From Chas, Warren, Underground Jerusalem, 1872.

The University Museum takes pleasure in congratulating the Palestine Exploration Fund on its centenary and in recording its appreciation of the always friendly relations which have existed between the two institutions. The Museum’s first expedition to Palestine was in 1921 when the excavation of Beth Shan was begun. Work continued there for eight seasons, the last in 1933, the current reports appearing regularly in the Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement. Since 1956, the Museum has had expeditions at el-Jib and Tell es Sa’idiyeh and has always found the Palestine Exploration Fund a good neighbor.

On Friday, the 12th of May, 1865, in the Jerusalem Chamber of Westminster Abbey, a meeting was called to organize a society to promote the physical exploration of Palestine. For–even though Palestine was the Holy Land, the focus of the great religion which united the countries of the West–exact knowledge of it lagged behind that of Egypt and Assyria. By the mid-19th century, both these biblically peripheral countries were relatively well known to archaeology, while such fundamental questions as the exact location of Solomon’s temple and just what, if any, historical site was marked by the Church of the Holy Sepulchre went unanswered.

But if the problem was immense, so was interest in the solution. The Palestine Exploration Fund, this year celebrating its centenary, was born of that meeting at Westminster Abbey. The list of original subscribers is, in effect, a page from a Who’s Who of the 1860’s. One Charles Darwin, Esq., F.R.S., pledged eight guineas (to be paid over a period of three years) and his friend Joseph Hooker, also a member of the Royal Society, gave a similar sum. Austin Layard, retired from Assyrian exploration and now an MP, pledged ten pounds and the Rev. Professor Rawlinson (brother of Sir Henry, the cuneiformist, and author of a number of books on the Ancient East), two. Subscriptions from John Ruskin and Giles Gilbert Scott, R.A., showed the interest of artists and architects. As one would expect, many church dignitaries and members of the peerage made pledges. But the long list of well-known publishers contributing is something of a surprise: John Murray, George Eyre, E. Spottiswoode, A. Macmillan, Messrs. Longman, Robert Chambers, Herbert Duckworth, and the Rev. Jonathan Cape. Their contributions ranged from two to twenty-five pounds. With so distinguished a parentage, a distinguished program was naturally projected. Investigation was to be carried on in a purely scientific and non-controversial manner in five fields: archaeology, anthropology, topographical survey, geology, and botany and zoology. Please note, this was a century ago, yet nothing was said about the specific elucidation of the Bible. It was a tremendous program; one that men could draw up in the comfort of London to be conducted in the disease-ridden heat of the Holy Land.

Since the Palestine Exploration Fund celebrates its centenary this year, one naturally asks how well this program has been carried out and how closely the original program has been adhered to. These questions can best be answered by the narrative of its works. Though the temptation to begin excavation at once was great, the Fund, with the exception of Warren’s soundings at Jerusalem, very commendable began on the more fundamental survey aspects of its program. Large volumes on the flora, fauna, and geology of the Holy Land appeared with commendable promptness; however, the great topographical surveys is certainly one of the main contributions to human knowledge made by the PEF. Many maps had already been made by travelers, antiquaries, even Napoleon I, but few attempted to plot any but the best-known holy sites. The PEF Survey of Western Palestine, published at a scale of eight miles to three inches, not only showed accurately all hills and valleys, cities and rivers, but located som 10,000 place names with precision, as it is very often the modern name which gives the clue to a biblical site. Drawings of many antiquities and plans of ancient ruins were given in the seven volumes of Memoirs which accompanied the survey sheets. Maps of Sinai and as much of eastern Palestine as Bedouin hostility permitted were also published.

The Fund was fortunate in obtaining the services of the Royal Engineers to do the actual surveying; the party at various times being commanded by Capt. C.W. Wilson (later Col. Sir Charles); Capt. C. Warren (later General Sir Charles); Lt. C.R. Conder (later Col.); and Lt. H.H. Kitchener (later General Lord Kitchener of Khartoum). Photographs of many holy sites were taken and sold to subscribers one compendium entitled “Lt. Kitchener’s Guinea Book of Photographs of Biblical Sites” remains the only book ever published by the distinguished World War I general.

From C.R. Conder, Heth and Moab, London, 1865.

Vivid progress reports of the Survey work were features in the early issues of the Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement, a learned journal celebrating its centenary in 1969, which has become known as the PEFQS. In its pages we find Capt. Warren and the loyal Sgt. Birtles floating on a discarded door through the sewage of Jerusalem in an effort to trace an underground passage; Cpl. Philipps, unable to snap views of Herod’s Dead Sea fortress of Masada when the emulsion ran from his photographic plates in the high temperature of the Jordan Valley; fur flying amongst the survey members as to the exact interpretation of the little mounds studding the countryside which we now know to be accumulations of ancient cities, or “tells”; difficulties when the locals who feared the survey party might be Turkish tax collectors disguised as Royal Engineers declined under any circumstances to identify a locality.

One cannot but wonder at the industry of these Victorians. Clad, doubtless, in uniform appropriate to an English summer, they simply ignored the heat. Nor did they have any idea of the eight-hour day. Successive commanding lieutenants apologize for being too tired to work over their notes later than 10:00 P.M. after a day of open-air survey. And when Warren was sent to the Beqa’a to recover from fever, the idleness so smote his conscience that he made plans of a dozen or more delightful little Roman temples on the slopes of Mt. Hermon, which have probably altogether disappeared from sight in the years since.

From H.H. Kitchener and G. Armstrong, Thirty Years’ Work in the Holy Land, Palestine Exploration Fund, London, 1895.

As miscellaneous discoveries were made, whether or not by the Fund, they came to the attention of its agents and were duly reported through the PEFQS. In 1869, a German missionary discovered the Moabite Stone, recounting hostilities between Omri of Israel and Mesha of Moab from the viewpoint of the latter. In 1874, one of the Greek inscriptions forbidding Gentiles to enter the temple, word for word as described by Josephus, was found. In 1880, the rock-cut inscription in the Tunnel of Siloam, almost certainly recording anti-Assyrian defence measures of Hezekiah of Judah were discovered. It began to look as if Palestine would yield up inscribed documents on the scale of Egypt and Assyria. But this proved to be a false promise and little further epigraphic material came to light in the ’80’s…or at any time since.

From Flinders Petrie, Tell el Hesi, London, 1895.

In 1890, the survey completed and published, the Fund began on its serious excavation program, hiring the Egyptologist Flinders Petrie, to dig at Tell el-Hesy, then thought to be ancient Lachish. Petrie’s six weeks’ work at Tell el-Hesy resulted in his demonstration of stratification and the observation that different types of pottery marked the differing strate. Petrie was able to correlate the pottery with dated wares from Egyptian tombs, thereby providing the backbone for the rough ceramic dating scheme which has ever since been in use in Palestine in lieu of more exact epigraphic information.

As Petrie wished to spend no more than one season away from Egypt, the work at Tell el-Hesy was taken over by Frederick Jones Bliss, son of Daniel Bliss, who had founded the American University at Beirut. The younger Bliss continued with the Society for a decade; his knowledge of Levantine people and manners was especially fortunate, and such contributions as his articles on the Maronites and other sects in the PEFQS are still standard bibliography for the subject. Bliss also made excavations at Jerusalem and on a number of smaller sites for the Society. The big excavation of the early 20th century was that of Gezer, directed by R.A.S. Macalister. His three-volume report is perhaps to be especially distinguished as written to show what the discoveries meant in terms of a way of life, rather than simply a record of objects found.

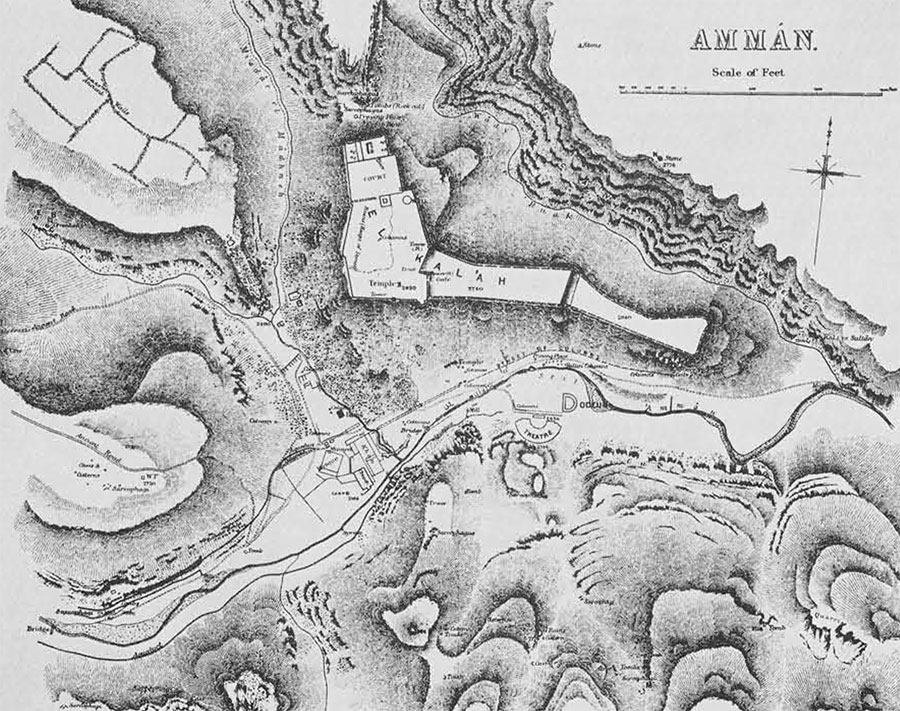

From C.R. Conder, Survey of Eastern Palestine, London, 1889.

After the dislocations of the first World War, both rising costs and the fact that the PEF was no longer alone in the field resulted in the initiation of the present practice of cooperative digs. The first of these, at Israelite Samaria, contributed much to the accurate definition of the various pottery complexes in use during the latter part of the Iron Age. Also, by this time, Near Eastern archaeology was slowly changing its focus; where the biblical and earlier historical periods had previously been its main interest, this now shifted to the prehistoric period, as the results of nearly a century’s work showed that the fundamental techniques of civilization–agriculture and husbandry–must have originated somewhere in the Anatolia-Palestine-Iran area. In the ’30’s a PEF-American School of Prehistoric Archaeology joint expedition at Mt. Carmel, directed by Dorothy Garrod, uncovered both Palaeolithic man and his agricultural, or near-agricultural successors. A simultaneous excavation at Jericho by John Garstang made it clear that these very early cultures were present at the base of the Jericho tell. Jericho was later excavated in greater detail by Kathleen Kenyon for the PEF and other groups in the 1950’s. Here forty-five feet of accumulation before the invention of pottery was discovered, including two Stone Age cities dead and gone three thousand years before the first pyramid was built.

The century’s advances in archaeological technique are today being applied to that most difficult of all sites, Jerusalem, on another excavation directed by Miss Kenyon. Still in progress, the current Jerusalem excavations have perhaps discovered the meaning of David’s Millo, found traces of that monarch’s quarters, outlined Nehemiah’s Jerusalem, and shown that the site of the Holy Sepulchre is beyond the second city wall and on that basis may mark the true site of Christ’s burial.