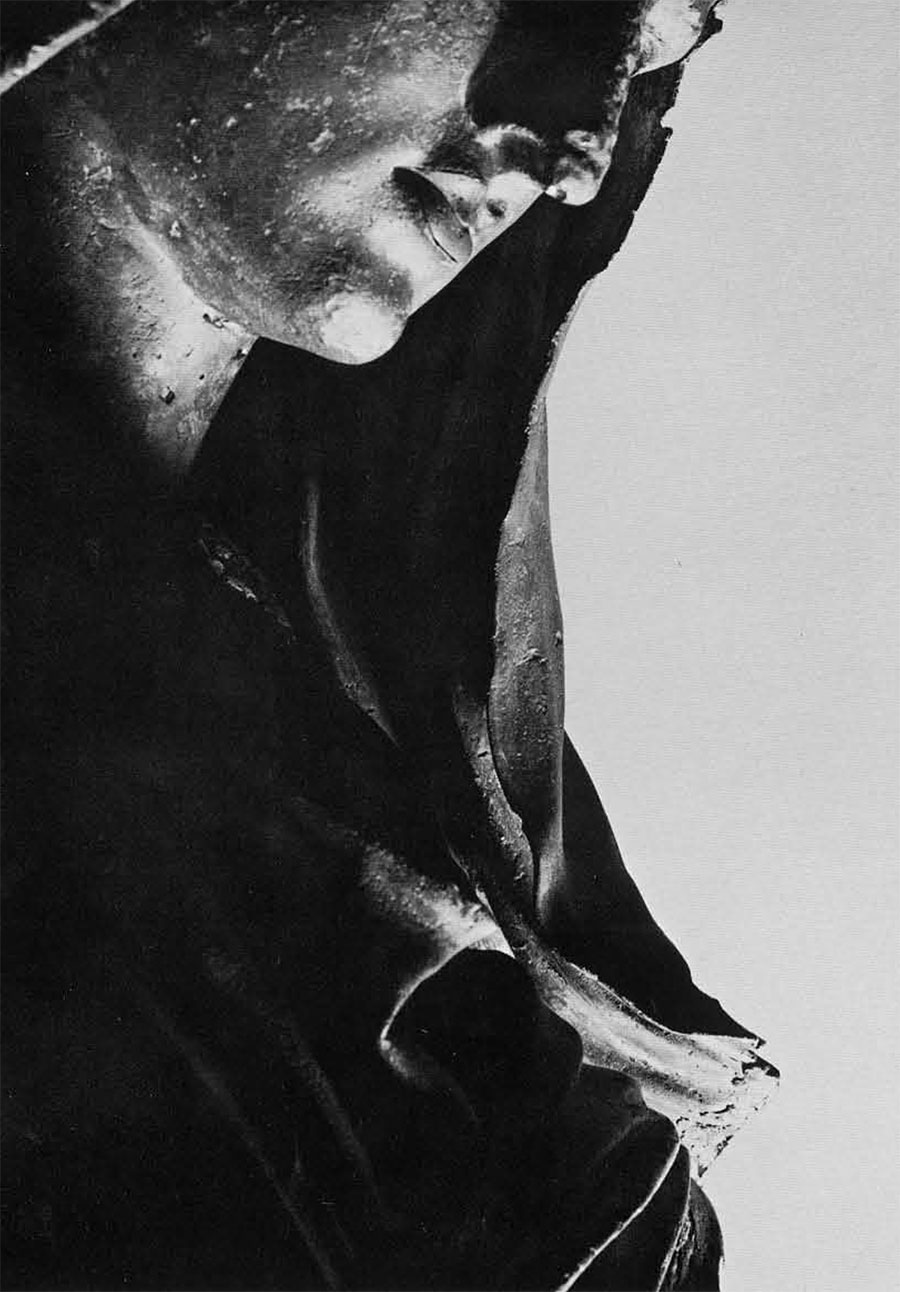

Visitors to the University Museum between October 16 and November 27, 1966, had the opportunity of admiring one of the most exciting pieces of Greek sculpture discovered in recent years. Among the many important items of the Traveling Exhibition “Treasures of Turkey,” sent by the Turkish Government and selected by University Museum members Professors Rodney S. Young and Machteld J. Mellink, was the over-life-sized torso of a female statue of great beauty, a bronze Greek original of the early third century B.C. In keeping with its importance the figure was displayed in isolation, within a small room, in a semi-darkness broken only by cleverly focused spot-lights which brought the main features into sharp relief, but allowed deep shadows to form within the folds of the veil covering the statue’s head. This setting may seem romantic, but equally romantic is the story of the statue’s discovery.

The veiled lady came from the sea. It was found on August 9, 1953, by some fishermen dragging their nets for sponges along the coast of Asia Minor, not too far from the Knidian peninsula. The fishermen were not pleased: they did not realize the importance of their discovery and just begrudged the damage to their equipment. They brought the bronze to the village of Bitez, near Bodrum, and left it on the beach, where it lay, neglected and covered with incrustation, until it attracted the attention of George E. Bean, the British Professor of Istanbul University. He immediately realized the importance of the find, published an account of it in the Illustrated London News for November 7, 1953, and had the bronze removed to Izmir where it was cleaned and catalogued as item No. 3544 of that excellent museum.

Greek originals are rare. Most of the famous works by renowned ancient sculptors are known to us only through the so-called “Roman copies”; commercial imitations, often in a cheaper material, made by artisans of various nationalities for their Roman clients. Though some of these replicas may achieve a great degree of accuracy and even beauty, many of them are simply decorative work, meant for the outdoor settings of luxurious villas. Their backs are often perfunctorily treated because the copyist knew that the statues were to be set up in niches. Sometimes a portrait head was inserted on a classical body, to please a philhellenic patron. Always the vigor and freshness of the prototype were somewhat altered by the mechanical process of reproduction. For us today, finding a Greek original of the Pre-Christian era is a major event.

Greek bronze originals are even rarer. Once the appreciation for the artistic value of the statue was gone, the appreciation for the material took over, and ancient bronzes were almost invariable re-melted, either to be made into different statues, or to be used as metal. Our chances of finding a Greek original bronze, under normal circumstances, are almost nil. It takes a catastrophe—an earthquake or a shipwreck—to preserve a bronze, either under the earth or in the depths of the sea: a landslide saved for us the Delphi Charioteer, and the Artemission Zeus was rescued from the waters of Euboea.

Our bronze Lady undoubtedly was shipwrecked in antiquity. We may never know whence she came and where she was going, but it is plausible to assume that she was being taken to Rome, perhaps from some famous Hellenistic center in Asia Minor. The statue suffered greatly in its misfortune. It lost the lower torso from just below the waist, the whole rear part of her body, both arms and, with those, perhaps also her identity, since no objects, such as perhaps a scepter or a sheaf of wheat, now remain to give us a clue to her name. Who is the Lady from the Sea?

The slight bend of the head, the downward gaze, the veiled hair suggested to Professor Bean the name of Demeter, the sorrowful mother of Kore mourning her kidnapped daughter. The obvious comparison was at hand: from Knidos, therefore from near the finding spot of the bronze, once came a marble statue of a seated Demeter now in the British Museum in London, who also has her hair covered, in sign of mourning. It was easy to assume that we were dealing with the same type, if not with a work by the same artist.

The London Demeter is a controversial piece. Usually dated in the fourth century B.C., and variously assigned to Skopas or Leochares, it has recently been attributed to the Hellenistic period, around 100 B.C. Though this theory has not met with general favor, the discovery of the Lady from the Sea gave it apparent support, and it could be suggested that the marble statue had been made to replace the bronze when this latter was removed, perhaps forcibly, by the Romans. We know in fact of many cases in which famous statuary was appropriated by greedy emperors, who left instead a replacement of some sort, often in a cheaper medium.

Appealing as this hypothesis may be, a comparison between the bronze and the marble statues reveals many differences. For instance, the attire of the two women is different, the Lady from the Sea being more voluminously dressed. The hairstyle and inclination of the head also vary, while the head-covering is a veil in one case, a loop of the mantle in the other. Finally, the bronze seems to represent a standing figure, in obvious contrast to the seated pose of the British Museum Demeter: enough of the torso is preserved below the waist to show that the metal did not curve outwards as would have been the case in a sitting position. Had the marble been a replacement for the bronze, it would have imitated its prototype much more closely.

There is also no assurance that the Lady from the Sea is Demeter. This goddess is usually shown with her mantle drawn over her head, as in the British Museum statue; but the newly found work wears a veil, striking in its wind-blown effect, which is fairly unparalleled in Greek statuary in the round. Figures in motion are often portrayed with flamboyant drapery, it is true, or coy ladies are shown pulling their veil aside with one hand; but our matron stands in a quiet posture, and the veil gives no indication of being grasped by her fingers. In the lack of cogen parallels, one might suppose that the bronze statue represented a mortal lady, perhaps the wife or mother of a Hellenistic ruler, and was either an honorary or a funerary monument.

The most intriguing aspect of the Lady from the Sea lies however not in its date nor in its identity, but in its technique. Since our knowledge of ancient bronze is scanty, it had long been assumed that statues were cast in one piece, or in as few pieces as possible. For instance, a nude male figure would have arms, legs, and head attached, but the trunk would be a unit. Draped figures might dissimulate a joint at the waist under a belt, but again the skirt area would be whole down to the inserted feet. Moreover, bronze statues preserved in more or less intact condition would be cleaned and mended from the outside, but no real examination of the interior would or could be carried out. The Lady from the Sea, because of the loss of her back, appears almost like an elaborate breastplate with a head: one can look inside it, and the ‘introspection’ is revealing.

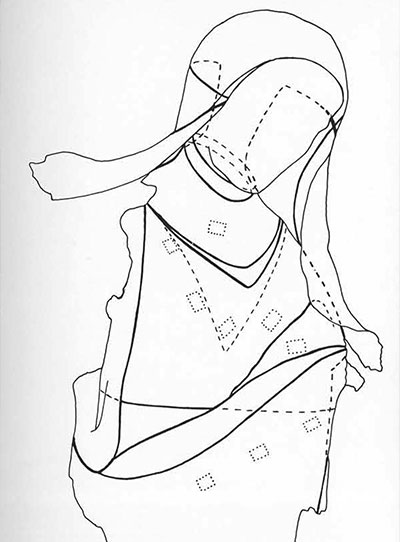

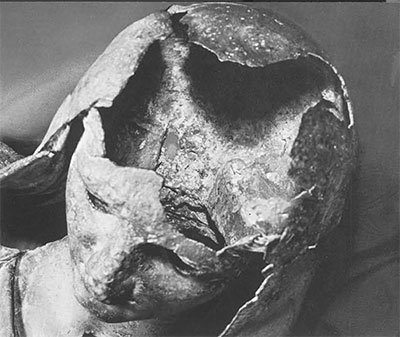

It is hard to believe from the exterior appearance that the statue could be made of so many pieces. The artists were most successful in dissimulating joints and patches, either for imperfections in the bronze or for vents and pouring channels. The figure is a veritable mosaic of separate parts. Her head is hardly more than a face mask, whose cranium is formed by the separately added veil. The veil itself is composed of three pieces: the main panel over head and nape, and the two lateral flaps, joined to the main part over the area of the temples. The head thus formed (that is, the combination of face-mask and veil) rests on a sort of round collar, of uniform height, which in turn rests on the base of the neck. This latter expands into the triangle of the chest, larger on the inside than it appears on the outside, since it is sunk into the drapery which constitutes the torso. Between the chest area and the edge of the heavy V-folds of the main dress a sliver of metal, inserted from the outside suggests the crinkly material of a thin undergarment. A voluminous mantle forms a roll of diagonal folds which cover the left breast and cross under the right one, to disappear over the right flank. There the bronze folds merge rather haphazardly into the rest of the metal, presumable because that side was once covered from view by the lowered right arm. But even in this homogeneous-looking roll there are added pieces: the two topmost folds are hollow and cast separately; they were later attached to the main section of the garment, but gaps were left between layers and a thin thread of light filtering through now reveals the ‘manufacture’ of the mantle to the attentive observer. Similarly, the long vertical fold coming down from the right shoulder along the breast is a separate piece, most likely once matched by a comparable pleat on the opposite side.

But the most unexpected joint of all occurs at the level of the breasts. Completely invisible from the outside, it appears on the inside as a thin line through the middle of the right breast, and it can be traced with reasonable certainty almost all the way across to the left side. One should pay tribute to the skill of these ancient bronze casters: their joints are difficult to detect even from the inside, and even when one is alerted to their presence and looks for them. The technique is so perfect that one can never be absolutely sure of having perceived all devices or noticed all details.

We may now try to reconstruct the ‘birth’ of the statue in antiquity. The sculptor, presumably, made a model of plaster or, more likely, of clay which, when leather-hard, was cut into separate pieces. From these pieces moulds were made, which, because of their relatively small size and simplified nature could often be used for solid casting. Here the value of the sectioning becomes apparent: to cast an over-life-sized statue in one piece requires an extremely complex mould and a large core. By fractioning the same statue into pieces one can in many cases avoid the use of a core, and thus also of many vents and sprues. Let us consider, for example, the veil of our Lady from the Sea. Had it been cast as a whole, it would have been very difficult to control the flow of the molten metal between head and veil, and several pouring channels might have been necessary. By casting it in separate parts, the two lateral flaps and the main central piece became virtually flat sheets of bronze which could easily be cast solid and then reassembled.

Some pieces were nonetheless too complex for this procedure, and required sprues. These pouring channels leave rectangular openings in the surface of the finished bronze which demand patching. The caster accurately filled many of these holes, and the patches have held in most cases; one in the chest, at the base of the neck, has fallen off, thus alerting us to look for others, which appear as faint rectangular outlines on the interior surface of the statue. Many such patches have been noticed; others almost surely have escaped detection. By studying the pattern formed by these mends one can acquire a fairly accurate idea of casting principles and methods in antiquity.

When all the pieces were cast and reassembled, and the outer surface had been scoured of the so-called ‘casting-skin,’ the final details were added. The eyes were inserted from within, presumably made of marble or vitreous paste enclosed in a lead or silver frame; the lips were lined with red copper to provide a color contrast to the rest of the face’ and at some stage prior to the assembling of face and veil, the hair over the temples had been engraved into soft-looking waves. A work of art emerged, a statue of great technical perfection, beauty, and apparent unity. No one, from the outside, would realize that it was made of so many parts. And in this respect—from the point of view of our constant search into the methods and techniques of the past—it is almost fortunate that its later vicissitudes brought the statue to us in its present mutilated state. The knowledge we have thus gained can perhaps repay the loss of the aesthetic enjoyment we would have derived from the whole.