to the left. Photo by David P. Silverman.

“I will tear the veils from every mystery: mysteries of religion or of nature, death, birth, the future, the past, cosmogony, and nothingness.”

Few mysteries fascinate humankind so deeply as that veil to which Rimbaud alludes: the gossamer barrier that separates “here” from “hereafter.” All cultures address questions of life after death in some fashion, with answers ranging from radical materialism and nihilism, to perpetual rebirth and its eventual cessation, to the polar dichotomy of Heaven and Hell. However, few possess a tradition of theological speculation on such matters that approaches the longevity of that of the ancient Egyptians. In Egypt, such beliefs and practices endured and evolved for more than 3,000 years, from the first religious texts composed in the 3rd millennium BCE, through the early centuries of the Common Era, when Christianity gradually supplanted traditional Egyptian religion. Further, many solutions regarding the puzzle of the afterlife, as framed in later Western traditions, find their earliest antecedents in the cosmologies of ancient Egypt. This article explores one aspect of this existential puzzle: the nature of the Damned, their punishment, and ultimate annihilation.

The Earliest Egyptian Religious Texts

Approximately 4,400 years ago—more than two millennia before the birth of Christ—Egypt had existed as a unified nation for nearly 700 years, and the Great Pyramid of Khufu at Giza was then more than two centuries old. At that time (ca. 2374 BCE), inside the humble pyramid of a certain king Unas, there appeared the earliest collection of Egyptian religious literature.

These “Pyramid Texts,” which were reserved initially for use in royal pyramids, but later adapted (after ca. 2100 BCE) for non-royal burials, represent the first known attempts by the Egyptians to describe their conceptions of the afterlife. However, the Pyramid Texts lack systematic descriptions or illustrations of the world beyond. Instead, they rely exclusively upon spells, hymns of praise, and lists of offerings to convey their message. In these contexts, the geography of the beyond was described mainly in terms of the sky, as home to the stars and domain of the sun god. The celestial region was envisioned as the surface of a winding waterway, upon which the gods sailed in great boats, a metaphor derived clearly from daily life on the Nile. Foremost among the cosmic deities was the sun itself, which the Egyptians called Re. The sun was believed to die each evening in the west, before descending into a hidden, nether sky known as Nun. The ensuing nocturnal voyage culminated in the sun’s rebirth from the Akhet, a zone of transition in the eastern heavens, separating yes- terday’s death from the new life of today. In the Pyramid Texts, this solar cycle served as one of the most important models for the salvation of the deceased king.

Through apotheosis, or divine transformation, the Pyramid Texts guaranteed the individual’s transcendence of physical mortality, asserting repeatedly: “You have not gone away dead, you have gone away alive!” the spells reinforced this affirmation through constant identification of the deceased king with Osiris, the god whose death and resurrection functioned as an additional template for salvation alongside the concept of solar rebirth. Ultimately, every part of the body was imbued through magic with the divine properties and immortality of Egypt’s most powerful gods. Thus, we understand the desired outcome of the Pyramid Texts—which is to say, salvation—as escape from the clutches of bodily death and transformation into a living god, with freedom to roam the cosmos unhindered, “according to this prerogative of his: If he desires, he acts; if not, he does not.”

But what of salvation’s dark twin? What horrors might await the unfortunate soul who fails to achieve apotheosis? The Egyptians virtually refused to entertain such thoughts with regard to their kings. Consequently, the Pyramid Texts are decidedly circumspect. Since the spells’ emphasis falls squarely upon successful deification, details regarding any alternative outcome must be teased out from fleeting and oblique allusions. When the spells assure us that the deceased individual is not, in fact, “dead” but “alive,” we may infer that the former state represents the antithesis of the hoped-for divine transformation. Further, spell 93 reveals that the beings, known collectively as “the Dead,” are possessed of “wrath” against those who have avoided their fate. In spell 524, they are trapped behind a “boundary,” which does not hinder their deified counterparts, who are directed, in spell 666B, to avoid the canals that lead to their abode, which is both “dangerous” and “painful.” Given these clues, it becomes clear that the “Dead” in such cases must connote some darker reality: Not merely death, but a terrible fate beyond death, which is to say, damnation.

Mortuary Spells that Guaranteed Divine Status

The Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom were inscribed almost exclusively below ground, in the tombs of kings and, by the end of the Sixth Dynasty (ca. 2206 BCE), queens. Comparable mortuary spells for private (non-royal) Egyptians are unknown from that early period. Consequently, belief in apotheosis for private individuals during the Old Kingdom remains an unproven hypothesis. Nevertheless, by the end of the First Intermediate Period (ca. 2190–2061 BCE) and into the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2061–1700 BCE), unambiguous textual evidence from private tomb walls and coffins—the so-called “Coffin Texts”—demonstrate clearly that any Egyptian with financial means could obtain spells guaranteeing his or her divine status after death.

These texts make clear that knowledge concerning the esoteric nomenclature of beings, structures, and locations in the divine world functioned as the magical key necessary to unlock the door to apotheosis. Thus, Coffin Text spell 1035 states: “As for one who knows this spell for going down into [the paths of the divine world], he himself is a god in the entourage of (the god) Thoth…but as for one who does not know this spell for traversing these paths, he shall be seized by the snare of the Dead.” Building upon the earlier Pyramid Text tradition, the deceased is identified now as an individual “god” among a larger divine company, whose status stands in contrast to the collective “Dead.” e text indicates the undesirable, which is to say damned, nature of the latter group through its description of their state as a “snare” (literally, a “net-thing”), which “seizes” the unfortunate souls, whose ignorance of the proper magical safeguards prevents their translation into the divine world.

The Fate of the Damned

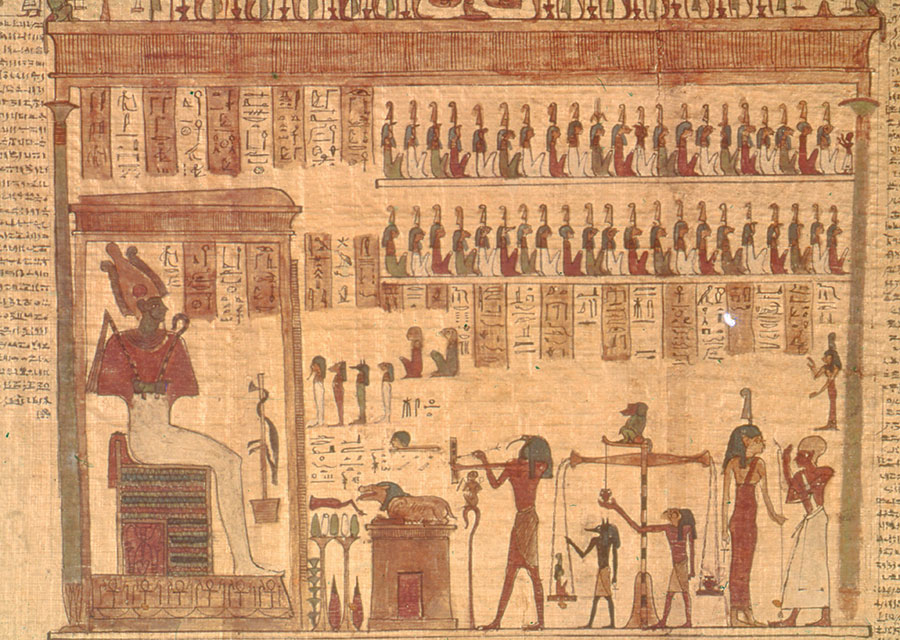

The trajectory of theological speculation attested in the Pyramid and Coffin Texts reaches its zenith in the New Kingdom (ca. 1569–1081 BCE). For the first time, we find elaborate, if not necessarily systematic, accounts of the Damned and their hellish fate, which is described and illustrated in exquisite, and often gruesome, detail. The most well known of these texts, the so-called “Books of the Dead”—which the Egyptians termed “Spells for Going Forth in Daylight”—provide us with the earliest, explicit representations of Divine Judgment. In spell 125, (see page 17) the deceased is led before the god of the dead, Osiris, and his divine tribunal in the “Hall of Two Truths.” There, a massive balance weighs the heart of the deceased against the principle of cosmic order, Ma’at. Success or failure at this critical moment hinged upon the individual’s relationship to this principle, which functioned something like a blue print for the correct functioning of the cosmos, as defined by the creator when the world was made. The jackal-god Anubis—assisted in some versions by the falcon-headed god Horus—tends the scale, while ibis-headed Thoth records the outcome. If the lifetime of the deceased contributed to the maintenance of order, the heart would strike a balance with Ma’at. A successful judgment came with the verdict “true of voice,” transmission into the blessed afterlife, and entry into the company of the gods. Ownership of a Book of the Dead effectively guaranteed this outcome. Nevertheless, the threat of failure was ever-present in the monster, “She-who-devours,” whose form combined at- tributes of Egypt’s most rapacious predators: the head of a crocodile, forequarters of a great cat, and hindquarters of a hippo. Should the heart fail to balance with Ma’at, the demon crouched nearby would be ready to consume the unfortunate soul, relegating him or her to the status of damnation. In this regard, She-who-devours provides a fortuitous antecedent to the medieval Christian motif known as the Hellmouth: a great beast whose jaws consume unrepentant sinners, transmitting their souls to fiery perdition.

The State of Damnation

For an Egyptian, failure to acquit one’s self in the Judgment removed forever the possibility of apotheosis and entry into the blessed afterlife. The resulting state of damnation received its most thorough account in a group of cosmological works known as the “Books of the Underworld.” In those works, the abode of the Damned appears as a place of fire, dismemberment, torture, and unimaginable suffering, similar in many respects to medieval conceptions of Christian Hell and its Islamic counterpart, Jahannam.

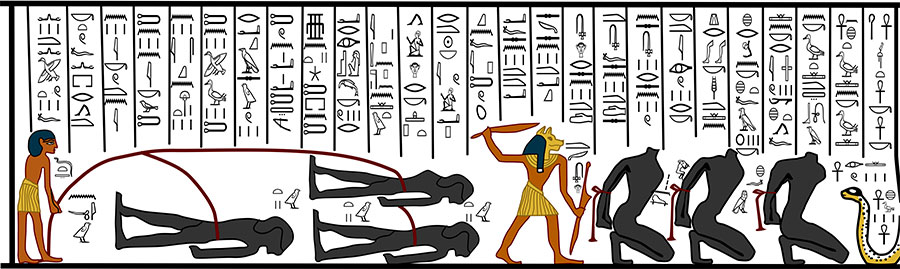

One of the earliest such representations appears in the seventh hour of the “Book of the Hidden Chamber,” also known as the Amduat (“What is in the Netherworld”): Two groups of damned souls are tortured before Osiris, in his capacity as ruler of the Underworld. The first group, “enemies of Osiris,” kneels before that god, their arms tied behind their backs. A cat-headed demon, “Violent-of-Face,” wielding a knife, has already severed their heads, erasing their individual identities. Behind this group, a second demon, called “Punisher,” restrains three additional prisoners with ropes, as they await their immanent slaughter. In the text, the sun god explains to Osiris: “Let your enemies fall beneath your feet…The flames of the Living Serpent are against them, that he might burn them. Violent-of-Face is against them, that he might cut them down and roast them on a spit for him- self.” Subsequent Underworld literature developed these themes to an ever more elaborate degree. Thus, in the fifth division of the “Book of Caverns,” we learn that the torture of the Damned was not limited to mere bodily mutilation. Within a fiery cauldron, hieroglyphic emblems designating “souls” and “shadows” are incinerated, along with scattered chunks of flesh.

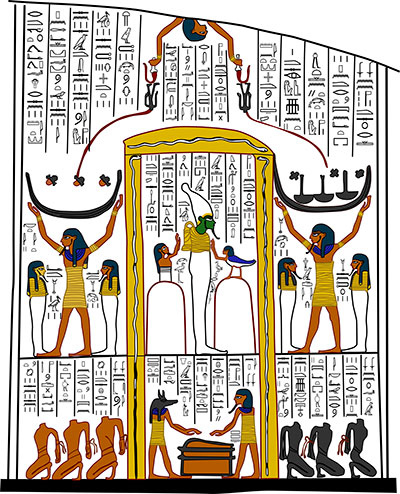

The Egyptian cosmos was believed to exist in delicate balance between the centripetal force of Ma’at, cosmic order, and a centrifugal counter-principle known as Isfet: entropy, or chaos. The punishment of the Damned, as agents and avatars of Isfet, was one aspect of this balance, which served to maintain the cosmos in perpetuity. However, Egyptian texts do not usually describe the torture of individual human souls as an ongoing or otherwise eternal process. Rather, their punishment was intended to produce a single, once-and-for-all destruction: a complete unmaking of the individual. Thus, in the second division of the Book of Caverns, the sun god proclaims: “O, you enemies…of Osiris, look: I have consigned you to annihilation, having condemned you to non-existence!” is same idea finds potent, visual expression in the “Book of the Earth”: Within the “Place of Annihilation”—the nearest Egyptian equivalent to Hell—Osiris presides over the final destruction of his enemies. Overhead, two blackened corpses hang inverted, alluding to one of the most disturbing indignities that the Damned must suffer: Reversing the natural order, they eat and drink through the anus, excreting urine and feces from the mouth. However, the time for that foul repast is over, for the enemies’ heads have been severed. Blood pours from their open necks, filling cauldrons in which their “corpses, souls, and limbs” are “incinerated.” The mechanism of this fiery destruction is the arrival of the sun god who, the text explains, passes overhead, “inflicting punishment” on the mutilated enemies. After the sun departs, the enemies are forced to “confront their darkness, which has no light.” Thus, consigned to oblivion beyond any possibility of salvation, the Damned—wretched agents of chaos—were excised like deadly cancer from the fabric of the cosmos.

The Egyptians conceived of punishment in the afterlife, and the resulting annihilation of the Damned, as a cosmic struggle beyond the pale of normal human experience. However, at their core, these beliefs reflected concerns of this world and a fundamentally human need to believe that wickedness will be rewarded in kind: if not in this life, then in the next. It was this need, coupled with a belief in some greater, cosmic framework of ethics and morality that ultimately outlived the traditional religion of ancient Egypt, to re-emerge in later conceptions of Hell as a place of punishment in diverse religious traditions throughout the Near East and Mediterranean.

JOSHUA AARON ROBERSON, PH.D., a Penn Museum Kolb Fellow, is Assistant Professor of Art History (Egyptology) at the Univer- sity of Memphis, Institute of Egyptian Art & Archaeology.

For Further Reading

Allen, James P. The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts. Atlanta: Society for Biblical Literature, Writings from the Ancient World, vol. 23, 2005.Hornung, Erik. The Egyptian Amduat: The Book of the Hidden Chamber, translated from the German by David Warburton, revised and edited by Erik Hornung and Theodor Abt. Living Human Heritage Publications, 2007.

Hornung, Erik. The Ancient Egyptian Books of the Afterlife, translated from the German by David Lorton. Ithaca and London: Cornell, 1999.

Quirke, Stephen. Going Out in Daylight – prt m hrw: The Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, Translation, Sources, Meanings. GHP Egyptology, 2013.

Ritner, Robert Kreich. The Mechanics of Ancient Egyptian Magical Practice, Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 54. Chicago: University Press, 2008, fourth printing, pp. 111–90. Available free online from the publisher, at http://oi.uchicago.edu/research/pubs/catalog/saoc/saoc54.html