One day, perhaps late in March of the year A.D. 457, masons set the final stone in the wall they had built to seal off the tomb of their late ruler. It was a strong wall of limestone blocks, set firmly in lime mortar. The masons, probably no more than two in the narrow space at the foot of the steps cut into the soft bedrock, turned and climbed up the steps to the top of the shaft leading down to the freshly sealed tomb. They departed, leaving the filling of the shaft and the building of the temple to others.

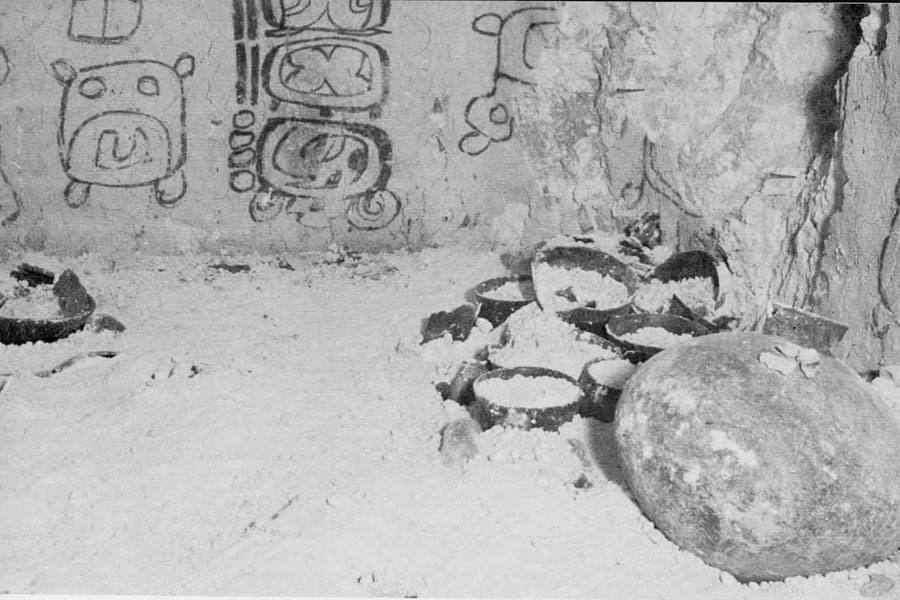

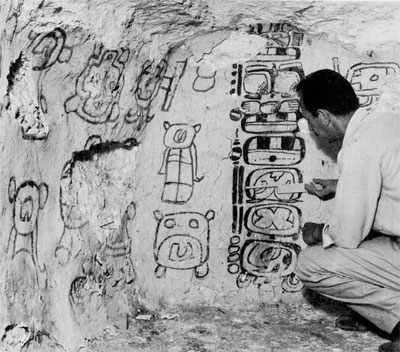

For several days they had worked inside the tomb, cut horizontally into the bedrock, plastering the walls and ceiling; as they worked, an artist, painting with a fibre brush, frescoed the large glyphs with bold strokes on the still wet, light gray plaster of the walls. Later they cleared the floor and brushed up the entrance way in preparation for the long and imposing funeral ceremonies befitting the high rank and importance of their dead ruler.

It is relatively easy to make deductions such as these about the masons from the physical evidence exposed by the Museum’s sixth expedition to Tikal early in 1961. The tomb, Burial 48 in our field notebooks and catalogue cards, had been tunneled into bedrock from the north face of a shaft penetrating the lower terrace of the North Acropolis. The rock-cut chamber lay on the axis of the North Acropolis directly beneath a succession of temples, the final one (Structure 5D-33) being in the middle of the row of temples facing south to the Great Plaza of Tikal. On one of the uniquely painted walls (unique as far as present knowledge of Maya tombs is concerned), there is a date, 9.1.1.10.10. in the Maya calendrical system, well into the Early Classic Period of Maya civilization, which corresponds to March 18, A.D. 457. The rich offerings in the tomb and two young teen-age skeletons, one on each side of the chamber as well as the important central position of the tomb itself, all bespeak the high rank and power of the deceased.

In a civilization as complex, and presumably as class conscious as that of Tikal, it is hardly likely that the masons who mixed the plaster and sealed the tomb were responsible for the frescoes, done with a sure touch that only complete familiarity with the hieroglyphic system could have developed. Such an artist may not have been a scholarly priest, but we are probably safe in inferring that he was a man of considerably higher degree than the masons and laborers who dug and later filled the shaft.

Beyond those rather simple, probably reasonably accurate, mental reconstructions of what went on both preceding and following the death of the principal occupant of the Painted Tomb, our inferences, based on the contents, are little more than guesswork. We have already decided that the general richness, compared to burials in simple graves, means high rank; a formal and perhaps lengthy funeral ceremony is, as we know from other civilizations, a usual accompaniment to burial and we do know from many depictions that Maya ceremonial life was rich with pageantry and elaborate symbolism. This is the basis of our assumption that a great ceremony took place, but beyond this there are only a few general aspects of the performance that warrant mentioning. In the first place, we are sure that the bones found in the center of the floor of the tomb are those of a man, fully adult, but, on account of the very bad condition of the bones and the lack of any part of the head, of uncertain age. This fact, coupled with the apparent, but not entirely conclusive, absence of the hands as well, makes the burial an unusual one. As a rule, the men of high rank buried in tombs in the region of Tikal were laid out at full length, and are found as complete skeletons. So, we are confronted with a headless and possible handless skeleton that was not laid out at full length, but which was found as a heap of rotted bones occupying a space that measured at most, two and a half feet in any direction. Some of the bones were in articulation, so we reason that the man was probably placed in the tomb in a seated position, from which the skeleton collapsed. Two major possibilities, but only possibilities, suggest themselves to account for his headlessness. One is that he lost his head (and perhaps his hands), in battle and that his mutilated corpse was recovered by his followers and brought back to Tikal for a funeral that would have pretty surely had military aspects, and at least overtones of revenge, thus differing from the obsequies held for a leader who died from natural causes.

The other possibility is that the man died without violence, and that his head, instead of becoming a trophy of his enemies,w as, on account of his enormous stature and spiritual power in the community, severed for preservation by his people. There are, of course, other alternative guesses, but that is all they are. This illustrates some of the limits and difficulties of archaeological interpretation. When we consider the nature of the funeral itself we are on much firmer ground for that part of it involving the actual furnishing of the tomb, but the thoughts and behavior of the participants, with the exception of some guesses, remain beyond our ken. It is clear that the excavation of the tomb in the rather soft bedrock could not be done without first penetrating the terrace floors of the North Acropolis and digging down to a level sufficiently deep to proceed horizontally into the north face of the rock. This vertical shaft was cut about seven feet deep and the tomb was tunneled out in the form of a rounded rectangle about nine feet long north-south, and five feet wide. The walls were widest apart at the floor, sloped inward, and were rounded off to the flat ceiling, and the whole interior except the floor was plastered and the walls frescoed. When this work was completed all was in readiness for the final ceremonies. We say “final” because it is quite likely that mourning and the preparation of offerings had been going on for some time. Surely there must have been a procession, perhaps along one or more of the great causeways that link the major temple areas of Tikal. We can imagine the body borne on a litter, priests in their plumed regalia, members of the family and retainers bearing offerings, and a band of musicians. If we can judge from the mural paintings at Bonampak in southern Mexico, which are several centuries later, their instruments may well have included drums, some form of trumpet, gourd rattles, and perhaps tortoise shells rasped by sticks, as well as whistles or ocarinas. There must also have been singing.

Along the avenues and in the Great Plaza a throng of onlookers must have watched the spectacle as the procession wended its way to the tomb. Whether the two young sacrificial victims destined to accompany their lord in his final resting place and into the next world were in the procession or waiting at the tomb, we have no way of telling. We are also in doubt as to whether they were stupefied by a drug or fermented drink, or fully conscious. From the positions in which they lay, one at each side of the tomb, it is clear that they were killed before they were placed in it.

Ceremonies prior to actual interment may have included more singing, perhaps dancing, and oratory in the form of eulogies. The exact procedure involved in finally placing the bodies in the tomb with the offerings can only be guessed at, but it seems likely that the headless body of the ruler was first carried into the tomb and placed in the center on cloths, a hide, or both. He was then probably covered with other rich cloths, which may have been the same as those that we believe were over the body as it was borne in procession. Cloth, and very likely a jaguar hide and feathers, had decomposed to form a thick layer of black rot; we could not distinguish the type of weaving and the floor had hardened sufficiently to leave no textile impressions of the kind that have appeared in a later tomb at Tikal.

The offerings were, we believe, then placed along both the end and side walls, right up to the body and in part ober it. On the east, the offerings consisted largely of beautifully burnished, smoothly incised pottery vessels, some of them with modelled lids. These had apparently been wrapped, rather than merely covered, with fine, open-weave cotton cloth, which left clear evidence in the form of fine grayish lines, of the rotted yarns on the black pottery. A cylindrical tripod vessel covered with a fine, eggshell thin stucco and painted was found on this side. This form of decoration is not uncommon at this time in the history of Tikal. There is good reason to suppose that this vase may have been imported from the highlands of Guatemala or even from Mexico, which would have made it an important and valuable offering.

Just to the right of the body, under the crushed skull of one of the youthful sacrifices, which had apparently fallen over onto it, stood a small, three-legged grindstone, deeply worn from much use. On it lay its handstone, ready for the preparation of corn in the hereafter. A large jar of plain, utility ware surely contained drink; we imagine maize beer. On the opposite, west, side a number of red ware bowls, some with tripod bases, contained food offerings. Most of these had also been wrapped in the same kind of fine, open-work textiles that had been used to wrap the black vessels.

We have not yet fully identified the skeletons of pigeon-sized birds that were found in one bowl covered by another, nor numerous large seeds of a tree. Several bowls contained brown or gray rot, probably the remains of prepared food, and on the floor the foot bones of deer seem to have symbolized venison.

The offering of food, drink, pottery vessels, and even of human victims, must have been considered virtual necessities for the after-life of the deceased. But, since he was one of the highest rank, his family and perhaps his associates in the hierarchy of priestly rulers felt bound to provide him with greater objects of value. Whether these had all belonged to him in life, or were contributed, is a question, but it seems likely that a considerable part of the most valuable furnishings had been worn or used by the headless man. The precious alabaster bowl with pale green stucco borders at rim and base, and a band of delicately incised glyphs is unique and must have been of great value. It was found among the black pottery near the east wall, and has suffered much deterioration from the dampness and contact with wall and floor. Originally it was an object of great beauty and the highest craftsmanship. Nothing comparable has been found in other Maya ruins.

One of the best criteria of wealth and rank in Maya society is the amount and quality of jade found in a person’s tomb. The headless man was accompanied by a great deal. Near the body lay hundreds of jade beads, the remains of a great semicircular collar embellished by jade discs. A tubular jade bead four inches long was found under the body. This is of very good quality dark green jade; it is unique in form. There were also two pairs of large earplug flares, the round ear ornaments that are depicted in sculpture being worn by Maya rulers and even by serpents and jaguars. A large number of jade beads singly or in groups of two or three were also offered. Possibly these were not the property of the dead man, but the contributions of individuals or groups.

Jade was so valuable in the lowland Maya region not only because it is handsome, but because it had to be imported and is very difficult to shape by hand with simple abrasives. Obsidian (volcanic glass) also had to be imported from the mountains. Two blades of this material, one of them a rare, greenish type, possible from Mexico, were found among the offerings.

The people of Tikal, although they lived at a considerable distance from the sea, were very much aware of maritime products and used them in profusion as offerings in caches and burials. In the Painted Tomb we expected to find a number of marine shells and stingray spines; we were not disappointed. No one can say what the religious significance of such marine products was, but they seem to have been felt to be necessary components of offerings for a long time during the Classic stage at Tikal.

When the last offerings had been placed in the tomb, and the masons had finished their work, the truly final phase of the funeral ceremony began. Again we imagine the priests in full regalia, mourners, music and singing and perhaps another procession. A fine new temple was erected over the tomb–a memorial to the late ruler or glorification of his successor? Afterwards, the tomb and its contents lay undisturbed in damp blackness until Shook looked in through a hole in the walled entrance fifteen hundred and four years later.

Aside from the presence of rare and unique objects among the offerings in the tomb, and the headless condition of its principal occupant, the painted walls themselves are of paramount interest. They are, with the exception of the Initial Series date, extraordinarily puzzling. The Initial Series is, in painted form, exactly the same kind of inscription that occurs on hundreds of carved stone stela in the Maya area. It differs stylistically from the glyphs on either side of it, which are much larger than those composing the date.

Among twenty-five separate glyphs, some repeated, there are seven that are wholly or in part recognizable to experts in Maya hieroglyphics, but in the context in which they appear in the tomb they are meaningless. This is not surprising when one realizes that all non-calendrical Maya texts have so far resisted translation. There has, of course, been much speculation as to the kinds of information they may have been intended to convey, for example, place names, people’s names and titles, in short texts. Some of the glyphs in the Painted Tomb may refer to places and people; it is even conceivable that if we could translate the whole text we might learn something of the condition under which the headless man lost both his life and his head. Since at least ten of the twenty-five glyphs are new–previously unrecorded–the tomb provides important new material on Maya epigraphy, but it will certainly be many years, if ever, before the full meaning of this remarkable inscription is known.