“On Monday, the 9th of the Divine month of Azar…[Nov. 20, A.D. 1620], mounting an elephant of the name of Indra, I went towards the city, scattering coins as I proceeded. After three watches and two gharis of day had passed, at the selected auspicious hour, having entered the royal residence, I alighted happily and auspiciously at the building recently brought to completion and finished handsomely by the exertions of Ma’mur Khan [the ‘Lord Architect’]. Without exaggeration, charming residences and soul-stirring sitting places had been erected in great beauty and delicacy, adorned and embellished with paintings by rare artists. Pleasant green gardens with all kinds of flowers and sweet-scented herbs deceived the sight.”

So wrote Jahangir, fifth of the Moghul emperors of India, after his first visit to his newly constructed Quadrangle in the palace-fort at Lahore in 1620. Today, this “Old Fort” comprises the major group of secular buildings in Lahore, among some if the richest and most nearly complete examples of Moghul architecture in Pakistan.

The Moghul empire was founded by Babur (A.D. 1483-1530), a descendant of the Timurids and Jenghis Khan. After successfully invading northern India by way of the Khyber Pass, Babur established his capital at Delhi. Lahore was selected as one of several provincial capitals because of its militarily strategic position and because it was one of the most important commercial and trading centers in northern India.

The earliest history of Lahore itself remains buried beneath the present living city. Archaeogically, its history begins with the fortified palace and city walls of the fourth Moghul emperor, Akbar (A.D. 1556-1605). Akbar’s son, Jahangir (A.D. 1605-1627) was responsible for the building of the magnificent quadrangle that he so vividly describes in his Memoirs. Important additions were made to the fortress complex by Jahangir’s son and successor, Shah Jahan (better known perhaps as the builder of the Taj Mahal at Agra), and by the emperor Aurangzeb in A.D. 1673.

After the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, there followed a long period of neglect and destruction as the Moghul power gradually waned. The splendor of sovereignty was revived for a short time within the ancient walls of Lahore when the powerful young Sikh leader, Ranjit Singh, the “Lion of Lahore,” made it his capital in 1799. His death in 1839 was followed only ten years later by the British annexation of the Punjab. The fort then served as a garrison for British troops until 1923, when it was abandoned.

Moghul architecture, so richly and completely represented in Lahore, displays a curious combination of elements, styles, and craftsmanship. It presents a material manifestation of the religious and cultural tolerance of the early Moghul emperors. By the time of Akbar, the wedding of Islamic architecture familiar to the Moghuls with Hindu architecture and iconography was complete. The profusely sculptured red sandstone buildings of Akbar and Jahangir are distinguished by features of Hindu architecture that would have been more appropriate in wood. Such Hindu decorative elements as animal and human forms that were normally forbidden in the Islamic repertory were carved into the stone.

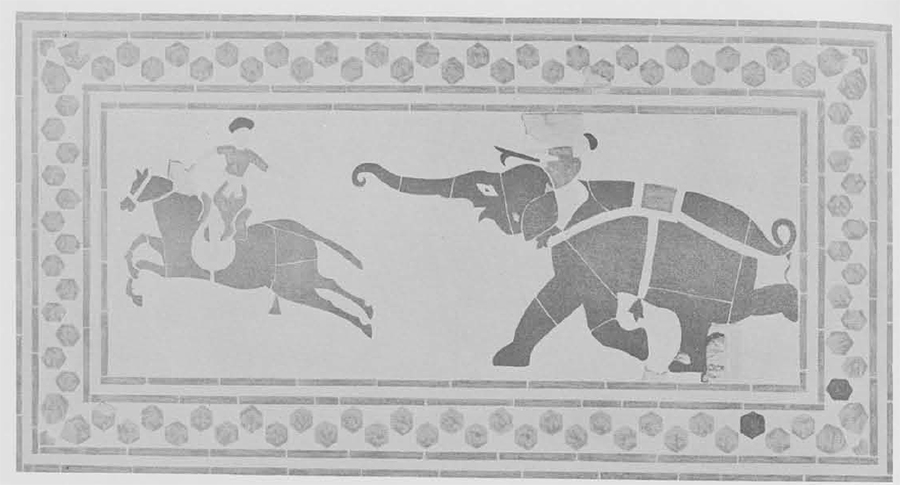

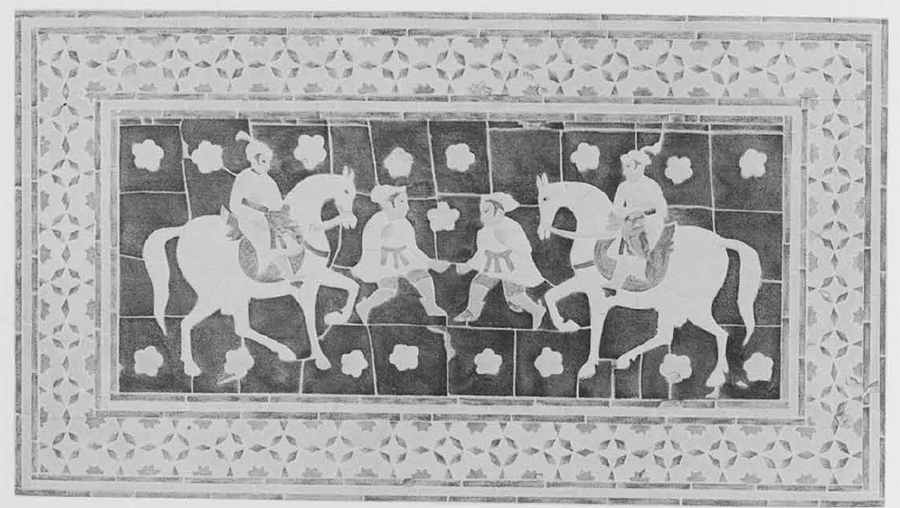

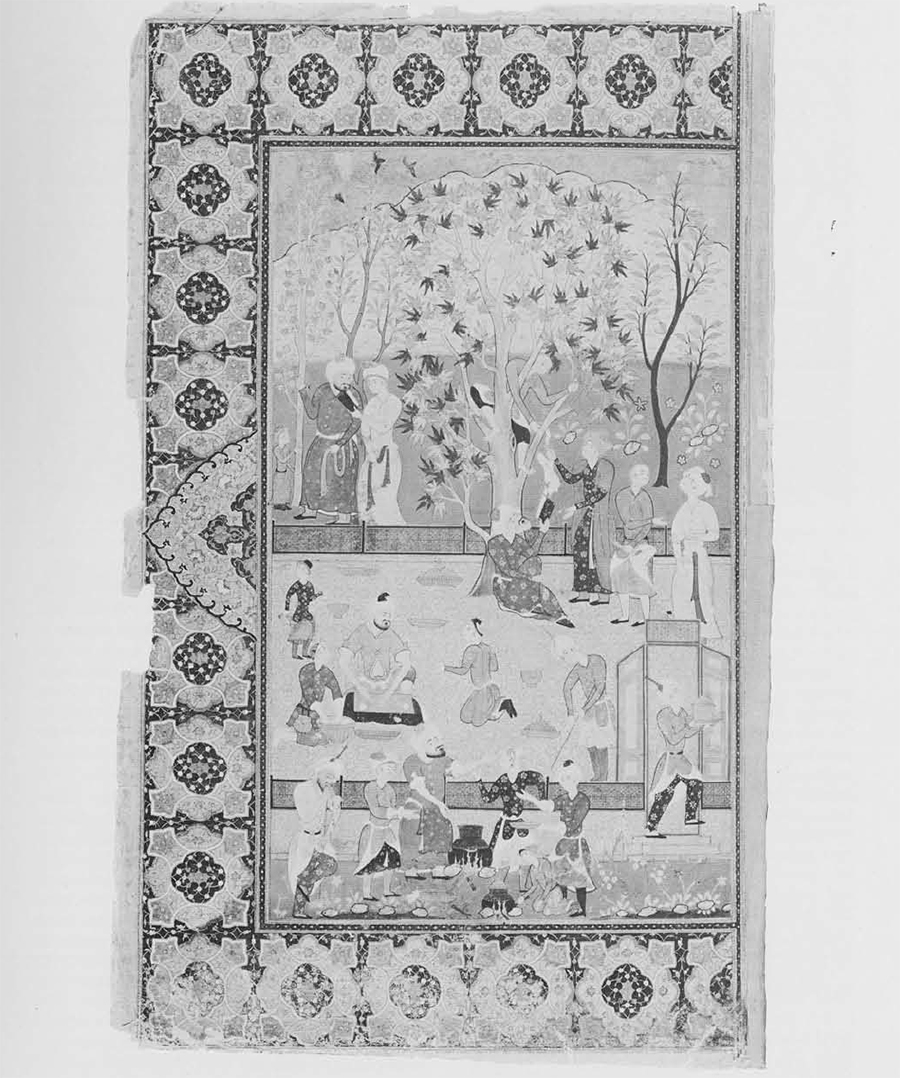

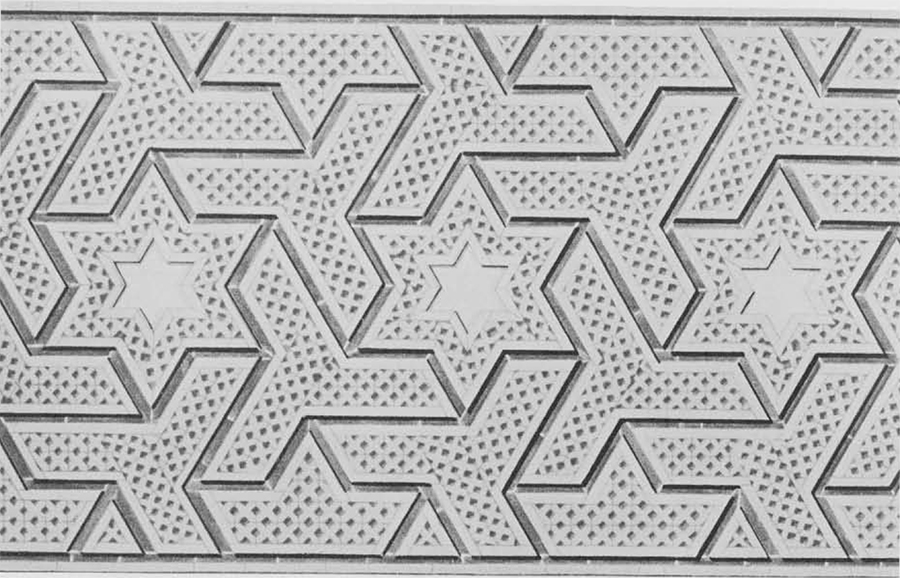

Especially interesting are the shape and position of the brackets under the eaves, the inclined struts supporting the roof beams, and the pillars which are all of stone but obviously derived from wooden prototypes. Shah Jahan’s architects introduced the use of white marble inlaid with floral designs of agate, carnelian, and lapis lazuli. Still another striking feature of the Lahore fortress is the unique decoration of panels of colorful tile mosaics preserved on part of the north and west walls. One hundred and sixteen panels of these mosaic decorations cover a wall five hundred yards long. The manufacturing technique was introduced from Persia but many of the scenes portray Indian motifs. There are scenes of court life, sports, elephant fights, polo games, dragons, and camels as well as the more usual geometric and foliated designs. The identification of the emperor responsible for these magnificent mosaics is uncertain, but the portrayal of living beings–both human and animal–reflects the unorthodox, religiously tolerant tendencies of both Akbar and Jahangir. Jahangir especially had a great fondness for pictures and took pride in his court painters, in defiance of the basic tenets of the Moslem creed.

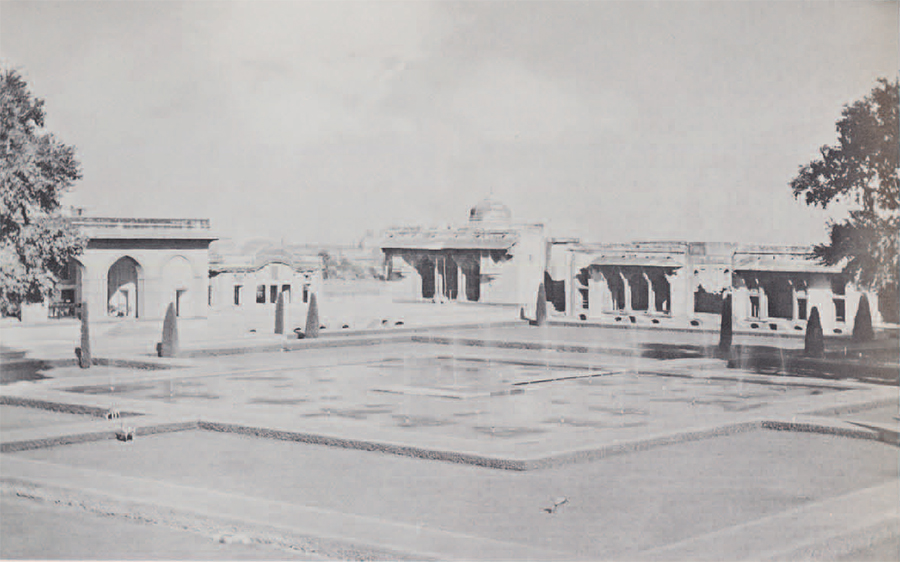

In 1923, with the abandonment of the Fortress by the British garrison, the Archaeological Service of India began the work of restoring, repairing, and preserving what remained of the ancient structures. Since the Partition of Pakistan and India in 1946, the Pakistan Department of Archaeology has continued the work on the Lahore Fort. Lost wall foundations are being recovered, fountains and waterways are being restored, plastered wall surfaces are being removed to reveal the underlying frescoes, damaged sections of filigree stone work and tiling are being repaired.

The Fortress thus is being restored to something of its former physical grandeur. In the Quadrangle, the dusty drill field of the British garrison has now been returned to Jahangir’s glistening pool and beautiful gardens; the heavy, regimented steps of army officers and men have been replaced by the light-footed, carefree steps of small deer and colorful birds; the ranks of shining upright rifle barrels have given way to regular rows of fountains, shooting their cool sprays up into the jasmine-scented air. The modern visitor can appreciate Jahangir’s delight upon seeing his newly constructed Quadrangle and can say with him:

“From head to foot how sweet, turn where I please. Soft glances at my heart cry, Take thy ease.”