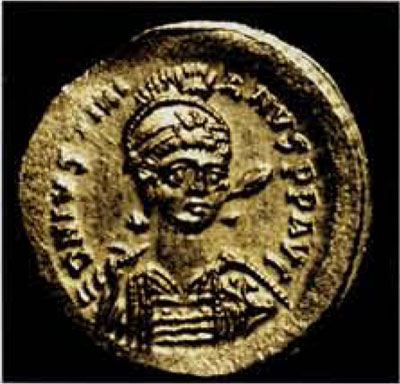

Byzantine Collection, Dumbarton Oaks, Washington D.C, 48.17.1384

What survives in Greek of Alexander’s writings consists of the Treatise on Fevers (in seven sections), the Letter on Intestinal Worms (the first tract on parasitology worthy of the label), and the Twelve Books, which address various ailments and their treatments. Except in excerpts, no English translations exist of the writings of this physician extraordinaire. There are, however, translations into German by Theodor Puschmann (1878-1879), and into French by F. Brunet (1933-1937) (see box on Translations of Alexander of Tralles).

Alexander practiced in the era of Justinian I (527-565) and his consort the Empress Theodora (527-548) (Figs. 1 and 2). Brunet’s bubbling admiration for Alexander of Tralles inspired him to assume that Alexander had to have been personal physician to Justinian and had to have had a role in the important actions of the day. (Brunet envisioned Alexander accompanying Justinian’s distinguished general, Belisarius, as physician in the Gothic Wars, for example.) Even though one can document that Alexander must have traveled and collected materia medico throughout Armenia, Thrace, much of the Balkan peninsula, Egypt, Gaul, Spain, North Africa, and Italy, there is no specific evidence to suggest any relationship with the royal family or participation in the wars waged by Justinian to restore the Roman Empire in the West. Brunet is easily forgiven, however, for his overreaching enthusiasm: after all, Alexander of Tralles was the best physician in the Byzantine Empire, so that a presumption of royal connections can well be understood, even if left in the realm of historical fiction.

Translations of Alexander of Tralles

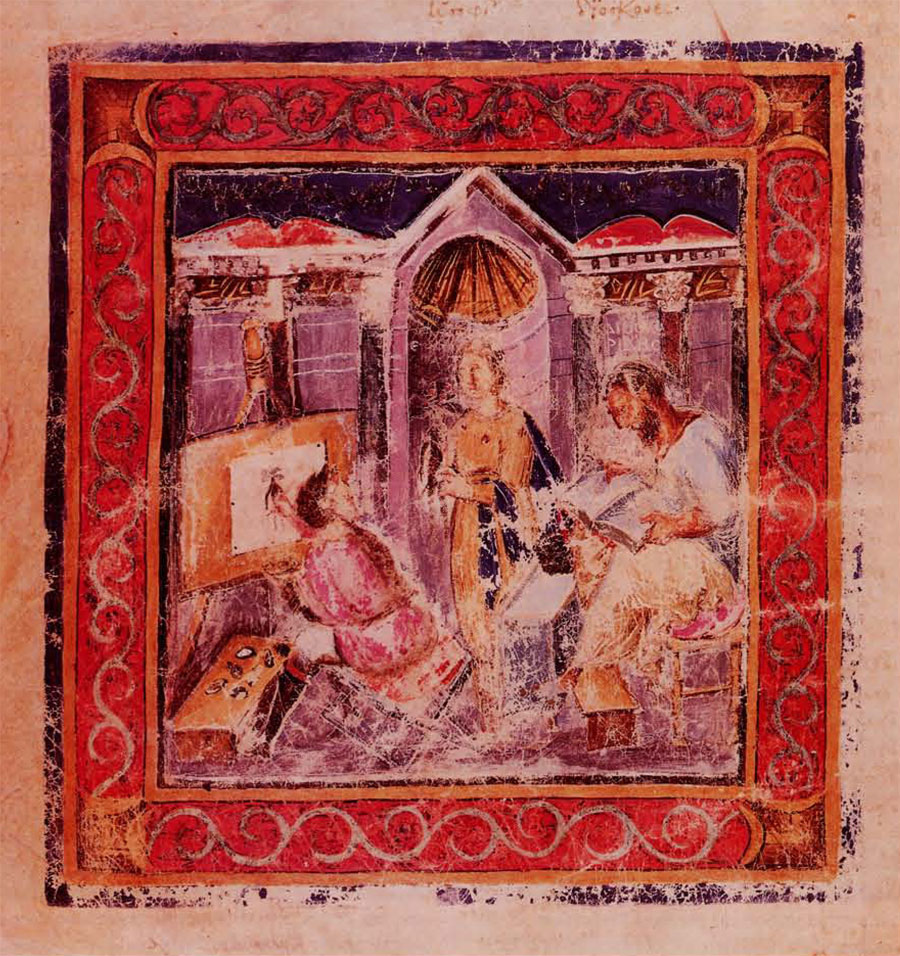

Christlich-archaologisches Seminar, universitat Bonn

Alexander’s writings were well known and respected by later Muslim doctors and pharmacists. The manuscript traditions are chiefly Greek, but also late Latin and Arabic. A complete re-editing of the Greek texts with an excellent German translation and running commentary was published by the talented physician Theodor Puschmann in 1878-1879, and this text remains standard in the analysis of Alexander’s medicine, surgery, and especially pharmacology. Puschmann’s opus also includes the most complete index to date of the drugs and pharmaceuticals listed and discussed throughout these writings. Of course, one must recall that Puschmann chemical and pharmacological synopses reflect the best research of the late 19th century, so that the phytochemistry and pharmacognosy in the commentary and index of plants, animal products, and minerals emerge from the finest German investigation of his time, not ours.

F. Brunet, a doctor in the French navy, claimed to have translated Alexander’s works into French directly from manuscript sources available at the time (1933-1937) in Paris. Brunet devoted his first volume to a generally undocumented but enthusiastic overview of Byzantine medicine in the age of Justinian. With little acknowledgment of Puschmann’s pioneering edition, Brunet’s translation rather closely parallels it in organization and manner. But he offers little commentary, no Greek text, and a far shorter index of plants (Brunet 1933-1937, vol. 4:270-83).

British Library, London reproduced from Gaspard Fossati, Aya Sofia, Constantinople (London: Colnaghi & co, 1952)

Alexander’s Early Life and Medical Education

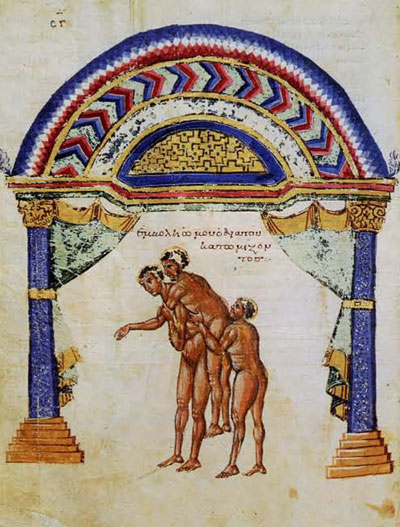

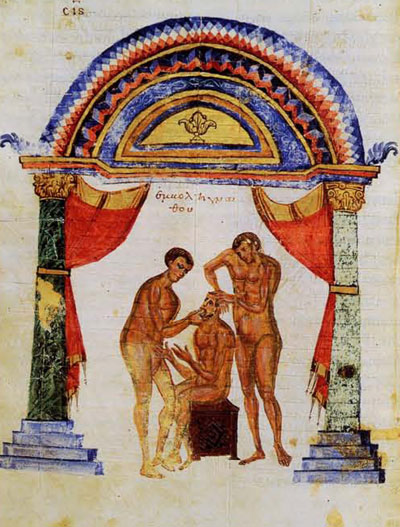

Alexander therefore probably learned bone setting, suturing of wounds, cauterization, and administration of anesthetics… through what we would term an “apprenticeship” in surgery

Brunet at least inflates the story of Alexander’s life and times from some good historical evidence. Most prominent notables in ancient and medieval medical history are known only through their own treatises, but this is not the case for Alexander of Tralles. One finds biographical details about him and his four brothers in the writings of the Byzantine historian Agathias. According to Agathias’s history of the mid-6th century AD, Alexander was born in AD 525 in Tralles (Lydia), the son of a physician named Stephen (Histories 5.6.3-6). Stephen apparently reared his five sons carefully, in the manner appropriate to a well-educated citizen of the Byzantine elite. All of them became prominent in their professions: Anthernius was the architect-engineer who redesigned the magnificent Hagia Sophia for Justinian (Fig. 3); Metrodorus rose to eminence as a master grammarian; Olympius became one of the most learned jurists of his day; and Dioscurus was, like his father and brother, a physician.

Education at the elementary level took place in the home. There were no medical schools or training facilities in Justinian’s time, and argument among specialists has not settled the question of whether there were such things as bonafide hospitals in the 6th century. Most likely Alexander would have learned his medicine from a master-teacher (perhaps his own father). There is likewise no evidence of formal training in anatomy at this period. Surgical texts, exemplified by Hippocrates’ Wounds of the Head, Fractures, and Joints, are unusual in Greco-Roman and Byzantine medicine.

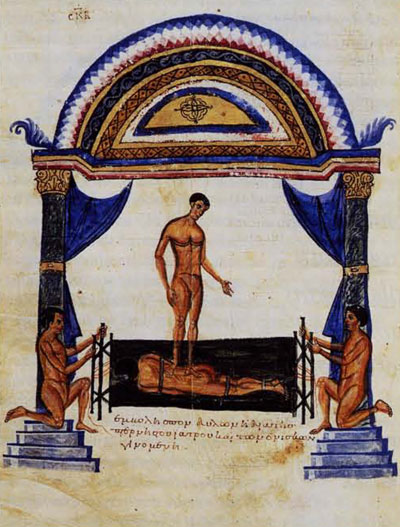

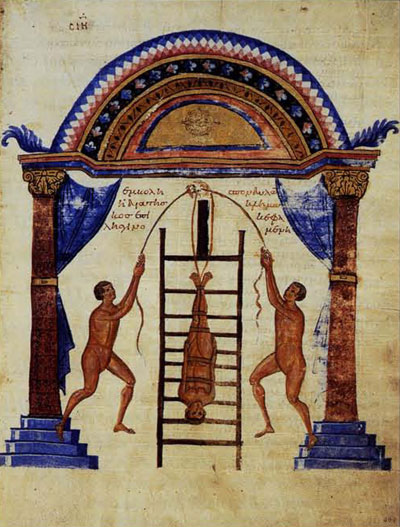

Alexander therefore probably learned bone setting, suturing of wounds, cauterization, and administration of anesthetics (mandrake and opium were the most common) through what we would term an “apprenticeship” in surgery (Figs. 4, 5).

As is shown by the famous Vienna Manuscript of AD 512, the most important medical authorities in the early 6th century were Galen of Pergamon (AD 129—after 210) and Dioscorides of Anazarbus (flourished ca. AD 65 or 70). Somewhat surprisingly, the familiar figure of Hippocrates of Cos (fl.ca. 425 BC) is simply absent. This unexpected neglect by 6th century authorities of the so-called Father of Medicine is highlighted by Alexander’s citation of some three dozen specific passages from Galen’s works, while quoting Hippocrates only through Galen (in about twenty instances).

The Itinerant Physician

Agathias implies that Justinian knew well the varied talents of at least three of Alexander’s brothers. Anthemius became the emperor’s chief architect and court engineer, Metrodorus was actually involved in the schooling of the children at the royal court, and Olympics probably was consulted by Justinian the compilation of the Digesta (the codification of Roman jurists that appeared in AD 533) and its supplements known as the Novella. The fourth brother, Dioscurus, “lived out his life in his native city, where he practiced his profession with remarkable distinction and success” (Agathias 5.6.5 [Frendo 1975:1411). He could easily have become a medical consultant to Justinian’s court at Constantinople at appropriate times. In contrast, Alexander “took up residence in Rome, whither he had been summoned to occupy a position of great distinction” (ibid.) and so, Brunet’s claims to the contrary, need not have been involved in the life of the court.

Alexander clearly had a touch of wanderlust, since the texts indicate he traveled extensively before he settled in Rome. This is, of course, quite in keeping with the ancient tradition of the itinerant physician, who journeyed from settlement to settlement, picking up tips as he went, setting down data that might or might not be a part of his formal written sources, trying new substances or treatments, and then after a while moving to another locale. In his approaches to gathering information, Alexander reminds one immediately of Dioscorides of Anazarbus (Fig. 5), testing the recommendations of the classical medical authorities on actual patients and making extensive notes on what worked and what did not prove useful among surgical techniques, drugs, and therapeutic regimens. As a doctor, he spent much time especially in Spain, Gaul, Corcyra, Thrace, and Italy, and his extant writings indicate his wide experience, particularly in pharmaceutical lore. One has a vivid impression, when reading through the treatises of Alexander of Tralles, of an active, inquisitive, and kindly physician, traveling from town to town, from province to province, residing for a time in one place dispensing drugs and performing simple and complex surgical operations (Figs. 6-9). It is likely too that Alexander had several apprentices who accompanied the master physician, until both student and instructor judged that sufficient skill and expertise had been attained by the younger man. Such seems to have been the system of medical training in the Roman and Byzantine epochs.

Alexander of Tralles became a physician of enormous experience, respected in his practice and (if Agathias is to be trusted) of widely known eminence. He was a doctor who knew his Greco-Roman medical classics, but who listened to country dwellers and sophisticated city-slickers alike to gain new information on treatments for troublesome diseases. Illustrative is an example drawn from his account of the treatment for the Falling Sickness (epilepsy; Twelve Books 1.5). Alexander records what he has learned from a layman in Corcyra, someone named Marsinus of Thrace, then sandwiches such local and folk-medical sources together with quotations on the use of amulets from the authoritative works of Archigenes (fl. AD 98-117) and Damocrates (fl.ca. AD 50). The use of these two written sources in conjunction with Corcyrean folklore is suggestive of how Alexander combined book-learning with personal experience, cross-checking what the texts recommended with what he saw and heard, much in the manner of Dioscorides.

Puschmann and Brunet both note that Alexander believed in the efficacy of amulets and charms, and even now physicians debate the placebo effect in cures. Puschmann approach to this old problem is probably the most practical: as one of the finest of the early Byzantine practitioners, Alexander certainly was aware that a patient’s belief (however defined) quite frequently contributed to improvement, if not to a cure. Alexander’s works reveal a consummate skill in the combinations of pharmacology, the application of diagnostics and surgery, and—that most important of medical gifts—the innate understanding of what the patient needs and how (sometimes under trying circumstances) to ensure proper treatment in the face of a patient’s reluctance. This is, of course, quite in line with Alexander’s acceptance of magical incantations, amulets, and magico-medical charms as useful when appropriate.

One curious sidelight is important, since it aids our understanding of how Alexander of Tralles knew and described Far Eastern drugs, some of which were known to Dioscorides, but some of which (e.g., cloves) were new in Byzantine pharmacy. Alexander dedicates his compilation of medical experience to a “Cosmas” (Puschmann 1878-1879, vol. 1:289) and explains that Cosmas is the son of a man who—along with his father, Stephen—was fundamental in forming his character and outlook on life. One can, therefore, conjecture that Cosmas’ father and Cosmas himself acted as tutors and learned friends of the family in roles left undefined by Alexander. We know of a Cosmas Indicopleusts, the famous “Navigator of the Indian Seas,” who left us a curious travelogue of Sri Lanka (Ceylon), Arabia, and India, reflecting an active Byzantine commerce with the Indian subcontinent in the 6th century. If he is the “Cosmas” of Alexander’s dedication, the connection would explain Alexander’s solid knowledge of Far Eastern pharmaceuticals.

Wein, Oserreichische Nationalbibothek, Cod. Med. gr 1, folio 5v.

The Twelve Books

Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Codex Laurentianus 74.7:c. 198v

Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Codex Laurentianus 74.7:c. 1203v

Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Codex Laurentianus 74.7:c. 200

The Twelve Books form the bulk of Alexander’s extant works and probably represent his last writings before he died in Rome in AD 605. Alexander writes in his dedication that this, his great work on medical practice, was set down in old age, after he could no longer bear up under the fatiguing pace of an active practice. He explains that the compendium on medicine is written at the request of his friend, Cosmas, and that the full text is intended to be useful in describing, in the clearest way possible, the best forms of medicine and medical therapeutics (Puschmann 1878-1879, vol. 1:288). By the same token, his justly famed Letter on Intestinal Worms is composed at the wish of another friend, an unknown Theodorus, so one must assume that Alexander had many friends, patients, and acquaintances who begged him over the years to set down his medical experiences. The manuscript traditions are rather muddled, so that one remains uncertain if Alexander’s Treatise on Fevers is another response to Cosmas’ entreaties, or whether the full Twelve Books on medicine honor that particular request.

Alexander’s Twelve Books comprise a listing of various ailments and their treatments—with a very rich pharmacology of about 600 drugs—beginning with alopecia and hair-loss, nicely directed and suggestive of Alexander’s foppish patients among the upper classes. Book I considers “diseases of the head” and includes “lethargy.” Alexander’s acceptance of the traditional Hippocratic theory of humoral pathology (as made canonical by Galen) shows in his class of “melancholy,” the affliction that is characterized by an excess of black bile. (The other three humors were blood, phlegm, and yellow bile; in health, all four would be in krasis, or in “proper proportion.”) Book II is on eye diseases, oddly brief in view of the details provided in the seven chapters of Book III, which take up ailments of the mouth and the salivary glands. (What we call “cankers” were rather common in the 6th century.) Book IV is another fairly short account, addressing heart trouble (our angina is recognizable in a general sense). Book V devotes six chapters to lung diseases, and one is struck by the very often repeated occurrence of various types of pneumonia. Book VI is a single chapter on pleurisy, and Book VII takes up stomach problems in nine chapters (one cannot escape the impression that Alexander had performed some dissections, so accurate are the descriptions of anatomy).

Book VIII reviews (in two chapters) intestinal diseases; the first chapter is on “cholera,” while the second is simply called “colic.” Suggested frequently are baths, and the final recommendations are given over to some fascinating amulets, talismans, and charms, which—as Alexander says often enough—may help patients and certainly will not harm them. Book IX (in two chapters) surveys liver ailments, quoting directly and indirectly from the works of Galen. Here one meets another disease engendered by the presumed excesses of one of the humors, in this instance yellow bile. Investigation of diet is the major method by which Alexander indicates a cure or at least an improvement for the familiar jaundice, and the physician recommends some radical alterations in the patient’s diet quite similar to a modern doctor telling patients to give up fatty acids. Book X (in two chapters) speaks to “dysentery” and “hydropsy,” and Alexander classes them as the two major kinds of abdominal afflictions. The first is the kind of ceaseless diarrhea (showing that the body is attempting to expel an excess of water) characterized by too much phlegm, while the second stems from the retention of too much fluid. Of interest is that “dropsy” was a valid diagnosis until the late 19th century. Until the discovery in the late 19th century of the causative bacteria (Shigella spp.), transmitted by the numerous flies gathering around human waste, “dysentery” (often fatal to youngsters and the elderly) remained a similarly accepted diagnosis for a continuously watery diarrhea, until public health measures (especially regarding water supply) became commonplace in the main metropolitan centers of Europe and America.

Book XI has eight sections in two chapters on afflictions of the genitals and urinary tract, and the subtitles indicate the most commonly occurring problems: (1) kidney stones; (2) inflammation of the kidneys; (3) diagnosis and treatment of strangury; (4) bladder stones; (5) diagnosis of a “psoriatic bladder” (perhaps applied by analogy from skin diseases, since Alexander suggests treatments against “flakes” in the urine); (6) diabetes; (7) damaged or diseased penis; and (8) priapism. Book XLI is a long, undivided account of podagra or gout, with numerous recommendations for treatment, including the use of the very effective (and still employed) autumn crocus (Colchicum autumnale L.). Alexander apparently wrote several other medical tracts that have not survived. He expressed an intention to write a book on fractures and wounds (in the manner of Hippocrates), and there is evidence of a lost work on urines and their classifications under the name of Alexander known to Byzantine physicians. A tract under the name of Alexander on ophthalmology was translated into Arabic, but no trace of the original Greek work itself remains—if there was one.]

Illustrations of Early Bone-setting Procedures

Hippocrates’ works—Wounds of the Head, Fractures, and Joints—are among the few surgical texts in Greco-Roman and Byzantine medicine. Alexander of Trellis is more likely to have learned bone setting through an apprenticeship, perhaps even to his own physician-father, Stephen.

Apollonius of Citium was active ca. 50 BC as a physician at one of the Ptolemaic courts (the one on Cyprus is suggested by his name and title). We know almost nothing about him, except that his Commentary on the Hippocratic Joints is the only one to survive intact. The text we have was recopied sometime in the 9th or 10th century AD, and the illuminations that accompany it (Figs. 6-9) were painted at the same time (Kollesch and Kudlien 1965). Alexander himself apparently intended to write a book on fractures and wounds in the manner of Hippocrates.

The Pharmacopoeia of Alexander

In the organization of the Twelve Books, Alexander follows what might be called a Hippocratic model, in that first he discusses the disease and its characteristics, then suggests treatments (if any). For each disease he supplies descriptions, stages of development, recommendations for treatments, whether the illness was chronic or acute, whether a krisis signaled a cure or the onset of death, or if the kritis was but one of many in a chronic illness (quite characteristic of fevers). Alexander had mastered a phenomenal variety of drugs, both in their “simple” forms and in the compound formulas almost always typical of his treatments for diseases. The Twelve Books fairly bulge with formulas, recipes, and measures for the compounding of drugs.

Almost all of the 600-odd substances included in the great Materia Medica of Dioscorides are here, but with a different twist. Instead of merely copying out the old recipes from a written text, Alexander often changes ingredients, frequently rearranging substances, as can be seen when his recipes are compared to similar ones in Galen, Oribasius, and others. Unlike many of our ancient and medieval medical texts, there is rather less veneration for a traditional source simply because it chances to be an authoritative medical tract.

Alexander does not particularly focus any of his works on drugs, but pharmaceutical therapy is extremely prominent throughout each subdivision. Listings of drugs follow descriptions of ailments in almost all special sections, including fevers, headaches, what modern readers might call “nervous diseases” (e.g., melancholia), ophthalmology, the noteworthy Letter on Intestinal Worms, lung diseases, gout, and so on. A number of the drug recipes seem to be original, although the specific ingredients have almost always been used and defined in earlier Greek, Roman, and Byzantine pharmacology.

An illustration of how late ancient and early Byzantine medicine was not utterly static is nicely instanced by the new names provided to given ingredients by Alexander. Consider, for example, the “Armenian Stone,” part of a recipe in Treatise On Fevers 7 (Quartans) (Puschmann 1878-1879, vol. 1:428-31). Earlier Greek texts, including the Papyri Graecae Magicae (12.201), had noted the usefulness of ios chalkou (verdigris, or copper oxyacetate, approximately [C²H³0²] Cu.Cu[OH]².5H²0), but here Alexander’s Armeniakos lithos has taken the place of ios chalkou. This new substance had been foreshadowed in Dioscorides’ Materia Medica (5.90), and if we understand the geological chemistry of the “Armenian Stone,” it is now a combination of copper oxyacetate, azurite (approx. 2CuCO³. Cu[OH]²), and malachite (approx. CuCO³.Cu[OH]²). Roman and Byzantine pharmacy easily substituted one kind of copper oxyacetate for another, and Alexander’s “Armenian Stone” occupies the same role that was employed by verdigris in earlier prescriptions.

Moreover, Alexander’s recipes give precise dosages and measures, thus easily exploding the commonly repeated statement in general textbooks on early medicine that weights and measures were unimportant in pharmacy and medicine before the Renaissance. The remainder of Alexander’s “On the Armenian Stone” shows how his new pharmacy consisted of rearrangements of ingredients according to his own experience in pharmaceutical therapies: The stone called “the Armenian” administered washed or unwashed in a dosage of 4 keratia [ca. 800 mg/12 grains] works well for all forms of quartan fever, since it acts as no other drug for the evacuation of black bile. Washed in water, it completely purges the lower bowels, but unwashed it is an emetic that does not cause too much heating, unlike the others. But if some [of your patients] regard the solution of “the stone” with distaste, make little pills employing the following ingredients:

4 grammata of pikras [a mixture of aloe and honey]

3 grammata of epithymon [the lesser dodder, Cuscuta epithymon (L.) Murr.]

1 gramma of agarikon [probably a tree mushroom of the Boletus spp.]

1 grammar of Armenians lithos

5 “berries” of karyophylla [cloves, Eugenia caryophyllata Thunb.; here the sun-dried, unopened flower-buds]

5 grammata of skammonia [scammony, Convolvulus scammonia L.].

Mix with juice of kitrion [citron, Citrus medico L.], or with krokomelon [a jam or jelly made from quince, Cydonia oblonga Mill.] and saffron [Crocus sativus L.] or with rhodomelon [a jam made from roses, generally Rosa gallica L., and quince], or with rhodomelon [a rose-honey mixture]; the dosage is 2 grammata. [1 gramma = 1.2 grams = 1 scruple = 20 grains] (Puschmann 1878-1879, vol. 1:429, 431; trans. from Greek by author)

It is worth noting that an alchemical papyrus from late Roman or Byzantine Egypt also records the combination of water with verdigris, so Alexander has recommended what was a common practice of washing the green rust that is copper oxyacetate. The other substances in the recipe appear in earlier Greco-Roman medical and pharmacological texts, with the exception of the cloves (Pliny mentions them in his Natural Histoty [12.30], but they are rare and quite exotic). By the Byzantine period, cloves are not uncommon (at least to the learned physician). Their inclusion in this and other recipes may lend credence to Alexander’s supposed association with Cosmas Indicopleustes, or at least may reflect a special connection with the spice trade from the Far East in the 6th century.

The text of Alexander’s Treatise On Fevers as a whole shows a careful assessment of drugs set within the context of a then-ancient humoral pathology. The recipe quoted above is rather typical in the works of Alexander, who includes nearly 500 of them throughout the various writings we have by him. Alexander’s pharmacy indicates that Byzantine medicine as a whole was neither static nor repetitive: it illustrates a continual effort by the best of the early Byzantine physicians to use a traditional pharmacopoeia in fresh arrangements, while retaining the overarching theoretical context of Galenic humoral pathology. Alexander’s surgical techniques were also quite successful, as one learns of various treatments for bone setting, dislocations, and the like. It is quite surprising that a full-fledged study of this magnificent physician has not yet been produced by modern medical historians.