power to cut and drill jade with my little finger, then I will go with you!’ And they agree that it will be so with him if he will go. Now they walk down together, and after a while they come to that big thing with ivories that has been killed down by the lake. The ivories grow out of its head. When they get there, the three men work to cut it up, and they take from it a great deal of meat and fat.

“Now the three men tell Ataochuk to get some wood and build a fire so that they can cook some meat to eat. Ataochuk brings a huge pile of dry wood, but when he tries to make it burn, it acts like green wood and will not flame. At this, one of the strangers takes off his clothes and walks down to the lake, and walks under the water to a place where he finds water-soaked wood on the bottom. He brings back this wood from the lake, and when he tries to build a fire, the wood Barnes at once. It looks as if he has put oil on it. Then the three strangers eat a great deal of meat and put more of it in their pack sacks. When they are ready to leave, they say to Ataochuk, ‘Now you may go. When you have walked a little way, you may turn around and look at us.’ Ataochuk starts back home, and after a while he looks back at the three strangers, and he sees them up in the air. They are walking along with packs on their backs up there in the sky.

“Now, when Ataochuk gets home, he takes a piece of jade, and he finds that he can cut it and drill it with his little finger. He is a good angatkok from that time on.”

The old man takes a long time to tell the story, pausing frequently for effect, and acting out with shrugs and grimaces the parts of the characters. When the story is told there follows a discussion of the animals called kilyigvuk. Everyone has seen the large bones and ivory tusks of this animal washing out of the frozen silt banks of the middle Kobuk, and they know that the huge animal burrows underground, but seldom now comes to the surface as it occasionally did in the early days.

The sun no longer has strength. It appears for a short while toward midday, rolling slowly across the rounded mountains to the south, raising itself it begins to change from red to yellow, and then tumbling along the horizon again until it casts only a twilight glow over the earth. Although the daylight hours, toward the shortest days of the year, are long enough to allow a great deal of outdoor work and travel, the actual sunlight is greatly limited, and there are clear days when the low haze on the horizon is enough to obscure the sun. Temperatures never rise above the freezing point. Everything is solidly frozen. The wind seldom blows in this upper river country, and it is possible to stand motionless outdoors more or less encased in an envelope of one’s own body heat. To move is to create a breeze, and to run is to fan the breeze into a freezing blast that can cause exposed ears and nose to become white within a few seconds.

People do not offer themselves needlessly to the cold, of course. Inner fur garments with hair turned to the body are always worn when stepping out of the house, and if an individual is to be out of doors for any length of time, he pulls on his outer trousers and parka and a pair of long boots with soft deerskin soles and heavy sides made from the legs of caribou killed in the autumn. Equipped with caribou skin clothing of this kind, and a wolf and wolverine trimmed parka hood, he is protected against any temperature extremes that the upper Kobuk can offer. If the hands become cold in their loose and heavy wolf-head mittens, a man draws them into his parka and holds them against his body until they are warm. It is folly to allow himself to become chilled, and barring some accident, or the mis- take of over-exertion that causes him to perspire too freely, he does not often become uncomfortable in the winter of extreme cold.

This is the “shortest ice moon,” that corresponds most closely with December. The next moon is called “the sun returns,” and it is during this period of time that the families camped along the upper Kobuk are invited to get together for the festivities at a locality far down the stream.

A trading feast, or still another form of ceremonial takes place somewhere within travelling distance nearly every year. An invitation has already been received this year from the Squirrel River people. The groups of families that customarily hunt and fish along the Squirrel River and neighboring banks of the Kobuk nearest to this tributary have decided to build a kazgi, or ceremonial house, and arrange their fall fishing camps in the near vicinity of this kazgi in order to be hosts to people from surrounding regions.

Earlier in the season, while our family in the upper Kobuk had been just completing their winter house they had received a call from two young men who acted as kevghut, or messengers. These were two of the strongest and fastest runners among the young men of the Squirrel River people. They had been bidden

by their group to invite chosen families from the upper river and other places, to come to their festivities.

Each had been given a “reminding stick” about four feet long and an inch thick. The stick had painted on it, in graphite, red ocher, and other pigments, series of rings and dots, interspersed with strips of skin. One strip of skin stands for each family to be invited Kevghut remember who they are to invite by the strip of skin that represents those persons, and they remember into the sticks, so to speak, what the invited persons have said. Kevghut travel together, but say little to the people they invite. Their minds must be clear for the information that they are to carry back. When these particular kevghut had arrived, they had been wearing only short boots, short trousers, and little jackets with sleeves above the elbows. Their arms and legs had been painted with designs in charcoal. Each had carried only his inviting stick and his bow and quiver of arrows. They had run all the way and they were expected to continue running when not actually giving invitations until they had delivered all of the messages and returned. The kevghut, standing formally at attention before the upper Kobuk family had repeated the message that they had been asked to impart from the “partner” of the man with whom they were talking. This man has a partner-a sort of blood brother, among the Squirrel River people. The distant man had sent word to his partner to make requests for presents, so that they could be prepared for him when he reaches the rendezvous. This man had consulted with his family, and they had decided upon the presents they would request. Perhaps it had been for big seal-skin from the sea coast with which to make boot soles, trade metal, or beads, or perhaps the graphite to be used as paint that comes from the mountains of Squirrel River. These and other items had been enumerated in order, and the kevghut, looking intently at the designs on their inviting sticks, had memorized the requests that were made. Then the two young men had started running again to the place where they would find the next person to be invited.

And so it is a topic of recurrent conversation with this household that they will soon be leaving for the trading feast. The day on which they are to arrive at Squirrel River is determined by a phase of the moon, and everyone watches with great interest the transitions in the mid-winter sky.

Things do not go along smoothly before the trip down river, however. One day a boy arrives from a neighboring house, a few bends of the river away. He explains that the old man of their household is very ill, and that they will need help. The father of this family quickly harnesses his dogs, asks his wife to look after his special snares, and drives away with the boy towards his neighbor’s hut. When the two arrive at the house of sickness, they hear the beating of a drum, and now and then a bit of chanting that is not entirely muffled by the earth and snow walls of the underground house.

When the visitor has bent over and crept through the entrance passage, and has thrown aside the skin inner door, he sees lying upon the willow bed a naked and emaciated old man. Bending over him is a wrinkled woman whose hair is mixed with gray. Seated cross-legged nearby is the old man’s son, in whose hands the tambourine drum is resounding rhythmically to sharp claps across its rim made by a long and flexible drumstick.

The shaman, Mituk, is doing his best for the ailing man. He is standing, grotesquely illuminated in the light of a single oil lamp, ready with his drum for another incantation. Mituk’s face is streaked from the eyes outward with broad, black marks, and from a lock of hair over his forehead hangs the white skull of a mouse. He is naked except for abbreviated trunks, and charcoal stripes decorate a large part of his body. The visitor says nothing, but shakes the snow off his parka, and then removes his other clothing to take his place with members of the household on the bed space opposite that of the sick man. He watches intently, and listens to the words of Mituk, who is now ready to begin another seance.

A number of people who are not closely related to the old man sit about the large room. Mituk begins to work with his own spirit drum, the handle of which is decorated with the grotesque head of some animal-like figure. He drums slowly, chanting to the even, continuous beat. His patient appears to be either asleep or unconscious. His breathing is heavy. After a long and monotonous period of drumming, Mituk throws out his arms wildly and in a falsetto, complaining voice, announces that he must be tied up in order to make contact with helping spirits. Two of the men obtain rawhide line, and do as the old shaman bids. He asks them to bind his ankles closely together, then his wrists behind his back, then his knees, and now to draw the line between ankles and wrists as hard as they can, until there is no possibility that he can free himself. This is done, with a show of strength on the part of the helpers. The shaman winces with pain. Soon he is trussed so tightly that his breathing and the moving of his neck is his only display of freedom. Now, at his bidding, the men place over him his drum and drumstick. Mituk asks the other drummer to continue his rhythm without fail.

Slowly the drumbeats become the only sound in the hut beside that of the heavy breathing of the patient and of Mituk himself. Mituk begins to talk, this time in a high voice unlike his own. He asks that the lamp be placed in the entrance hall, so that no light shows in the room. When this is done, and the eyes of those present can make out only the shadows of things, Mituk begins to talk faster, until his sounds become a chant to the rhythm of the drum. Some of the words are unclear, but his listeners hear him say that now he is beginning to leave his body, and they hear the sound of the high-pitched voice moving about the room. There is the flapping sound of great wings against the walls of the house. A child shrieks, but all else is still as everyone concentrates on the sounds of the angatkok.

If this is really Mituk, his voice bas become almost unintelligible. It sounds more like that of an eagle. At length the voice seems to fly out through the roof of the house, and becomes fainter and fainter in the distance. The drum beat continues. Every so often one hears in the distance a shriek or a wail of some unearthly sort, and it is known that Mituk is flying away to make contact with his spirit helpers, and to learn what it is that is causing the illness of the old man. At last the distant voice becomes more intelligible. It seems to be approaching. All at once, it surges into the house again. The flapping of wings dies down and the high voice becomes slowly that of Mituk-centered again at that place on the floor where he has been tied for the seance. He now asks, in a tired voice, to have the light brought in.

By the light of the lamp, everyone sees that Mituk is still tied just as he was in the beginning. The knots seem to be precisely the same, but the shaman is perspiring from every pore, and he breathes as though exhausted from a long journey. At his bidding, they untie the knots and release him. He works his wrists and ankles to regain circulation. At length he tells them about his spirit helper – a grotesque creature unlike any that other people have seen – and what this spirit has told him about the ailing patient. It seems that the sick one has inadvertently cut the flesh of a bear which he and others had killed in the fall with a knife that he had previously used in the skinning of a wolf. The spirit of the bear had been strongly offended, and had taken action against the offender. Now Mituk approaches the body of the old man, and begins to work with his hands at a point below the right ribs. At last he bends over and sucks hard at the offending place, and with a loud noise seems to extract something from the body of the sick man. He rises up and spits into his hand, in a spray of blood, the flint point of an arrow such as people had used in earlier times. o mark is to be seen on the body of the patient, however. The extraction has been miraculous.

The seance is over. The group can only wait to find whether or not the activities of the shaman have been in time to prevent the death of his patient.