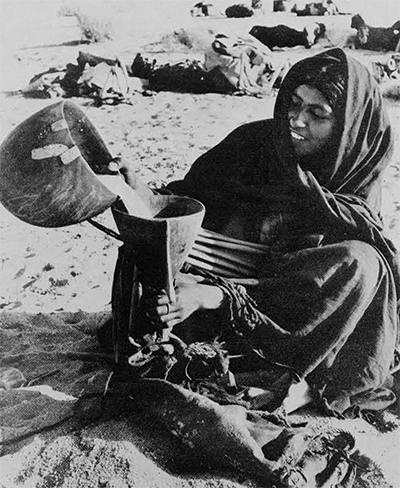

as the North African Tuareg shown here.

One of the great puzzles of cultural diffusion is why yoğurt, that greatest of all the gastronomic gifts of Allah, should have reached the English-speaking world under its Turkish name. It is true that the Turks spread themselves and their absolutely splendid cuisine across the Balkans even unto the gates of Vienna in the 16th and 17th centuries, but since their withdrawal from Europe their personal presence in this area has been very limited. Rather, it is the Armenians and the Lebanese who have founded colonies in virtually every city of the western world. Thus we should know yoğurt as madzoon, its Armenian name, or laban, its Arabic. In fact, the name Lebanon comes from this Arabic word meaning milk, as applied to the milk-white peaks of the perennially snow-clad Lebanon and anti-Lebanon.

According to San Francisco’s Armenian-American chef, Omar Khyam, emigrés from these countries, no matter where they go, do not want to do without their madzoon or laban and a last rite in their old homes is to dip a handkerchief into a bowl of it, let the handkerchief dry, and then pack it along with other household goods and chattels; the culture can be reactivated when they reach their new homes—alhamdillah! Praise be to God!

One wonders just how this works, inasmuch as many, if not most, of the Old World cultures are formed in goats’ or sheep’s milk, but will be reactivated in that of cows. One of these days I really must see what I can do with the ball of kishkh (hard, dry yoğurt cheese) given me by a basket boy on a dig in southeastern Jordan.

The ritual with the handkerchief (or some more conventional container) is necessitated by the fact that, in contrast to ordinary sour milk, which occurs spontaneously when milk has been fermented after being left for a time at modestly high temperatures, the bacteria causing laban must be artifically introduced into milk. So it is always necessary to keep a starter, sometimes called the rowbee, from one batch to the next.

Yoğurt or laban is the fermented, thick-curdled milk of camels, cattle, buffaloes, sheep or goats. It results when something like 80 percent of the milk sugar, or lactose, is turned into lactic acid by Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus. These are minute rod-like organisms, two to nine microns in length and one in width which multiply by breaking into halves, each of which then grows to the size of the parent in some 30 minutes; when the process is repeated. In this way, a container of laban will hold literally millions of these organisms in a very short time.

These bacteria grow well at temperatures between 77° and 113°F and die at a temperature over 140°. Other bacilli are usually present in laban and they, alone, or in combination, account for the distinctive flavors of the various yoğurt cultures, whether representing brand names or geographical areas.

Laban finds its home in hot, dry countries, many of which adhere to, or have adhered to, Islam. From the Levant, the yoğurt-laban complex runs up into the Balkans stopping dead at the Austro-Hungarian frontier, a fact which suggests that adverse historical factors barred its entry into parts of northern Europe. In fact, Austrian and north Italian cookery seem, not unnaturally, to have consciously rejected almost everything which might have come from the Turks, with only the use of coffee and the idea of strudel (née Arabic filo) rubbing off. Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica know laban, but Spain seems firmly set against it, possibly in reaction to long occupation by the Saracens.

The same sort of health food fad for yoğurt may exist in these European countries today as occurs in the U.S. I know this is happening in northern France. But this does not count in the distribution I am making here, which is to show the presence of laban in the timeless, traditional cuisine of these nations.

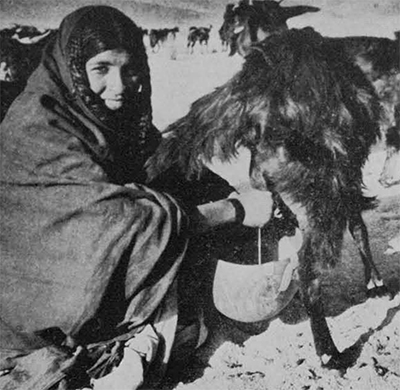

Laban is found all along the south coast of the Mediterranean. Then it runs southeast to and through India. It is known as mast in Persia and dahi in India and, in the latter country, seems to be used in practically everything. The fermented milk complex then continues into Mongolia and Tibet. In Mongolia, a related fermented milk appears as koumiss, fermented mares’ milk. In Tibet, yoğurt is made—in little pottery churns—from the milk of yaks by upland nomads whose main source of subsistence is their herds of these shaggy cattle. The use not only of yoğurt but of any milk at all must stop somewhere hereabouts, as many of the Far Eastern cultures, the old Chinese, for example, have a strong cultural aversion to the idea of the use of milk for human consumption, though cattle are kept for prestige and beef. As we will see, there is probably also a physiological basis for this attitude.

The Russians seem to be caught in a colossal pincers movement between laban and mast approaching from the Islamic south and the Mongol’s koumiss. With its great pastures, the Ukraine shows considerable emphasis on all forms of milks: sweet, sour, yoğurt, koumiss. Yet another fermented milk to be found in this general area is kefir, with a home in the Caucasus.

While the association of yoğurt with Islam undoubtedly has something to do with its absence in certain areas of Europe south of the Alps and Pyrenees, it must be to a large extent the climate north of this line which has been the determining factor in eliminating it from the traditional cuisine of northern Europe. As noted, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, the most important of the organisms which produce yoğurt, grows best at about 98°F., considerably higher than even the highest summer temperatures in this area, whereas the bacteria which produces normally sour milk flourishes at around 70°F.

Koumiss and kefir are yet another story. Kefir differs from the fermented milks of the Mediterranean in that it is started from a dried rather than a liquid parent—kefir grains. These are aggregates of Streptococcus lactis, S. cremoris, Leuconostoc dextranicum, Bacillus kefir and several yeasts, including Saccharomyces kefir. Kefir contains 0.5-1.0 percent of alcohol and enough carbondioxide to charge the drink, if tightly sealed while fermenting. Different tribes in the Caucasus have individual versions of it, with names like “hippe,” “kepi,” “khapon,” all, like kefir, deriving from a root which signifies “a nice taste.”

Kefir provides a large part of the diet of the mountaineers of the Caucasus, famous for their longevity, as well as considerable ability to put up a stiff resistance from their mountain refuge to absolutely anything they do not like. The kefir is most often prepared in goatskin bags or bottles; in summer, these are hung outdoors on a tree limb or, in winter, in the doorway of the house so that the heavy mixture of kefir “grains” forming in the skin bag will be broken up by agitation as people enter or leave the house. Fresh milk is added as kefir is consumed and the fermentation continues in the same bag ad infinitum. Not surprisingly, the mixture sometimes becomes a bit high. In contrast to yoğurt, kefir is a liquid, not a custard, and also contrasts with it in having a small percentage of alcohol.

In the valleys between the mountains, the villagers making kefir use open bowls rather than skin bags and so lose many of the gases formed from the lactose. The several organisms working together to produce kefir grow best at about 72°F; they die at about 95°F.

Koumiss comes From the great sweep of pastures of the central Eurasian steppes, once inhabited altogether by tent nomads, though those within the U.S.S.R. are rapidly becoming sedentary. Probably on the contiguous plains of the Ukraine, the horse was first domesticated, so the herds of these nomads are essentially of Equus, though including sheep and cattle as well. It is thus the milk of mares which provides the main item of the summer diet of these groups. This milk is never consumed fresh but always fermented into koumiss. Unlike yoğurt, koumiss is not started from the last batch, but from decaying animal or vegetable matter which contains the parent microbes. These produce a liquid combination of an acid and an alcoholic ferment.

Like kefir, koumiss is made in skin bottles hung in the doorway—of a circular felt yurt, or tent, this time—and again agitated by all who go in or out. Koumiss contains from 1.65 to 3.25 percent of alcohol when fully brewed. In the early part of the 20th century there was in this country a health-food fad for koumiss, though doubtless made from cows’ milk. The American brand used a formula calling for yeast, flour and honey to establish the ferment. To my surprise, I found a recipe for it in a 1912 Seattle Women’s Rights Cook Book, which had belonged to my mother.

Therapeutic claims have been made for most of these fermented milks, which to some extent must account for their appearance among the health foods-reform movements. The Russians at one point considered koumiss beneficial in treating tuberculosis and established sanatoria for the treatment. Great claims for both longevity and benefits to the digestive tract have been made for yoğurt, and currently the longevity of the peoples in the kefir area is under investigation, though in relation to coronary rather than digestive or lung troubles.

Yet it is absolute irony, and poor science as well, to claim that laban gives long life when it is a basic food all over the Near and Middle East and India where life continues to be shorter than anywhere else in the world. This claim was first made ca 1910 by the Russian scientist, Metchnikoff, who associated the high consumption of yoğurt in Bulgaria with statistics purporting to show that, of a population of about five million, some five thousand Bulgarians were centenarians. These figures can, however, point only to general illiteracy and an absence of birth certificates.

As to benefits to the digestive tract, a modest benefit may indeed occur, but it is on the principle of keeping black snakes in your garden to leave no ecological niche for the moccasins. The good bacteria of fermented milk will leave no room for bad ones. Quite recently, there have been claims for and studies made of what is believed to be extreme longevity in the Caucasus. Whether or not kefir is implicated here, it is another case of no birth certificates if we are talking of large numbers of centenarians. A few, I will accept (after all, two pharaohs, Rameses II in the 13th century B.C. and Pepi II, in the 24th, lived into their 90’s), but judging from the age of the general run of the skeletons we dig up, primitive life really is not all that conducive to longevity.

It is much easier to explain the absence of laban in the north of Europe than to be altogether certain as to why it is so popular south of the Mediterranean, especially since the milk must be heated to pasteurize it and start the bacterial action, and fuel is scarce hereabouts. Yet many Near Easterners refuse to touch sweet milk under any circumstances. This brings us to the topic of cultural selection of food. Why does one people eat one thing while another group absolutely refuses it?

As to yoğurt, through the pasteurization of the milk, it keeps better then unfermented milk in hot areas and does not become toxic since the milk sugar or lactose is turned into lactic acid. Yoğurt tastes better, too; further, on being thickened both by bacterial action and greater or lesser reduction of the milk by simmering, it is more satisfying than the thinner sweet milk. This might very well be a point in its favor in the food-short Near and Middle East. Nearer home, ask any dieter.

Over and above these reasons, the best explanation of the popularity of yoğurt and the other fermented milks would seem to be that their ease of digestion due to the conversion of lactose to lactic acid may counteract local subracial milk intolerances.

While many of us have been taught that milk is the gastronomic summum bonum, scientists in the past decade or so have shown that this is true mainly for those of (North) European descent and that from 80-99 percent of the Far Eastern peoples (depending on which immediate group you are examining) cannot tolerate it. Much the same percentage of African Negroes (again depending on the immediate group) are made quite sick by consuming milk. Figures for U.S. Blacks—in whom a certain amount of white European blood now flows—show only about a 70 percent intolerance.

Tolerance or intolerance to milk in turn depends on the individual’s production of the enzyme lactase which is needed to digest the lactose of sweet milk. Obviously northern Europeans are well supplied with this enzyme (though even so, 10-20 percent of adult white Americans lack it) while Mongols and Blacks lack lactase in the proportions noted above.

As American Blacks have a noticeably higher milk tolerance than their collateral relatives still in West Africa, it may follow that the tolerant gene is dominant and may have appeared with a mutation among milk-producing white groups sometime during the past ten thousand years, inasmuch as adults of no other mammal are milk tolerant.

The steppe Mongolians with their koumiss must fall somewhere between the completely milk-intolerant Chinese and the tolerant Caucasians; in fact, the two races shade into one another at just about the place where these nomads are found. One of the problems one can see coming up with the Vietnam refugees is their unavoidable reaction to the quantities of milk well-meaning social workers will give them.

Since the current yoğurt fad began, several studies have been made of its various functions. One of the more depressing comes from Johns Hopkins University to the effect that rats fed exclusively on commercially made yoğurt develop cataracts after one to six months of this diet. Humans, however, would have to eat about a third of their own weight in yoğurt per day before this would happen to them.

On a more cheerful note is the fact that yoğurt has been shown by London University investigators to reduce peak blood alcohol levels by 67 percent if ten ounces of yoğurt are consumed before drinking. Thai is to say, so much yoğurt has an effect on alcohol similar to that of a substantial meal, but leaves considerably more space for the alcohol.

At this stage of archaeological knowledge we really cannot say how far back into time the practice of milking and the obviously slightly later practices of making laban, koumiss, kefir, butter and buttermilk go. I would suspect laban to be the eldest, as its nuclear area corresponds to that of the earliest Neolithic (or agricultural) stage of culture in the European-Western Asiatic condominium.

However, it is the antiquity of koumiss which is best documented. This is firmly associated with the nomads of Mongolia and the Pontic steppe. We find Homer referring to “proud mare milkers,” almost certainly meaning the Scyths, though it is hard to see how they became the enfants terribles of all time on no more than 3.25 percent of alcohol, rampaging over the entire Near East in the 7th century B.C., let alone besieging Askalon for 28 years as Herodotus tells us. Very elegant koumiss dispensers made by Greek craftsmen are found in the Scythian tombs of the 4th century B.C. in the Ukraine, so ornate as to suggest a great importance attached to the brew.

Koumiss was known to Xenophon as well as to Herodotus; Pliny Secundus in the reign of Nero maintained that the really Grade A koumiss came only from the skins carried by the wildest horses. It reached its ultimate fame with Marco Polo and Ghengis Khan in the 13th century A.D. The former compared it to a good white wine. In keeping with the Mongol tradition that both the horse and the drink were given to man by the gods, the Mongol emperor is said to have retained 10,000 milk-white mares for the exclusive use of himself and progeny. All these references, however, belong to the historic period and to a late point within it.

We do not know just when and where laban first appeared, but it should have invented itself not long after man first thought of taking animal milk for his own use and let pots of milk stand long enough for the bacteria to settle in and do their work. How better to interpret such an event than as a gift from the gods? The animals were at hand and it is just a question of when the bright idea occurred to man. There is some slight evidence to suggest that this might even have antedated domestication, as the contemporary Bushmen of South Africa (culturally still in the Old or Middle Stone Age) are described as drinking from the teat of a female just felled, and there are other instances of this practice in the literature.

Which animals, once domesticated, were milked is also an interesting point. Most of them are, somewhere. The dog and the cat are excepted, as is the pig. The former are probably too small to make their milk yield worth bothering with. The main reason for the pig’s only sporadic appearance as a domesticant from the Neolithic onward (as well as the ultimate taboo against it spread through the Near and Middle East by Islam) is probably due to the fact that the pig is an inefficient machine at turning grass into food easily digested by man. But the difficulty of clearing so many spigots may account for its non-appearance among dairy animals anywhere in the world.

In any case, milking almost certainly began much closer to 9,000 B.C. (when domestication begins) than to 2,500 B.C. which is the approximate date of the temple at Ubaid, near the Sumerian city of Ur, not far from the head of the Persian Gulf, whose frescoes of milking are usually given as the earliest positive evidence of the practice.

Curiously enough, in spite of the importance of milk and milk products for the Sumerians, suggested by this frieze, milk is but rarely mentioned in any Sumerian text, including the 100,000 tablets from Drehem which deal with all other phases of the cattle-processing industry. Since the Sumerians wrote absolutely everything down on their clay tablets, it seems likely that they would have discussed milk, cheese and yoğurt—if they used the last-mentioned. That no tablets doing so have been discovered must be archaeological accident which we can hope to have remedied when documents on this subject turn up.

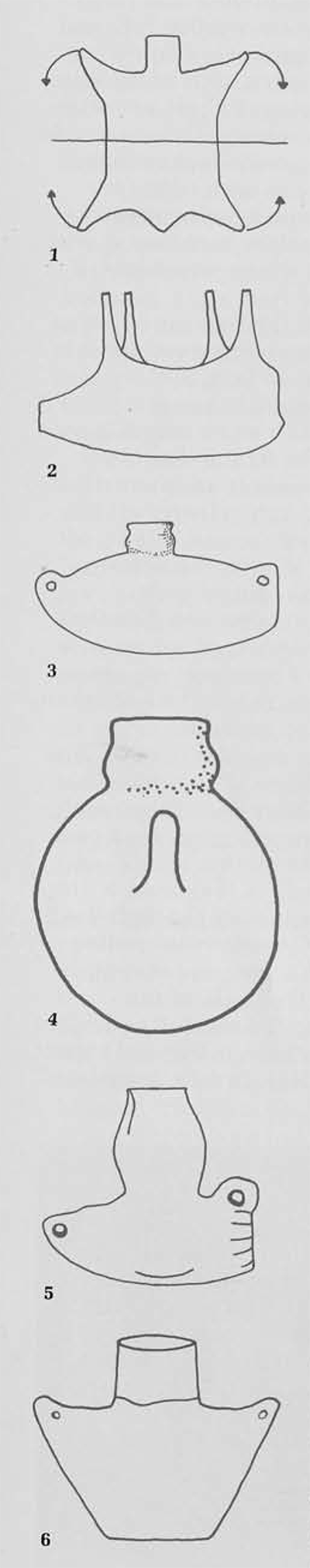

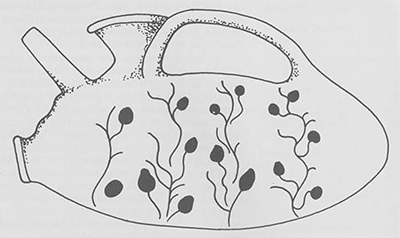

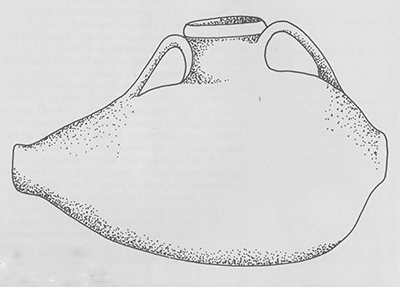

If pottery churns from the Palestinian Chalcolithic Beersheba culture are indeed churns—and less ancient as well as modern parallels suggest that this is certainly so—the date of butter making, hence milking, can be put back by another 1,500 years or so. A thorough survey of pottery retained in museums but never published might produce more and earlier churns, suggesting a starting date for milking much earlier than the 4,000 B.C. given for the Beersheba culture.

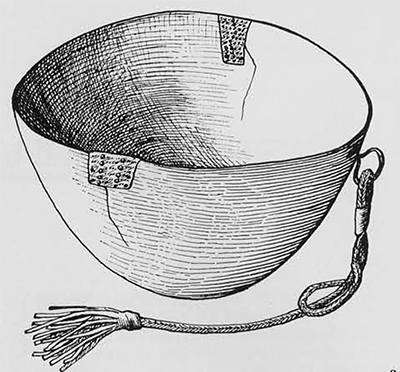

The Beersheba churns are asymmetric and seem to imitate the asymmetric shape of the goatskin containers originally used to hold milk (and still used in Mongolia and the Caucasus for koumiss or kefir production), one of which unwittingly became the first churn. This sort of copy in a new material of an object formerly made in different materials surfaces from time to time on digs of the most varied periods. There seems to be no continuity of imitation from period to period insofar as these churns are concerned, and modern ones imitate the skin bag directly just as clearly as do the ancient ones.

In this connection, we may ask why copy in clay something as awkward as a goatskin bottle? Well, new materials often copy older ones until the best shape for the new medium evolves; as pottery at first followed basketry; glass, pottery; and modern plastic now follows practically everything but has not yet found its own shapes. Further, one never knows what real or imaginary merit may have been assigned to the original shape by its earliest users. A real advantage to the pottery churn may have been that butter came more rapidly when the porosity of the ceramic cooled the milk and its firm walls speeded the granulation of the butter particles.

Nor can we say more precisely where laban originated than when. Ubaid and Palestine are in the right places, however, as the earliest domestication in the Old World nuclear area occurred somewhere in the arc of hills which hinges on Armenia, running through Kurdistan into Western Persia and southward again into Syro-Palestine. It will be a long, long time and a great many baskets of earth will have been moved by reluctant basket boys, however, before archaeology is able to pin down these origins precisely. At present, each discovery of the earliest agriculture seems to contain built-in evidence of even earlier origins somewhere offstage. What we are really getting at the moment is an impressive documentation of how much cleverer our rather remote ancestors were than we have been willing to give them credit for.

A great many peoples have claimed yoğurt as their own invention. The Bulgarians are one. The Turks are another. It is by no means impossible that the Armenian area of Turkey is also home to laban, but the latter must have appeared millennia before the Turks themselves came sweeping down out of the Asiatic steppes in the 8th and 9th centuries A.D. And this takes us back to the connection of laban with lactase deficiency as the Turks, at the moment they appeared in Anatolia, were preeminently Mongolian, though they have since, of course, added many Caucasian genes.

In this case, the Armenian madzoon may take us back a further stage, but the IndoEuropean-speaking Armenians could not have reached this area before 2,000 B.C. and may have come a thousand years later. Though the Neo-Babylonian texts of the latter part of the first millennium B.C. do not often speak of milk or milk products, the namasu sa sizbi, a pot for curdling milk, is mentioned. This might very well have been used for yoğurt making, but without further description of its uses we cannot be sure that it was not ordinary sour milk which was made in this vessel.

This leaves us with the Semitic laban as possibly the earliest surviving word for this form of fermented milk. In fadt, the city of Aleppo, not yet in Armenia, but well toward it in the north of Syria, has a name which is only an anglicanization of the Arabic halib, yet another term for milk. This is an interesting point, but we are going quite clearly off the stage of written history here and it is by no means sure how early, if ever, the Semites reached as far northeast of Arabia as Armenia. Very possibly, some non-Semitic, non-Indo-European and unrecorded peoples hereabouts who spoke a language we cannot even guess at are the real originators of laban, whatever they may have called it.

When the Israelites reached Canaan, one form of the milk and honey with which that land overflowed must have been Iaban and honey. Lamb or kid simmering in laban must have been the “kid in its mother’s milk” of which the Hebrew prophets took such a dim view, no doubt less because of the dish itself than because of other Canaanite iniquities.

A form of this dish survives today in laban immu (literally, the “milk of his mother”) which is found in Lebanon and Syria and thereabouts, just where you would expect it on the basis of the Bible. In fact, translated into mansif, this is the Arab national dish. I remember having it once on the feast of the birthday of Muhammad down in Jordan’s famous Wadi Rumm. My hosts were the men of the police post there—a dear little toy fort utterly lost in the awe-inspiring “Rumm of the thousand pillars.” In the open courtyard formed by the foresquare enceinte, the men of the police pounded up the dried kiskh and added it to the water in which a freshly killed kid was to be stewed. This gives the characteristic sour taste to the sauce or shurbah. While the mansif bubbled, we were entertained with music on a rubaba, or one-stringed violin, and, of course, with many little glasses of syrupy sweet mint tea, shai bi na’na’ . Wallah! But it was good!

Since the bacteria responsible for various yoğurt cultures vary, the yoğurts also vary and a yoğurt connoisseur will find a trip through the Near East absolutely fascinating. The best laban I have tasted to date came from a hotel at Antakya, ancient Antioch, on the north Syrian coast. Driving out to Jerusalem for an autumn dig, a friend and I stopped for a plate of this at some impossible hour, like 10:30 a.m., because we couldn’t bypass it even though it spoiled our timetable and spoiled our lunches, too. This Antiocene laban was so thick as to be almost cheese and had a beautiful sour tang.

Driving on toward the Holy City, with the yoğurt tang still alive on our taste buds, we were conscious once again of the “everlasting past.” How many generations of bacteria had left their mark on that particular yoğurt culture? Man makes food; food makes man. Wars migrations, cataclysmic ecospasms—all touch a swaying goatskin in the sun. We are the inheritors. “Al hamdu 1i illah rabbi ‘alameen.” Praise be to God the Lord of the beings of the whole world.”