In addition to Dr. Dales as Field Director, the official staff included the Museum’s architect Aubrey Trik and Stephen Rees-Jones of Queen’s University, Belfast, as Conservator. Helen Trik was Registrar and Barbara Dales was Administrative Secretary. Walter O. Heinze of Swarthmore served as volunteer photographer and field assistant for part of the season. The project was supported by the JDR 3rd Fund, National Science Foundation, the Penrose Fund of the American Philosophical Society, the Walter E. Seeley Trust Fund, and generous private donations.

One of the most intriguing aspects of archaeological research is the constant ebb and flow of our “knowledge” between fact and fiction. There is an ever present need to re-examine and re-evaluate the scattered bits of evidence with which we try to reconstruct the cultural framework of mankind’s climb to the modern world. It is not uncommon to find that yesterday’s “fact” is one of today’s discarded theories or that what is merely a calculated guess today may be a verified historical maxim tomorrow. Gradually this framework is strengthened and expanded as our factual knowledge of ancient problems increases.

Archaeology has had to expand its scope far beyond that of the traditional “dirt” approach to antiquity. More and more we hear of non-archaeologists, especially natural scientists, offering new insights into what were difficult or insoluble archaeological problems. These extra-archaeological specialists are increasing our ability to understand the broader significance of otherwise restricted and ofttimes esoteric questions. Just as a piece of three dimensional modern Op Art can be seen in its totality only by viewing it from many different vantage points, so must an archaeological problem be viewed from positions other than that of the dirt-archaeologist. The natural scientists can and are providing some of the desperately needed fresh viewpoints.

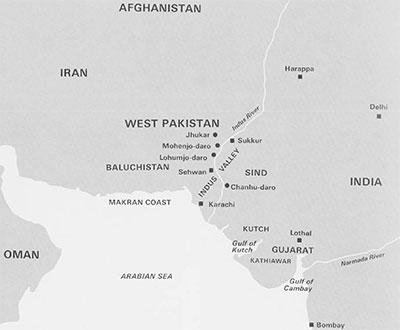

An example of the potentials inherent in combined archaeological-natural science investigations is seen in the field program carried out this past winter by the University Museum in West Pakistan. The Museum, with the cooperation and assistance of the Pakistan Department of Archaeology, initiated a program of excavations and environmental studies centering around Mohenjo-daro, some 180 air miles north of Karachi in the Indus Valley. The environmental and geomorphological studies were conducted by Robert L. Raikes, a professional hydrologist who has also collaborated with the Museum’s project at Sybaris in Italy. Among other questions of a purely archaeological nature we were concerned with the problem of why and how the Indus–or Harappan–civilization declined and eventually vanished. One explanation which has been popular in recent years is that this earliest civilization of South Asia “wore out its landscape” and so weakened internally that it became easy prey for foreign invaders–namely, the Aryans. The idea of a massacre at Mohenjo-daro which supposedly represented the armed conquest of the city was disputed on purely archaeological grounds by the author in the Spring 1964 issue of Expedition. Other factors in the collapse of the Indus civilization have come to the attention of natural scientists during the past few years. Preliminary studies by Raikes suggested that a great natural disaster–a series of vast floods– could have been a major factor. Fresh evidence was needed from the field to test these new ideas. Thus the program of archaeological excavations at Mohenjo-daro combined with geomorphological studies of the lower Indus Valley was initiated.

Mohenjo-daro was selected as the focal point of the project for several reasons. It is the largest and best preserved of the Harappan period cities in the Indus Valley and should provide the most complete sequence of stratified materials. The earlier excavations at this site during the 1920’s and early 1930’s revealed abundant evidence for water laid deposits at several distinct levels in the ruins. Furthermore, it was hoped that new information could be obtained concerning the latest occupations of the city and the period of declining prosperity leading to the final abandonment of this once prosperous metropolis.

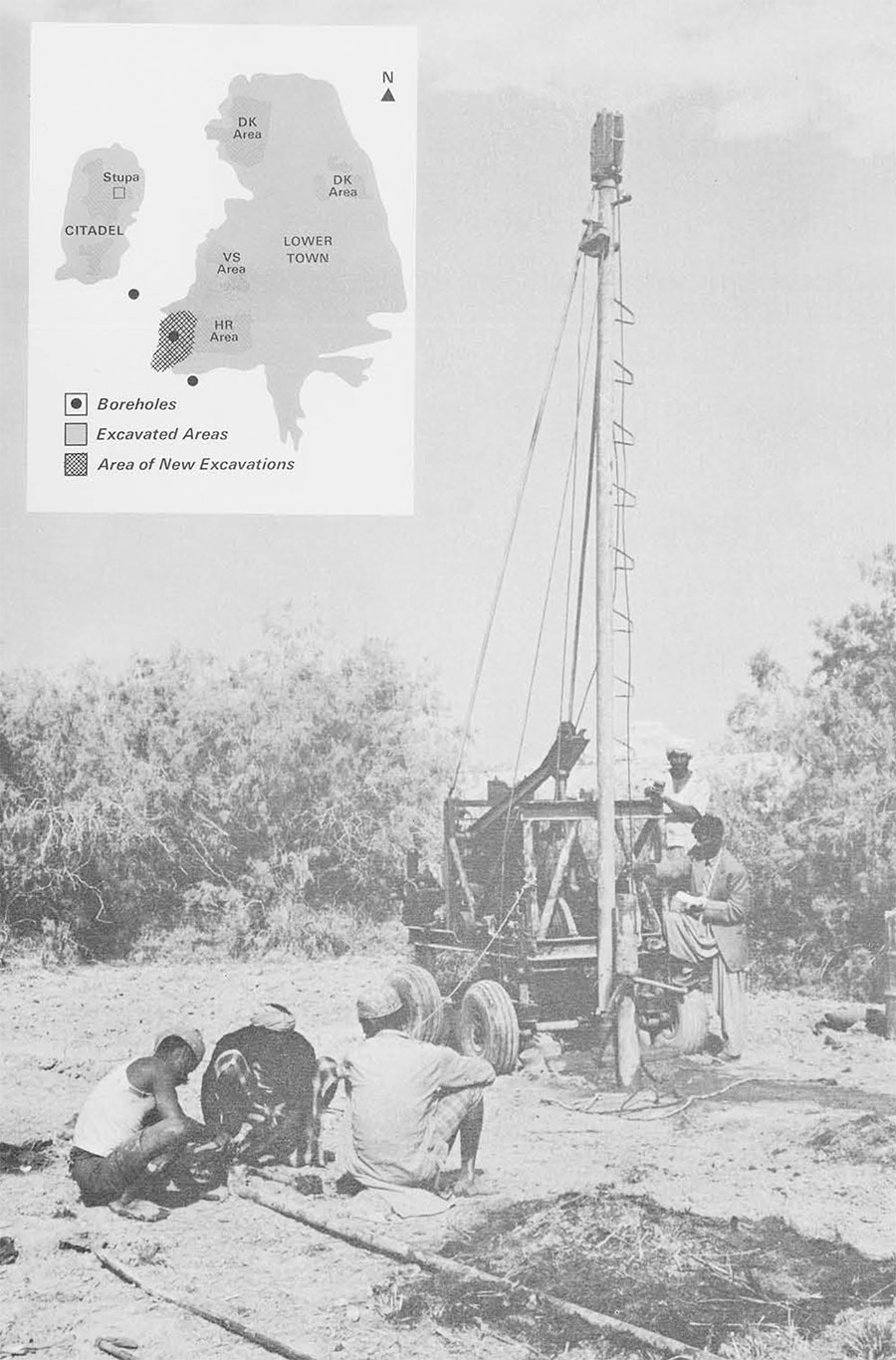

One of the first objectives of this year’s work was to determine the depth of occupation at Mohenjo-daro. The earliest levels have never been reached because of the present high levels of the sub-surface ground water. It is important for our studies into the history of flooding in the lower Indus Valley that we have a complete stratigraphic picture of the successive occupation levels of the city. A boring rig was obtained from a Pakistani engineering company and a series of test bores was made under the supervision of Mr. Raikes. Core samples were brought up and examined every foot or so. Pottery sherds, brick fragments, bangles and ash were found down to a maximum depth of thirty-nine feet below the present plain level. The borings were continued down some eight feet below the lowest trace of human occupation. The present ground water level is about fifteen feet below plain level. Thus it will be necessary to penetrate over twenty-five feet through water soaked levels to reach the earliest occupation. Raikes, in consulation with engineers in Pakistan, is designing a de-watering system for this purpose.

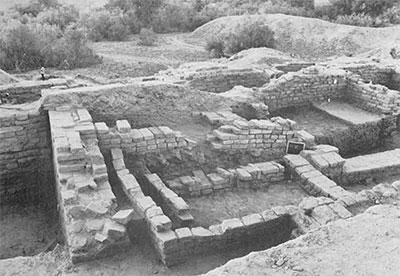

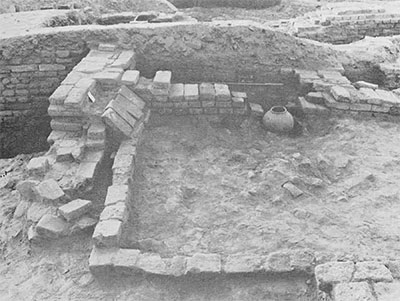

The excavations of the uppermost levels were conducted in a twenty-meter square area on top of the HR mound. Even this relatively limited exposure provided some new and interesting information on the latest period of occupation, an occupation which probably characterizes the general conditions which prevailed at the end of the Harappan period. Immediately below the surface of the mound we found at thin, poorly preserved level which suggests a squatter-type occupation. The buildings were crudely constructed of secondhand, often broken, bricks. The earlier excavators at Mohenjo-daro have reported similar remains from other areas of the site. No trace of foreign objects which could indicate the arrival of invaders of non-Harappan peoples was found. The few examples of pottery found in place on the house floors are of standard Harappan types. Noticeable, however, was the complete absence of the black-and-red painted pottery which so characterizes the mature Harappan period. Architecturally it is important to note that before the building of this latest squatter-level the abandoned rooms and alley-ways of the previous occupation were completely filled in with rubble and grey dirt. Also, crudely made packing walls were constructed to face portions of these fillings. When such fillings were removed during our excavation it was found that these structures so filled in were still in fairly good condition and should have been adequate for habitation. Why then did the last occupant of the city go to the trouble of packing these areas with from three to four feet of fill? If the overall picture we are obtaining from our other studies is correct, it becomes obvious why this elaborate filling and platform making was undertaken. It was the last of several attempts on the part of the Mohenjo-daro population to artificially raise the level of the city to keep above the height of the flood waters. The flood evidence will be described below. I mention it here merely to emphasize our impression that flooding was the principal enemy of the Mohenjo-darians, and of all the Harappan period inhabitants of the lower Indus Valley. Bands of raiders from the nearby Baluchistan hills could well have taken advantage of the chaotic conditions following the floods, but they were apparently not the cause of such conditions.

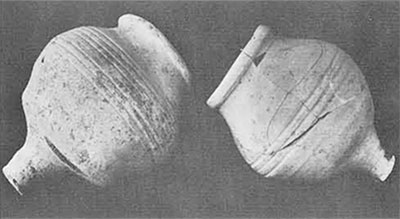

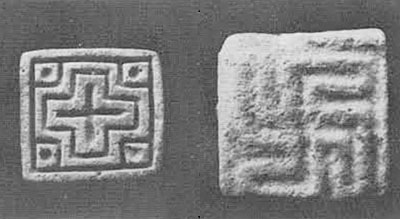

I mentioned that directly beneath this shoddily built squatter level there are the remains of substantial buildings of baked brick with the paved washing (or toilet) areas and the elaborate drainage facilities typical of this civilization. Three to four closely interlocked building and rebuilding levels were uncovered this season. These levels belong to what has been called in the earlier excavation reports the Late period of the city. It has always been difficult when using these reports to define exactly what characterizes the Late period from the Intermediate and earlier periods of the city and the civilization it represents. Certain details relative to the decline in material prosperity of the population of these late levels were noticeable, however, in the new excavations. Pottery, for example, was of typical Harappan shapes but the proportion of painted to plain wares was very low. The luxury of decorating pottery with elaborately painted designs was apparently beyond the means of the late inhabitants of the city. One type of pottery vessel, usually called the Indus Valley goblet, was found in great abundance in these late levels. This confirms the earlier reports and those from other sites which maintain that this distinctive vessel was used only during the late declining years of the civilization. Other evidences of stylistic change and preferences attributable to the Late period were also found with other classes of objects. Stone stamp seals with exquisite animal representations executed in intaglio are one of the hallmarks of the mature Harappan civilization. Several of these seals were found in our late levels but it is fair to assume that such beautiful–and no doubt expensive–objects were kept by families and individuals long after the time when they were manufactured. Another type of stamp seal, cheaply made of paste or frit, with only geometric designs, appears to be common only to the later period of the city. A few scattered examples have been previously recorded (with reservations by the excavators) from Intermediate levels at Mohenjo-daro but they are rare indeed. The geometric seals would then appear to be a potentially useful dating object. Clay animal figurines provide another relative dating criterion. The figurines of the mature Harappan period–mostly of bulls–are superb examples of ceramic artistry. The sensuously modeled bodies, the sensitive faces, and the attention to detail place the best examples of these figurines in a class of artistic excellence with the intaglio representations of animals on the stone stamp seals. In our Late period levels on the top of HR mound not a single example of these excellent animal figurines was found. Figurines were abundant but they were of a crude, almost toy-like quality. The bodies are poorly proportioned and the faces range in appearance from the comic to the grotesque. From the published reports on the earlier excavations at Mohenjo-daro and other Harappan sites it is clear that such figurines are found throughout all levels of the civilization. Our excavations this year seem to show, however, that this is the only style of animal figurine made during the declining years of the civilization. Examples such as those just cited can be helpful for relative dating purposes but cannot tell us anything about the actual year-dates of the city or the civilization. For this purpose carbon samples of wood and grain were collected and will be tested by the radiocarbon dating procedure.

One of the most unexpected finds of the season came on the second day of excavations. Only about two feet below the surface of the mound was found a group of three human skeletons–a middle-aged man, a young woman, and a small child. A few feet away, in the same stratum, were later found two more adult skeletons. These were obviously not burials in the formal sense of the word. The skeletons were enmeshed in a thick accumulation of bricks, broken pottery and debris and were definitely not resting on a street or floor level. This accumulation did not apparently belong to the time of the structural remains in close proximity to the skeletons. What actually happened to these unfortunate persons must remain an enigma. All we can safely say is that their skeletons were found in an archaeological context which must be dated to some undetermined time after the so-called Late period at Mohenjo-daro. They may belong to the time of the latest squatter settlement but too little of this uppermost level was preserved to allow dogmatic claims for dating. It is reasonable to believe that the thirty-seven or so skeletons found in the earlier excavations were also found under similar circumstances. Certainly no fuel has been added by the new discoveries to the fires of they hypothetical destruction of the city by invaders.

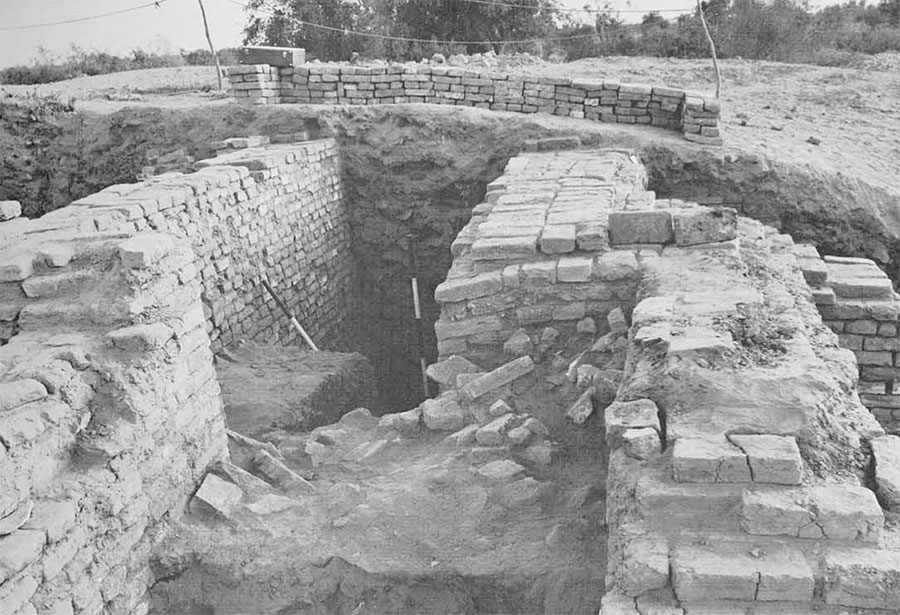

It must be admitted that further excavations at Mohenjo-daro, or any other Harappan period site, stand little chance of answering the vital question of why and how this most extensive of the earliest Old World civilizations vanished from the historical scene. Different types of research, such as the geomorphological studies of Mr. Raikes, may hold the key to this vexing problem. His attention was first drawn to this problem by published descriptions of thick deposits of alluvial clay at various levels in the ruins of Mohenjo-daro. The highest of these “perched” strata of flood deposit is now some thirty feet above the plain level. Up until now there has been no satisfactory explanation for the presence of such deposits. Raikes recorded some 150 exposed clay deposits at widely separated locations in the Mohenjo-daro ruins. Some of these proved to be decayed mud-brick fillings and platforms rather than flood deposits. They are, nonetheless, important because we can now see that the construction of such high platforms at this and other sites was closely connected with the whole problem of flooding. Mention has already been made of the artificial packing and platform building in the latest levels at Mohenjo-daro. Overwhelming evidence for such building practices was uncovered in our clearing of the western edge of the HR mound.

A monumental solid mud-brick platform, or embankment, lines the edge of the city mound. An exploratory excavation showed that it is at least twenty-five feet in height. At present plain level it is faced with a solid fired brick wall, five to six feet thick, which was traced for a distance of over three hundred meters along the base of the mound. This enormous complex, especially if it surrounds the entire lower town area of Mohenjo-daro, cannot be explained merely as a defensive structure against military attack. It appears that the walls and platforms were intended to artificially raise the level of the city as protection against floods. It is still too early to outline in detail the sequence of natural events which could have produced the flooding around Mohenjo-daro but some tentative suggestions should be made. “That the prime cause of the floodings was of a tectonic nature cannot, on present evidence, be reasonably doubted,” says Raikes in his Interim Report. These uplifts, or rather series of uplifts, occurred between Mohenjo-daro and the Arabian Sea, possibly near the modern town of Sehwan. Whether these uplifts were the result of bedrock faulting or of eruptive extrusions of “volcanic” mud remains to be seen. Geologists agree, nonetheless, that the uplifting did occur. The “dam” created by this uplift process backed up the waters of the Indus River. The degree of evaporation, sedimentation, and water losses through the “dam” itself are technical matters requiring much more study. These factors are important in estimating the rate of water rise and spread in the reservoir created behind the “dam.” What is apparent even now, however, is that–again in Raikes’s words–“flooding would have been by gradual encroachment from downstream with plenty of warning.” As the Mohenjo-darians saw the waters gradually approaching from the south they would have had ample time to construct the massive brick platforms such as exist throughout the city. Eventually the reservoir, which could well have been over a hundred miles long, engulfing all the towns and villages in the lower Indus Valley, would have become silted. The inflow of water would have exceeded the losses resulting from seepage and evaporation, and the rising waters would have overtopped the “dam.” A period of rapid water loss and down-cutting of the sedimentation in the valley would follow.

It can be only a guess but it has been estimated that the time required to silt up the reservoir could possibly be as little as one hundred years. During this period, places like Mohenjo-daro may have been temporarily abandoned but this has not yet been displayed archaeologically. At any rate, once the waters began to subside, rebuilding was undertaken. Unfortunately the uplifting-flooding cycle repeated its destructive course, possibly as many as six times. As Sir Mortimer Wheeler, who excavated at Mohenjo-daro in 1950, has recently put it, the population was being worn out by the natural environment (opposite to his original suggestion that the population was wearing out the landscape). A study of silt deposits at other sites near Mohenjo-daro, such as Jhukar and Lohumjo-daro, suggests the same flooding regime. It is essential that detailed surveys and test trenchings of other sites in the lower Indus Valley be made. If consistent patterns of siltation and rebuildings can be worked out for other sites in this area, we will have gone a long way toward substaining the crucial role of tectonic movement and flooding in the life and death of at least the southern part of the Harappan “empire.”

Other factors were involved in the decline of the Harappan fortunes in the north. Flooding may have been a problem there too but not to the overwhelming degree it was in the south. Unfortunately, the archaeological evidence for the end of the northern cities is even more laconic than that for the south. There is an apparently consistent pattern, however, that is common to each of the few Harappan settlements which has been excavated in the north. There seems to be a sharp termination of occupation at these sites during what is recognized on present evidence as the mature phase of the Harappan civilization. Then there was a long period of abandonment followed after several centuries by the settlement of entirely new cultural groups. Most common seem to be the makers of a distinctive painted grey-ware pottery.

The southern regions would seem to hold out the best promise of archaeological answers to the question of what happened to the Indus population after their civilization was defeated by the relentlessly re-occurring floods. Over eighty Harappan period sites have been located by Indian archaeologists in the Gujarat area of western India. Many of these sites are of the Late period and clearly preserve evidence suggesting a gradual transition of the once proud Harappan traditions into those which were indigenous to that part of India. The strength and vitality of the Harappan culture was vanishing ot the point where even the use of writing lost its importance. It is perhaps hopeful to reflect on the possibility that at least in the days of four thousand years ago man’s most overwhelming and stifling enemy was to be found in the forces of nature rather than in the vagaries of his fellow man.