“Never…have I seen so many stone vases in so short a time.”

Richard Seager, letter to Edith Hall from Pseira, 24 May 1907

Like a great many islands in other periods of history, the small Minoan islet of Pseira seems to have depended on its harbor and trade relations to compensate for poor land, few natural resources, and a hungry population. Pseira is only about 2 kilometers long. It is located just off the coast of northeast Crete, at the eastern end of the Gulf of Mirabello (Fig. 2). The Bronze Age town, set around the island’s most protected cove, was a prosperous village with over BO buildings at its greatest size. Imports of pottery and other goods show that it had far-flung trading connections at the time it was destroyed in Late Minoan IB (about 1550 or 1450 B.C. depending on one’s choice of high or low chronologies for the Minoan period). In order to add its own products to the trading network, Pseira seems to have developed a series of local manufacturing traditions. Among the most interesting of the local products was an attractive selection of stone vases.

The use and manufacture of vessels in stone began in Crete in Early Minoan II (the middle of the 3rd millennium B.C.). From the beginning, the motivation may have been more aesthetic than practical; with a few notable exceptions, such as lamps, stone containers offered few advantages over their counterparts in clay, and they were much more time-consuming to produce. Worked carefully by hand using abrasion techniques rather than carving, a vase could require many hours of drilling, rubbing, and polishing before it was completed.

In Pseira, a taste for stone vases was already present by Early Minoan II, the middle phase of the Early Bronze Age in Crete. Tombs in the Pseiran cemetery from this period contain fine examples of the stone-worker’s art. Most Pseiran tombs were small by Minoan standards. Measuring less than three meters across, and often less than two meters, they were used for dozens of burials over a period of centuries. Perhaps they were used by families. Only a few objects were buried with the dead, but stone vases were regular offerings.

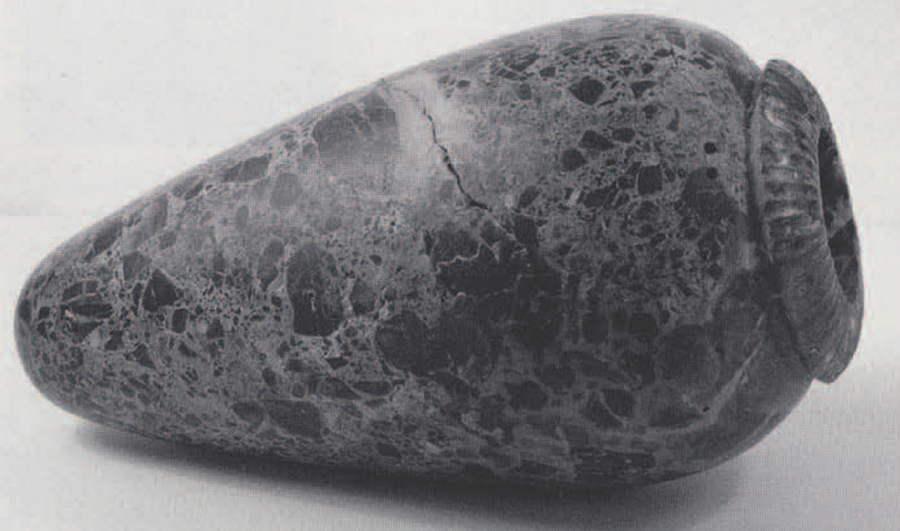

A burial illustrated here (Fig. 1) is part of a small house-tomb in the Pseiran cemetery. Beside the fragments of bones is a small vase called a bird’s nest bowl because of its resemblance to a small nest. Made of mottled dark green and pale green serpentine, bird’s nest bowls were common offerings in the Pseiran cemetery. They were given tightly fitting lids, with vase and lid usually made as a set out of the same material. The interiors are small, and the walls are rather thick, making a stable, heavy vessel. Unfortunately, no deposits have been found in the interior of vases that might give clues to the contents. The most likely theory for the vessels’ use is that they contained perfumed unguents, thick oils prepared with scents to anoint the body and offer protection against the hot Mediterranean sun as modern suntan creams do. Bird’s nest bowls are found in the town as well as the cemetery, so they were objects of everyday use in addition to being offerings to accompany the deceased into the next life.

The industry expanded in the Middle Bronze Age. It is possible that vases were already being produced locally by the Early Bronze Age, but certainly there were already local products by Middle Minoan times. Shapes were now more varied, and walls were thinner and more finely formed. The small cup in Figure 3 is an example from the Middle Bronze Age. Attractive open bowls, closed containers in several designs, and even vases with complicated spouts were made on a regular basis. The Minoans developed several typical vase shapes, especially for pottery, and these were sometimes imitated in stone. Other vessels were designed exclusively as products in stone.

The height of the stone vase tradition at Pseira, both in quantity of vases and in skill of manufacturing, was in Late Minoan I. It is difficult to be sure how many of the Late Minoan I vases were actually made on the island, but certainly many of them were local products. Among the stone vessels found at Pseira are some of the more attractive products of the stone-worker’s craft.

The recent excavations have contributed substantial evidence for the lapidary industry at this period. Besides dozens of examples of the finished products, the site has yielded unworked pieces of raw material up to boulder size, fragments of emery used in drilling, cylindrical stone cores formed inside the drills during drilling, and several broken and discarded pieces from unsuccessful vases. As a result, the industry can be traced from raw material through manufacturing to the use of the final products.

A wide variety of materials were used by the Pseiran stone workers, but all were relatively soft. So far, no evidence has appeared for the working of the quartz family of stones except for miniature objects, and it seems likely that stones with a hardness above six on the Mohs’ scale—like the quartz crystal vases occasionally found at other sites in the Aegean—were seldom if ever used on Pseira. By far the most favored material was serpentine. The Pseirans were fortunate that a large deposit of compact material existed just east of the modern village of Mochlos, within easy reach of Pseira by small boat. The serpentine occurs in a large formation in a ravine that extends down to the sea to a small beach, easily accessible by sea. The color of the serpentine from this outcrop is mottled gray to dark green, exactly matching the color of both finished vases and blocks of unworked stone found at the Minoan town.

Other materials, including several serpentines different from that of Mochios, are also found among the Pseiran vases. The material called serpentine is a family of minerals, not a single substance, and it almost always occurs with many impurities, so the color can vary widely. Colors at Pseira extend from gray to green to black to brown, usually with some variegation even if the material is solid and compact. Probably several sources were exploited for raw material, and occasional finished products from other Minoan towns were probably imported for their contents or for other reasons, making for a complex archaeological record.

Some of the raw materials were brought in from distant areas. Finds of small waste pieces of white-spotted obsidian from the island of Ghyale, in the Dodecanese, show that this exotic material was occasionally made into objects at Pseira. Obsidian from Ghyale is one of the few materials for which scientific analysis has confirmed that only a single geological source was exploited in the ancient Aegean. For most of the materials used at Pseira, either no scientific provenance work has been done yet or the results have not been conclusive. Finished vases have been found at Pseira of marble breccia, white and gray banded marble, brown limestone, red limestone, snowy white calcite, banded white and golden brown travertine, aeolian sandstone, and chlorite schist. Of these stones, only chlorite schist, red and brown limestones, and sandstone have been found as raw materials, but it is likely that all these stones were worked at Pseira because many of the finished products appear to be related stylistically.

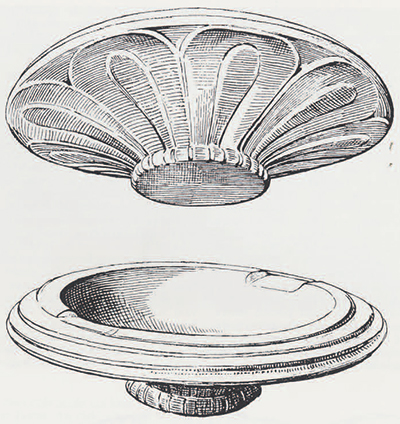

The inventory of shapes expanded lamps often had tall pedestals, but even lamps with low bases needed to be as stable as possible to avoid the danger of tipping and causing a fire. A heavy material like stone had obvious advantages. The lamp in Figure 6 was found in the Plateia House, a large building at the north of the town square at Pseira. Made of mottled dark and pale green serpentine, it is well smoothed and carefully finished. It had been used on the second story of the building, in a large room that was paved with stone slabs. Other finds from the upper room included cooking pots and charcoal bits, suggesting a kitchen area, and loom weights, suggesting an area for weaving. The lamp would have provided light for activities carried on in the upper story.

Among the more striking materials used for the vases was a compact, dark red limestone. Although the material is not native to Pseira, it was used for a number of objects at the site. Two lamps carved from this material are among the most attractive of the Pseira vases. One example is extremely flat, with a wide, shallow oil reservoir (Fig. 7). The lower part is carved with the petals of a lotus flower. The second red limestone lamp is taller, with a slightly higher base (Fig. 8). It, too, has carved floral ornament, a band of leaves on the upper shoulder. Both of the vases date to Late Minoan I.

The Platela House seems to have been a center for stone working in Late Minoan I. A large number of broken fragments from stone vases were in and near the structure, along with debris from manufacturing and greatly in Late Minoan I, the time when the Pseiran town reached its greatest size. Although utilitarian vases continued to be used in large numbers, they were now joined by several unusual shapes that might have been used in rituals or other ceremonies. Goblets on graceful pedestals (Fig. 4), large open basins, and rhyta are often regarded as religious vessels among the Minoans. A rhyton is a characteristic Minoan vase. Made with a small hole in the base so that liquid would flow out continually, it occurs in a variety of different shapes. An example from Pseira is shown in Figure 5. This vessel has a tall oval shape, with a small mouth and a tiny hole at the base; it could not stand without support, and it might have been designed only for carrying and holding or pouring, as it would not sit on a flat surface and no stands for the vessel occur in the archaeological record. The material of this example, an attractive red and black marble breccia, is known from several smaller vases found at Pseira. In contrast with this unusual shape whose purpose is not really agreed upon, some stone vases were strictly utilitarian. Among this latter class are the lamps. Stone was particularly well suited for the manufacture of lamps because of its weight. Minoan lamps burned fat or olive oil, substances that give only a little illumination, so most lamps had two wicks placed across from one another to provide more light. The wicks would soak up oil from a reservoir, and lighting them would cause the oil to burn, giving off light. In order to raise the light in the room above floor or table level, Minoan Archaeological Work at Pseira sity Museum by the Cretan authorities at the conclusion of the excavations. New archaeological work began in 1985 and is still continuing today under the direction of the writer and Costis Davaras. The new Pseira has been excavated in two periods. The first excavations are sponsored by Temple University, the two campaigns, in 1906 and 1907, were directed by Archaeological Society of Crete, and the Archaeologist Richard Seager and were sponsored by the American cal Institute of Crete. Substantial new information has Exploration Society, a private organization with ties to been discovered in the new campaigns, and an imporThe University Museum. Seager uncovered more than tant observation of Seager’s has been confirmed: 40 houses and opened 33 graves in the nearby ceme- Pseira was a center of the stone vase industry in Crete, tery. Many objects from his excavations, including a and its residents used stone vessels in many materials number of stone vases, were presented to The Univer- and in a wide variety of shapes.

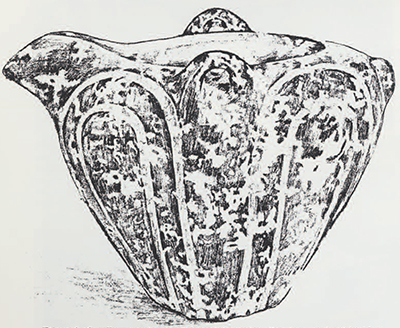

A few complete pieces. In terms of style and manufacturing skill, the nicest of the complete vases is a small spouted jar (Fig. 9). Like the red limestone lamps, it is decorated with carved petals. The jar was found in one of the ground floor rooms where it had fallen and broken at the spout and rim. Its shape, with two small handles at the rim and a tiny spout, is unique: petals enclose the small jar’s body as if the entire shape were intended as the blossom. The material is mottled serpentine.

The Plateia House is the largest building known from Minoan Pseiran (Fig. 10). It extended across the northern side of the Town Square, in Greek called a plateau, and one room extended south along the eastern side of the square. Its entrance, at the plateau’s northeast corners, was shaded by a small portico where stone benches sat. The importance of the structure is indicated by its impressive architecture, with a facade of large squared blocks across the northern side of the square, as well as by its decoration which included painted plaster (small bits with red and blue color were found in the modern excavations).

One of the most important aspects of the building is the evidence it provides for manufacturing. Besides the obsidian tool making and food preparation one might expect from any Minoan household, the Plateia House also provides evidence for weaving (loom weights), the working of triton shells (a complete example and many fragments), the working of quartz crystals (over 20 crystals and a complete pendant), and the making of stone vases.

In the Plateia House the evidence for stone vase manufacture included finished vases, materials that could have been used in their manufacture, and debris discarded from stone vase making. The evidence came from occupation debris scattered through several rooms, so that a specific workshop could not be isolated. Over 20 whole and frag mentary stone vases were found in the building itself, and other pieces were in debris from its collapse into the adjoining streets and platela. A drill core, formed inside a tubular drill during the drilling process, was also found in the building. Materials that might have been used in the manufacturing process, like pumice and emery, are also found at Pseira, although there is no way to prove that a particular piece was used in the making of stone vessels.

The vase industry of Minoan Pseira can be completely reconstructed. From the types of raw material found, it appears the Pseirans preferred to pick up rounded pieces of attractive stone from a stream or beach in preference to quarrying their material from outcrops. Some of the rounded pieces brought to the town were fairly large, while others were hand-sized specimens. Perhaps the workers felt that by careful selection they could choose a piece of raw material that was near the size of the intended product, saving time in the working of the stone.

The first step was a general working of the external shape. This stage will have revealed cracks or other flaws before the time-consuming process of drilling the interior. The top was then flattened, and the interior was drilled. The flattened top, necessary so the drill could begin with a good purchase, shows up clearly on the cores discarded after drilling.

The Aegean drilling system was similar to the process used in Egypt. The drill was a hollow reed that was turned with a rotary motion. The cutting was accomplished not by the drill itself but by a powdered abrasive whose tiny particles would catch in the end of the drill and wear away the stone. As the drill moved lower into the stone, a drill core would be created inside the hollow drill, to be broken and thrown away when the cavity was as deep as was desired. Fragments of emery have been found at Pseiran, and powdered emery, with a hardness second only to diamond, would have made an excellent cutting powder.

After the interior was complete, the vase could be finished. Early vases show rotary marks inside them from the drills, but by the Middle Bronze Age the interiors were carefully smoothed. Vases were completed by polishing, bringing out the pattern of the stone and producing a smooth final surface. A material like pumice would be very useful in polishing vases, and one wonders if some of the over 50 pieces found in the Plateia House were destined for this use.

Pseiran vases were probably traded widely. It is hard to identify most of the sources for Cretan stone vase manufacture because individual workshops are difficult to classify in ways that would distinguish the products of one town from those of another. A twin to the rhyton of red and black breccia was found at Knossos, and it is tempting to suppose that it was imported there from Pseira because Pseira is near the source of the raw material, and several other breccia vases are known from the island. So many vases from Pseira have carved petals on their exterior surfaces that one wonders if some of the vases found with this careful decoration from other sites might not have originated at Pseira. An elaborate cup with a rim spout and a strap handle at right angles to the spout, decorated with nicks and horizontal grooves, is known only from three Pseiran examples, one from nearby Gournia, and a fifth piece exported to Kea in the Cyclades, a certain Cretan export. Pseira seems the most likely source for this distinctive group (Fig. 3).

Perhaps the lapidary industry helped to compensate for the absence of clay on Pseira where pottery was probably never made locally (neither good clay nor an abundance of fuel for ceramic kilns was ever available on the island). Because large amounts of pottery were used on a daily basis, and it all had to be imported, one must suppose the Pseirans needed local products to exchange, plus at least a few locally made containers to act as substitutes. As one solution, the Pseirans turned to an alternative material, with the result that they created a lively tradition of interesting, attractive, and useful containers.