When the Center for the Analysis of Archaeological Materials (CAAM) offered its first classes in September 2014, the Teaching Specialists had a simple but potentially overwhelming task: to teach undergraduate students about research using the collections at the Penn Museum.

We had a single freshman seminar planned, a course called Food and Fire: Archaeology in the Laboratory. On the first day of class, laboratories were still waiting for furnishings and door hardware. In the four years since, hundreds of students have taken Food and Fire and other courses in CAAM classrooms and labs. Each student has had the chance to do original research on a Museum object or collection, with the help of eight CAAM Teach-ing Specialists.

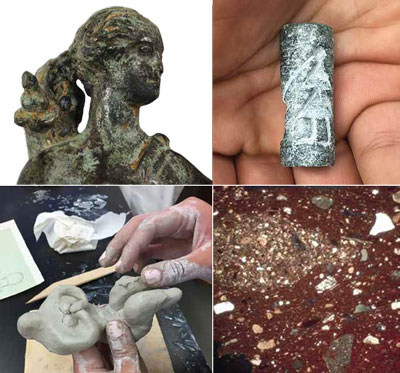

Students in Food and Fire take several different journeys. First, they travel in time from the remote past of human tool use to the present, making their own stone blades and using them to cut meat off animal bones. Second, they become familiar with handling Museum objects and using tools and instruments in the laboratory, working with the Teaching Specialists to understand key analytical techniques. Finally, they practice recording images, descriptions, and quantitative data, and communicating that data to Museum audiences using images and words.

Creating an Object Biography

(2020), and Wesley Wrubel (2021) with the author in the Collections Study Room;

Student research is organized using an object biography, a phrase coined over 30 years ago by Penn Museum Africa Curator Igor Kopytoff. For Kopytoff and the many mate-rial culture specialists who have utilized this concept, the biography of a material object is the comprehensive story of the object, encompassing who made it, used it, gave it away, and changed it in an accumulating set of meanings and stories. Each object in the Penn Museum has such a story, part of which is included in records in the Registrar’s Office and the Archives.

Students first become experts in using these records and then go deeper, studying raw materials used to make the objects, traces of manufacture, signs of wear and damage, and changes that have taken place since the object came to the Museum. They become knowledgeable about the archaeologists, collectors, and scholars whose work built the Museum, going as far as examining archival photographs of 19th-century drawing rooms to pick out objects later donated to the Museum. To understand the use-lives of objects, they make and use similar objects from the same materials and then map traces of wear under a microscope.

Students choose the objects from a curator-approved list and follow personal interests and responses as they work through the steps of the assignment. In the examples that follow, we can see how many different meanings the past has for today’s students and for the future of research on our collections in the 21st century.

A Bronze Mirror from Egypt

Ryan Kim (class of 2021) wrote the object biography of a bronze mirror from a tomb in the Upper Egyptian cemetery at Dendera. He studied a mounted sample from the mirror under the metallographic microscope with Teaching Specialist Moritz Jansen to find out about its manufacture and subsequent corrosion. Working with Assistant Archivist Eric Schnittke, he located the pages of archaeologist Clarence Fisher’s 1915 field notes describing this mirror and was able to reconstruct the original context of the object in the tomb. He found information on the analysis of the skeleton and records on a string of carnelian beads from the same wooden coffin. The most recent physical traces on the piece were repairs made years ago by retired Museum conservator Virginia Greene.

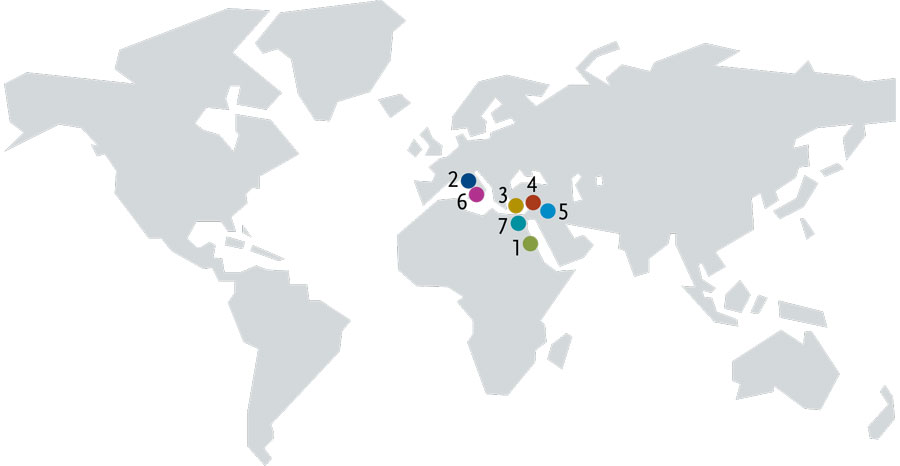

- Dendera, Egypt

- Tuscany, Italy

- Kourion, Cyprus

- Tepe Gawra, Iraq

- Surkh Dum, Iran

- Rome, Italy

- Tanis, Egypt

Sling Bullets in Warfare

Chris Colavita (class of 2017) studied a lead sling bullet from the Hermann Hilprecht collection of metal artifacts. The provenance of this piece is very general (Tuscany in Etruria), but the inscription and manufacturing traces were easy to see. Based on background reading for his paper, Chris became interested in the experience of using a sling bullet in warfare. He fashioned a modern bullet using lead weights from CAAM supplies and rigged a sling out of an old shirt. After some practice, he returned with a video of himself whacking the side of a garage with a solid hit. The modern bullet had flattened with the force of the hit, suggesting that the still-intact 300 BCE bullet had probably missed its target and been lost on the battlefield.

A Figurine from Greek Mythology

One of the most popular choices on the 2017 object list was a bronze figurine of Artemis from the Penn excavations at the Temple of Apollo at Kourion in Cyprus. Students such as Kelly Flynn (class of 2021) wore gloves in order to hold and study this object. Evangeline Williams (class of 2018) made several drawings and created a reconstruction of what the piece would have looked like before its arms and weapons were broken off. Williams wrote: “I chose this object because I was one of those kids who never got over their Greek mythology phase. I would spend hours memorizing the stories and drawing the family trees as well as the monsters who haunted them. Artemis was always my favorite; like me, she loved to be in the woods with her animals and always had her dogs by her side.” John Tsamoutalis (class of 2020) was determined to stitch together a 3-D image of the piece the way he had learned in Teaching Specialist Peter Cobb’s course Introduction to Digital Archaeology.

An 8,000-Year-Old Figure

Kathy Zhang (class of 2018) chose a female figurine from Tepe Gawra, Iraq for her project, making it the one of the oldest objects studied in 2017 (dated to ca. 6100 BCE). The modeled figurine seemed simple, but when she attempted to replicate its form she began to appreciate the artistry of the maker, especially in maintaining the rich curves of the legs while the piece dried. Another lesson emerged when the figurine was ready for the kiln in the Ceramics Laboratory. Teaching Specialist and CAAM Laboratory Coordinator Marie-Claude Boileau, Ph.D. warned her that many clay pieces do not survive firing. In fact, only a few minutes after the kiln reached temperature, a shattering blast sounded from inside the kiln, indicating failure. Many prehistoric figurines must have met a similar fate, indicating how special the surviving pieces would have been to their makers.

A Carved Seal from Surkh Dum

After his object study visits to Museum collections and a side trip to the Morgan Library in New York City, Aadir Khan (class of 2019) was inspired to portray a classic Near Eastern beer-drinking scene he had examined on a cylinder seal from Surkh Dum. The original piece is part of a cache of seals excavated in Iran by Erich Schmidt in 1938. Khan worked in steatite in the “wet lab” in CAAM, starting with modern metal tools and finishing his recreation with stone tools.

Zoe Belardo (class of 2021) replicated another part of the same design in her research. Her scale drawing of the seal made in the Collections Study Room accurately shows that the gazelle was added to the design upside down after the beer-drinking scene had been carved. She commented about the challenges of working on a mirror image of the final design in her assessment: “Carving itself requires a steady hand and thoughtful planning. Besides re-buffing the stone, there are few ways to erase erroneous carving; in general, once a mark is carved into stone it cannot be erased. Thus, seal carvers would have developed very high levels of precision to achieve their desired design.”

Ceramic Amphorae Handles

Mundane objects also have individual histories. Hundreds of thousands of almost identical ceramic shipping jars ended up in a single Roman dump during the period 100 CE to 300 CE. John Wanamaker, an early donor to the Museum, acquired 67 handles from these Mt. Testaccio amphorae. Students learned that the amphorae had been produced to carry oil from Spain. Consulting Scholar Gretchen Hall gave students a presentation on how to use infrared spectroscopy and other techniques to study the oil residue. In the Ceramics Lab, they used petrographic thin sections to see the composition of the clay used in one vessel, observing a blob of different clay that the hasty potter had failed to mix in. The handles also bear three-letter stamps pressed in when the clay was still wet.

Following the incidence of these stamps in scholarly publications allowed James Nycz (class of 2021) to visualize the entire ancient network of trade. His suggested object label read: “Stamped Amphorae Handle-Mons Testaceus, Southwest Rome. This object transported olive oil across the Mediterranean to a small port on the Tiber River in Rome, then was broken open and dis-carded on a nearby hill. The stamp ‘LQS’ indicates the amphora originated from southern Spain. Its contents being vital to Roman life—used in lamps, cleaning, or cooking—this type of amphora has been found as far as Germany and eastern Europe. These amphorae were the keystone of far-reaching Roman trade.”

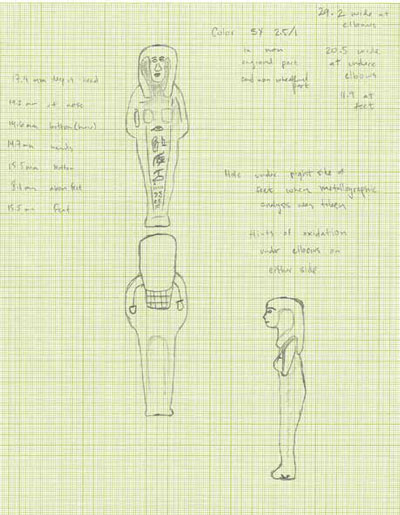

A Shawabti from Tanis in Egypt

Several students, including Daniel Salas (class of 2020), worked with a bronze shawabti, a figurine representing a funerary attendant from Tanis. They recorded its hieroglyphic inscription in the illustrations they made for their object biographies. Later, they worked with graduate student Paul Verhelst, who showed them the sound equivalencies for the different glyphs and the probable meaning of the glyphs on this piece. Being able to put a name to a face and tomb, to study the metallurgy associated with this piece, and to learn about beliefs regarding the Egyptian afterlife was a deeply engaging experience. Students were reminded that Indiana Jones visited the site of Tanis in Raiders of the Lost Ark. But the chance to study objects from the same place was a greater thrill.

KATHERINE MOORE, PH.D., is CAAM Mainwaring Teaching Specialist. She is also Practice Professor and Undergraduate Chair in the Department of Anthropology at Penn.

For Further Reading

Kopytoff, I. “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process.” In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. A. Appadurai, pp. 64–91. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.