April is the Persian month. The plane wings over the high mountains ringing the plateau and finds them mostly free from snow with soft green spilling over the foothill valleys. In Teheran the ubiquitous rose graces every garden pool and is carried by every passerby, adorning even the gun barrels of soldiers on watch. The rains are over, and the sky clear for a short while until the summer winds bring the dust. A perfect time to begin an expedition.

The Expedition, one lonely assistant curator at this point, began with the usual two-week round of calls (tea and pepsi cola), letter writing, and planning. The aim of the operation was to review the northern regions with an eye to future operations as well as to obtain additional information for use in writing up material already in the Museum’s collection in Philadelphia. This process was greatly facilitated by the cooperation of Mr. Samimi, acting director of the Archaeological Service, Dr. John Elder of the American Presbyterian Mission, and Col. “Pete” Smith of the Military Mission of the United States in Iran. The Colonel was an enthusiastic amateur archaeologist and generously made several side trips from Teheran possible during the period of delay.

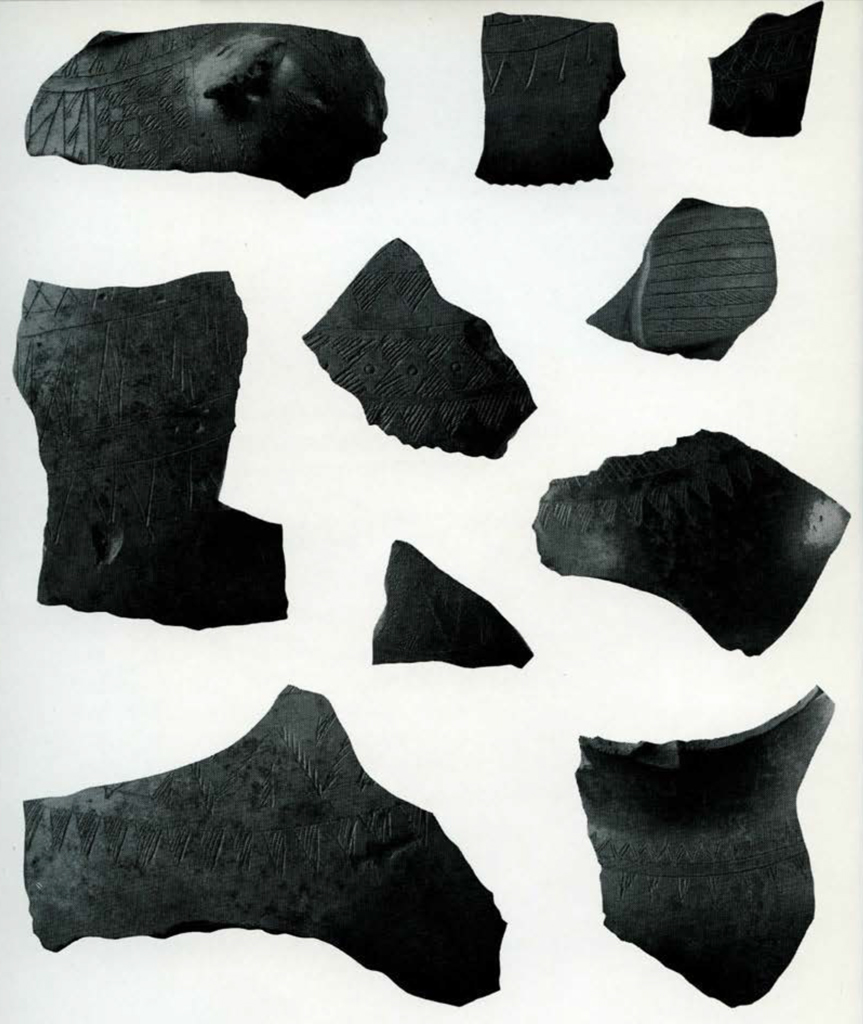

Image Number: 62246

One of these trips began in the Colonel’s tool shed which housed a large collection of unbroken pottery excavated from a small site forty miles west of the city. It has been said of many areas in Iran that the lack of visible mounds indicates a lack of habitation in ancient times. Such regions have, therefore, been written off archaeologically in favor of the more obviously occupied areas. This is particularly true of the foothill valleys along the Elburz mountains which separate the plateau from the Caspian Sea. The visit to the Colonel’s site near the village of Chandar, showed a small cemetery area enclosed by the remains of an oval stone wall, and not far away a village area on the edge of a deeply eroding stream channel. The remains could be detected only through the presence of scattered potsherds and boulders which on closer inspection formed rows marking the lines of walls.

The pottery on the surface was the same in both areas. The major ware was the fine grey ware with a high burnish like that found at the site of Tepe Hissar by an earlier Museum Expedition. In this case, however, the shapes represented belonged to the period which followed the final occupation of Hissar: tripod bowls, cups with single loop handles, jugs with two or sometimes three handles, and jugs with tubular spouts or open spouts on the rim. Also included were a coarse brown ware, a few pieces of a red burnished ware, and rare examples of a red-slipped ware with black geometric designs painted in a sloppy manner.

Museum Object Numbers: 53-31-2A / 53-31-2B

Various copper or bronze objects had also been found by the treasure-hunting villagers in the cemetery. These included torque-like armlets, simple bracelets, pins with grooved stems, flat arrowheads with tangs (in some cases squared off), and bronze daggers with compartmented handles which originally held inlay of some kind. All of these features and the pottery indicate that the material falls somewhere in the middle second millennium B.C. in date and thus helps to fill a gap in the known sequence of Iranian cultures. The Colonel very generously pledged a selection of the material to the Museum for its collection.

Another interesting side trip took us south to Kashan, site of Tepe Sialk, the oldest continuously occupied site known on the plateau. The trip took three hot days due to the roads-the final sixty miles taking four hours to cross! On the way down we spent the night at the hotel in Qum, one of Iran’s holy cities and noted for its religious conservatism. The mosque, whose golden dome dominates the skyline in the day time, is sacred to the women of the country. At night it is brightly lighted by fluorescent tube lights ringing the four minarets. The hotel is only a block away, and the rare foreign women visitors find it politic to dine in their rooms rather than risk an incident by appearing in public without a black chaddar or shawl.

Museum Object Numbers: 53-31-5 / 53-31-4 / 53-31-3

The site of Tepe Sialk occupies two mounds near a fine stream which pours from the mountains and disappears in the desert. The earliest occupation levels dating back to the fourth or even fifth millennium B.C. are now some 6 meters below the present level of the plain-mute witness to the enormous changes wrought in the landscape by erosion. Small wonder that early sites are hard to find! After making our study of the site and gathering sample pottery for our study collection, we found that a place to stay was equally hard to find. Kashan is to say the least “off the beaten track,” the only “hotel” being a black and smoky chamber over the Bazaar. Preferring the danger of exposure to fresh air we finally prevailed upon the gate keeper of the famous Kajar palace at the edge of town to let us sleep there in one of the many pavilions. The gardens are unique with many pools and fountains fed by a mountain stream in much the same manner as the famous ones at Tivoli outside Rome.

After a few more days scrambling about Teheran, the expedition, now joined by Mr. Taghi Assefi, Inspector of the Archaeological Service, set off one bright morning to the east and the site of Tepe Hissar, excavated by Dr. Erich Schmidt in 1931-32 for the University Museum. At five p.m. (after ten hours of driving during which we traveled as far up and down as forward) we arrived in the town of Damghan and were received by the local medical officer, Dr. Hushmand. After several glasses of tea, a plate of pistachio nuts, cookies, and a halting three-way conversation in English, French, and Persian, the long battle with steering gear caught up with the author and he was put to bed-to be re-awakened at ten p.m. for a delicious dinner consisting of a huge fresh vegetable salad, a high mound of pilau, green plums in honey, and tea.

Image Number: 62247

The following day after minor car troubles we drove to Tepe Hissar fording several newly eroding channels in four-wheel drive. As at Sialk the early levels of the site lie below present plain level. Again the broken pottery was of interest in relation to many puzzling questions about cultural movements. The same painted designs and ware have been found at Kashan (Tepe Sialk), near Teheran (Chashmi Ali), at Tepe Hissar and farther east at Nishapur. Pottery of the same type was recovered at Hotu Cave by Dr. Coon’s expedition several years ago. In studying the Hotu material we had been handicapped by a lack of comparative material from these sites as well as certain gaps in the published reports. These blanks were now being filled in, and a study collection unique in the United States being built up. One of the puzzling aspects of Hissar was the lack of any reference in the published accounts to a coarse plain ware for every day use. This was of interest because of the abundance of a coarse straw-tempered ware at both Sialk and Chashmi Ali. At the site of Hissar, however, in spite of great mounds of broken painted pottery on the dump there was no plain ware to be seen from the early period. After much searching, the face of one of the deep pits finally yielded from the lowest horizon several painted sherds, a blob of copper slag, and one plain ware sherd-a brown grit-tempered ware related to the coarse ware of the later Grey Ware periods and quite unlike the plain wares of Sialk associated with the early periods. Why there should be a virtual absence of coarse domestic pottery here, and what the significance of a different type of coarse ware in the earliest period may be are questions to be answered in the future.

From Damghan we drove a little farther east and then dropped down from the 1,850-meter plateau to the Caspian shore for a visit to Tureng Tepe, a large mound briefly investigated for the University Museum by Frederick Wulsin in 1931, and presumed find-spot of the famous Asterabad Treasure. On the trip to the site the expedition was accompanied by an official of the Education Ministry in Gurgan, a local Turcoman guide, and a slow steady rain. After a semi-sideways drive across numerous meadows and ditches we finally gurgled to a stop half buried in grey mud where a broken irrigation ditch had washed out part of the road. A large part of the morning was then spent extricating ourselves. The mud was so slick it was almost impossible to remain standing on it, and indeed two towering Turcoman horsemen, watching us with much amusement trying to climb to the mound, suddenly found themselves and their horses sprawling on the ground.

Museum Object Number: 53-31-6

The site itself forms a sort of rectangle with an oblong pond in the center. On one corner of this mound area there is a low oval platform occupied in part by a tall conical mound very reminiscent of the ziggurat mound at Nimrud in northern Iraq. At one point in its history this tall mound was scorched by a great fire as shown by the red oxidized sides and a burned surface about a third of the way below the top. After the fire the mound was reused with further construction in grey mud brick. Halfway up the side facing the pond, and elsewhere on the platform boulder wall foundations were visible. Tests made by Wulsin indicated that this entire structure was of solid mud-brick. It obviously has had a long and complex history. Orange burnished pottery of the type known from other sites in the area and at Hotu Cave occurred on the upper slopes, while lower down and on other areas of the mound the burnished grey ware appeared. A very interesting site indeed but unfortunately close to the Soviet frontier.

After brief visits to Belt and Hotu Caves to clarify certain points about the cultural sequence at these sites, we returned to Teheran to meet Mr. Jason Paige, Research Associate of the Babylonian Section, and to have our Land Rover overhauled before setting out again.

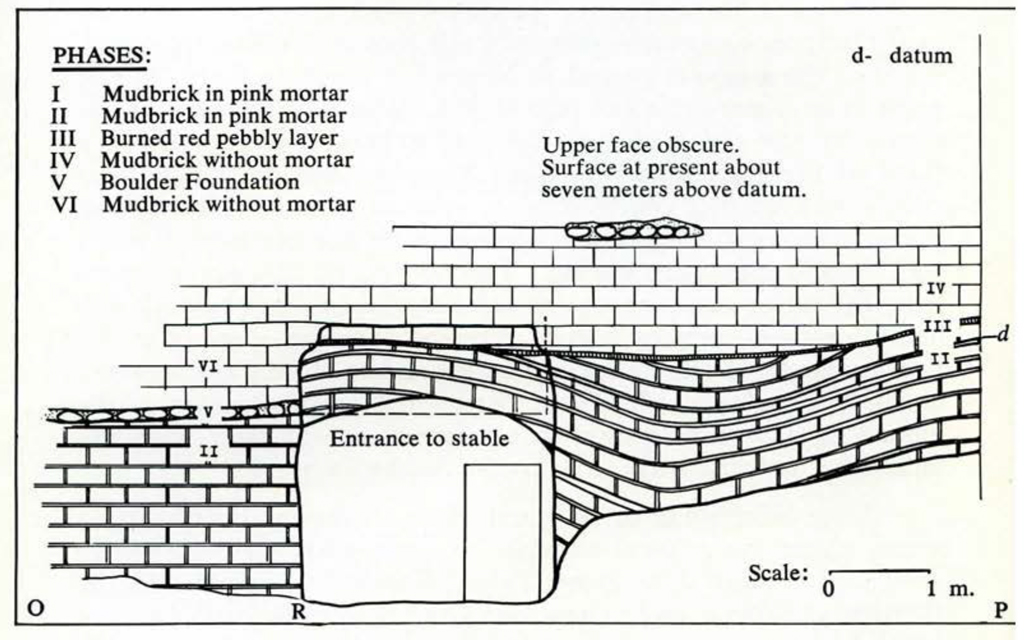

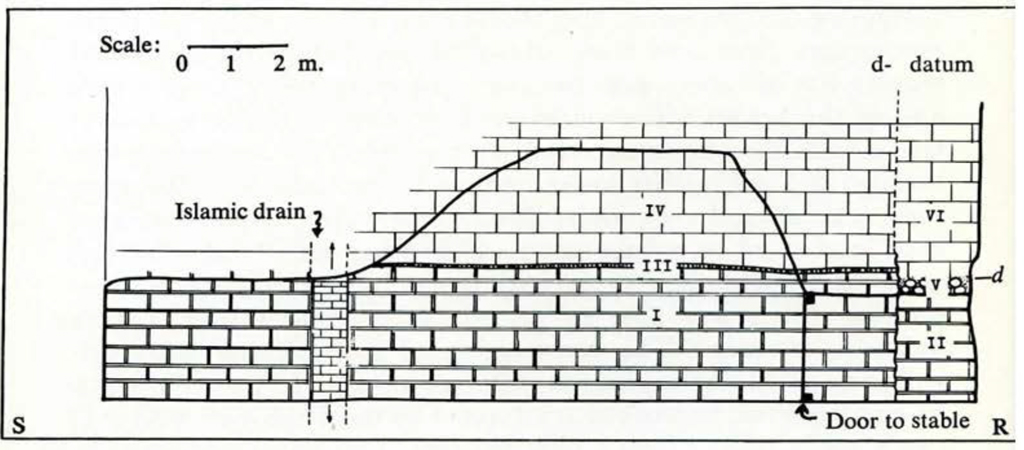

Our next major study was made at Hamadan where we spent a week mapping and drawing sections along Ecbatana Street, a new road which cuts through twenty feet of the ancient mound containing the remains of the Median and Persian citadel. Formal excavations have not been allowed here, but much clandestine digging has of course gone on, and many quite deep holes are open among the houses. The outer brick defense wall can be readily traced with the aid of an aerial photograph. The new street cuts through this wall at its lower end, and into bedrock at its upper end. The natural rock slope down to the plain appears to have been leveled off as a base upon which other walls and structures were built. Although prohibited from doing any digging here, the expedition was able to record some sections with a little judicious scraping. The construction of stores along this route will soon hide these exposures. The section showed an initial phase of building upon bedrock characterized by mudbrick (35 x 32 x 13 ems.) set in thick (5 cm.) pink mortar. This phase was standing to a height of 2.5 meters, and from the zigzagging outer face of the fortification wall inward for a depth of 13.70 meters, as shown in a stable hollowed out of the solid brick. The exterior facing of this wall had been rebuilt at least once. The surface of this phase was then covered by a burned level filled with small pebbles. Above this the walls were rebuilt without mortar as a rule of grey mud- brick (37 x 37 x 15 ems.). In a number of places there appears to be an interval of erosion between the two constructions. The second phase remains standing in places to a height of 3 meters. Elsewhere it also shows traces of erosion and in one area two fragments of broken stone column bases have been pushed into holes in this surface. At some subsequent date the entire area was then leveled off and new streets of cobble stones and houses built. Between this level and present surface lie two to four meters of additional debris. A few rare blocks of cut stone are to be seen in neighboring houses, but no floor levels associated with the two early phases of brick-work could be established in the sections, nor at any other points observed on the site.

Museum Object Number: 56-20-1

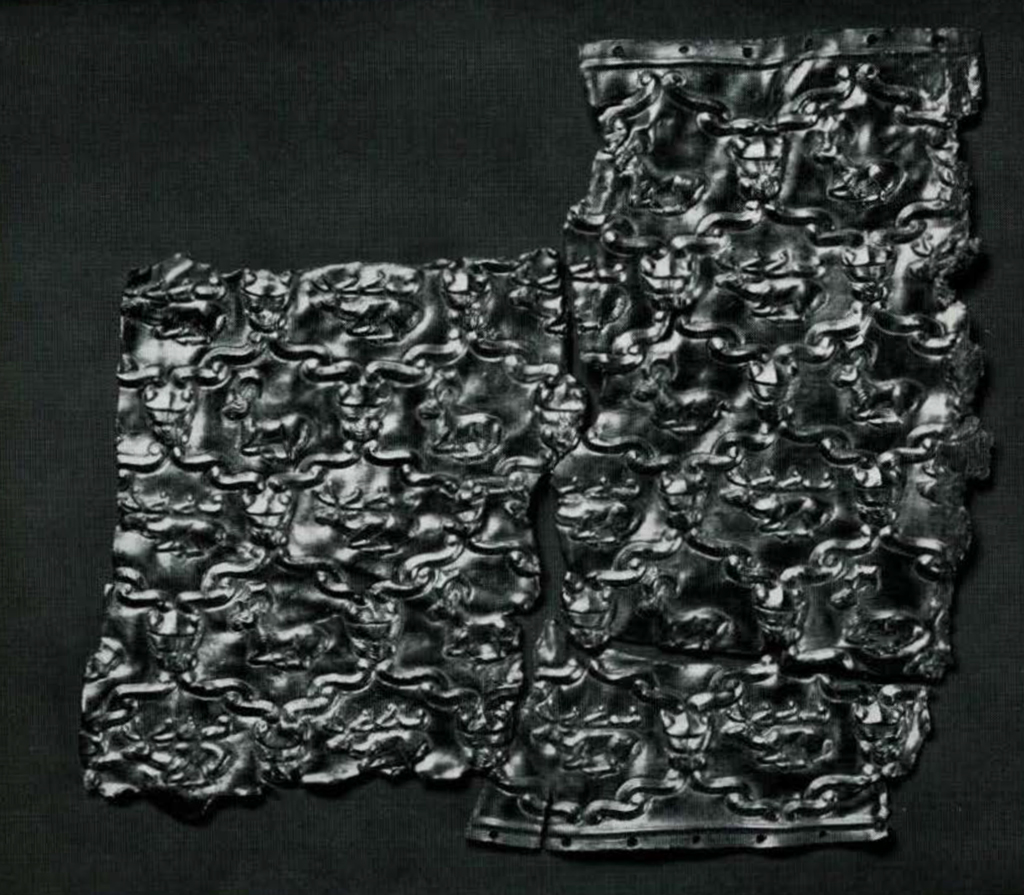

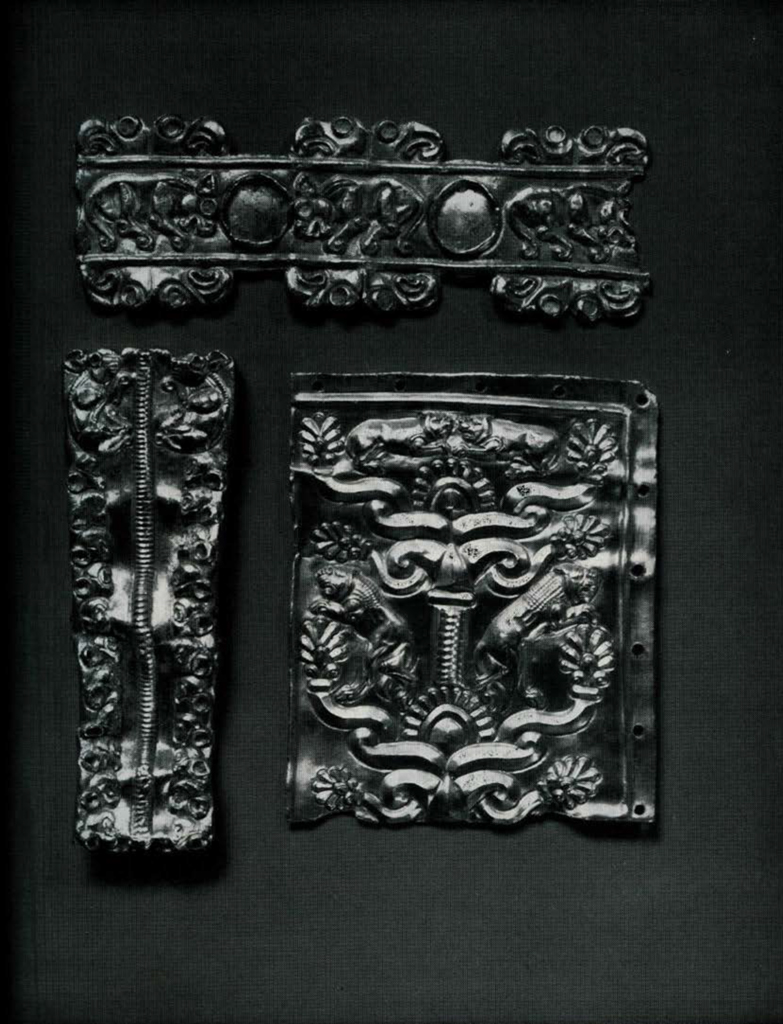

From Hamadan we worked our way westward to Kerman-shah. From there we drove north over a difficult road to the high plateau (over 2000 meters) of Kurdistan. Here we visited the remote site of Ziwiye, reached by a three-hour cross-country drive. The fortress site rests on the top of a hill which rises some 250 meters from the valley floor. Since the original discovery of a cache of gold objects here in 1947, excavations have been continued each season without further results. Since the date of this cache is in dispute and several pieces are now in the Museum’s collection this problem attracted our attention. The square cuts into the mound on all sides reveal various floors and walls of mudbrick. In one area several stone column bases suggested a portico of some kind, while in another a number of triangular glazed tiles suggested some elaborately decorated structure. There was no visible evidence to suggest destructions and re-occupations of the site. The pottery dumped from various soundings was consistent in type (except for the very top of the mound where only heavy storage jar fragments occurred). It consisted of a fine buff ware slipped dark red, mostly in a shallow dish form, Late Assyrian pottery at Nimrud; a buff ware with smooth greenish to greyish white slip in the form of round jars with high collars, and in one case a tubular spout. Most abundant was a very fine buff ware with a very smoothly burnished surface in various bowl forms and collared jars; and a coarse domestic ware with simple rims and horizontal lugs. One fired brick measured 34 x 34 x 9 ems. while bricks exposed in the walls measured 37 x ? x 12 ems. and were set in thick mortar recalling that at Hamadan.

Also evident were small fragments of copper with repousse animals, copper rivets, and three-flanged arrowheads. These are important in dating since they become particularly common in the Achaemenian Persian period, and are unreported anywhere in stratified context in the Near East prior to the eighth century B.C. The publication of some of this unspectacular material should be of great help in settling this question.

The final important stop was made at the site of Hasanlu just south of Lake Urmia. H ere we spent ten days making soundings with specific aims which were largely accomplished. The site had been briefly explored by Sir Aurel Stein in the thirties, and the Iranian Archaeological Museum had excavated a number of graves. The present expedition made a sounding (Al) in the center of the central mound to obtain concrete data on the amount of late material present, the stratigraphy of the upper levels, and the presence or absence of architectural features. The results showed a meter of deposit containing two flagstone stairways of uncertain but probable pre-Islamic date, two meters of burnished grey-black and red wares (of Iron Age type) associated with a massive boulder wall, and below this the top of a stratum containing light buff ware with brown painted geometric designs of the Bronze Age.

A second sounding (C9) at the outer edge of the central mound, cut in horizontally just above Stein’s superficial trench, encountered no fortification walls, but instead revealed tip lines in the debris indicating the presence of higher surfaces to the right

Article Incomplete

1 Photographs are by Reuben Goldberg. ↪