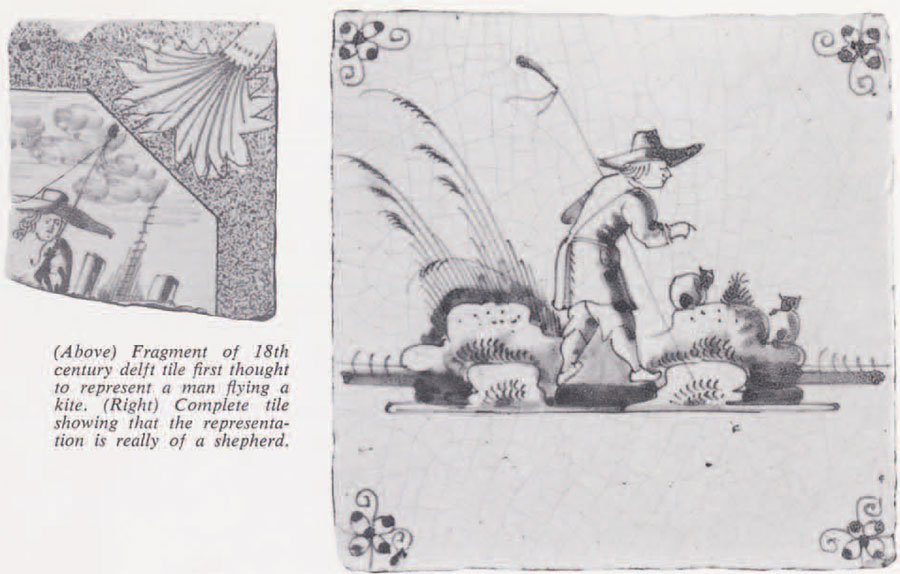

Every now and then a sudden gleam comes to an archaeologist’s eye as he searches a palaeolithic cave deposit, or even an 18th century house foundation. Fancy finding what might be a tangible association of Benjamin Franklin’s famous kite experiment right in the ruins of his own house in Franklin Court, down on Orianna Street, within an echo of Independence Hall!

Well, with a financial assist from the American Philosophical Society, National Park Service diggers in June of 1953 found a fragment of a Dutch delft tile below the modern sidewalk and tiny vacant lot where Franklin’s house once stood. Before leaving for Paris in 1764 to represent the colony, the energetic statesman had directed that the house he had so carefully planned should be built here under the uneasy attention of his wife. With considerable difficulty, described by the harassed Mrs. Franklin in painfully composed letters to her husband, the house was completed next year in the green and open center of the block of town buildings bounded by Second and Third, Chestnut and Market Streets. As for the tile, it was probably in a fireplace of the house, perhaps in the later addition which housed Franklin’s celebrated library.

What excited our interest in the tile is the figure of a man with an object extending far above his head and apparently attached to a line which he holds. A kite?

What excited our interest in the tile is the figure of a man with an object extending far above his head and apparently attached to a line which he holds. A kite?

The Dutch were fond of showing in frugal but expressive brush strokes–learned from Chinese porcelain painters–their everyday doings on such square fireplace tiles. Some show men-at-arms or men working at their crafts; others picture children playing ball, wrestling, running–even flying kites. The last would be a natural selection for Mr. Franklin.

Alas for conjecture! A dutiful and scholarly inquiry was directed by the present Independence Park archaeologist, B. Bruce Powell, to an expert in Dutch tiles, George B. Jackson of Edwin Jackson Fireplaces, New York. Jackson instantly responded with a photograph of a strangely similar figure on a complete 18th century Dutch tile. The “kite” is clearly a shepherd’s staff, reaching to the ground from over the shepherd’s left shoulder!

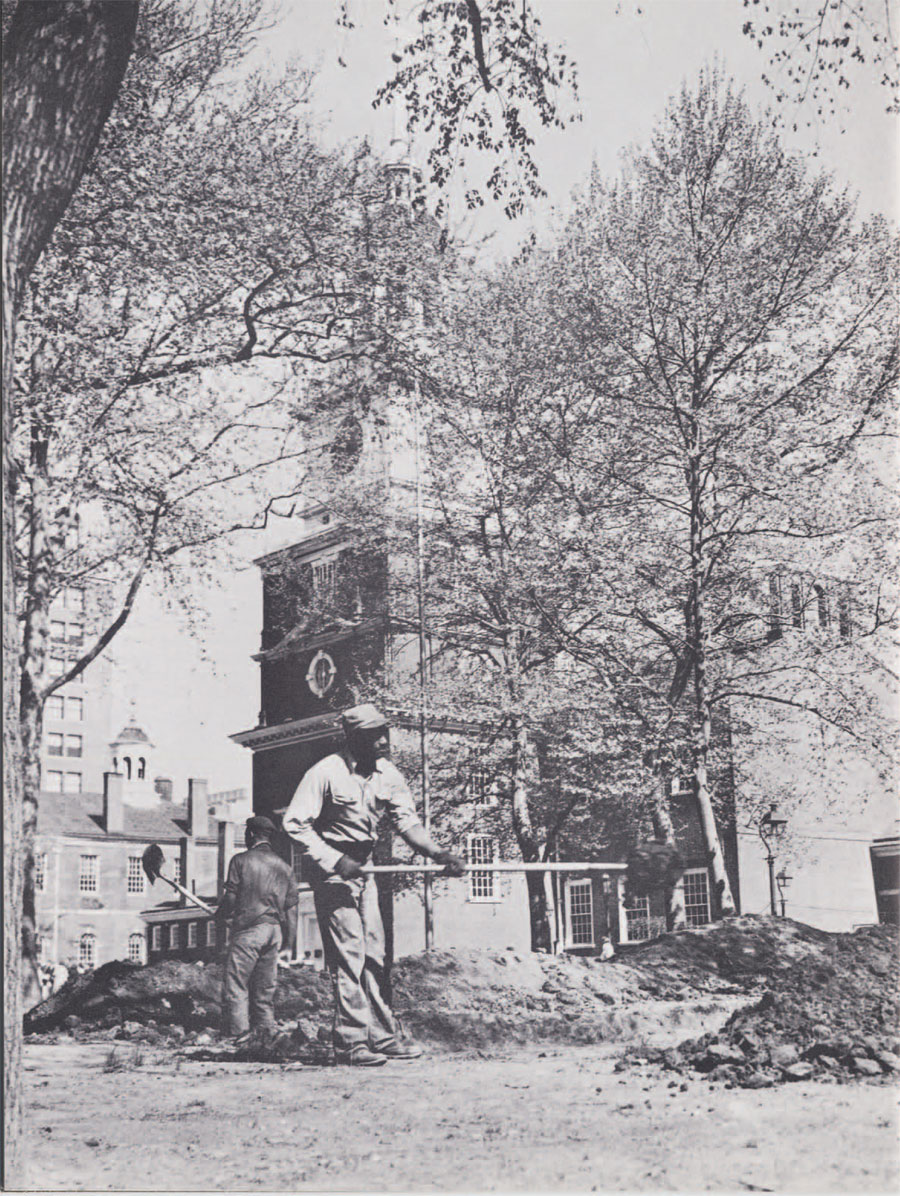

Not much ground in the vicinity of Franklin’s house has remained undisturbed by later buildings, but now that the ground has been cleared and Orianna Street can be blocked off, the area will be completely explored with the hope that a chance pocket of preserved refuse may yield at least one object indisputable connected with that most ingenious of Philadelphians.

The Franklin House is only a portion of Independence National Historical Park. The Park’s five blocks in the heart of Philadelphia comprise the greatest concentration of historic sites in the United States. Here Indians camped before the white man’s arrival, here they parleyed with the early 18th century government of Pennsylvania. Here the Declaration of Independence was signed.

And what has happened to the original scene after nearly two centuries of “improvement,” decay, encroachment, “restoration,” and the present energetic renaissance? Buildings erected as town houses were made over into stores, the re-made again. Office buildings of the later 19th century surmounted and largely obliterated all traces beneath them. Now all have been leveled to allow breathing space for the little nucleus of the shrine of liberty. Not much actually remains beneath the ground: some badly interrupted foundations, a few wells, cisterns, and privies, a quantity of refuse–and many questions.

The challenge to the archaeologist here, as in all historic urban renewal areas, has been to work within the narrow confines of research possibility, so pacing and limiting his activities that he does not delay demolition or construction. He often works just before and just after the event of destruction and in and around disruptive intrusions. Quantitatively the results are not very impressive. No historically vital questions have been answered, no decisions made which will change the outlines in history texts.

What then can archaeological investigation accomplish? Sparse as his product may be, the archaeologist has provided something that was not there before: the assurance that no stone, literally, was left unturned to provide the last ounce of physical evidence for the record. And, perhaps more important, the artifacts he has found bring back the literal feel of history.

Since these artifacts are clues to activities and ideas of their time, there must be much preparation and research. At Independence, the historical research which furnished a prologue to digging began in 1951. It continues as the digging goes on. And after the last trowelful has been turned, research will still continue. First there is research into the physical, political, and social history of any structure, feature, or site in the Park, and into all persons and events connected with it. So far, more than two million manuscript and other primary records have been examined. Park historians, working as a team, have accumulated more than 40,000 research cards; 29,000 photographs, photostats, and prints; 55 rolls of microfilm; and a 2,200-volume library. This is a beginning.

Then there is the architectural investigation–the study of building elements and details, the measured drawings–all undertaken while over a million visitors a year must be allowed to walk through these ancient fabrics as freely as possible. Obviously the balance of attrition and preservation is a delicate one.

Actual archaeological excavation began in 1953, and continues. The official premise of the work is the requirement that, in the spirit of the Antiquities Act of 1906 and the Historic Sites Act of 1935, physical development which endangers archaeological values calls for the salvage of these values before the development takes place. The view that the “march of progress” takes precedence over the preservation of these values undisturbed beneath the ground is a pragmatic one which may be questioned several hundred years hence.

In 1953, Paul J.F. Schumacher, the first project archaeologist, graduate in anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania, began systematically testing construction areas. Progressively, post-18th century buildings on historic sites were removed and the ground searched for earlier walls which had not been destroyed by cellar excavations, for wells and privies and artifacts still intact in tiny yards and below sidewalk and street paving. In 1957, Schumacher left to become Regional Archaeologist at San Francisco and B. Bruce Powell, Virginia born archaeologist who trained at the University of Michigan, came from the Jamestown excavation project to continue the Independence dig.

As architectural and ground searches continued, two major sites and many minor ones were developed. The major ones were Independence Square and Benjamin Franklin’s house site, the first now completed and the second to be finished in the summer of 1960. Sites of less importance, but of considerable value in establishing historical data and cultural interpretation, were given as exhaustive investigation as the limitations of space and time would permit. And sometimes the archaeologist merely followed closely the progress of demolition that he might observe and record any features around and beneath exposed foundations.

Thus, work in the basement of the Bishop White house (which has been preserved) on Walnut Street between Third and Fourth and in that of the 1880 building adjoining resulted in discovering the Bishop’s cold cellar, his well, and his privy. Also revealed were valuable details of the original architecture, much of the fabric of which had been considerably altered.

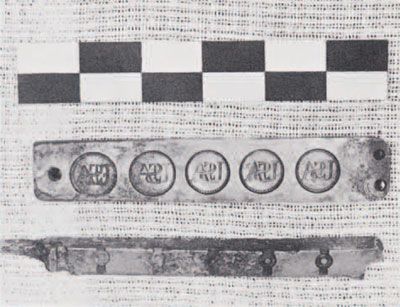

Before the reconstruction, by the National Park Service, of New Hall (originally built by the Carpenters’ Company in 1791) for use as a museum of Marine Corps history, excavations uncovered the original foundation walls of the building and two privy pits, one of which was destroyed by the construction of New Hall itself. A large brick privy pit at the rear of New Hall had been closed with 15 feet of house rubble following demolition activities in the late 19th century. Below, however, in the remaining portion of the pit, to a depth of 22.2 feet, were quantities of artifacts ranging in date from mid-18th to late 19th century. Here is a continuous record of our ancestors’ habit of disposing, as it were privily, of useless or broken objects–even stolen ones–as well as of those accidentally lost.

Sometimes archaeology contributed information available through no other means. Documentary research shows that in 1739 the Province of Pennsylvania had obtained title to a little more than half of the city block now comprising Independence Square. Here the Assembly resolved “…that Materials be prepared for encompassing the Ground with a Wall in the ensuing Spring…” Just where the southern part of this wall was placed has been a question. Records show that the property line ran from Sixth Street 99 feet eastward, made a right angle turn and ran north 80 feet, turned east again for 198 feet, thence south for 80 feet, and, finally, turned and ran 99 feet to Fifth Street. Did the wall follow this line or did it run straight across the Square along the northernmost part of the line? History decided on the latter position. Excavation showed conclusively that neither assumption was correct. The wall ran straight across the Square in line with the southernmost part of the property line, so that some 16,000 square feet of property not even belonging to the Province was enclosed. History, however, records no protest against this primordial government encroachment.

As the shambles of wrecked buildings is succeeded by archaeological trenches and probings, and then by landscaping or rebuilding, another and considerably lovelier aspect grows upon the Independence Park area in old Philadelphia. The spade and trowel have even disclosed the original layout of Independence Square in the late 18th century, when landscapist Samuel Vaughan’s serpentine paths wound gently amid shrubs and trees, within the now-revealed brick wall. This is the scene to be recreated in the Square.

Photographs by National Park Service