Near Eastern archaeologists generate compelling headlines and grab attention searching for lost kingdoms, temples, and palaces, but most everyone knows that modern archaeology encompasses far more than the pursuit of great discoveries. Archaeologists strive to reconstruct past cultures and study cultural evolution and human-environment interactions over time. Nevertheless, I confess that our new archaeological project in Iraqi Kurdistan provides the best of both worlds—the thrill of discovery coupled with the satisfaction of conducting long-term anthropological research. We established the Rowanduz Archaeological Program (RAP) in 2012 with the goal of producing a detailed understanding of the ancient cultures of the remote northeast corner of Iraq’s Erbil Province— the area of the modern towns of Rowanduz, Soran, and Sidekan— from the first agricultural settlers to the early modern period. We are also searching for a lost Iron Age kingdom that many scholars believe flourished here in the later 2nd and early 1st millennia BC before meeting a tragic end at the hands of the Assyrians.

Ancient Musasir

While RAP studies all time periods, the Late Bronze Age (1600–1200 BC) and early Iron Age (1200–330 BC) represent our main focus. is research interest grew out of my analysis and publication of aspects of the Penn Museum excavations at Hasanlu Tepe (1956–1977) in northwestern Iran. This famous early Iron Age site lies in the valley system just across the border from the RAP region, and the two areas exhibit similar cultural horizons. Many scholars believe that this archaeological culture in Iraqi Kurdistan formed the core of a kingdom called Musasir in contemporary Assyrian texts (see page 30). Hasanlu’s socio-political affiliations and ethno-linguistic composition remain unclear, and it constituted a separate kingdom. The great foes of the Assyrians, the formidable Urartians of eastern Turkey and the Caucasus, referred to Musasir as Ardini. Particularly important in this region were the mountain passes linking the highlands of northwestern Iran to the Assyrian plain, and both Assyria and Urartu sought to control them. The scenic Rowanduz Gorge is by far the most famous of these passes with incredible vistas, caves, and waterfalls.

The most compelling evidence that the RAP study area was Musasir comes from two stone stelae erected by Urartian kings at the high mountain pass of Kel-i Shin and near the modern village and stream bearing the name Topzawa. The stelae presumably lay along an ancient route linking Urartu to Assyria via Musasir and both inscriptions are concerned with the kingdom of Musasir and its ruler, king Urzana. Despite its neighbors’ political designs, Musasir maintained relative independence as a buffer state between Urartu and Assyria. In part, the region’s natural fortifications deterred invasion, but Musasir probably relied on divine protection as well. Musasir was home to the main temple of the god Haldi. The temple served as a transregional cult center, bestowing status and wealth on the little kingdom. Nevertheless, tragedy would eventually strike at the very heart of the realm.

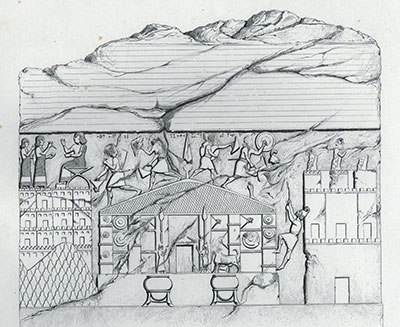

to ancient Assyrian depictions

of Musasir. The buildings were destroyed while still in use.

Sargon’s Eighth Campaign

city of Musasir by Sargon’s troops. Khorsabad, Palace of Sargon, Room XIII, slab 4. Botta, Monument de Ninive 2 pl. 141.

In 714 BC, the Neo-Assyrian king Sargon II conquered Musasir and sacked the Haldi temple at the end of his famous eighth campaign. The prevalent interpretation of Sargon’s route into Musasir maintains his army surprised the mountain stronghold by entering from the east via the Kel-i Shin pass, descending down into the Topzawa valley to Sidekan, and sacking large numbers of settlements and the temple and palace. Sargon commemorated this achievement in pictures and text on stone bas-reliefs found in his palace at Khorsabad, and in an incredible cuneiform text that enumerates the astounding wealth his soldiers looted from the temple and kingdom. The Assyrians forcibly resettled large numbers of Musasir’s inhabitants elsewhere and incorporated the region into their empire. Since we started RAP, the most common question we are asked is: “Have you found Musasir yet?” We have not definitively proven the RAP research area comprised Musasir, but after two seasons of fieldwork we have certainly unearthed compelling circumstantial evidence that we are on the right track.

While the area has provided few indigenous written records shedding light on the Bronze Age (3000–1200 BC) and early Iron Age (1200–330 BC), what little cuneiform exists from ancient Assyria and Urartu strongly suggests this area formed the core of Musasir or some other early Iron Age buffer state. Scholars have debated this identification since German researcher C.F. Lehmann- Haupt first advanced the theory in the early 20th century, but archaeologists have seldom had the chance to test his hypothesis through fieldwork. In the early 1970s, a German team led by Rainer Michael Boehmer conducted a few days of important preliminary research, revealing early Iron Age occupation centered on modern Sidekan. Boehmer even found stone column bases in the little hamlet of Mudjesir hinting an early Iron Age temple lay beneath its agricultural fields and orchards. After two seasons, RAP has added greatly to our picture of ancient settlement in the region.

a sequence of fortifications at the site.

RAP 2013-2014

The RAP research region contains diverse environmental zones ranging from precipitous gorges to high mountains and lush mountain valleys. We conduct research in all these areas to develop a complete profile of ancient lifeways. Today’s residents practice highly productive farming in the valleys—fruit trees and grapes are a regional specialty— and herd cattle, sheep, and goats in the highlands. Our botanical and zoological studies conducted by zooarchaeologist Dr. Tina Greenfield (University of Cambridge/University of Manitoba) and archaeobotanists Dr. Alexia Smith and Lucas Proctor (University of Connecticut) tentatively show similar patterns in antiquity as well as the hunting of diverse wild game up to the early modern era.

Since the RAP research region is virtually unex- plored, developing a regional chronology must be an immediate objective. To that end, RAP conducts excavations at the high mound of Gird-i Dasht located at the center of the Soran Plain. This multi-period mound represents the remains of several millennia of continuous occupation from at least 2000 BC to the early modern era. Kyra Kaercher (Penn Museum) and Melissa Sharp (University of Cambridge) are developing a ceramic chronology based on the Gird-i Dasht results combined with other RAP excavations and material from archaeological surveys conducted by Marshall Schurtz (University of Pennsylvania). Excavations on the high mound in 2013 and 2014, supervised by Dr. William Hafford (Penn Museum), Dr. John MacGinnis (University of Cambridge), and assisted by Anashya Srinivasan and Danny Breegi (Boston University) revealed a long sequence of successive fortifications consistent with the interpretation that the site served as a fortress controlling the plain and access to one of the main outlets to the Rowanduz Gorge. This site function continued up to the Ottoman period (19th century AD). Excavations on the low mound supervised by Dr. Richard Zettler and Katherine Burge (University of Pennsylvania) revealed some of the earliest periods of occupation at the site attested by painted and plain Khabur Ware ceramics of the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1600 BC). In 2014, a geomagnetic survey crew from Ludwig-Maximilians Universität headed by Dr. Jorg Fassbinder mapped large sections of the low mound, revealing the full extent of occupation and many interesting rectilinear anomalies that probably represent the outlines of buildings and streets.

Economic development can often run fast ahead of archaeology. In 2013, the Soran Department of Antiquities was alerted to the disturbance of a large number of archaeological sites—mostly cemeteries—caused by the widening of a road linking modern Sidekan to the Kel-i Shin Pass/Iranian border. In 2013, we conducted a survey along the long road cut and rescue excavations of a stone-built tomb of the late Achaemenid period at the site of Ghabrestan-i Topzawa. The tomb contained burials from two periods with over 20 individuals interred with ceramics, jewelry, and food offerings. Osteoarchaeologist Kathleen Downey (The Ohio State University) is studying the human remains from the tomb as well as other burials excavated by RAP.

Our survey of the road cut produced tantalizing evidence of several burned early Iron Age settlements near the original findspot of the Urartian Topzawa Stela that mentions Musasir. Radiocarbon dates from one of the largest burned sites, dubbed Gund-i Topzawa, indicate a construction date in the early 1st millennium BC. The pottery from this site suggests it was intentionally destroyed in the Iron III period, a date consistent with Sargon’s conquest of Musasir. In 2014, we excavated Gund-i Topzawa and Jorg Fassbinder’s team conducted geomagnetic surveys at early Iron Age sites in the surrounding area first documented by Rainer Michael Boehmer in the early 1970s.

Masasir Located?

Our excavations at Gund-i Topzawa revealed multiple stages of well-preserved masonry buildings terraced into a hillside overlooking the Topzawa Valley and River below. These excavations were supervised by Darren Ashby (University of Pennsylvania), Dr. Conrad Christian Piller (Ludwig-Maximilians Universität), and Dr. John MacGinnis (University of Cambridge) with the expert assistance of Hardy Maaß (Ludwig-Maximilians Universität), Daniel Patterson (University of Pennsylvania), and our capable government representative, Dlshad Mustapha. Our 2014 excavations focused on the lowest terrace of this building complex where we uncovered the well-preserved remains of kitchens and storage areas. The terraced architectural methods resemble depictions of Musasirian architecture on Sargon’s Khorsabad palace relief (see page 29). The excavated buildings were destroyed by fire while still in use based on the numbers of in situ ceramic vessels and other artifacts found. Our surveys show other sites along the Topzawa River were similarly destroyed at this time, compelling circumstantial evidence of Sargon’s campaign.

Jorg Fassbinder’s geomagnetic survey team likewise produced tantalizing results. At the hilltop early Iron Age fortress of Qalat Mudjesir, their mapping produced detailed plans of the underlying buildings. Even more exciting, in the village of Mudjesir the surveys produced signs of a monumental structure in the area where Boehmer and other archaeologists—key among them Kurdish archaeologists Dlshad Zamua and Abdulwahhab Suleiman— have tentatively located the Haldi temple based on scatters of early Iron Age pottery and stone column bases. Have we located the position of the Haldi temple? Only future excavation seasons will produce conclusive results, but we seem close to pinpointing the elusive kingdom of Musasir.

MICHAEL D. DANTI is Consulting Scholar at the Penn Museum and a Co-Director of the American Schools of Oriental Research Cultural Heritage Initiatives.