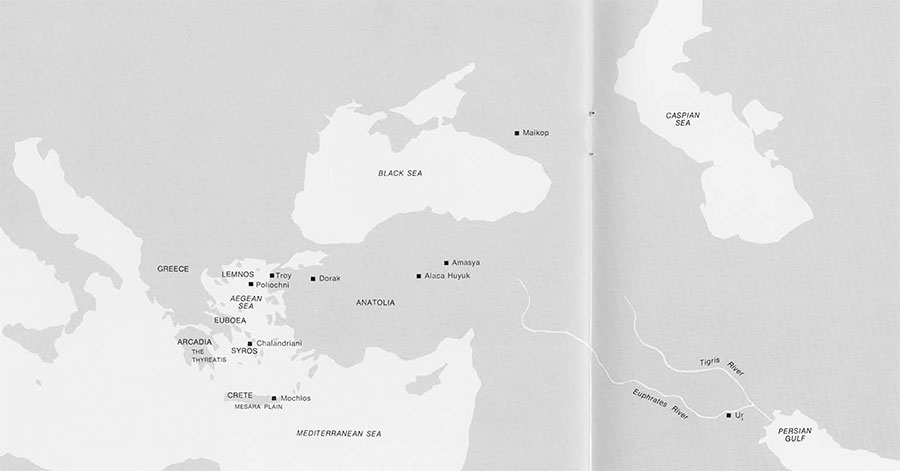

The early Bronze Age in much of the Aegean, Near East, and Eastern Europe might better be called the Early Gold Age, for this is the time of the rich tombs from Maikop in southern Russia, through Alaca Huyuk in central Anatolia and Dorak in western Anatolia, to Ur in southern Mesopotamia, and even over to the tombs of the Mesara plain on Crete. Troy and its neighbor, Poliochni on Lemnos, shared a common source of fine gold jewelry. Traces of the wealth which must have been accumulated by the rulers of such Early Helladic sites as Lerna and Tiryns have not yet been found, but a gold sauceboat from Arcadia and a small hoard of gold jewelry said to be from Thyreatis in the Peloponnese represent metalwork not found again on the Greek mainland until centuries later in the Mycenaean shaft graves. Even a number of gold and silver vessels, now in Athens and New York, are thought to come perhaps from the Greek island of Euboea at about the same time.

The early Bronze Age in much of the Aegean, Near East, and Eastern Europe might better be called the Early Gold Age, for this is the time of the rich tombs from Maikop in southern Russia, through Alaca Huyuk in central Anatolia and Dorak in western Anatolia, to Ur in southern Mesopotamia, and even over to the tombs of the Mesara plain on Crete. Troy and its neighbor, Poliochni on Lemnos, shared a common source of fine gold jewelry. Traces of the wealth which must have been accumulated by the rulers of such Early Helladic sites as Lerna and Tiryns have not yet been found, but a gold sauceboat from Arcadia and a small hoard of gold jewelry said to be from Thyreatis in the Peloponnese represent metalwork not found again on the Greek mainland until centuries later in the Mycenaean shaft graves. Even a number of gold and silver vessels, now in Athens and New York, are thought to come perhaps from the Greek island of Euboea at about the same time.

In most of these areas the following period was poor in comparison, both in precious metals and in fine metal craftsmanship, and it can hardly be coincidental that so much wealth was amassed in far-flung regions at approximately the same time. The socio-economic conditions which permitted the treasures are not fully understood, but surely they allowed trade between some of the centers. Such contacts are important in the study of man for, as M.E.L. Mallowan has said, “the movement of goods must imply the transit of ideas; it is a function of archaeology to elicit the evidence and to draw the proper conclusions from it.”

Unfortunately, direct contacts between Early Bronze Age jewelers have not been easy to trace. Pins with double-spiral heads, and quadruple spiral beads have been found in some of the treasures, but each type has such a wide chronological and geographical spread as to allow only tentative evidence of correlations. Further, the simplicity of such ornaments may have permitted them to be independently invented in a number of regions at different times; one of my students points out that as a Girl Scout she made quadruple spiral beads exactly like those from the Near East.

The University Museum can now provide new evidence for contacts between two of the major centers in question.

Of all the treasures from the third millennium B.C.., certainly no others are so well known as those from the burnt level, labeled IIg, at Troy, and from the “Royal Cemetery” or Early Dynastic Ur. Everyone with an interest in archaeology has seen pictures of Heinrich Schliemann’s wife wearing the famous gold diadem from Troy, and Schliemann’s own description of the discovery and excavation of the first Trojan treasure is one of the most exciting and romantic in the history of archaeology:

‘In order to secure the treasure from my workmen and save it for archaeology, it was necessary to lose no time; so, although it was not yet the hour for breakfast, I immediately had paidos [time for rest] called…While the men were eating and resting, I cut out the Treasure with a large knife. This required great exertion and involved great risk, since the wall of fortification, beneath which I had to dig, threatened every moment to fall down upon me. But the sight of so many objects, every one of which is of inestimable value to archaeology, made me reckless, and I never thought of any danger. It would, however, have been impossible for me to have removed the treasure without the help of my dear wife, who stood at my side, ready to pack the things I cut out in her shawl, and to carry them away.’

Visitors to the University Museum’s Mesopotamian Gallery do not have to be reminded of the spectacular finds made by Sir Leonard Woolley at Ur for the University Museum and the British Museum. “The treasures which have been unearthed from the graves during that time have revolutionised our ideas of the early civilisation of the world,” Sir Leonard wrote in his Ur of the Chaldees.

This emphasis on gold and jewelry has led some to believe mistakenly that archaeologists are overly fascinated by their discoveries of royal tombs and ancient riches. Woolley, himself, has said that such dramatic discoveries as his of the “Royal Tombs” at Ur are hard to see in their proper perspective:

‘isolated by their novelty they come out of focus and dazzle us, but later they withdraw and, linking up with other things in the field of ordered vision, become features in the historical background against which, consciously or unconsciously, we play our part.’

But gold has an archaeological value of its own: unaffected by the destructive forces of time, it is often wrought in such fine and intricate patterns as to offer to its discoverers little doubt of its place of manufacture. A single shape or decorative motif may have been invented independently by two craftsmen in separate parts of the world, but hardly a piece of jewelry made up of hundreds of individual units.

The University Museum has recently purchased a small hoard of jewelry said to have come originally from the Troad. The hoard indicates, for the first time, that Troy received part of its jewelry directly from Ur, or from the source of Ur’s jewelry, and that Ur, on the other hand, possibly received jewelry directly from the workshops which supplied Troy and Poliochni with their precious metalwork.

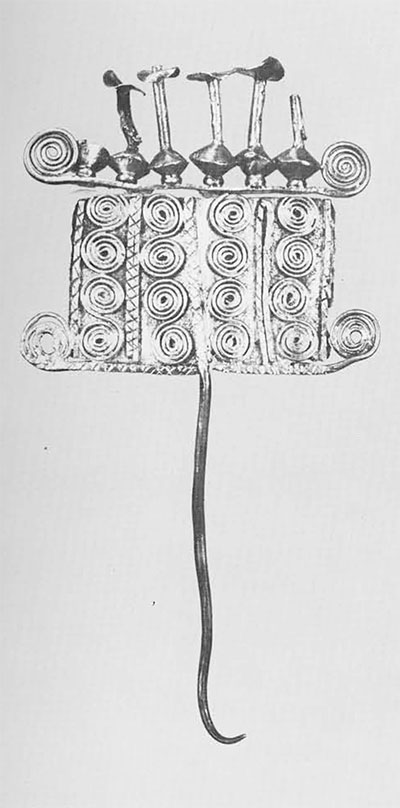

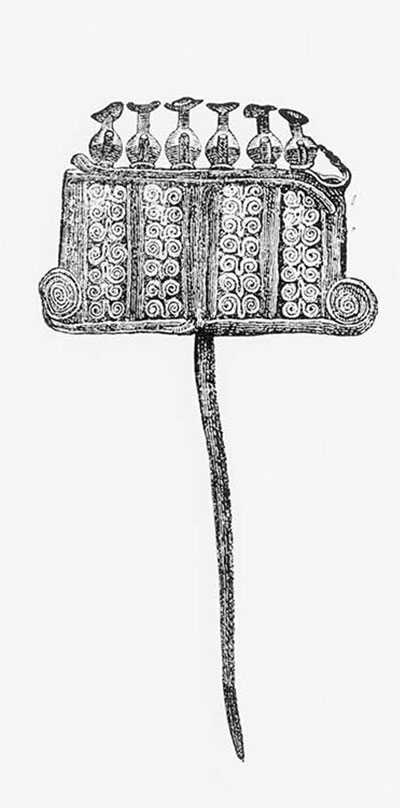

One of the finest pieces in the new collection is an ornamental pin with a large, rectangular plate for its head: the plate, framed between two crosspieces ending in upward-turning spirals, is decorated with filigree S-shaped spirals between cross-hatched vertical strips of metal; six hollow ornaments, in the shape of biconical jugs with pierced discs representing covers atop their tall necks, are attached to the upper crosspiece above the plate. There can be no doubt that this pin is of exactly the same type as an example from Schliemann’s treasures from Troy, and both seem related to a pin from Poliochni with two animals, probably birds, standing on a crosspiece ending in spirals. The use of miniature gold or silver jugs as ornaments is found on simpler pins from Troy, and seems also to have been a decorative feature of the Cyclades (Chalandriani) and the Greek mainland (Thyreatis) at about the same time.

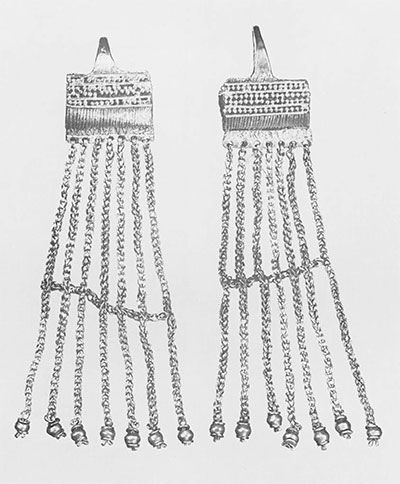

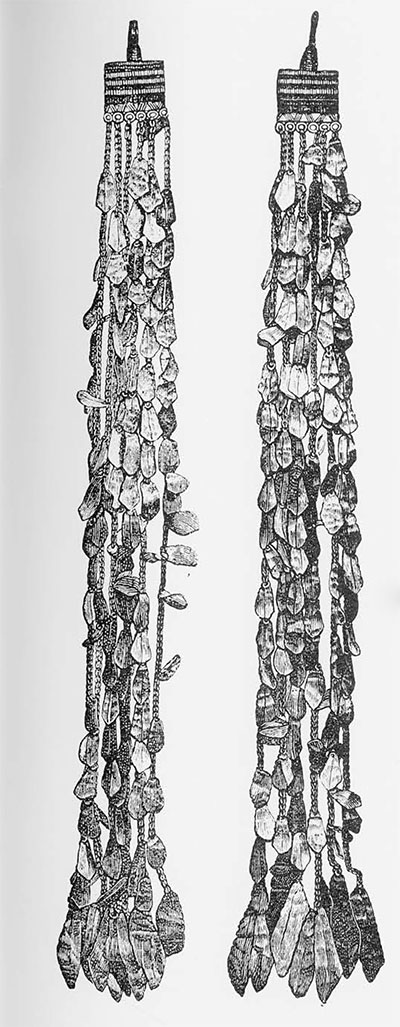

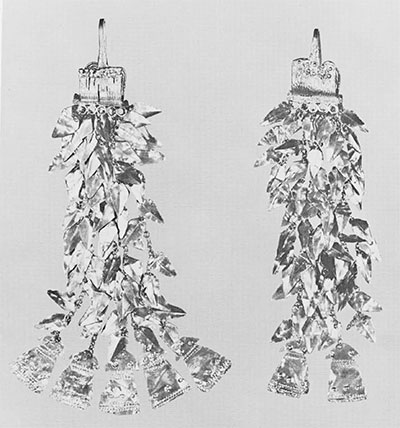

Four earrings are of a type common to both Troy and Poliochni. In these the hooks which pierced the ears were attached to basket-shaped ornaments, usually made of curved wires soldered side by side, from which hung delicate chains variously decorated at their low ends. Two of our earrings seem to form a matching pair. The basket of each is formed of a thin sheet of metal cast with ridges to imitate a layer of wires soldered together on its surface. The tops of the baskets are decorated, just below the clasps, with horizontal rows of granulation much like those used for decoration on similar pieces from Poliochni; the small plates attached to the bottoms of the baskets, each pierced with seven suspension holes and decorated with incised cross-hatching over its top half, are more like plates on earrings found at Troy. The chains themselves are loop-in-loop, as at both Troy and Poliochni, as well as at Ur and on Early Minoan Crete, and are joined together about half way down their lengths by horizontal links of chain, as are the pendant chains of an elaborate gold diadem from Troy. The chains end in small, roundish double-conoid beads with flat, circular spacers above and below; such ball pendants do not seem to be typical of either Troy or Poliochni, but are found on jewelry from an Early Minoan tomb at Mochlos on Crete.

The other two earrings, not quite matching one another, have baskets actually made of separate wires soldered side by side. Each of these has a vertical strip of metal, decorated with incised cross-hatching, centrally dividing the wires. One of the baskets is decorated with a double row of granulation along its upper edge, but the other has instead two horizontal rows of applied rosettes, similar to but not quite duplicated by examples from Troy. Below each basket are two suspension plates, one in front of the other; these are somewhat longer than their baskets and protrude slightly at either end, as on one of the earrings from Poliochni and two from Troy. The frontal plates are not pierced, but have five suspension rings in each case, a device also known from the other two sites in question; our earrings are somewhat closer to the Trojan examples because only there are such rings used, as far as we now know, on the longer suspension plates. Three links of chain ending in a single leaf hang from each of the rings. Longer chains hang from the rear plates, which are pierced with suspension holes in the normal manner. These chains are decorated along their lengths with thin metal leaves and end in flat “idols” cut out of sheet metal and decorated with rows of repousse dots; both the leaves and “idols” are features of earrings at Troy and Poliochni. The University Museum “idols,” of which three are missing from one of the earrings, are all alike and are best matched at Troy; that such “idols” nearly always vary between pieces of jewelry at Troy and Poliochni, however, indicates that goldsmiths did not wish to duplicate their patterns between individual pieces or sets of jewelry.

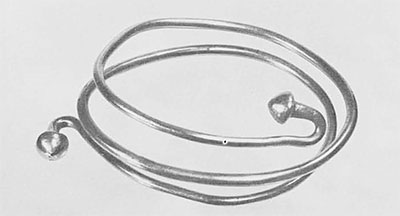

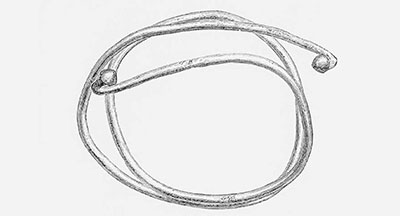

A spiral bracelet made of a heavy round wire with its ends formed into conical knobs and turned back, is perfectly duplicated at both Troy and Poliochni. The specific gravity of this piece, the only one tested so far, indicates that it is not pure gold, but is probably electrum with a rather high silver content. Further analyses will soon be made.

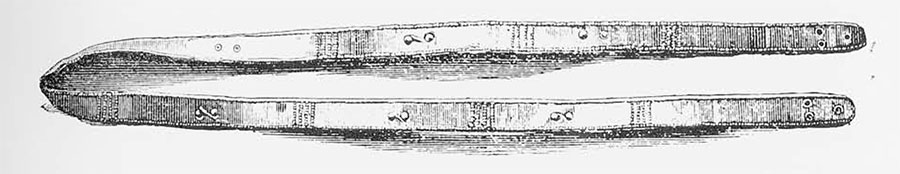

A thin diadem, cut from a sheet of metal, is decorated with a border of repousse dots along its top and bottom edges, and similar dots form a series of diamonds and rows of both vertical and oblique lines between; rosettes made of small circles of dots in the centers of the diamonds, however, were chased, or punched from the front, around their repousse centers. The diadem could easily come from Troy, although its exact pattern is not found there. A similar pattern, but lacking the rosettes, is found on a diadem from Mochlos, probably of the Early Minoan II period; the duplication of such a simple design, however, is not necessarily meaningful in a study of trade and interconnections.

Eleven earrings were cast as solid, ribbed pieces in imitation of separate wires soldered together, and then curled into “shell” shapes. A mold for such earrings, now in the Louvre, is said to be from Anatolia. Eight of ours are plain, as are many at both Troy and Poliochni, but single examples decorated with rows of granulation or a single applique boss are best paralleled at Poliochni; one example, with filigree S-spirals flanking a conical stud, is not duplicated by Trojan examples but is certainly of the Trojan type.

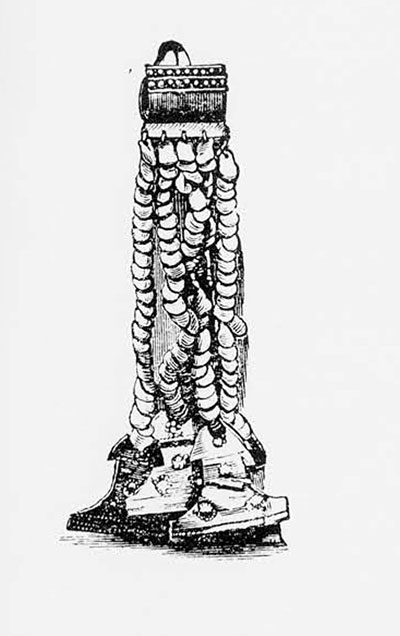

Also in the hoard are 220 beads, including plain rings of various sizes; teardrop-shaped pendants of sheet metal, curled into hooks at their upper ends; rings with their outer faces notched or scored all around; cigar-shaped spacers; spherical beads made up of flat segments; square beads pierced with round holes; and flat separator-beads, pierced with four holed each to keep apart four strands of a necklace.

Five pieces remain to be described, and these are of the greatest interest because of their links with the “Royal Cemetery” at Ur. Four of these are almost identical pendants made of wire hoops encircling, in each case, four cones of coiled wire. The conical spirals of each pendant are made of two wires, coiled at either end, and in three cases twisted together to make a vertical rope pattern between the spirals; the hoops of these same three pendants are of quadruple wires incised all around with a chevron pattern. All of the wire strands of the single exception are twisted single, but they are not twisted together to form a rope pattern; the hoop of this piece is double rather than quadruple, and it does not have a chevron pattern. Although one of the pendants is slightly broken, it seems that each originally had three cylinders of soldered wires on top which acted as spacers for the necklace strings from which they hung. Many gold and silver examples of this type of pendant, one with its wire strands twisted in the manner of our exceptional piece, were found in the Early Dynastic tombs at Ur. Two of these, not the closest of the parallels, are in the University Museum’s Mesopotamian collection and were recognized immediately by Professors Machteld Mellink and Ellen Kohler when they saw the new Trojan jewelry. Some of the Sumerian pendants differ only in that their spacers were usually of solid strips rather than formed of soldering wired. There can be little doubt that all of these pendants came from the same source, for the basic design with its embellishments is rather complex and not likely to have been invented independently at Troy and Ur. Because of their frequency at Ur, it seems that Mesopotamia was their source.

The last piece in our new collection is an unusual earring made of five wires, each formed of curled sheet metal, soldered together in a shape much like that of our “shell” earrings of Trojan type; a typical applique boss was added to the “shell.” From the wires protrude five tiny rods, each scored with fine lines, which spread apart slightly just before ending in touching nail-head-like ends. Hanging from rings attached to these ends are loop-in-loop chains ending in leaves of sheet metal decorated with repousse dots (one of the chains is broken, and its leaf missing). Only one parallel for this piece has been found and that is a “unique” earring form the Early Dynastic cemetery at Ur. Now in the Baghdad Museum, the Ur earring also has the scored rods protruding from its wires; it also has a boss, but in addition it has a pair of applique spirals, making it reminiscent of the earring in the new University Museum hoard described in an earlier paragraph. These pieces are typical of neither Trojan nor Sumerian earrings, but they seem more Trojan in appearance Thus there is the possibility that there were not only imports from Ur at Troy, but imports from Troy at Ur in the Early Bronze Age; more probably, perhaps, is the possibility that these earrings came from a common source which remains unknown.

It is, of course, not known if Trojan jewelry was actually made at Troy and Poliochni, but it seems likely that it was made somewhere in or near the Troad. Although certain techniques were held in common by all, it is almost certain that the various regions which have produced fine metalwork during the Early Bronze Age had their own local craftsmen; the gold sauceboat from Arcadia, for example, could only have been made in the Cyclades or ont he Greek mainland, the two areas to which such sauceboats in terra cotta were restricted. Crete seems to have had its own less advanced goldsmiths, and Alaca Huyuk, although partially coinciding with Troy II in time, seems to show more in common with neighboring Amasya and with Maikop in southern Russia than with Troy.

On the other hand, a recently published Early Bronze Age jeweler’s mold from Anatolia contains negatives for casting separate metal pieces, some of which would have been more at home at Alaca, others in the Troad, and still others in Mesopotamia. This indicates that one goldsmith could produce wares for the separate markets, but whether he travelled between them or merely exported in various directions is not known.

Obviously much is yet to be learned of early trade in jewelry. It has been assumed by most authorities, for example, that techniques of fine metalworking spread from Mesopotamia throughout Anatolia and the Aegean, the assumption based on the fact that the Ur jewelry was the earliest. Now we see that Trojan jewelry was being produced at the same time, and that some of it may have been sought by the Sumerians of Ur. It is just possible, therefore, that the goldsmiths who made the jewelry for Troy, whether they lived in the Troad or at some point between Troy and Mesopotamia, may have had a hand in the development of some of the fine techniques such as filigree and granulation, whose origins are not known.

The chronological implications of the new hoard are also of significance Troy II, the uppermost of whose layers produced Schliemann’s treasures and the fewer but similare finds of the University of Cincinnati expeditions, has never been securely dated. The controversial, privately excavated Dorak treasure from an unknown cemetery near Troy, never fully published, contained cartouches of two Egyptian pharaohs known to have lived around 2500 B.C. or shortly thereafter a date not incompatible with that of the Ur cemetery with which it has certain features in common. Dorak also contain objects similar to some from Troy II, and thus an early date for Troy II might be expected, a date which would have some bearing on the partially contemporaneous cemetery at Alaca Huyuk and, therefore, possibly on Maikop as well. Recent studies have indicated, however, that Troy II is contemporary with the Akkadian period of Ur which immediately followed the Early Dynastic period, a time when trade between Mesopotamia and Anatolia is known from written documents. The Trojan jewelry was not necessarily new, however, when it was finally stored away to remain for over three thousand years, and there is no reason to doubt that the end of Troy II did, indeed, coincide with the Akkadian period; but it now seems most probable that at least some phases of Troy II overlapped some of those of Early Dynastic Ur, and it should be recalled that the exact chronological position of the “Royal Cemetery” during the third and last phases of the Early Dynastic period has never been placed with certainty.

A fuller discussion of the significance of the new jewelry must await its detailed publication, now being prepared, but we feel that the friends and members of the University Museum should be the first to learn of their valuable new acquisition through this report in Expedition.

- Necklace of 220 beads.

- Ilios, p.462, #746-751.

- Pendants, each about one inch in diameter.

- Pendants, each about one inch in diameter.

- A pendant from Ur in the University Museum Mesopotamian Gallery.

- Earring (left), slightly more than two inches long, compared with earring from the “Royal Cemetery” at Ur, now in the Baghdad Museum. The newly acquired earring is shown actual size on the cover.