The University Museum Archives represents a unique resource for researchers in archaeology, anthropology, history, classics and related fields. A preliminary survey done in 1979 indicated that the Museum currently holds about 2000 linear feet of records, of which about a third are field records collected between 1885 and 1955. These are field notebooks, indexes, catalogues, maps, drawings, field photographs, correspondence, and reports generated during the Museum’s almost 100 years of research. These records reflect the development of the fields of archaeology and anthropology, document the scholarly work done by Museum expeditions, and establish the context of the Museum’s rich collections. With the help of a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the older field records were transferred to the recently renovated Elkins Library in the Museum, where they are being sorted and conserved. Written descriptions for each group of records are also being prepared to serve as ‘finding aids’ for researchers. Since the papers are arranged by geographical area, the Archives staff is slowly working its way around the world, rediscovering both the well-known and the forgotten expeditions in the Museum’s past.

Most recently work was completed on the Alaskan papers, which reflect the University Museum’s long-standing interest in the Arctic. Initiated in 1905, active research in Alaska continued into the mid-1970s, sustained in part by the special concern of two Museum directors, George Byron Gordon (1910-1927) and Froelich Rainey (1947-1976). The Museum fielded both ethnographic and archaeological expeditions, directing the main thrust of its research toward the early history of man in the area. The artifacts recovered by these expeditions form a substantial part of the University Museum’s extensive Alaskan collections. The scientific results they generated were widely reported in a number of scholarly publications.

The Alaskan holdings of the University Museum Archives cover only part of this long sequence of research, but contain a fascinating glimpse into the personalities and work of past Museum investigators. The earlier explorations are particularly well represented. Their papers include correspondence, original field notes and drawings, photographs, news clippings, manuscript drafts of articles and artifact inventories. This documentation helps reconstruct the details of the expeditions, from initial planning to final results, and serves to recreate the flavor of their times.

Perhaps the best-remembered explorations are those of Louis Shotridge and Frederica de Laguna, who both worked in southeast Alaska. Altogether, their work spanned over half a century and furnished the Museum with important collections. The Museum also sponsored early expeditions further to the north and west, however, among the Bering Sea and Bering Strait Eskimo. Though maybe now less well known, these expeditions had a significant impact on the scientific thought of their day. Well-publicized, they helped build the Museum’s reputation as an important center for anthropological research.

Explorations in the north were pioneered for the Museum by G. B. Gordon. He made two trips, one in 1905 and the other in 1907, while he was Assistant Curator of the Museum’s Section of General Ethnology and American archaeology, before his tenure as director. The original field notebooks for both trips, correspondence and a large collection of photographs are all present in Archives. According to a 1905 letter written by Gordon, he chose Alaska as an area for research because he wanted to visit native Americans in “those districts where the white man’s influence had been least felt.” Gordon felt that it was a prime area for conducting original ethnographic research and securing rich collections for the Museum. He also wanted to see how much change had occurred since the reports of the first ethnographic explorers, notably Edward Nelson in the 1870s. Gordon recognized a certain urgency to his task, as the news of gold discoveries was attracting more and more white prospectors and threatening the demise of native cultures.

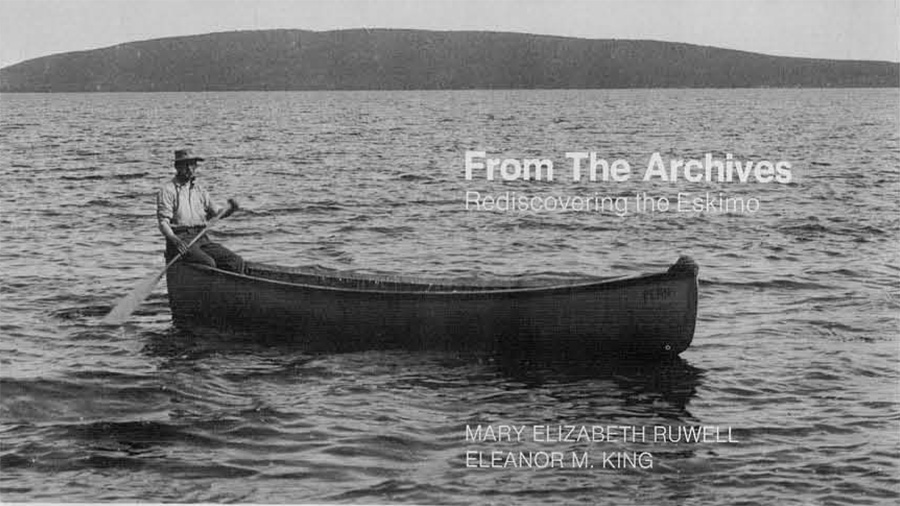

With these objectives in mind, he undertook a preliminary reconnaissance in 1905 with his brother, MacLaren Gordon, a mining engineer familiar with the Yukon Territory. They went by canoe up the Kantishna, a river hitherto unexplored by the whites, and portaged over a short, hitherto unexplored divide to the headwaters of the Kuskokwim which they reached at the end of the short Arctic summer. A second expedition in 1907 led them successfully down the Kuskokwim and eventually back to Nome, Alaska, after twenty days adrift on the Bering Sea.

Gordon’s notes for both trips reveal an eclectic interest in language and customs. He had a special penchant for collecting cat’s cradles, a favorite subject of scholars at the turn of the century because of their wide distribution in cultures around the world. He also enjoyed observing people and relates amusing anecdotes about them. His notebooks include sketches of the surroundings and crayon drawings of Eskimo children. The 1907 expedition was the source of a popular travelogue In the Alaskan Wilderness, which he published in 1917 in memory of MacLaren who had been killed on the Somme in 1916. The Archives has the original illustrations for this story, drawn by the well-known Museum artist, M. Louise Baker.

In 1917 John Wanamaker, Vice-President of the Museum’s Board of Managers, sponsored William V. Van Valin to make ethnographic observations and collections in the area around Point Barrow, the northernmost point of land in Alaska. A former Alaskan school teacher, Van Valin had long years of experience in the wilderness, and knew the territory and its inhabitants well. At first he concentrated on recording all aspects of Bering Strait Eskimo life, particularly the famous whale hunt, through film, photography and phonographic records. In 1918 one of his informants, an Eskimo named Ootoyuk, reported finding human bones protruding from a mound of earth on the tundra about eight miles from the Barrow settlement. This mound and several others like it had previously been assumed to be weathered glacial deposits. What Van Valin found instead was that some at least contained the well-preserved skeletons of men, women and children, many still wrapped in skins and furs and accompanied by an assortment of tools and utensils. From the wooden construction inside, Van Valin deduced that the mounds were ancient igloos, whose inhabitants had been overcome by some natural disaster such as starvation or disease. He seems to have held to this belief despite later investigations which showed that the ‘igloos’ were in fact prehistoric burials.

The news of Van Valin’s archaeological discoveries caused quite a sensation upon his return to Nome in September 1919. Newspapers gleefully recounted his find of `frozen people’ and speculated on the mystery of their death. In the open debate over sudden versus slow catastrophes, one of the most delicious lines came from the November New York Herald story: “Mr. Van Valin does not believe that the village was overwhelmed by a glacier…”

Enjoying almost equal prominence with the skeletons was Van Valin’s youngest child, a boy born during the two-year expedition in Point Barrow. Widely heralded as the “Snow Baby” (and often misrepresented as a girl), the child was touted as the second white baby ever born in the Arctic. Van Valin later referred to him in a 1945 letter to George Vaillant (then director of the Museum) as: “… the most valuable biproduct of the late Hon. John Wanamaker Expd’n…”

By 1928, Museum analyses of Van Valin’s remarkable discoveries had further aroused scientific interest. J. Alden Mason studied the artifacts found in association with the skeletons and determined that they belonged to the archaic Eskimo Thule Culture. This conclusion excited the interest of Arctic archaeologists, for it meant that the Point Barrow sites were the first where excavated human remains had been found with Thule objects. Concurrently, the skeletal material had been turned over for analysis to the Wistar Institute and Dr. Ales Hrdlicka of the Smithsonian Institution. The result of the investigation was that the skeletons were of a radically different physical type from the modern Eskimo inhabiting the area. Furthermore, in Hrdlicka’s words, they “resemble[d] to the point of identity the physical type of the present Eskimo of Greenland.”

In a thoughtful review of the problem, Mason suggested that the Eskimos of the Thule culture were the pan-Arctic ancestors of the present Eskimo, whose culture and physical type had been modified differently in different areas by admixtures of other populations. He went on to propose that in Alaska the modern Eskimo were the descendants of both the ancient Thule and local Indian populations, and therefore physically distinct from both. The announcement of Hrdlicka’s and Mason’s results attracted considerable interest at the September 1928 meetings of the International Congress of Americanists in New York. [Current interpretation differs from Mason’s. The artifacts Van Valin excavated are now attributed to the Birnirk Culture (A.D. 500-1000), which precedes the Thule Culture (A.D. 1000-1850) in the Barrow area, Also, despite similarities in material culture, there is no basis for believing in a genetic intermixture of Eskimo and Indian populations.]

Shortly after these sessions, Hrdlicka received word from Point Barrow that heavy looting was destroying the sites. Several mounds remained intact, however, and promised to yield as complete and well-preserved an archaeological sample as those excavated by Van Valin. Hrdlika also learned that local opinion in Barrow concurred with Arctic scholars in doubting that the mounds were really igloos. He wrote to Mason who in turn persuaded the Museum to finance further excavations at Point Barrow. Accordingly, in 1929 the Museum contracted Arthur Hopson, a Point Barrow resident, to investigate more of the ancient structures and compare them to abandoned igloos in the same area. Hopson’s work confirmed that the sites were the ruins of driftwood charnel houses representing a type of burial unknown before in the Arctic. His excavations also added substantially to the collections already made by Van Valin.

Though the Museum did no further work at Point Barrow, the sites continued to attract scholarly interest in subsequent years. Frederica de Laguna made detailed notes on Van Valin’s collection while helping to recatalogue it in 1935, and in 1957 James Ford, an archaeologist from the American Museum of Natural History, excavated again on the peninsula. During the course of his investigations he was able to pinpoint the hitherto uncertain location of the mounds excavated by both Van Valin and Hopson. This information he passed on to the University Museum, along with some delightful comments on their earlier work.

Later this year, the Museum, in cooperation with Bryn Mawr College, plans an Eskimo exhibit featuring artifacts collected by Gordon, Van Valin, Hopson, de Laguna and others. The objects, set in context, will offer the public a vivid opportunity to see how the Eskimo lived and worked, and to admire their skilled artistry. The collectors themselves will be represented only by names on labels, but the material in the Museum Archives brings their enterprise and personalities to life, giving the story behind the results.