At the airport in Tripoli I met the three husky young Italians who were to accompany us into the desolate reaches of the Sahara in southeast Libya. Bruno Finnochiaro is a veteran in Land Rover exploration in Africa; Renato D’Arcangeli, the Pan-American Manager in Tripoli, was a neophyte in this kind of land travel, but he came well equipped with a five gallon jug of Italian wine; Angelo Pesce is another veteran of desert travel and a geologist with an infectious enthusiasm for the desert. The night before, Jean Newsom, the wife of the U. S. Ambassador, had insisted I retire with a whole battery of books about the area we were to explore, and two of them had been written by Pesce. Thus it was a pleasure to find myself seated with Angelo in the Libyan plane en route to Sebha in the Fezzan, so that I could question him about something which had been puzzling me ever since my last venture into the southwest Libyan desert.

With Dr. Mohammad Ayoub, Director of Antiquities in the Fezzan, I had seen the ruins of a city in the Murzuk Sand Sea which probably cannot be older than the Roman period and which, Ayoub believes, must have been based upon the use of horses. It is now a waterless waste. Just when did the greatest desert in the world reach its present arid state? The famed rock carvings and paintings of the Tassili and Tibesti Mountains certainly portray a land where many animals and men lived during and after the Ice Age and we can be quite certain from Egyptian records that there were herds of domestic cattle in the Sahara some four thousand years ago. Angelo Pesce discussed all this in terms of the geological evidence while we flew south over the green belt along the Mediterranean, then the area of scrub trees and camel thorn, and finally the lifeless desert. But from the unanswerable questions about the fluctuations in desert aridity we soon moved to talk about the strange land we were about to visit. There were four principal objectives: Waw al Namus (spring of the mosquitoes), the weird depression left by an exploded volcano, Egi Zuma, source of the Carthaginian stones once considered more precious than diamonds, the Tibesti Mountains on the border of Chad, and Kufra Oasis where new wells are now making the desert bloom again. As an archaeologist, I found the idea of Egi Zuma the most exciting. Mines which produced those famous stones for centuries certainly should be associated with some sort of ancient archaeological site.

In Sebha we landed at a new and impressive airport to be met by Dr. Ayoub and the Governor. They were expecting the U. S. Ambassador, David Newsom, who had organized this safari into the desert and whose guests we were. But the Ambassador was with the first fleet of Land Rovers somewhere between Tripoli and Sebha expecting to arrive in Sebha that evening. Ayoub’s Antiquities Service guest house was all very familiar after my earlier trip into the desert, but Sebha, with its new airfield, hospital (manned largely by Chinese doctors and nurses), new government buildings, experiment stations, etc., had changed dramatically in two or three years. It is now a rapidly growing center for the string of oases known as the Fezzan and the largest settlement in all southern Libya.

We spent the afternoon and evening preparing and sorting out equipment for the combined expedition which was to leave Sebha for the south and east sometime during the next day. Not until midnight did David Newsom’s party finally arrive at the guest house in four Land Rovers. With him were Dr. Kenneth Dod, a physician from California (with all his medical kit), Lt. Colonel Jack Mansfield, U. S. Air Force, Lt. Colonel Robert Wells, U. S. Army, Rocky Sudduth, Second Secretary at the U. S. Embassy, Bob Sanberg, Embassy Communicator in charge of the radio which was to keep us in touch with Tripoli, and Walt Gish, a dentist who is also a skilled mechanic and a whiz at nursing ailing Land Rovers. Dinner had been kept waiting by Ghaith Sayf an Nasr, Governor of Sebha, and so at 12:30 A.M. we all sat down to a Fezzanese dinner of five courses which kept us up until nearly three in the morning.

That morning, January 7, all of Ambassador Newsom’s party assembled at the Antiquities rest house to redistribute the load among eight Land Rovers and two large Bedford trucks supplied by the Fezzan Police Department. The group from Tripoli and abroad was then joined by Dr. Ayoub, two of his assistants from the Antiquities Service, two drivers, a cook, and eight police, making a total of 26 men in ten vehicles. The gasoline, water, food, and camping equipment for such a party expecting to travel for about two weeks over some 3,000 kilometers in the desert was indeed a difficult logistics problem. But both Newsom and Ayoub are old hands at this kind of expedition and it was obvious we would lack for nothing after their careful planning. A new wrinkle, at least for Ayoub and me, was the radio equipment, not only Newsom’s long-range apparatus for communication with Tripoli and the police radio for contact with different police posts, but three short-range sets for communications between vehicles in the convoy. The value of this latter was to be proven many times when vehicles became scattered over twenty or thirty kilometers of desert and when two or three at once would become bogged down in soft sand.

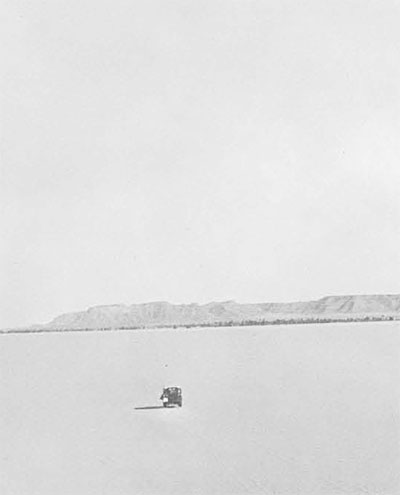

All of us I am sure had the same exciting sense of adventure when the whole convoy left the roads at Sebha and struck out across the desert toward Zueila. Normally two men rode in each vehicle and spelled each other driving. Several of us had our first experience in the tricky business of managing a Land Rover on the varying desert surfaces. The conventional idea of rolling sand dunes is, of course, true in certain areas but this is only part of it. There are the high plateaus with a pebbly surface which sometimes looks almost like a mosaic floor, or the high rocky ground called hamaada which is very slow going and very rough on the Land Rovers. Then there are those marvelous flat stretches of cream-colored sand which are as fast as Daytona Beach, and also those surprises for the neophyte called feshfaash, areas of soft sand where you find yourself suddenly bogged down to the hubs.

But the most exciting driving is in the dunes. I remember one long stretch in the Rebiana Sand Sea which was like the Pacific Ocean with its long swells and the great rolling combers where swells strike a sunken reef. The rule is to drive flat out hoping the next swell is not a comber. But in the big dune ridges, streaming sand from their crests in almost any wind, one must pick just the right part of the troughs and the slopes to avoid feshfaash and the humiliating affair of calling for help to get yourself unstuck. In most desert driving there is a great sense of freedom—you can turn in any direction and there are no worries about traffic. Riding as copilot with Jack Mansfield one morning I noticed a rare desert fox off to our right. At once we swung out of the route of the convoy in pursuit of the fox who led us a merry chase over a rolling landscape twisting and turning. When he tired we wished him luck and picked up the tracks of the other Land Rovers which had disappeared over the horizon.

But there were risks. Driving south of Kufra with two Land Rovers, our Tibu guide noticed that the leading car had turned into a very soft stretch of sand and he urged me to head it off. At that point there were four of us in Jack Mansfield’s Rover and each one had his own idea of just how to hit the dunes. Trying to follow all the advice at once, I headed up the flank of a dune ridge at top speed, then heard someone shout “turn right,” and a moment later sailing parallel to the slope I felt the Rover just beginning to roll over—the slope was steeper than it had appeared in the featureless sands. A quick turn downhill saved us, but Jack said afterward he was already trying to figure out how we could extricate ourselves from that mess. One of the problems in dune driving is the lack of perspective where there are no distinct features like rocks or grass or bushes. Slopes, ridges, swells, and heights are often distorted by illusion. This is also true on the absolutely flat stretches which may extend for many miles. On one such plain we drove for some 200 kilometers, always with the feeling that we were constantly driving uphill out of a small bowl. Not until we sighted oil derricks in the far distance did this illusion disappear.

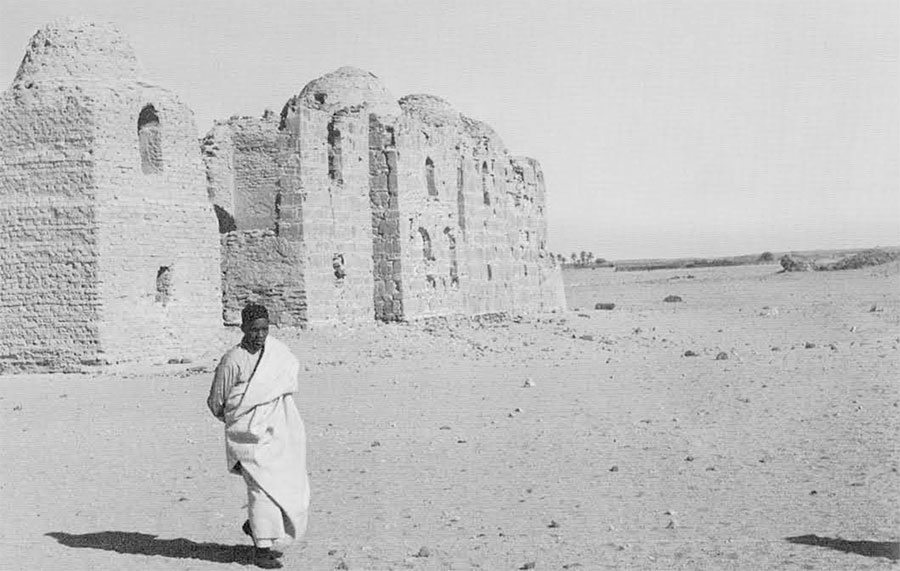

Zueila, which Ayoub and I had visited during our earlier travels in Libya, is an ancient settlement in an isolated oasis built in early Islamic times by the Bani Kuttab, but here there is also an extensive ruin of an earlier Byzantine town which could well repay excavation. Pottery, beads, and other artifacts of the Byzantine period are found all over the low mounds marking the most ancient site. As before, we were entertained at dinner by Saiyid Sherif in his house at the center of the town in a kind of mediaeval setting—a large room furnished with rugs and cushions where we lay on the floor waiting for huge copper platters of rice and mutton. It was surprisingly cold—almost down to freezing—so that the charcoal braziers and hot cups of tea were very welcome.

There were tracks on the sand to follow from Zueila to Waw al Kabir, the next oasis where we found the last police post, and the last settlement until we reached Rebiana several days later. Our Tibu guide had relatives in Waw aI Kabir and during our brief stop Ayoub talked with them about Egi Zuma and those precious Zuma stones. I was amused to watch Tibu men consulting their veiled wives, well removed from us outlanders, and then to watch them approach Ayoub with women’s things to sell. Among these was one necklace with a pendent green stone. We were told it was a true Zuma and the price set certainly indicated an extraordinary value in their eyes. My interest in the mines increased when it was evident that the Tibu, ancient people of the Tibesti Mountains, still wore the green stones as charms.

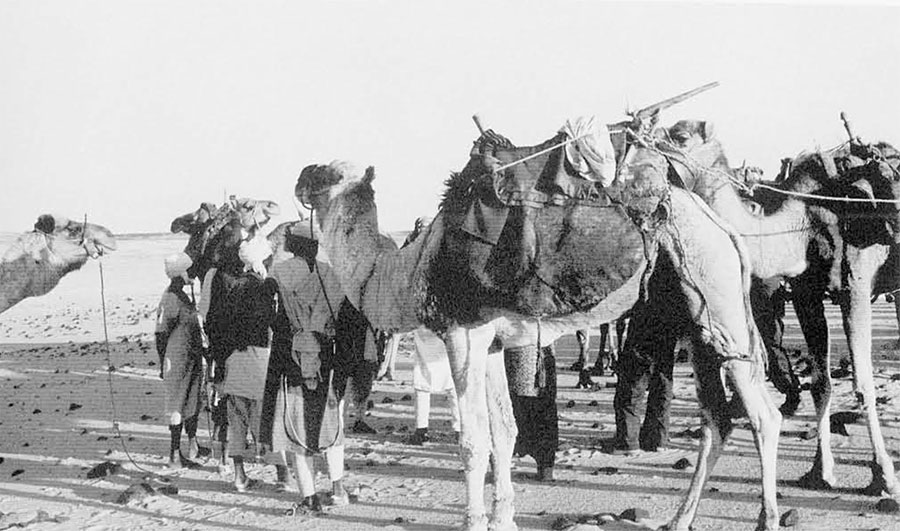

That afternoon we struck off into the desert again, headed on a compass bearing for our first objective, Waw al Namus. Late in the day we found a wadi with many dead trees, a kind of mimosa, which were to supply us with many a cheerful campfire at night in the chill wind after the sun had set. We were lucky to have the Bedford trucks to haul firewood as well as water and gasoline. Searching for a sheltered campsite that evening we encountered a Tibu camel caravan from Chad en route to Waw al Kabir. In moments the caravan was surrounded by our whole group of 26 men—the Americans photographing and the Libyans bargaining for a goat or a sheep. We ate a sheep that night, broiled over the fire within the circle of vehicles which reminded all the Americans of those circles of prairie schooners on our western plains.

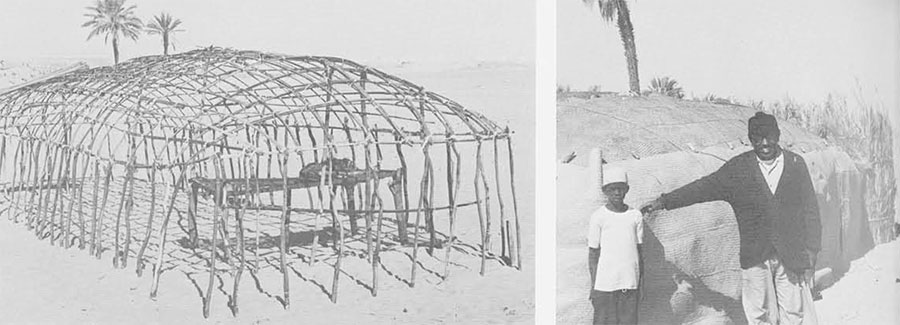

The whole effect of Waw al Namus is weird. Quite suddenly we seemed to be in the shadow of a cloud, but the sky was clear and looking closely at the desert sand I noticed that it had changed from yellow to black with a thin surface layer of what looked like coal cinders. Then, after crossing about ten kilometers of this black desert, and without warning, we were abruptly halted by a huge crater perhaps three kilometers in diameter and some 300 feet deep. In the center rose a brown volcanic cone surrounded by a series of narrow crescent-shaped blue lakes. There were occasional date palms and bamboo growing about the lakes and one small hut. The dark sand, the isolation, and the obvious record of what had happened there all contributed to the awesome spectacle before us. After one vast explosion a second volcano had grown in the deep lake of sub-surface water exposed by the blast. I was reminded of Santorini and Krakatoa. Several of the Land Rovers swept down into the crater and we watched them with field glasses as they explored the lakes and then made their dash up the steep slope to the rim. They resembled small grey bugs scurrying about in a vast black bowl. One man, with his two wives and two children, is stationed in the crater during the winter months by the Senussi Zawia at the Waw al Kabir. With them are chickens, sheep, and camels.

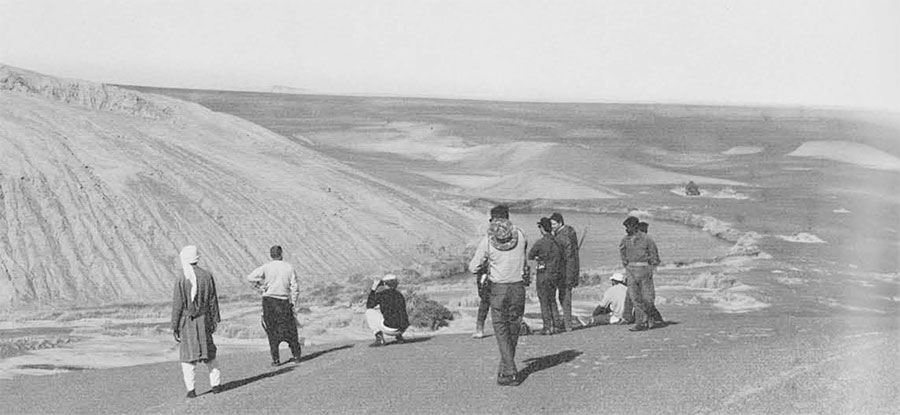

Again, navigating by compass, we struck out for the track, marked by Italian troops during the last war, which would lead us to a pass through the northern part of the Tibesti Mountains. But the crossing was not easy. In one dune ridge practically all the vehicles were stuck at one time or another and there was much chatter over our intercom system. “Rover One calling Rover Four—we are standing by the two trucks which are both down and working their way out with the metal sand tracks. Where are you?” “Rover Four to Rover One—we are at kilometer 141 (as marked from the starting point that morning). We have three Rovers stuck. Bob Sanberg is out of beer. Ken (Dr. Dod) is off hunting rocks. We will check back in 15 minutes. Over and out.” The last part over a rocky homaada was brutal for the Rovers. Sharp and jagged rocks, green-grey boulders to work around, ancient stream beds to cross, and the constant shifting of gears through four-wheel drive and low low. In the distance black and rugged peaks of the Tibesti began to appear. Then suddenly in a shallow wadi, two days out from Waw al Namus, we saw a patch of feathery grass, the first living thing in all that distance. We all stopped to admire and were struck by the fact that living things all go together. With grass there were birds, insects, rodents, camels (left to pasture by the Tibu) and herding with the camels, those beautiful wild desert creatures, the gazelles.

Toward evening we raced across a creamy-yellow stretch of sand to the base of a Tibesti mountain range which rises straight out of the sand like a reef at sea—barren black rock, sand-blasted into weird, jagged forms like ruined towers, turrets, and boulders broken by some giant hand. One peak we called the ‘Cathedral’, but to me it looked more like the back of a vast dinosaur rising out of the sand. I had been riding with David Newsom and as I stepped out of his Rover there was a crunch under foot. Looking down I saw a large piece of neolithic pottery with the familiar punctate decoration. In a few moments it was clear that the sand was littered with potsherds, flint chips, and fragments of grinding stones made by some ancient grain-growing people.

That was our best campsite in the desert—our tents pitched on the bright sand in the moon shadow of jet black peaks—grotesque rocky forms all about us—and the anticipation of discovery when the sun rose next morning. Dawn, as usual, found Kennie Dod on top of one of the peaks and the rest of us shivering around the campfire waiting for hot coffee. Angelo Pesce and the Tibu guide, in one Land Rover, left early in search of Egi Zuma which could not be far away. The evening before we had all searched through one vast wadi with endless branching offshoots into the mountains, without any luck.

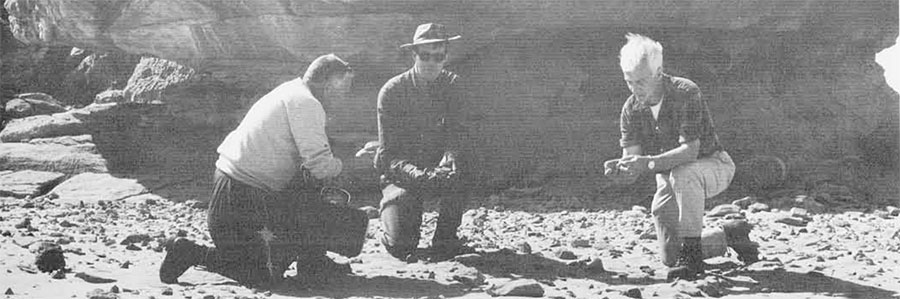

It had been decided that the mines lay off to the northwest and could be reached more easily by circling around through the desert. David stayed by the intercom in touch with Angelo while the rest of us searched for pottery, stone tools, and rock carvings. Artifacts, lying on the surface of the sand were most common in the shelter of huge rock outcrops and it was on the sheltered undersurface of overhanging rocks that we found rock engravings of cattle, gazelles, and other unrecognizable animals. They were faintly reminescent of palacolithic carvings in France and Spain, and yet distinct with a special character of their own. Most interesting to me were the many fiat grinding stones and the manor used in many regions in the Neolithic period for grinding grain. Our Applied Science Center has now dated the pottery, with the thermoluminescence method, at 6997 B.C. ± 420, but notes that it is possible that this pottery was not fired sufficiently and that therefore this date is erroneously early.

(Right) Dr. Ayoub and a friend before one of the typical houses in this oasis.

Our big disappointment came when Angelo and the Tibu returned unable to find Egi Zuma in that maze of wadis. Ayoub felt that the Tibu, a shy and diffident man, probably did know where it was but would not insist upon his opinion. However, at that point we could not delay for long in the search because Ambassador Newsom was due at Kufra on January 15 and we still had to cross the most difficult region of the Rebiana Sand Sea. All of us left the Tibesti with reluctance and a general desire to return at the first opportunity. We spoke of the beautiful natural landing field near the ‘Cathedral’ and how to organize a future search by air and on the ground, supplied by aircraft. The Tibesti is full of mysteries and Egi Zuma remains for me an objective.

As the Tibesti faded away in the west Jebel Baarsa loomed on the horizon to the east. Passing this rather gloomy and isolated range we turned north into the Rebiana Sand Sea which was to be our greatest challenge. An ancient caravan route from Chad and the Tibesti passed this way to the single well called Hassenofou, then the oasis of Rebiana and on north to the Mediterranean many weeks away. In the heat of summer the sand sea is practically impossible for vehicles because the sand is too soft, but in the cooler winter months it is more firm and just possible with the proper sand tires and a careful selection of the route. We were particularly worried about the trucks.

At our first camp on the edge of the sea Angelo stepped out of his Rover and picked up a palaeolithic handaxe. By that time the whole party had turned into archaeologists and they were soon scattered all about the camp making collections. Only in Nubia and at one place near Sebha have I seen anything quite like this. Scattered all over the desert were patches of chips and tools and other stones lying on the surface of the sand. Handaxes, blades, scrapers, projectile points, and endless retouched flakes and chips, mostly of palaeolithic age but also an occasional potsherd or grinding stone of the neolithic period. Bob Wells was so enthusiastic about this fantastic workshop that he and two or three others spent half the night roaming the desert with gasoline lanterns. Our departure next morning was delayed while the rest of us collected. We could not then imagine that for the next three hundred kilometers, right across the sand sea, we would seldom be out of sight of such scattered patches of stone tools.

For the next day and a half we worked our way across the sea with one or more vehicles stuck every hour or less. We hand pushed out the Rovers and waited for the trucks to work their way out with the metal sand tracks, but at every stop most of us scattered like birds searching for seeds. Hard stones, red, black, and yellow in color, which had been utilized by those ancient hunters, were now sand-blasted until they glistened in the sun like polished jewels. Why should millions upon millions of such artifacts now be lying on the surface of the desert as if they were abandoned only yesterday? Pesce thinks that sometime during the Ice Age this was a grassland or bush country with many lakes. Certainly it must have been rich in game during the Old Stone Age and still moist enough for cattle and grain in the post-glacial neolithic period. Drifting sand must now cover and uncover all those chipping stations and time has concentrated on one level tools which were made over a period of several hundred thousand years. Still, it is appalling to think of the number of people and the number of generations represented by that endless deposit of tools.

To Ayoub’s great relief we finally reached Rebiana, which is a picture-book oasis surrounded by the endless sand sea, checked in at the police post and then began to bargain with the Tibu. Gradually they brought out all their weapons (spears, daggers, and swords) which the police had been trying to confiscate. Those we did not buy were then grabbed by the police whose business it is to see that the Tibu stop fighting among themselves. All the weapons were made by ironworkers among the Tibu. Our caravan left absolutely bristling with spears. David and Rocky made their courtesy call on the chief of the Zawia and Kennie Dod set up a sort of moving clinic to examine the sick. He was fascinated with all the evidence of cupping.

Turning east again toward Kufra we were soon out of the worst of the sand sea, but just before climbing up onto the plateau, we halted to wait for the trucks and Bob Wells made his last search for artifacts. He called out with some excitement, and joining him I saw what was truly a Stone Age workshop. An outcropping of hard red stone had been used as a quarry, and lying all about were large chopping tools, long flake blades, and various scraping tools, together with masses of chips and flakes resulting from manufacture on the site. All of these surface collections in an area as remote and little known as the Rebiana Sand Sea are practically impossible to date, but comparing with other excavated material in North Africa I would guess that this particular workshop dates from the middle palaeolithic period which, on a worldwide basis, is estimated at some 50 to 150,000 years ago. A representative series from Bob’s collection is now in the University Museum.

Kufra is not what I expected. This remote oasis is now very much a part of the world today and, I hope, of the world tomorrow. The Occidental Oil Company is putting five percent of its net profits from Libyan Oil production into an agricultural experiment in the region of Kufra and in less than seven months has turned it into a dramatic example of what the Sahara can produce. Deep wells tap a reservoir of water, thought to be of pleistocene age, which is probably larger than all of the American Great Lakes. It has no salts and is absolutely pure except for a small quantity of carbon. In the traditional cultivated area (where there are ancient shallow wells) aluminum pipes and sprays are watering a whole new group of vegetables and grains, which is impressive. But the real surprise is the commercial farm out in the open desert ten kilometers from the ancient cultivated land. Here a great green field of grain and hay has sprung to life under the glistening water jets. There will soon be 1200 acres under cultivation. Then sheep will be brought in from the Sudan, fed at the farm, slaughtered there, and the meat shipped by air to Tripoli and other coastal towns. Five crops a year are expected. This is the miracle of water in the Sahara which thoughtful people have been discussing for years, and also the miracle of modem technology applied to the world’s most serious political problem—population growth and limited natural resources. It struck me that America’s most important export today is that kind of technology and the American farmers like Neal who train the Libyans to use it.

It was good to have a shower and a comfortable bed at Occidental’s experiment station (prefabricated steel houses which had been trucked in over the desert from the sea five or six days away) but even better to talk with the men who were changing the desert. Other guests were British Air Force pilots who had flown in spare parts for a British expedition stuck in the desert near Kufra.

Seven of us took off late the next day in two Land Rovers for a dash of some 350 kilometers south to Aweinat on the border of Libya, Egypt, and the Sudan. There is a police post in this range of mountains at a spring, welling up out of huge piles of granite boulders which made me feel like a Lilliputian. This is seven days by camel caravan from the nearest wells to the south and the north and thus absolutely critical for the caravans moving northward from Chad and the Sudan. We had passed one during the night and were to meet it again on the return the next day. Our objective was a series of rock paintings in wadis to the north and south of the spring which were known to our Tibu guide and the police.

Although I had seen illustrations of these particular paintings, the originals were surprising. Colors are often fresh and clear, black, red, white, and pink, and the figures are sophisticated in style and execution. For the most part animals represented are cattle, and obviously domesticated since you see them grouped around poles or stakes and corraled. But there are also other bovine animals and gazelles. There are many human figures, often with bows or spears and many with white anklets, all in a most distinctive style, again faintly reminescent of palaeolithic art. After the vast numbers of stone tools in the Rebiana Sand Sea we were surprised at the relatively few flint chips and potsherds on the desert around the spring and the rock paintings. A Belgian expedition is working in the area but we did not meet it.

The long way back to the coast at Marsa Brega was broken by frequent meetings with truck convoys roaring across the roadless desert with pipe, machine parts, food, and supplies of all kinds for the experiment station and the police at Kufra—huge vehicles with many wheels and broad tires adapted to this kind of sand sea navigation. We chose our own route skirting the Calanscio Sand Sea and often had our usual difficulties with soft sand so that there were many opportunities to search the surface for artifacts—none at all. The ancient lonely world of the desert ended about 200 kilometers from the coast with the first of the gas flares, black smoke, and oil derricks which mark one of the richest oil fields in the world.

Marsa Brega is now blocked off from the main coastal road by an army control point since a recent explosion, believed to be sabotage, destroyed a small part of the new refinery. When our fleet of Land Rovers and trucks arrived there in the darkness the guard challenged the Ambassador’s leading car. We were tired, thirsty, hungry, and eager for a bath in the oil company’s rest house. It is no wonder we were all restless and irritated by the long delay, particularly since the authorities had been warned by radio of the arrival of an official party. Later, in the American club, Rocky Suddarth raised a shout of laughter when he told us he had overheard one guard say to another, “If that’s the American Ambassador, I’m King Idris!”

There is no doubt that every man in our party would like to return to the Tibesti and the search for Egi Zuma. Most of them were chosen as David’s guests because they already knew the strange, harsh fascination of the lonely land, but this was a particularly happy trip, with no casualties of any kind. Some day I hope a University Museum expedition can fully explore the northern Tibesti with its base at the ‘Cathedral’.