Urbanism was an essential element in ancient Egyptian culture, for its predominantly rural society was held together, and its extraordinary organizational, artistic and technological developments made possible, by a network of provincial towns dominated by two or three national capitals and sub-capitals. In terms of their historical functions and their archaeological remains, both the provincial and national centers would be described as ‘urban’ by historians and archaeologists. Egyptological archaeologists during the late 19th and earlier 20th centuries frequently encountered and sometimes partially excavated remains which they unhesitatingly described as ‘towns’ but when archaeological activity diminished from the 1930’s to early 1950’s the concept developed that Egypt was a “civilization without cities.” Now however, the importance of urbanism and urban archaeology in Egypt is being restressed, and a number of town sites are being excavated. Some are of the ‘classic’ long-lived type, with overlying strata and building levels covering many centuries. Others represent but a short time-span, but compensate for their lack of time-depth by preserving a basic town lay-out unencumbered by the overlying remains of subsequent centuries.

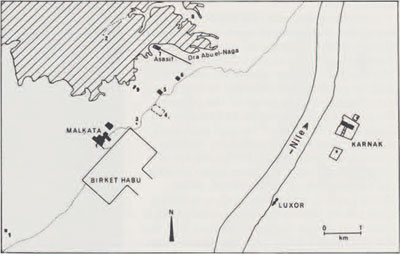

The most famous example of a ‘short-lived’ site is Tell el Amarna, the city founded by Akhenaten (ca. 1379-1362 B.C.) and largely abandoned within a few decades of his death. Less well known is another royal town, perhaps of a less strongly defined urban character but nevertheless of great interest, founded by Akhenaten’s father, Amenhotep III (ca. 1417-1379 B.C.) at Malkata on the west bank opposite the ancient southern capital of Thebes. Malkata had fallen into disuse within a century. It was partially explored by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (1910-1920), but the University Museum resumed excavations there in 1971 because several major questions remained unanswered. Five seasons of work were carried out (1971-1977), directed by the writer and Barry Kemp of Cambridge University, England; funds were provided by the University Museum and—primarily —grants of United States government funds from the Smithsonian Institution. Detailed publication of the results is underway and several fascicles have appeared or are in press, so far generously published without subsidy by the English publishers, Aris and Phillips.

A major question was: what was the nature of this royal town? The Metropolitan Museum had revealed the outlines of an Amun temple, several royal palaces, adjacent elite villas and traces of a workers’ village. Other excavators had found fragments of houses, contemporary with the ‘palace-city’ as it has been called, under later structures at Medinet Habu and behind the funerary temple of Amenhotep III’s favorite official, Amenhotep son of Hapu. These suggested that some form of urban development may have stretched from the palace-city to the funerary temple of Amenhotep III, now completely denuded but once the largest of the royal temples fronting the Theban necropolis.

Our investigations were necessarily limited, for the site of Malkata and its environs is very large (occupying just under two square kilometers, if the harbor is excluded) and some of our work was in waterlogged soil. However, we have shown that the palace-city continues under the cultivated fields which now intrude on much of the site; that a contemporary occupation level lay under Qasr el Agooz, near Medinet Habu; and other contemporary structures lay immediately northeast of the harbor. A magnetometer survey (by Beth Ralph, for MASCA), followed by selective excavation, also showed that the workers’ village was much larger than had been thought. Therefore, while the denser urban build-up of Amarna may not have occurred at Malkata and an extension to the funerary temple was not determined, the town remains were shown to be substantially larger than the original Metropolitan Museum excavations indicated.

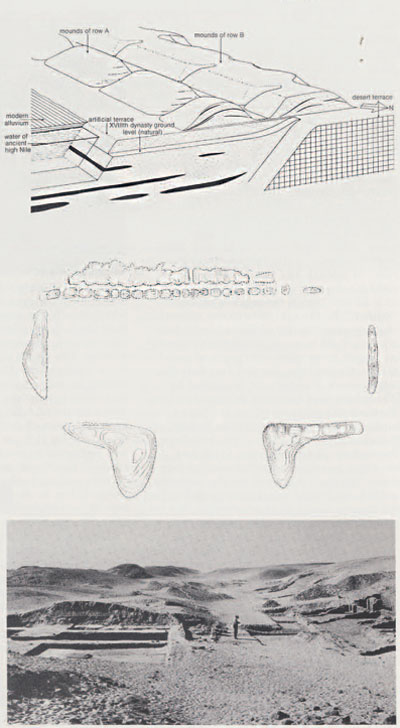

(middle) The mounds defining the shape and size of the harbor.

(bottom) View of the harbor mounds.

Our other principal target was a great harbor (originally probably about one and a half square kilometers in area) which lay southeast of the palace-city. The harbor’s location is still marked by enormous heaps of sandy soil thrown up when it was cut into the alluvial plain, although the basin has long silted up and is covered by modern fields; a canal once linked it to the Nile, well over two kilometers away. The Metropolitan Museum had not investigated this extraordinary feature. Texts refer to harbors as important adjuncts to Egyptian towns but that of Malkata is the only one (apart from a much smaller example in Nubia) to have been located.

We have demonstrated that the harbor was dug contemporaneously with the building of the palace-city (a fact sometimes assumed but not previously proved) and was an integral part of the over-all design. It consisted apparently of a simple basin without stone revetments, and the northwestern spoil heaps—partly fronting the palace-city–had been deliberately and regularly ‘landscaped’ for aesthetic or symbolic reasons. The harbor, fed by Nile water, would have functioned effectively for about half the year and no doubt was significant for the building and servicing of the palace-city. Its enormous size, however, is disproportionate, and contemporary texts make it clear that this vast expanse of water was also symbolic, a material expression of the mythology of kingship, and that the traversing of it by the king and queen was charged with ritual significance.

Our work has also increased knowledge of the prehistoric and historic geology of the region, detected prehistoric remains, and demonstrated considerable activity in some parts of the site (not the palace-city proper) in Hellenistic and Roman times. It has also added to our knowledge of Egypto-Aegean relations in the 14th century B.C. In 1977 we dredged up from the water-table, under three meters of stratified Hellenistic and Roman town remains, many late Dynasty XVIII sherds, including one Mycenaean example. A number of Mycenaean sherds were found at Amarna, but this is the first recorded at Malkata.