It was April when I arrived on Melville Island, in the company of a small group of men, with the purpose of studying the culture of the Islanders, and it was eight months later that 1 packed up my notebooks and flew home. During this time we were amply supported by the National Geographic Society and the University Museum.

In my notebooks was all the information I could gather concerning the way of life, past and present, of this particular tribe of Australian Aboriginals. Much of the information in these diaries will eventually find its way into proper chapters of a Ph.D. thesis concerned with the particular economic system, tribal organization, ceremonial activities, and so on. My hand-written notes of day-by-day observations will be transformed through analysis into scientifically derived generalizations so that the information will be in the form most useful to other ethnographers. Included will be the so-called “typical daily life” of a group of interesting and very primitive hunters and gatherers; but because of the demands of time and space some things will be left out: the account of a succession of days, some of which were perhaps almost “typical,” but most of which were unique, made so by the personalities of the particular people I was with, by the weather, and by hundreds of little incidents. Only by mixing the days together can one describe a “typical” day and then it becomes a classification and not a true description.

I think something very real is lost by the scientific demands of ethnological reports, so I would like to take this opportunity and space to record some of the incidents which occurred during a series of seven days when I accompanied a group of Melville Islanders on a hunt. The trip took us to a small clearing on the right bank of the Paluwiunga River, ten miles upstream from where it empties into the Arafura Sea.

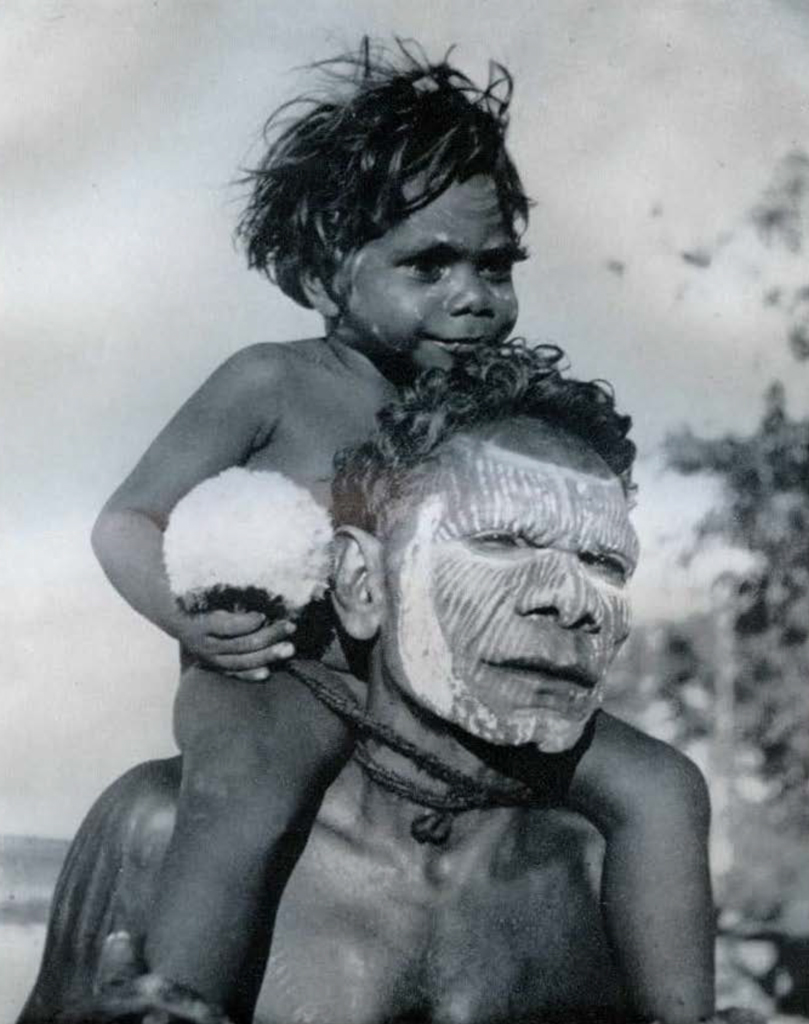

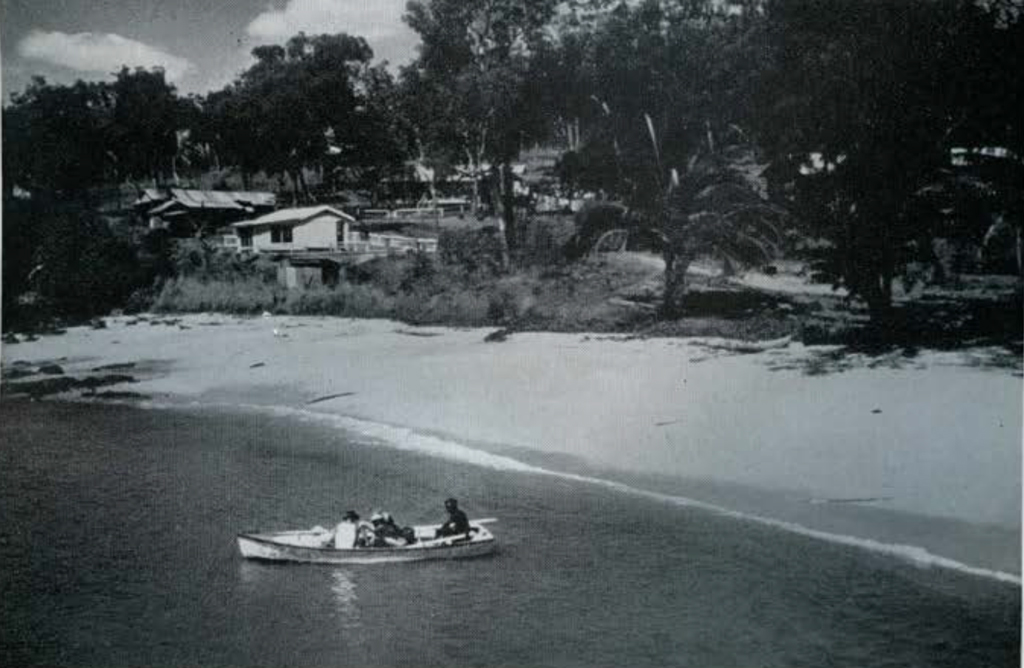

A brief glance at the map will help to further pinpoint this location. Ten degrees south of the equator and at a distance of twenty to fifty miles due north from the Australian Northern Territory capital of Darwin, lies the relatively large Melville Island (1,000 square miles), named for Viscount Henry Dundas Melville, First Lord of the Admiralty, who authorized the coastal survey of 1818 during which the island was circumnavigated. To the west, separated by a narrow strait, lies the smaller Bathurst Island. The group of people with whom I found myself camped by the river bank were members of the Tiwi, a tribe of Australian Aboriginals whose country includes both these islands. Today about seven hundred members of the tribe live near to the southeast corner of Bathurst Island where they are in various ways administered to by the Sacred Heart Mission. On the northern coast of Melville Island, on a hill overlooking Snake Bay, near the mouth of the Tjipripu River, stands the Snake Bay Native Settlement where about 180-200 natives live along with two or three white employees of the Department of Welfare of the Australian Government and their families.

Image Number: 67904

It was not always like this. Formerly there were no white men and the tribe lived scattered throughout the entire countryside. The land was divided into “countries,” each owned by a division of the tribe, and providing the owners with all necessary food, clothing, and shelter. Although many changes have come to the tribe in the last fifty years through contact with the early buffalo shooters, the missionaries, and the government, the individual Tiwi is, with few exceptions, a hunter at heart. He may have acquired new skills such as a knowledge of English, and the ability to work at cutting lumber in the sawmill or driving a truck, but in doing so he has not lost the skill to track down the wallabies or possums in the bush or fish in the sea, nor has he lost the desire to do so. There are, of course, exceptions-those who prefer working in the settlement or in Darwin and attempt to make their own way into the white man’s world. A few are successful and never return; others, not so successful, try it for a while and return to alternate between doing their bit in the settlement and going on “vacation” into the bush when they feel the need of a change of pace.

By the end of October I too felt the need of a change of scene. I had been living at the settlement or close to it for seven months. I had watched the Tiwi as they built-the settlement buildings, started formal schooling and helped run the everyday affairs of a community of two hundred souls. I had watched them in the evenings when they often performed portions of their lengthy ceremonies necessary to the proper burial of a fellow tribal member. I had accompanied them on weekends whenever they had camped in the surrounding countryside, and had gathered and consumed the tasty native food as a variation to corned beef, vegetables, Hour, tea, and sugar of the settlement menu. But after seven months I too grew tired of corned beef, and as the daily increasing humidity announced the approach of the wet season I was anxious to go hunting once more before travel became difficult. Another sign of the approach- ing change of seasons, observed with great interest by the natives, was the increasing flocks of geese Hying over to the cast of us to their feeding grounds in the fresh- water swamps at the head of the Paluwiunga River. Since the Superintendent of the settlement had a plan to build a permanent camp for future crocodile hunts near this very spot, this seemed an ideal time for all concerned to make a trip to this area.

Image Number: 67905

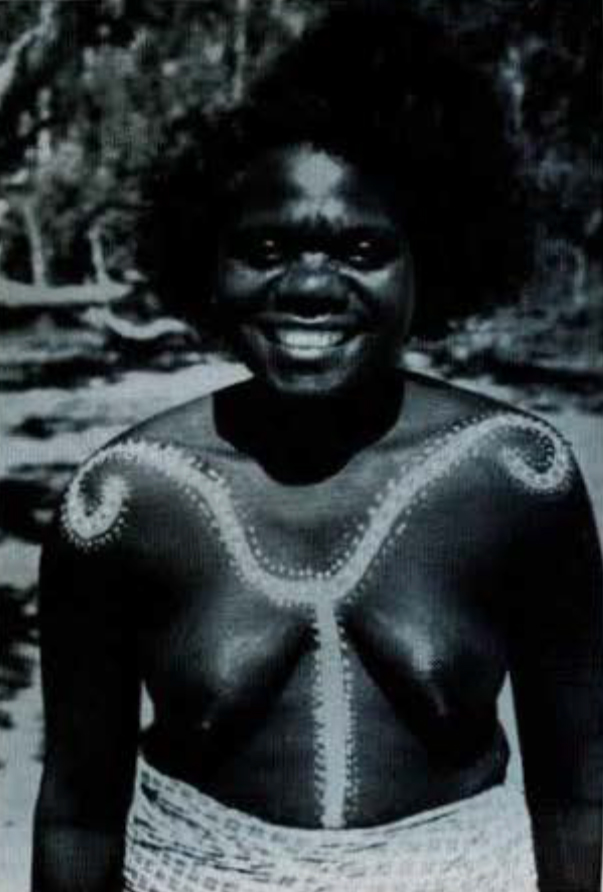

As there was a shortage of water transport (only four dugout canoes and one small motor launch), the main group of twenty men, women, and children was taken in the canoes across Snake Bay the day before and left to ” foot-walk” along the coast to the Paluwiunga. The Superintendent and his son went ahead in the motor launch and I followed the next day in “number one” canoe with my chosen companions. I had originally invited my chief informant Dolly and her husband Malony, but they had had a “proper row” a few nights previously and weren’t speaking. Dolly would have come alone because the object of this row, her boy-friend, Billy-Two, was going, but public opinion was too strong in view of the very recent objection by her husband, and she begged out of the trip. ln their place the choice of Albert and Agnes was obvious. They had been close associates of the expedition and of mine since our arrival. They were a young couple in their early twenties, but recently married, and very much in love-there would be no complicating boy-friend problems with them. But above all, Albert loved to hunt and he was a good man to be with in the bush. He was a quiet, serious young man and very modest about his accomplishments. Because of this he was not a good informant for native lore or customs; he would always refer us to the old men who knew much more than he. However, he was a conformist to these lores and customs, and if the white people were disappointed by his performance in settlement work, the old men of the tribe were just as pleased by his attitude to his native heritage.

Agnes, a slim tall girl of twenty, was even shyer than Albert and to cover up this shyness she always smiled or giggled. She was a cheerful soul to have around. Feeling that the responsibility of the care and feeding of the murandanga (female white person) was a little more than their young shoulders could bear, Albert asked Big Jack, his older brother, a “big man” in the tribe to come along. At the last minute a fifth member was added, Tchuwiunga, a tiny black-and-white puppy of about eight weeks old.

Number one canoe was the largest canoe and was considered the safest. The Malay fishermen, a century or more ago, had taught the Melville Islanders how to hew a rough canoe from a single log, but the art had never been perfected. This canoe measured about fifteen feet in length by about three feet in width at the center. There were small platforms in the bow and stern which served as seats except when the mast was mounted in the forward platform.

Image Number: 67906

It took us quite a while to load, but we finally launched out into the bay about mid-morning. In the stern, sat Albert, his knees folded under so that as he lifted and dipped the heavy ironwood paddle only his arms and back supplied the power. He kept in perfect time with Big Jack who sat just in front of him. They would both paddle on the same side for about six strokes and then bringing the paddles overhead would continue on the other side with perfect rhythm. Agnes and Tchuwiunga sat amidships among the rolls of blankets and cartons of food, while I surveyed the scene from the forward seat, clutching my waterproofed KLM overnight bag containing my camera, toothbrush, and change of clothing and the ever-present supply of pencils and “six-penny” notebooks.

The bay was smooth, too smooth, for not a ripple broke the gently rolling surface. We could, however, see and hear breakers on Piriu Point; so, with the promise of some wind to propel the craft, and incidentally break the close, muggy atmosphere, Albert and Big Jack paddled strongly and swiftly so that soon we reached the opposite shore and began to work our way up to the point. Although the men were silent, Agnes entertained us with the singing of other women’s love songs. All women, regardless of the degree of affection they have for their husband, have lovers and compose long love songs extolling the chosen man’s virtues. Agnes, however, only sang her song about her lover, Ginger-Two, when out of audible range of her husband.

Image Number: 67907

About noon the canoe rounded the point and at once a strong easterly wind prompted us to raise the sail. This required little effort as the thin and greatly patched canvas was permanently attached to the 12-foot mast and boom with wire. All that was needed was to drop the mast through a hole in the forward platform and let the boom fall into place. Unfortunately it was soon apparent that the forces of nature and the design of the canoe were against us; the wind was too strong and without a keel the canoe could not head into the wind which was dead against us. The mast was unstepped, the sail furled, and the paddles taken up once more, but now instead of a calm sea we faced large rollers, some of which broke under the force of the wind. It was heavy going; Agnes clutched Tchuwiunga more tightly and l hugged my KLM bag while the two men worked to head the canoe into the largest waves while trying at the same time to head in towards the shore. This meant taking a good many not so large waves broadside and we got very wet. Facing sternwards, I could not see the waves, so if a particularly large one (Agnes called them “female waves !”) approached, l would be given a few seconds warning and would duck the breaking spray which would cover the boat and its occupants. The only miserable one was the puppy who presented a very puzzled and hurt expression as he peered out from under the folds of Agnes’s naga. For the rest of us the cold spray was a welcome relief from the burning sun.

Once in close to the shore, our skilful paddlers brought the canoe safely onto the beach, riding in on one of the breakers. We unloaded everything, although we intended to stop only for lunch, for the canoe would soon be swamped by the sea if left alone. After unloading, Albert swam the canoe out beyond the breakers where he anchored it with a large rock.

Then we climbed the low dunes close to the shore and came to a grove of casuarinas. These provided much appreciated shade but a very uncomfortable carpet of spiny seed pods. Taking up our two billy cans, Agnes led me to the back of the grove where she showed me a small well. There were many footprints around the sandy hole which were identified as belonging to Black Joe’s mob, the natives who had preceded us. They had, however, not depicted the well for in the bottom was a small puddle, and since this was at the very end of the six months dry season, it was considered fortunate that there was any water at all. Agnes carefully tasted the water and declared, “it was o. k. for murandanga,” meaning that it was not too stagnant or brackish for my health. By digging up some of the wet sand from the bottom of the well, the water seeped in to fill the void and soon we had our two containers filled. By this time Albert had started the fire and unpacked our canned rations.

Image Number: 67908

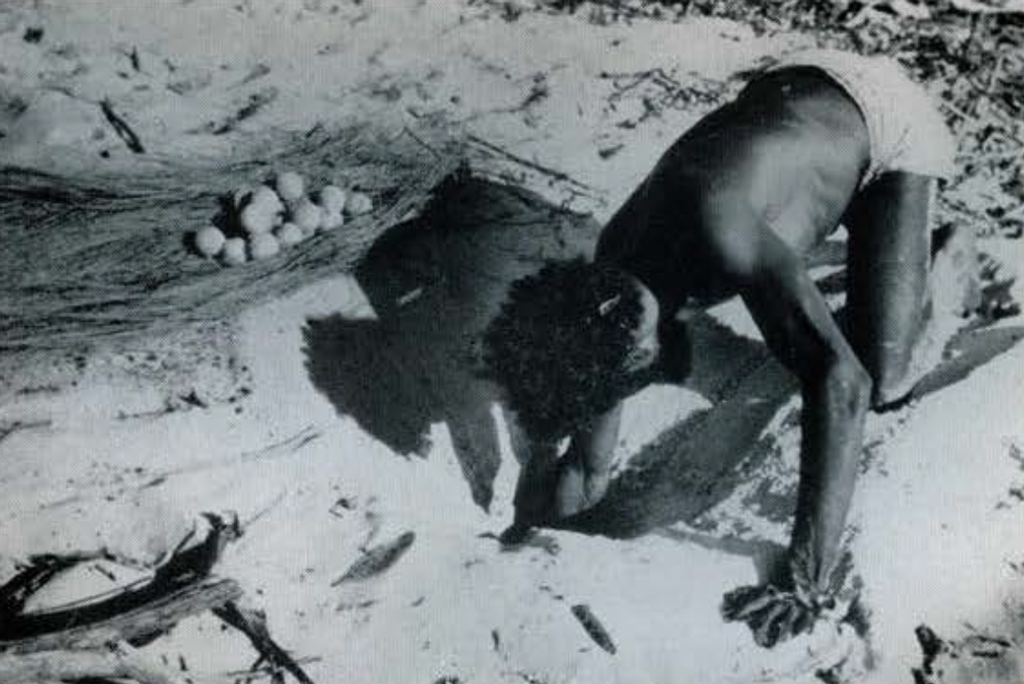

One billy was placed on the fire for “tea leaf” and we broke open some corned beef and a loaf of fresh bread thoughtfully provided by the Superintendent’s wife. When the billy boiled, a handful of tea and two handfuls of sugar were added and the pot set aside to cool. Big Jack bad in the meantime gone over the dunes to look at the sea, and he reported that the wind was still too strong to allow us to continue in comfort and safety. We might as well take it easy for an hour or two and wait for it to calm down, he said. Almost immediately Albert and Agnes were fast asleep, their heads resting on tins of beef. Big Jack, however, took the axe and wandered off into the bush in back of the camp. After an hour it was obvious that the wind had no intention of dying, so we roused ourselves and strolled off down the beach in search of turtle eggs. We saw many tracks of the female turtles where they had lumbered out of the water up to high-water mark, and the mounds of sand kicked up while they dug their deep nests. Using a long, slender stick, Albert probed around these mounds hoping to feel the soft resistance of the rubbery eggs. Time and again he probed in a different nest quite unsuccessfully. Criscrossing one of the tracks leading to a nest were many little ones returning to the water; these eggs had lived to hatch. Finally Albert gave up, remarking, “That Black Joe mob make plenty big feast turtle egg.” Late in the afternoon we returned empty handed.

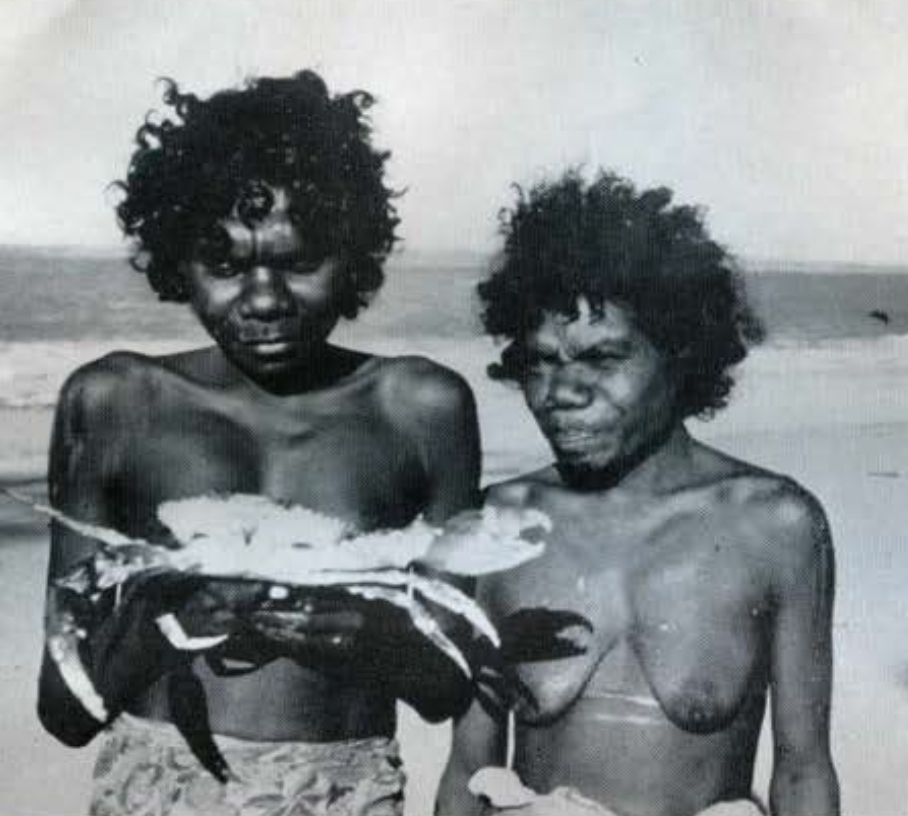

Fortunately Big Jack, hunting along the little, mangrove-lined creek close by, had not had such bad luck. He soon appeared carrying three of the large mangrove crabs, their massive claws tightly closed with bindings of bark strips. The two main logs of the noon fire were still smouldering, and by adding to them we soon had a fast-burning blaze. When a glowing bed of coals was available, the crabs were thrown on top where they were soon steaming away in their own juices. It was a delicious supper-tender, sweet crabmeat, lukewarm tea, and the remains of the fresh bread smothered in jam for dessert.

Image Number: 67909

The sky by this time was growing dark for thick, heavily laden clouds were fast building up. With what light remained from the setting sun we shifted camp to a small hollow in the dunes, free from the prickly seed pods and protected from the wind. Soon it was quite dark and the wind seemed to blow more strongly. Albert, afraid for the safety of the canoe, decided to remove it to the quiet waters of the little creek where Big Jack had found the crabs. Big Jack accompanied him and while they were gone Agnes prepared to make some “damper.” She built the fire up again so that the ground would become very hot. While it was burning down she took the bag of flour, opened it, and made a small depression in the contents. Into this hole she poured baking powder, salt, and water from the billy. (Quite often the first two ingredients are omitted.) With both hands still in the bag she worked the mixture into a large lump of dough which she removed and flattened on the outside of the flour bag. By this time the fire had again burned down, and the burning coals were brushed aside and a hole scooped out in the hot sand. The damper, about the size of a large frying pan, was laid in the hole and covered over with more hot sand. “Tomorrow, we make quick breakfast and no stop for lunch,” she explained. In about an hour, during which the damper had been turned once, it was removed and the sand brushed from the rough, tough surface. It was then carefully wrapped in a piece of calico and put away in safety.

It was only then that we realized that the men had not returned. Agnes became quite worried, and I must confess I did also. We walked down to the water’s edge and called out, but could hear no reply over the roar of the waves, and because of the inky blackness we could see only a few yards. After about ten minutes we returned to the camp and in a brief time both men appeared. Agnes immediately demanded to know why, if they were so close, they didn’t answer our calls? Albert insisted that he had replied, so after a while Agnes changed her question to why had it taken them so long? “Water bin come in long way,” Albert replied, “I swim out; take long time find him canoe.” When one considers that, together with sharks, these waters contain the large and dangerous salt-water crocodile and all manner of poisonous jellyfish, one realizes that to swim around in a high sea in the pitch dark requires considerable courage.

Soon after we had crawled under the mosquito netting and between the blankets rain began to fall in a gentle and persistent way, but still not hard enough to prevent our falling asleep with little conversation.

Image Number: 67910

It was hardly light the next morning when Agnes stood up and rewrapped her naga, a strip of calico, about her waist, then took up the billys and went to the well to draw water for the morning tea. Although the rain had been steady during the night, the well-built fire still had some life in it and after a few minutes of concentrated blowing, Albert had it rejuvenated. While the billy boiled, Big Jack shook as much of the wet sand as was possible from the blankets and rolled them into tight bundles. Then he set off to retrieve the canoe. By the time he reappeared, the tea was ready and it helped to wash down the leathery cold strips of damper sweetened with jam.

Although the wind had died and the clouds given way to a clear, light blue sky, the sea still had heavy rollers. However, instead of breaking over the canoe, they gently lifted it high in the air, then let it slide down the incline. We set out as the first rays of the sun appeared over the horizon and soon began to feel revived as our clothes began to dry. \Ne stayed fairly close to the shore, close enough so that landmarks could be easily seen. For a while we coasted by the thin white strip of sand along which we had hunted for turtle eggs the afternoon before. The land in back of the beach was low swampland and all that could be seen was a thin line of green foliage. But soon we approached Tubinu Point. H ere the beach gave way to a jutting headland and the steep seaward cliff was a rainbow of colors where bands of ocherous clays of yellow and red were separated by clear white and topped by a heavy line of dark humus. Tall eucalyptus trees stood right up to the edge of the 75-foot cliff. We stayed well clear of the base, for a short but ragged, rocky reef extended out under the water.

Image Number: 67911

Rounding the point, we came to a small inlet edged with the ever-present tangle of mangrove trees, beyond which was another clean white stretch of sandy beach. About this time the puppy grew restless and started roaming the canoe from stern to bow. Once he had reached the bow he climbed up to the very point and stuck his nose into the wind. As the canoe rose and dipped he would Jose his balance and I would grab him and hand him to Agnes. But he would not stay put and soon would again be a live figurehead pointing the way. Finally, Albert said, “Let him go.” As was to be expected, the next roller knocked little Tchuwiunga off his perch and into the sea he went. As the canoe passed, Albert leaned over and fished the frightened, struggling puppy out of the water and handed him to Agnes, who began rubbing him down. “Him gotta learn,” remarked Albert. “Sea bin teach him more better.” Soon Tchuwiunga revived his courage and again ventured forward, but this time instead of standing on the bow he curled up on the bag of flour and slept soundly until we reached our destination. He had indeed learned his lesson well.

The rolling motion, sun, and inactivity had made both Agnes and me drowsy and we were all but asleep when Big Jack woke us with, “Black Joe mob. Him camp Anderaningo.” I looked in the direction to which he pointed with his chin, but could see nothing other than white sand broken in spots with the heavy green of the mangrove jungles. “There,” he repeated. “See. Him make big smoke.” By straining my eyes and imagination l believed I could see a tiny wisp of white smoke rising above the last patch of green on the furthest point of land.

Image Number: 67912

Distances were deceiving, for the point of land which seemed so many miles away was soon reached. The entrance to the Paluwiunga River was a narrow channel cut through the far edge of a broad sandbank. Rather than circumnavigate the bank, the men decided to go over it, but as the waves breaking over the sand were churned into a tangle of white water by the opposing river current, it was deemed advisable that all surplus passengers disembark. Agnes, clutching the puppy, and I, with my KLM bag, jumped overboard into shoulder-high water and slowly made our way over the bank to the shore. The men also went overboard and, with one on each side, they guided the canoe safely to the quiet water of the river. For a while we all stretched our legs walking up the sandy bank of the river until mangrove roots stopped our progress.

Once back in the canoe, Albert took over my place in the bow and with his fish-spear poised he kept a watchful eye on the deep green waters. Once he spied a barramundi and cautiously directed Big Jack to paddle towards the large fish, but it glided out of reach.

About a half mile up the river we came upon the shaded glen of casuarinas, another camping spot with its fresh-water well, named Anderaningo. Here instead of Black Joe’s mob we found the Superintendent, Bill Grimster, his son Billy, and two natives, Billy-Two and Brownie. Black Joe’s mob had arrived the afternoon before and had been ferried the ten miles up river to the next camping spot in the motor launch. Bill Grimster, having been told by Black Joe that he had seen our smoke near Piriu, knew that we had camped there, and he came back down river with an invitation for me to join them for a night of crocodile hunting before they returned to Snake Bay.

Image Number: 67913

For many people in this area, hunting the large salt-water crocodile is a profession or a sought-after sport. In both cases it is dangerous, for this particular species of crocodile is intimidated by nothing and frequently will attack men or beasts without provocation. The crocodiles, which often measure twenty feet in length, occupy a prominent place in the myths, legends, and art of the Tiwi, and many are the true-life tales of people who have lost their lives in battling these beasts, which are hunted by the natives for their meat and valuable skins. When one considers the size of the animals and the size of the canoes, it is no wonder that Bill had discouraged any requests of mine to accompany them. So this invitation was a most welcome and pleasant surprise.

I transferred to the launch for the up-river camp so that f would be in time to leave on the hunt at dusk. For the first six miles the river wound seemingly aimlessly through the deep, dank, and mysterious mangrove swamps. At times the branches almost met across the water, brightly colored birds flitted from branch to branch and a subdued splash indicated a crocodile disturbed from his afternoon slumber on the muddy bank. Adding to this almost evil atmosphere were strange clacking and sucking noises emanating from the impenetrable jungle, which were attributed to the Ningawi, the weird and mysterious “little people” of the mangrove. Rounding a curve in the river, we surprised a flock of whistle ducks sitting on an exposed mudbank. Young Billy tried to shoot one for supper but missed, and soon they were well out of range. On a rare piece of solid ground we saw the long tail and massive hips of a startled wallaby as he hopped to safety. However, a successful throw of the fish-spear brought us a large barramundi, and the .22 rifle provided both a possum and a fruit bat, or flying fox, for supper.

All of a sudden the mangroves disappeared and our view was no longer restricted to the river bank; rather we gazed through thick, gnarled white paperbarks on the water’s edge to wide expanses of marshy grasslands. A few flocks of black and white geese, which had returned to the swamps early in the evening, were startled by the sound of the motor and rose honking in fright.

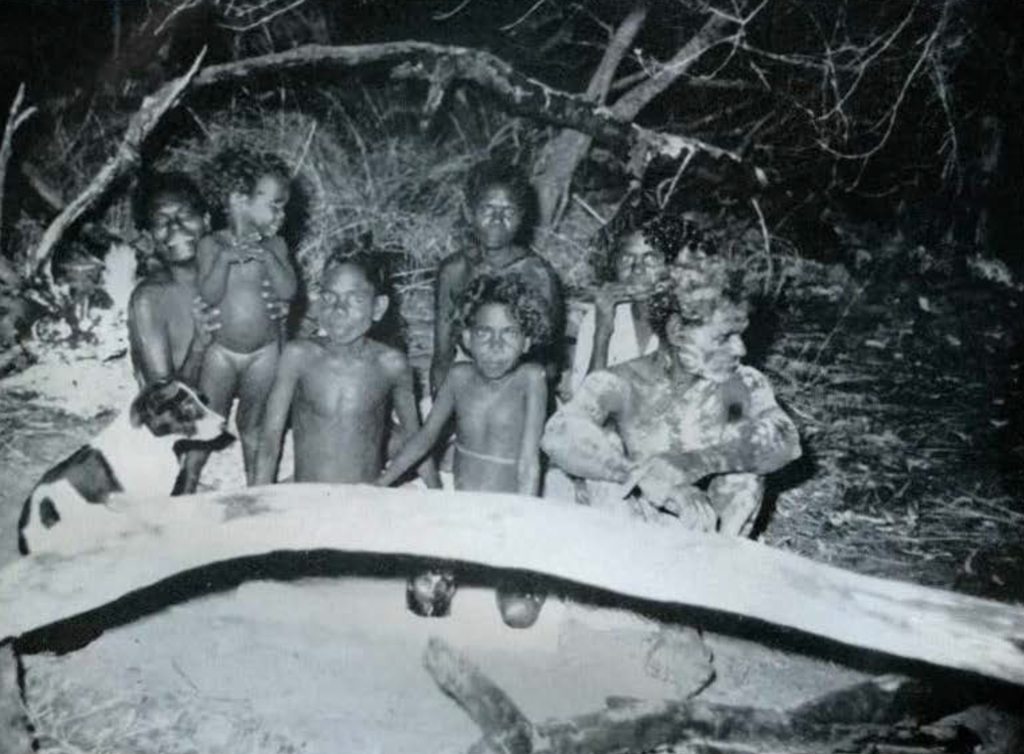

Image Number: 67914a

About five, we reached Minianapi, a landing place about fifteen yards wide, where solid ground reached the river bank. We were met at the water’s edge by Black Joe, his wives, Margaret and Filicy, their two children, Dennis and Crissy-Boy, and the rest of his party numbering about twenty. Since it was already growing dark, we made a hasty supper and were soon back in the launch ready for the night’s hunt.

I sat in the stern of the 15-foot boat with Bill Sr., while young Billy sat by the motor in the center holding the battery-powered searchlight. Brownie and Billy-Two were in the bow close to the long, heavy, iron-tipped harpoons. As we continued up river, I was carefully instructed as to what I should do. My instructions were to do absolutely nothing, not move, speak, whisper, nor hardly breathe once the signal had been given that a croc was sighted. Soon it was very dark, the stars were blotted out by heavy clouds, and it rained heavily for a short time. After a while, young Billy, who had been swinging the light slowly from hank to bank, said softly, “There!” and held the light steadily on the left bank. Immediately Bill shut off the motor and both he and Brownie took up paddles. Billy-Two meanwhile had eased himself up so that he stood straddling the bow, a foot on each gunwale. The harpoon was poised above his shoulder ready to throw. Extremely slowly and without a sound we approached the two shining red disks, the croc’s eyes, held transfixed by the powerful light. When will he ever throw, I silently wondered; but it was not until we were within two or three feet that Billy-Two lunged forward and thrust the harpoon deep into the crocodile’s back. Suddenly the silence was broken; Billy-Two wrenched the harpoon shaft loose and laid it in the boat, taking up instead the rapidly-disappearing rope attached to the iron barb. The crocodile sounded and began swimming under the boat. Young Billy gave the light to his father and took up the shot-gun. Brownie helped Billy-Two pull in the rope and suddenly the water broke. The light and shot-gun were aimed and almost simultaneously a shot struck the grotesque head; soon the animal was dead. All hands then heaved and the 14-foot crocodile was laid to rest at our feet.

Image Number: 67915

The night was young, so we continued up river. After a while the moon broke through the clouds and silhouetted the white paper-barks. The river grew quite narrow and wound through a succession of mirror-black pools dotted with water-lilies and criscrossed just under the surface by the massive roots of the paperbarks. It was in just this sort of pool that the largest of the five crocs landed that night, was harpooned. The huge 18-foot animal dived into the roots and it took about twenty tense minutes to dislodge and dispatch him. Aside from the crocodiles the only wild life seen that night was a small and very frightened little mouse who suddenly appeared on my lap and then just as suddenly disappeared over the boat’s side.

We returned to Minianapi at daybreak and the hot tea and roast goose seemed a perfect breakfast, or was it supper? It didn’t matter for we were soon sound asleep.

When we finally awoke in mid-afternoon we found the camp almost deserted . “Everyone go walkabout; kill geese,” Albert informed us as he and Agnes gathered more wood to build up the smouldering fire. It was very quiet in the small clearing and only the little black spots of charcoal spaced in irregular intervals on the ground were evidence that there were more than our mob in residence. The clearing itself was quite bare because it had been burned by the first comers, with the double purpose of clearing out the four-foot grass itself, and any of the various poisonous snakes which were quite likely to infest it. In back of the clearing was a thick tangle of low bushes through which ran a little foot-path. Agnes started down this path carrying a billy can and I offered to go with her, but Albert said, “No, by um by we go, him long way, him only get a little bit now.” After one gets used to the pronoun “him” being used to refer to everything animal, vegetable, and mineral, this phrase is perfectly understandable: the first “him” referred to the water, the second to Agnes.

Image Number: 67916

So instead of collecting water, I wandered down to the river bank where Billy-T wo, Brownie, and a few of the other men, were busy skinning the crocodiles. This they did by cutting the skin first around the head, then down either side of the rows of bumps running along the spine to the tail. The skin was then carefully peeled and cut from the body. Once free it was rubbed with salt which would act as a preservative until such time as the supply boat would arrive to carry it to Darwin. There the skins would be sold to the dealer and the proceeds credited to the hunter’s account or sent in the form of hard cash to the settlement for distribution. Now they were folded into bundles and loaded into the launch, and large pieces of the white meat were carried into the camp to be roasted for dinner. What was not to be consumed that night was thrown into the water, for meat spoils quickly in this sticky climate.

Darkness came early, and with it came the return of the goose hunters and the departure of the launch with the Grimsters and their crocodile team. Once more they would spend the night hunting crocodiles, this time downstream on their way back to the settlement. Soon many little fires broke up the darkness of the clearing and the smell of fresh roasting meat wafted over to where Albert, Agnes, Jack, and I were opening cans of corned beef. “Tomorrow we go bush,” Albert remarked and I heartily assented.

Young Brook, a lean young man, and his wife, Alice, approached our fire. “You savey goose?” he asked me. “Oh yes,” l said, “we eat him along America.” He handed me a large juicy leg which I gave to Albert to divide, then squatted clown at the edge of the fire’s glow. I handed my tin of tobacco to Alice and she filled her husband’s pipe. Picking up a burning branch from the fire, she knocked a hot coal into the bowl of the pipe and began smoking. Soon she handed it to Young Brook. Suddenly our attention was directed to the opposite side of the clearing where Dennis, the four-year old daughter of Black Joe was crying hysterically. Tuki, a tall powerful man of fifty-five, was doing his best to calm her and disentangle himself from her clinging arms so that he could leave. Tuki and his wife, Fat Alice, were a childless couple and Black Joe, Fat Alice’s brother, had given them his eldest daughter in adoption. However, Dennis spent as much time with her proper parents as with her foster parents and it was quite evident that her affection was at least equally divided. Albert went over and managed to bring the screaming, kicking child back to our camp and asked me to give her some of the hard candy which I had brought with me. It was some time, however, before her attention was sufficiently distracted to allow Tuki and the other men to slip away into the canoe to hunt crocodiles for another night. Agnes commented to me, ” Let him cry? That white man rule no good. By and by they go silly.”

Image Number: 67917

We strolled back to Black Joe’s camp with Dennis, and listened to a discussion concerning the superiority of crocodile hunting over settlement work. It seemed the chief advantage was that they received ‘money-in-the-finger’ from the skins they caught. They didn’t understand why they didn’t also get paid for the settlement work. I kept silent, but soon they turned to me and said, “You get job; how much you pay?” I told them, and then went on to say that out of that salary I had to pay someone for the food I ate, the clothes I wore, the house I lived in and so on, whereas they did not have to pay for the flour, tea, sugar, meat, blankets, or clothes the welfare people gave them. There was a long silence during which, I believe, each man was figuring how much all these benefits were worth in hard money. Finally Ginger said slowly, “Maybe, this way more better.”

Soon the visitors rose and returned to their fires. Someone started a song, a low nasal chant. Another, a woman, began a high- pitched love song, and to this discordant lullaby I soon fell asleep.

As usual, it was barely light when the camp came to life again. After the customary tea breakfast, the various families discussed among themselves the day’s plans. Black Joe and Long Peter, their wives and children, were taking the canoe up-river to hunt. Young Brook and his brothers. Danny Brown and Charlie Cook, their wives and children, soon left to hunt in the area back of Minianapi. Charlie Quiet and Roger also left. ” Now we go?” I turned in question to Albert. “No, we stay behind. Build house. No good you go bush. Too much grass, plenty big mob cheeky snake. By and by that mob burn grass; then we go bush.” It seemed like a logical explanation, but I was disappointed.

Image Number: 67918

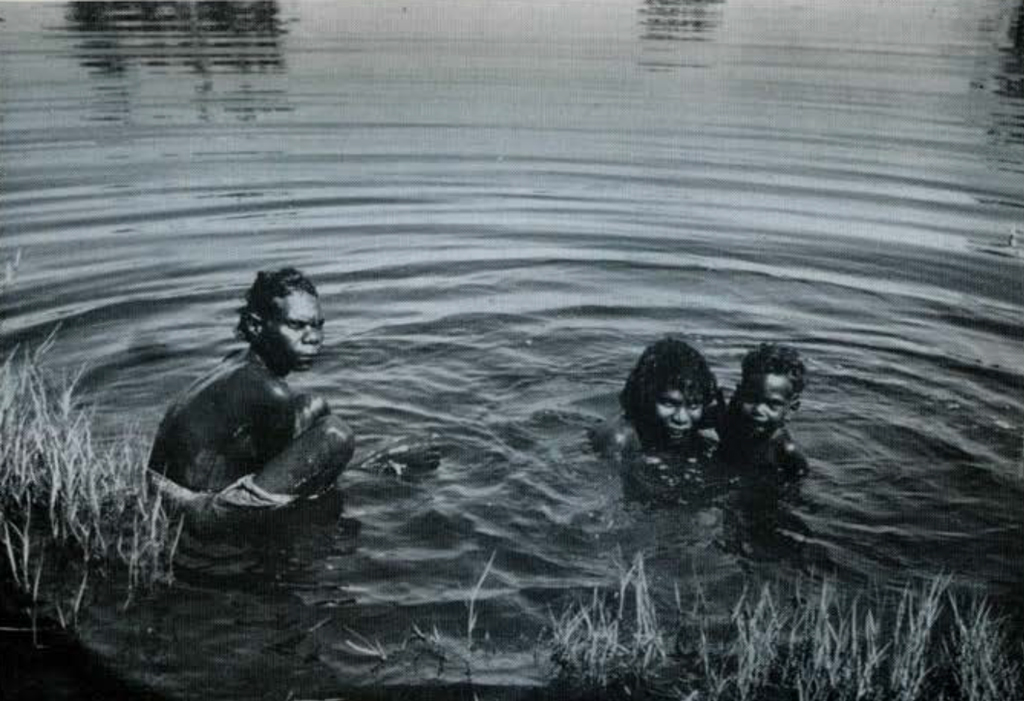

The day was already sticky and muggy, and tired of inactivity I started off toward the creek, saying I was going for a swim. Both natives jumped up and said, “No. No. Too much crocodile, more better go along billabong.” So with Agnes ahead we started down the path leading away from the creek. Soon we were out of the thick tangle of bushes separating the clearing from the true bush. Now the path led over the rocky, dusty ground, which had but recently been burned. The trunks of the large bloodwood and stringy-bark trees were blackened for about four feet up from their base. The spiraled trunks of the screwpalm, as well as their lower dried leaves, also had a charred appearance. Except for an occasional patch of grass, which the rushing fire had missed, there was not a living green plant below the four-foot line. Burning the country is an annual occurrence and many are the laws governing who may burn and who may subsequently hunt in the newly cleared land. Because the fires are set each year, there is no accumulation of dry tinder to feed the fire and allow it to rage uncontrollably. Only the grass and a few fallen logs catch and these will burn rapidly and fiercely, but for a very short period. Any gap in the vegetation will stop the fire and the heavy dew, falling in the evening, will also put out the flames, leaving perhaps only isolated, smouldering logs to burn through the night. Until the first shoots of new grass push their way through the charred ground, the individual hunter who set the fire has exclusive rights to the area he set alight. Of course, no one except those who belong to that country may burn without permission of the owners. As far as possible, these laws are still upheld.

We soon came to a branch in the path and Albert indicated that we two girls should continue straight ahead; he would stop behind. In front of us stretched the fresh-water swamp. Out of the almost inky but clear water rose the gnarled paperbark trees, their roots so intertwined they almost formed a floor, albeit a most slippery and irregular one, over the rotten vegetation in the bottom of the swamp. I picked a particularly large rooted tree for my bath tub, and a short distance away Agnes did the same. If one was careful not to disturb the fine deposit on the bottom but managed to stay on top of the slippery roots, the clear cool water was as sweet and soft as one could wish for. We stayed for about an hour, washing ourselves and our clothes, but finally an impatient call from Albert put an end to this pleasure. Albert had been hunting for a possum, but in this area so close to the camp, they had already been depleted.

Image Number: 67919

Instead of returning to camp, Albert decided that now was as good a time as any to cut his milingani, the sticks with which they kill the geese. After another mile or so into the bush, we came to a grove of stout bushes of a kind I had not seen before. They had long, straight branches of about a half-inch diameter. These Albert cut and after he had collected about thirty he selected a nice, smooth ledge of rock in the shade to work further on the sticks. First he stripped the bark, then measuring them against his arm he cut them so that each stick was as long as the distance from his fingertips to his elbow. All this he did with his knife, holding it by the tip of its long blade so that the handle would add its weight to each blow. He carefully smoothed off the two ends so there were no loose splinters. We each took a bundle of these sticks, tied them with strips of pandanus, and returned to the camp. Here they were laid in the water close to the bank and weighted down with a rock. This would make them good and heavy, it was explained.

During the afternoon, the two men worked on the permanent house which Bill Grimster had ordered. Big Jack had spent the morning cutting posts and had brought in about half a dozen. By late afternoon, when the others returned, they had been set upright in holes dug to individual measure so that they stood firm without bracing.

Once everyone had returned, a fire was built. The men collected their individual bundles of milingani and placed the ends of the dripping sticks in the flames. They squatted over the sticks and individually started a chant during which they cupped their hands in the smoke and carrying it to their bodies, slapped their necks, then their arms. “Knar. Knar Gerra doo (slap), Gerra doo (slap).” The chant was nothing more than the imitation of the cries of the geese and the whir of the sticks. They explained that to bring the goose down they had to hit it directly on the neck or wings. “Why do you cook the sticks?” I asked. “To make them dry so they won’t slip in our hands,” they replied.

Image Number: 67920

Once the sticks were all well charred on the ends the men took them down to the canoe. For once, I used my status of ethnographer and overruled my role of a woman, and accompanied the men on what was properly men’s business. The presence of women or children might bring bad luck. Whether the explanation was simply that women and children are considered to be lacking in the amount of silence or immobility required, or whether the reason was more subtle, I never found out. “This properly men’s business,” was the only explanation.

We took the canoe a quarter of a mile up stream, where we disembarked on the edge of a large expanse of wet, grassy marsh. On the bank a few low trees provided cover for the hunters, who spread out about fifty yards apart. We waited. Then in the distance the first flock of six geese appeared, flying low over the marsh. They were not headed for us, but passed over the line of hunters about a hundred yards upstream. We could not see the hunters, but the same six geese continued safely after passing the firing line. Now another small group of geese seemed to be heading in our direction. Albert slowly took his position, his legs apart, the left stretched in front, the right somewhat bent as his body arched backward. One milingani he held near the charred end in his right arm which was so far back over his head that the tip of the stick almost touched the ground. As counter balance, his left hand, holding several spares, was pointed forward toward the geese. Just as the geese were to pass over our heads, they swerved and went instead over the man to the right of us. You could hear the whir of the stick as it was thrown with tremendous force up into the air, turning end over end, and then the ‘thwack’ as it reached its mark. A goose, its neck hanging loosely, spiralled down, to land with a splash close to the hunter’s feet.

Now the flocks were more numerous as the dusk grew thicker. Soon a group flew directly overhead and Albert aimed and threw, but the spiralling stick slid off the wing tip of the lead goose and he continued, somewhat shaken but quite unharmed. Again and again Albert threw at the increasing numbers of honking homeward-bound geese, but when the last stick was thrown and it was quite dark, we still had no geese. When we gathered, it was found that out of ten hunters with perhaps three hundred sticks thrown, only two sticks had found their mark. This was not good. Albert was worried. “Maybe someone bin die, make me bad luck.”

Image Number: 67921

Later that evening Black Joe started singing a chant. “Mobuditi, plenty goose here; give us some.” I asked him whom he was singing to and, although names of the dead are most infrequently mentioned for fear that the ghost of that person, its mobuditi, will hear it, this was one occasion where the mobuditi could do more good than harm. So the mobuditi of Bangri was called upon. Bangri, it was explained, had been a big man, “Plenty wives, maybe hundred. This his country; him grave close up along bush. He bin die long time ago.” This had been his country while alive and it was still his country, for his spirit remains near the grave and still hunts the wild animals and birds, while the spirits of his wives collect the wild yams, and his little spirit children play in the bush. Bangri will share this food with others who come, and their mobudities, should they die and be buried in the country, for as long as his name is remembered, and until his grave-posts rot with the passing of time.

But Bangri was not cooperative. The next day the hunters found little game in the bush and the women turned to the laborious job of digging six-foot holes with a stick to obtain the small yams that are to be found at this season. Again the grass was too thick, the snakes too cheeky, and Albert advised against our going bush. I decided the more logical explanation was that Albert considered we ourselves had ample food, and besides he was sincerely worried about his long run of bad luck. But he left with the others that evening to kill geese. When they returned with only three geese, a long conference was held. I offered all the food I could spare and it was decided that, in return for a few yams and some of the goose, l should make dampers and put jam on them for the children, all of whom were under five and very hungry, and give small pieces of tobacco to the men and women. This was Albert’s, Agnes’s, and Big Jack’s tobacco, and so everyone trad ed something and all pronounced it a fair deal. I cooked the damper, smothered it with jam and, with Agnes prompting, called, “Kakritjui Kali.” “Little ones, come.” The five who could walk, ran, then stood shyly by while I handed each a piece; then they ran back to their mothers. Soon they were back and, nudged by their mothers, all murmured “Thank you very much.” This was a phrase I never heard, either in the native language or in English, when they were receiving from another native. Giving and receiving were so much a part of their life that among themselves “thank you’s” seemed unnecessary.

Image Number: 67922

The following day we finally went hunting. Peter, his wife Dorrie, and daughter Althea, Filicy and her son Crissy-Boy, Albert, Agnes and I all squeezed into the canoe and paddled about two miles upstream to the next landing. Tudiunginarim, “white-paint-place,” used to be an old camp of the white buffalo shooter, Joe Cooper, who at the turn of the century was the first white contact for many of these people. It was very hot and the women took their children into the water, waist deep near the bank, for a swim. It was easy for them in their nagas, for when they came out they merely wrapped a dry one around and slid the wet one off underneath very modestly. I, in my shorts and shirt, finally gave in to the temptation and, vowing that if I were to live here longer I would take up the native costume, went in fully dressed. This modesty was a funny thing; they who wore no clothes until contact with white men, were being modest only for my sake, and in return I could do no less. So with dripping clothes, which incidentally felt wonderful in the heat, I set off following Albert and Agnes.

The nature of the bush was the same as that in back of Minianapi and indeed the same as that around Snake Bay: the same trees, the same burned earth, the same fan palms and pandanus, and the same flatness. The natives always knew where they were; I never did. We were looking for possums and as these furry marsupials sleep in hollow trees during the day, we investigated every likely tree for evidence that they had recently climbed it. Sometimes the little tears in the rough bark could only be seen silhouetted against the sun; at other times the dry ground around the base of the tree would show very definite tracks. Soon Agnes, who was off somewhere to the left of Albert and me, gave two high-pitched calls. In the hunting language I had already learned, one call meant “I’m here, where are you?” and would be answered by their companions with a similar single call. However, two calls meant “Come; I’ve found something.” So we turned in the direction of the call and soon found Agnes standing by a short, hollow tree. Albert took his axe and cut a long pole which he then thrust up through a hole in the tree’s base and wiggled. Out popped a large grey possum which sat on the top of the tree trying to make itself as small as possible. Agnes and Albert threw all manner of sticks and stones at it and finally managed to knock it down, when it scuttled away. It was soon overtaken by Albert who killed it quickly with a blow from a stick. As he brought it back he said, “Him big mother. See him pickaninni.” And he held up a hairless baby barely three inches long, its eyes still closed, but very much alive. “Oh, kill it quick, Albert,” I begged. He shook his head, “I can’t kill him, I too sorry alonga him.” Here we were at an impass, two people too sorry alonga him; one too sorry to kill it, and one too sorry to let it live. Who was right?

Image Number: 67923

Meanwhile, Agnes took the mother possum and pulled the fur from a small area on the belly and then slitting the skin with the sharp end of a broken stick, she withdrew the gall bladder and intestines. “Him make him bad,” she explained. We did not stop to cook the animal, but continued our search. This area had all been burned by the previous parties and already little delicate shoots of grass were poking up through the black ground.

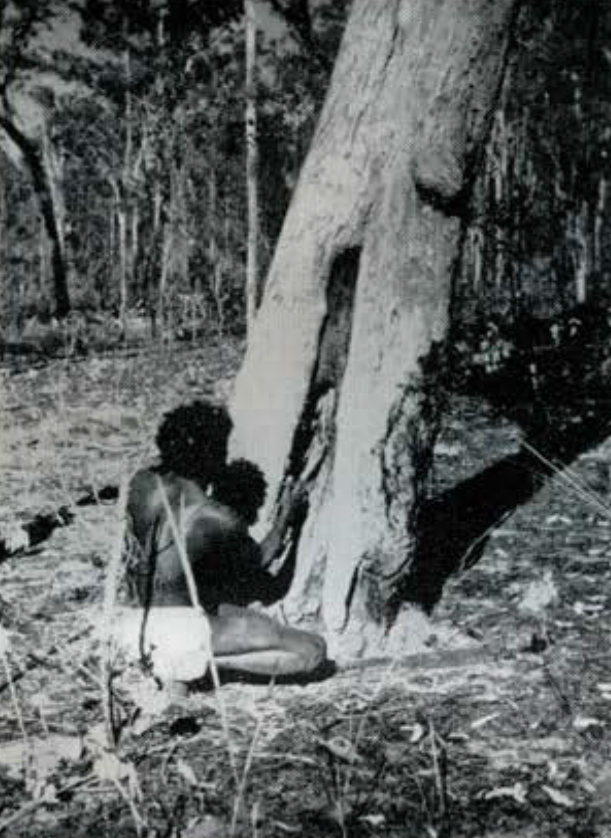

During the next hour we wandered slowly through the bush and, although we saw many trees which had been inhabited by possums, they were now empty. One that looked most likely was hollow and Albert hopefully built a fire in the rotten base, then sat back and waited for the smoke to drive the animal out. After half an hour, it was quite obvious that no one was at home.

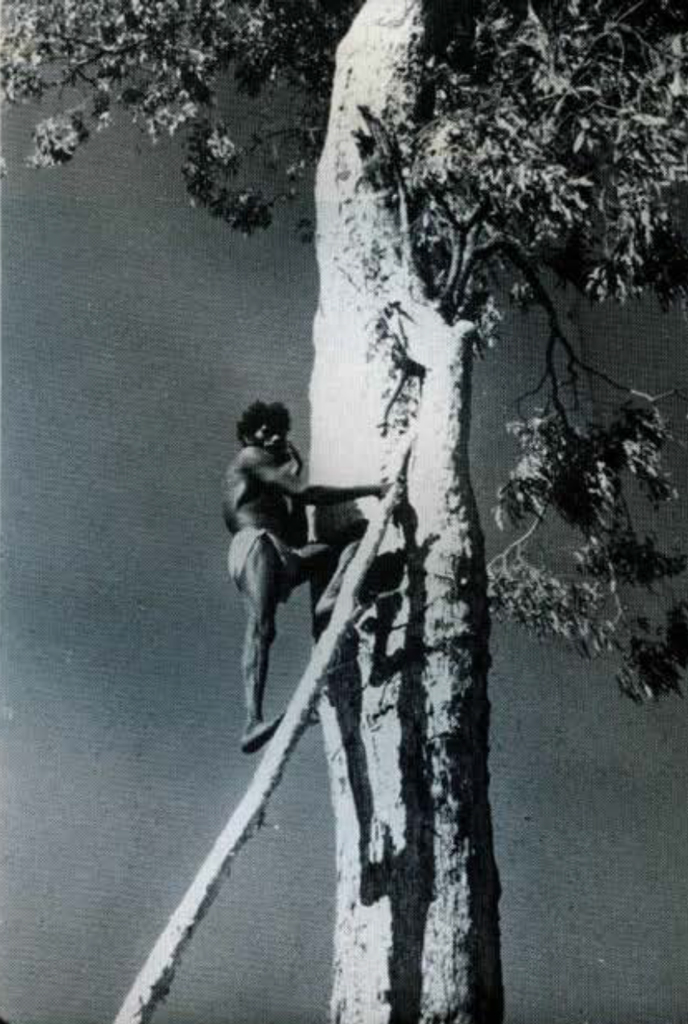

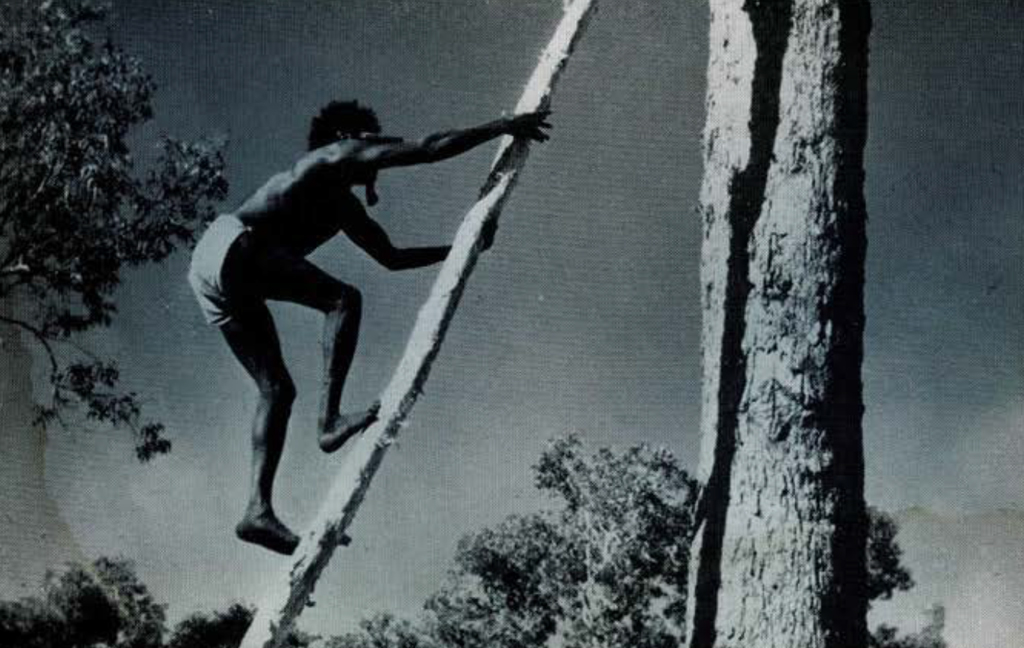

Then our luck turned. This time, when Albert gave the “come here” call, it was because he had located a wild honey nest, or “sugar-bag,” high in a large stringy-bark eucalyptus. There was little point in cutting this large tree down so Albert prepared to climb. First he cut a small sapling and laid it at a 45-degree angle against a crotch where the massive trunk split in two. Then, gripping the axe with his teeth, he ran up the sapling on all fours with as much agility as a monkey. Upon reaching the crotch, he put his arms around the trunk, placed the soles of his feet close together against the bark, and quickly progressed in a sort of leaping motion up to the top of the tree. Once there he casually climbed up, over, and around the various branches, until he reached the object of his climb, the hollow branch with the little hole through which was passing a steady stream of small insects. This branch was quickly cut through and fell crashing to the ground. Soon Albert was down again, investigating this find with Agnes and me. The hole was enlarged and the combs of dark honey exposed, still crawling with the little black bees. We dug in with our fingers or brushes made by chewing small twigs, quite unmindful of the bees, who obligingly never developed stings in this part of the world. The honey was dark and very strong, but when mixed with the dry, crumbly, yellow “bee bread” a nice balance of taste was obtained. It took the three of us very little time to finish the sugar-bag and off we went-this time in a homeward direction.

Image Number: 67924

The one possum looked very small and Albert again began muttering about “someone mobuditi make me bad luck.” We separated again and when almost to the creek Agnes suddenly held me back and cautioned silence. Carefully she picked up a stout stick from the ground and then approached what I suddenly noticed was a very fat goana, about two feet long, apparently sound asleep on a nearby tree trunk. One quick blow and the lizard fell to the ground, quite dead. We carried the catch to the landing and quickly had another swim before Albert caught up. We were gathering firewood when Albert arrived and explained his delay by holding up another possum. The second possum was immediately gutted, then both were laid on the fire and turned frequently until all the fur had been burned off and the skin made brittle. The animals were quartered and laid again on the fire until well roasted. The goana received no preliminary treatment before going on the fire. When all were cooked, they were removed and laid on a “table” of clean, green leaves, and we reached in and tore off pieces of the steaming, juicy meat. It is impossible to describe this meat to someone who has not tasted it. All l can say is that it was tender and tasty and perfectly cooked, with that delicious charcoal-broiled flavor so much sought after in our more elite dining establishments or in our backyards.

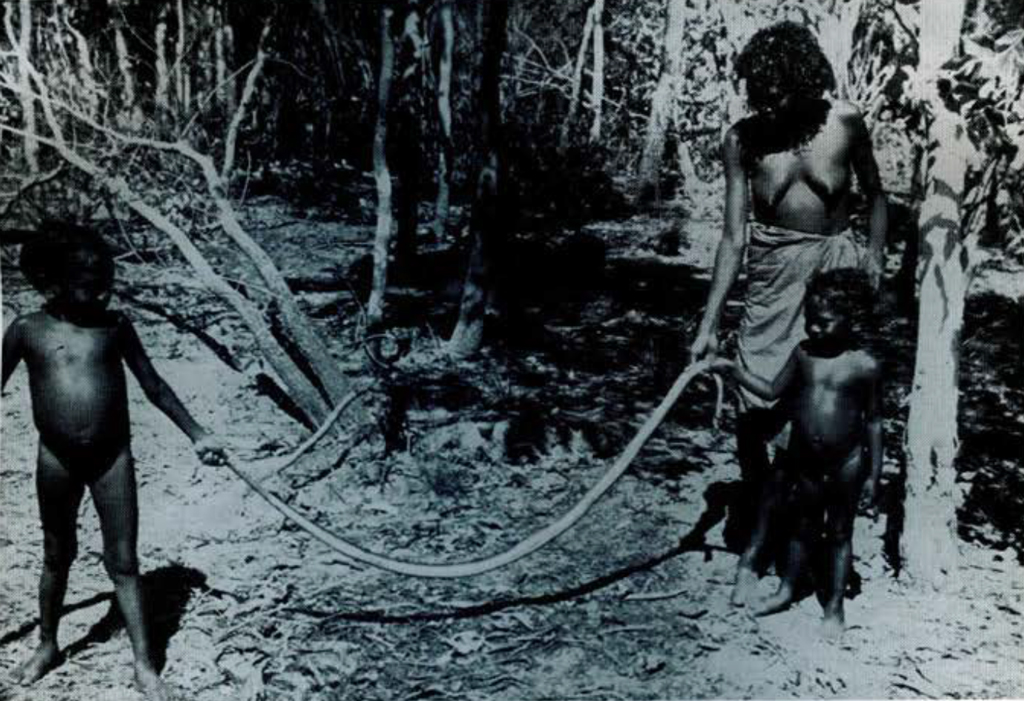

Just as we had started our feast the other group arrived and soon had their fire started. Although no overt comparison of each other’s catch was made, it was quite obvious that their hunt had been more successful. Besides the half dozen possums and two goanas, they brought over to show us an extremely large water snake about ten or twelve feet long. Shortly, Filicy again came over and presented us with one of their possums. After this tremendous feast, everyone stretched out and went to sleep, rousing only in time to arrive back at Minianapi in time to meet the geese. All the way back in the canoe, Crissy-boy played with two hairless baby possums, creating quite an uproar as he put them in everyone’s hair where they clung with their tiny feet. They died before we reached the shore and were thrown into the water. Althea was equally entertaining as she sang some risque love songs she had picked up around camp.

The evening’s goose hunt was even more unsuccessful than the earlier hunts. Two of the men separated and went down river and killed three geese, but the others, upstream in the usual place, did not even see any, and there was more talk of mobudities by everyone way into the night.

The following day was the last and, as the Assistant Superintendent was due that evening, feverish work was done by one and all on the long neglected house. Evidently the arrival of Paul scared off the ghosts, for that evening we almost had a goose per person, and my final memory of Minianapi is one of flickering fires in the moonlight and the smell of fresh roasted goose carried on the gentle breezes.