Beth Shean (“house of ease”), ancient NysaScythopolis, sits on an important crossroads in the Galilee and is watered by abundant springs. It is known variously as Beit She’an, Bet She’an, Beth-Shan, Baysan, or Beisan — the name can be transliterated and spelled in a variety of different ways.Occupied as early as the 6thmillennium BCE, the site bega nto figure prominently in Biblical history around 1100 BCE when the Philistines conquered the Canaanite settlement,which they subsequently used as a base for their military operations in the region. The site is strategic in the battles of the following century, and is eventually retaken by King David when it became part of the Israelite Kingdom of David and Solomon. For this period,Beth Shean is mentioned in the Old Testament books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles. It fell to the Assyrians in the 8th century BCE, after which occupation was minimal.

Beth Shean reemerged as an important city in the Hellenistic period of the 2nd century BCE, when it became associated with the nymph Nysa, the nursemaid of the god Dionysos. It became part of the Roman state in 63 BCE and continued to prosper well into the Late Antique period; it became the capital of Palestina Secunda in 409 CE with a maximum population of ca. 40,000. The period 330–638 CE in Palestine is usually termed “Byzantine,” referring to imperial rule from Constantinople; the more general term “Late Antique” refers to the period of cultural transformation across the Mediterranean, ca. 250–750 CE. Indeed, LateAntique Beth Shean underwent a variety of profound political and religious transitions, including the advent of Christianity and the arrival of Islam — the latter with Umayyad conquest in 634 CE. The city was destroyed by an earthquake in 749 CE. Under Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, and Umayyad rule, the city sheltered a religiously heterogeneous population, as the material evidence abundantly indicates.

Penn Museum undertook excavations on the tell (mound) of Beth Shean in 1921 in expectation of clarifying the Biblical history of the site, as Jordan Pickett discusses in the following essay. This was the first American archaeological venture into the Near East following the breakup of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I. Palestine at that time was governed by the British Mandate and was no longer subject to the Ottoman’s stringent antiquities laws. Like contemporary colonialist ventures into Albania, Anatolia, and Iraq, the Penn Museum’s archaeologists saw this as a golden opportunity through which they could combine scientific exploration with significant acquisitions to expand the Museum’s holdings. In the end, the Museum added more than 8,000 artifacts from Beth Shean to its permanent collection.

The archaeologists in charge — Clarence Fisher, Alan Rowe, and Gerald Fitzgerald — were all trained in Bronze Age archaeology and were interested primarily in the early history of the site. As with the Museum’s earlier excavation at Nippur in southern Mesopotamia (1889–1900), in which Fisher also took part, both scholars and the general public were concerned with establishing scientific proof for the validity of the Bible. While the early finds from Beth Shean are noteworthy, the uppermost strata of the mound preserved substantial evidence of the Late Antique city, including a church of unique design, a small monastery, a domestic quarter, a synagogue, and extensive cemeteries. Nevertheless, the archaeologists found this material less compelling than the earlier layers. Consequently, the late material received scant attention and only brief publication. Major finds from their excavations are now divided between the Penn Museum and the Rockefeller Museum in Jerusalem. And while significant elements of the older periods of site occupation are on dis -play in the Penn Museum, more than 3,000 Late Antique and Byzantine artifacts are housed in the Museum’s storerooms, many of them unpublished, some still in their original packing crates. In addition, the Penn Museum Archives preserve the careful documentation of the excavation—including correspondence, daybooks, architectural drawings, photographs, and unpublished reports.

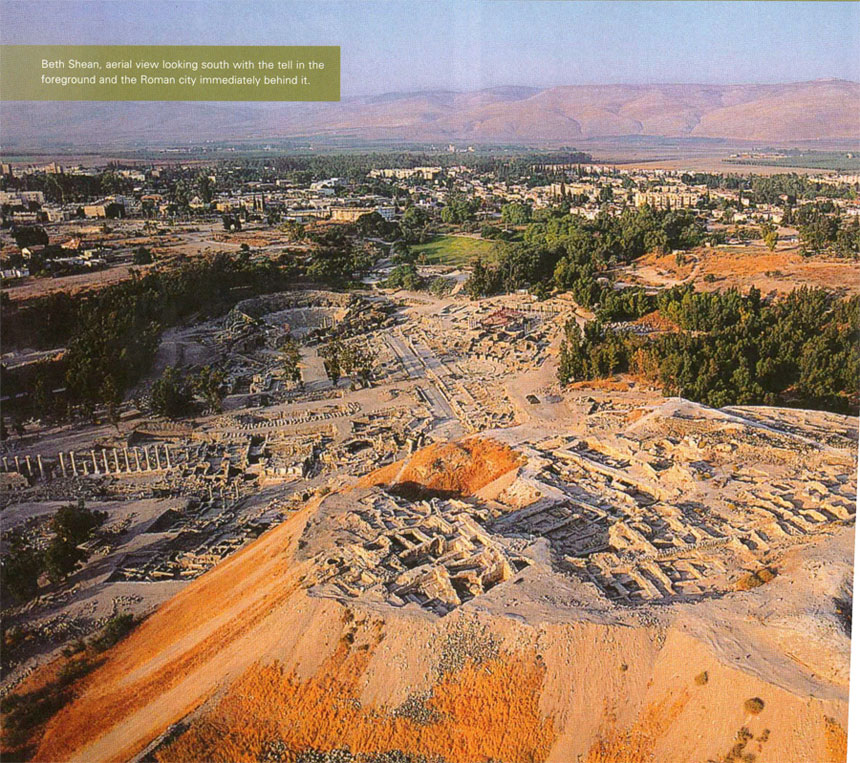

Beginning in 1983, archaeologists from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, armed with modern archaeological and research methods, reexamined the mound and conducted a major excavation of the Roman city at its base. In light of new discoveries and a refined chronology, not to mention the wealth of documentation at hand, Penn graduate students have begun to revisit the art and material culture of Late Antique and Byzantine Beth Shean, working firsthand with the artifacts and documentation in the storerooms and Archives of the Museum.

The brief analyses presented here testify to the rich and nuanced texture of life in Byzantine Beth Shean. Perhaps most striking is the endurance of pagan polytheism well into the 5th century CE. While Christianity assumed a dominant role already in the 4th century with Constantine’s famous Edict of Milan of 313 CE and his subsequent building program in the Holy Land, the survival of polytheist cults is noteworthy — long after the anti-pagan edicts of Theodosius, issued beginning in 381 CE, and close to the spiritual center of Christianity in Jerusalem. Indeed, the unique Round Church on the tell, discussed by Daira Nocera, may be contemporaneous with the Nysa figurines from the Northern Cemetery, deciphered by Stephanie Hagan. While the church may have replaced the Temple of Zeus, pagan worship continued, at least on a private level. Similarly, as Emerson Avery demonstrates, the proximity of Christian, Jewish, and pagan objects in the tombs of Beth Shean is remarkable and suggests a level of tolerance in the city and perhaps multiple religious affiliations within a single family. A similar blurring is evident in the floor mosaics of a small Christian monastery, discussed by Stephanie Hagan, where the same themes appear in contemporary synagogues. Finally, the blurred transition into Muslim rule—evident in the chronology of terracotta lamp production discussed by Geoffrey Shamos—underscores our misuse of religious conflict as an explanation for destruction. Clearly there are more lessons to learn from Beth Shean, as our continuing investigations demonstrate.

For Further Reading

Israel Antiquities Authority, The Bet She’an Excavation Project (1989– 91). Excavations and Surveys in Israel 11. Jerusalem: Israel AntiquitiesAuthority, 1993; English edition of Hadashot Arkheologiyot 98.

Mazor G. and A. Najjar. Nysa-Scythopolis: The Caesareum and the Odeum, Bet She’an I , Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority Report 33, 2007.

Rowe, A. Topography and History of Beth-Shan . Philadelphia:University Press for the University of Pennsylvania Museum, 1930.