After nearly twenty years of activity at Gordion it is perhaps well to look back, to recall the reasons for our choice of the site, to weigh results against expectations, and to assess what we have learned.

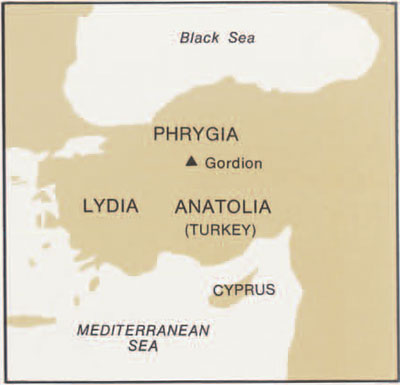

In the fall of 1948 we had four sites in mind, all of them capital cities in ancient times: Cyrene, Gordion, Sardis, Xanthos. The last three gave promise of yielding information about the unknown dark age of Anatolia, between the fall of the Hittite Empire in the twelfth century and the rise of the Greek settlements of the west coast in the seventh. Gordion and Sardis had been tested by earlier excavators in the first years of the century, and a little was known about them. A visit to Gordion in December 1948 with John Daniel and Roger Edwards resolved the question as to which of the four sites we wanted. At Gordion a large settlement mound, virtually untouched; on the hills and ridges around it the grave tumuli of royalty and of the rich to the number of more than eighty and in varying sizes. A special challenge was the Great Tumulus which had drawn the German excavators, the brothers Koerte, to Gordion in 1900 and which, after due consideration, they did not attempt to dig as being beyond their means.

All the region in December 1948 was covered by snow which prevented the gathering of surface potsherds which might indicate what was to be expected beneath. A later visit in May 1949 was also disappointing in this respect. Very few sherds were found on the surface, and these for the most part were coarse and enigmatic. None the less we were able to report to the Board of the Museum that the site was promising, a large center of major importance over a period almost unknown to history and which might take many years to dig. This it has done.

In the first year the city mound showed four major levels of occupation: Hellenistic, Persian Empire, Phrygian, and Bronze Age. Over the years, excavation of the first three levels has been greatly expanded, the fourth has been tested. Each level has its own importance and each has produced its own surprises and major finds.

The Hellenistic settlement came to an end in 189 B.C. when the site was abandoned at the approach of a Roman army come to chastise the Galatians. Gordion thus affords a fixed point in the chronology of Hellenistic Asia Minor; except in certain limited areas which were resettled later, nothing from the Hellenistic levels should be dated later than 189 B.C. This is borne out by the hoards of coins found on the site. Altogether seven hoards have been recovered, five of them including coins which run down close to the end of the third century. These collections of money seem to represent the mercenary pay of the Galatians, or the loot they took on their raids. One hoard, of gold, included two eight-drachma pieces of Antiochos I and of Seleucus III; it was not known before their discovery that gold coins of this denomination had been struck by the Seleucid kings, and a lone specimen which appeared on the market had been cold-shouldered as a probably forgery.

The city of Persian times was walled around, with a main gate at the southeast side. The buildings were large, substantially made of cut stone, for the most part on a “megaron” plan of outer vestibule leading in to an inner room with a central hearth. Plan and type of building as well as the general layout of the palace area were thoroughly Phrygian in style, as was shown when the earlier city beneath came to light. This must have been an important garrison and market town of the Persian Empire, perhaps the seat of a district governor It was strategically situated on the Royal Round from Susa to the west, organized by King Darius, over which the business of the Persian State with the far provinces was transacted. A stretch of Darius’s road has been uncovered at Gordion, and its course has been traced for many miles toward the east and the west.

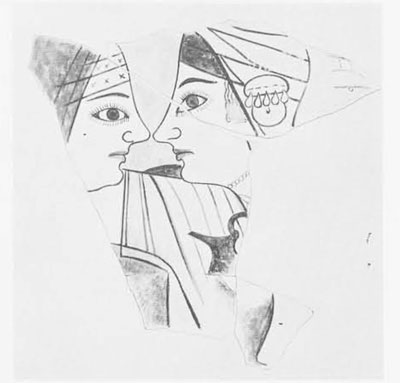

An innovation of the time of the Persian Empire was the use of moulded and gaily painted architectural terracotta tiles, no doubt made under Greek influence. One of the buildings at least was decorated inside by mural paintings on the stucco wall face. Countless fragments of painted wall plaster were collected: enough to make up individual figures and fragments of figures, but not enough to restore the general composition. In style and technique these wall paintings are Greek of the beginning of the fifth century, though the subject matter is local; probably they were executed on commission by an itinerant Greek muralist.

The coming the Persians to Phrygia was rather dramatically illustrated on the smaller mound to the southeast of the city, evidently a suburb in Lydian times. Here there had existed a great fortification wall of crude brick, more than forty feet in height. On a platform against its inner face, and with direct access to the ramparts, stood a building with many large rooms, which seems to have been the barracks of a Lydian garrison in the first half of the sixth century. The building had been burned after a battle; countless bronze arrowheads were found embedded in the wall faces. The whole had been buried (hence its good preservation) under a tumulus, no doubt made to cover the grave of some magnate killed in this battle. All this (the Lydian pottery told us) happened at about the middle of the sixth century; no doubt the battle took place during the march of Cyrus the Great to Sardis in 547-46 B.C. He was probably following the old route to the sear which was later organized as the Royal Road.

The Phrygian city at Gordion was destroyed in a raid by Kimmerian nomads at the beginning of the seventh century. Over the years a large part of the palace area has been opened up: seven large buildings on the megaron plan, spaced around three sides of an open square within the city gate, have been exposed. On a terrace behind them at the south stood two huge service buildings in which the work of the palace was done—the grinding of flour, the kneading and baking of bread, the weaving of cloth, the storing of pottery and other utensils. The richness of the appointments of the palace itself was suggested by the large numbers of painted vases, the charred fragments of sumptuous furniture decorated by carving in relief or inlaid with plaques of ivory carved in a specifically Phrygian style, the crushed remnants of vessels of bronze, the burned shreds of cloth hangings woven in intricate patterns and once-gay colors. Some of the buildings were paved with floors of pebble mosaic in elaborate geometric patterns; these are the earliest patterned mosaic floors to have been discovered up to the present, and mosaic-making may have been a Phrygian invention. The limits of the palace area at west and south were defined only in 1967 by the discovery of sections of the enclosure walls which divided it off from the rest of the town. Since excavation up to the present has been concentrated almost entirely in the area of the palace it is to be hoped that digging in the town without may bring to light some of the workshops in which the furnishings of the palace were manufactured.

The tombs of Phrygian times, undisturbed, contained intact objects of the same types as those found in such pitifully burned and fragmented condition in the palace. Three major and one minor tombs of this period have been opened. The greatest, covered by a tumulus still 170 feet in height, invited new techniques: drilling with a light oil rig to locate the position of the tomb within the mound, and tunneling to reach the tomb without destroying the overlying tumulus. The tomb was intact: a construction of finely trimmed and fitted timbers with a gabled roof, protected without from the pressure of the material piled around and over it by a casing of trimmed logs. The techniques of tomb construction—the mortising of the corners, the finishing of wall faces with the adze and by sanding—give us much information which can be applied in the reconstruction of the burned buildings of the city. A tomb on this scale can have been made only for a king; for various valid reasons we have dated it between 725 and 717 B.B. The many bronze vessels offered as tomb gifts included cauldrons with siren or demon attachments, or bull’s head attachments—a class of vessel well known and widely disseminated through the Mediterranean area, but never before pinned down as to date. Many types of bronze vessel (and of bronze fibulae or safety pins) were specifically of Phrygian manufacture: Phrygia, and probably Gordion itself, was an important early center of bronze-working. In addition to the bronzes the tomb contained much wooden furniture—screens decorated with elaborate inlay of wood in geometric patterns, tables, and a great four-poster bed on which the body of the dead king had been laid out. The tomb of a royal child, slightly later in date, had been filled with objects calculated to delight the fancy of a child—pots in the form of animals and birds, wooden utensils (including a spoon) and carved animals which may have been the child’s playthings in life.

Most important of all, the Great Tumulus contained five alphabetic inscriptions in Phrygian, demonstrating that before the end of the eighth century the Phrygians were not entirely illiterate and raising again the question as to where and when the early Semitic alphabet was adapted to the use of the western world. The Phrygians are now shown to have been master craftsmen at working in bronze, in ivory, and in wood; skillful and imaginative potters; innovators in mosaic decoration; masters of architecture both in the planning and the fine execution of their projects whether of a military or of a domestic nature. Their further development was cut short early in the seventh century; but the results at Gordion have shown them to have been leaders and major contributors to the development and transmission of material culture in the formative eighth century. With deeper probing of late years we are beginning to realize something of the antecedents and to follow the various steps in the development which led to this flowering of Phrygian culture. More work in the earlier Phrygian levels is necessary; and beneath lies a complete stratification leading back through the Hittite period and into the Early Bronze Age. But thus far this has only been tested. As the excavation at Gordion proceeds the prehistorians too will have their day!