World’s fairs—also called exhibitions, expositions, or more recently expos— have had a great impact on the development of museums as institutions since the inaugural world’s fair 160 years ago. The first recognized world’s fair, the 1851 Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations in London, was directly responsible for the creation of the Museum of Manufactures, later called the South Kensington Museum, and now known as the Victoria and Albert Museum. Incorporating exhibits from the 1851 Exhibition and an existing School of Design, which had been established in 1837, this museum-school model inspired a new era in museum development over the next several decades. The model’s impact on museum development in the United States, in particular, was exceptionally strong.

Americans who crossed the ocean to attend the 1851 Exhibition in London were deeply impressed by Europe’s marvelous museums and were embarrassed by the lack of such cultural establishments back home. They realized that art museums could be the public face of a city, representing cultural developments and artistic tastes. Also, like the British, Americans wanted their own design professionals to compete in the world market, so as to reduce importation of decorative art works. In 1870, New York and Boston established art museums: the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Both of these museums took the South Kensington Museum as its model as each incorporated or collaborated with an art school as part of their original plan.

The South Kensington Model

According to Malcolm Baker and his colleagues (1997), the South Kensington model became even more popular in the United States after the influential 1876 Centennial International Exhibition in Philadelphia. When the gates of the Centennial Exhibition closed, the doors of the Pennsylvania Museum (now the Philadelphia Museum of Art) and the School of Industrial Art (now part of the University of the Arts) were opened shortly after. e Connecticut Museum of Industrial Art was registered in New Haven. The Corcoran Gallery was expanded and became associated with a design school in Washington, D.C. The Cooper-Hewitt decorative arts program increased its collaboration with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. One of the most prominent of the new institutions was the Rhode Island School of Design and Museum, which was established in Providence in 1877. Through time, although some art schools became independent, many remained affiliated with or closely linked to local museums, and these museums and schools continue to influence decorative arts education in the U.S.

This is not to suggest, however, that world’s fairs resulted in the creation of only art or decorative arts museums. The Philadelphia Centennial facilitated the building of the National Museum, now known as the Arts and Industries Building at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. And the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago led to the establishment of several museums. The Chicago fair’s ethnographic, geological, mineral, and zoological exhibits became the core collection of the Columbian Museum of Chicago, now known as the Field Museum of Natural History, which was funded by the Chicago entrepreneur, Marshall Field.

The Philadelphia Commercial Museum

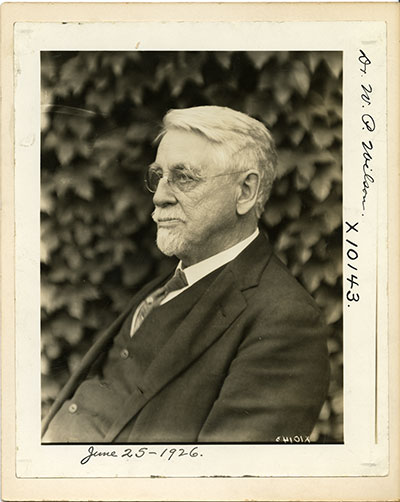

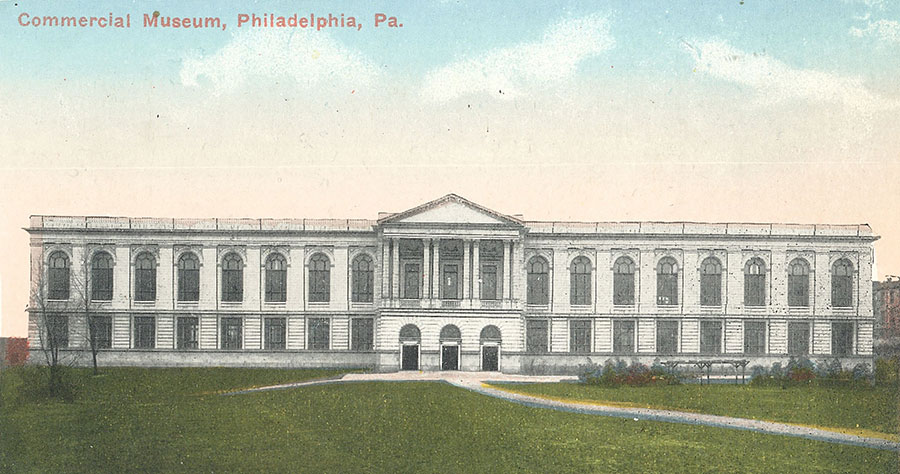

While the origins of the Field Museum are commonly known, few people are aware that the 1893 Columbian Exposition also prompted the creation of another special museum. This was the Philadelphia Commercial Museum, which was dedicated to commerce and international trade. In operation for about a century, the Museum contributed to a unique and glorious chapter in American history and museum development. Deeply impressed by the depth of the exhibits at the 1893 Columbian Exposition— which featured natural products of every sort and from every corner of the world— Dr. William P. Wilson (Commercial Museum Director, 1894–1927), a professor of botany at the University of Pennsylvania, saw value in making the exhibits permanent collections for education and foreign trade. After gaining support from the City of Philadelphia, Wilson procured 24 railroad carloads of natural products from the Chicago Exposition and expanded these holdings with materials from many other world’s fairs, such as 400 tons of material from the 1897 International Central American Exposition in Guatemala, 500 tons from the 1900 Paris Exposition, 15 carloads of material from the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, and 20 carloads from the St. Louis Exposition of 1904 (Hunter, 1962). According to Steven Conn (1998), citing other scholars, the Commercial Museum was considered the unofficial museum of world’s fairs— or even a permanent world’s fair— due to its eclectic collections.

Established in 1894, court documents state that the Commercial Museum’s mission was to “foster international trade by collecting and making available to the public for study cultural, trade, and economic materials and artifacts from all over the world.” The National Export Exposition and the International Commercial Congress, organized by the Commercial Museum and the Franklin Institute in 1899, brought the Commercial Museum onto the world stage. With the aim of bolstering America’s competitive standing in the global market- place, the Commercial Museum not only provided services in collecting and preserving raw and manufactured products, but also assisted American manufacturers in securing wider markets for their products and building desirable connections in foreign countries.

The Commercial Museum’s library was equipped with hundreds of publications on trade, commerce, and finance, as well as official statistics and reports from governments and commercial organizations throughout the world. Even foreign businessmen consulted the Commercial Museum’s library for information about doing business in the United States.

Educational outreach programs, aimed primarily at American school children, were also an important part of the Commercial Museum’s mission. Between 1900 and 1910, a total of 2,500 cabinets— containing 25 different drawers with miniature collections of raw materials— were sent to schools throughout the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

In 1912, the Bureau of Domestic and Foreign Commerce was established under the U.S. Department of Commerce. The rapid expansion of the Bureau’s role over the next decade assumed many of the responsibilities of the Commercial Museum. In the half-century that followed, the Commercial Museum shifted its focus to educational programs and public events. Ultimately, it struggled to survive. The Commercial Museum was closed to the public in 1981 and closed permanently in 1994. Per an Orphan’s Court order, what remained of the Commercial Museum’s standing collection was dispersed to local museums and cultural institutions in Philadelphia. The Penn Museum received more than 5,000 objects, mostly ethnographic and archaeological material from past world’s fairs, some of which are featured in this issue.

The relationship between world’s fairs and museums remains intact, although it has changed with time. World’s fairs are becoming more driven by cultural themes, with less of an emphasis on trade and physical objects. Though world’s fairs still provide inspiration for new museum creation, such as the Shanghai World Expo Museum, which was built following the 2010 Shanghai Expo, the modern world’s fair- inspired museum is often a historical or memorial museum, rather than a collection-oriented decorative arts or ethnographic museum, such as those that came after the early fairs. Although museums enjoy longer life than world’s fairs, even museums are not guaranteed to be permanent institutions, particularly when their mission is no longer valid, as was the fate of the Philadelphia Commercial Museum. However, the collections of the Commercial Museum live on at other institutions such as the Penn Museum, with many objects accessible to museumgoers and scholars.

XIUQIN ZHOU is Senior Registrar at the Penn Museum. Zhou has written books in Chinese on world’s fairs including History of World Expos and Expos and Museums.

For Further Reading

Conn, S. Museums and American Intellectual Life, 1876 –1926. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Hunter, R.H. The Trade and Convention Center of Philadelphia: Its Birth and Renascences. Philadelphia: Philadelphia Board of Trade and Conventions, 1962.

Orphans’ Court Division of the Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia County. Re: Civic Center Commercial Museum Collection Trust. e City of Philadelphia, Petitioner. ADM. No. 676 of 2001.