The archaeologist leaves for the field with his mind full of the historical problems he will solve through further excavation. His expedition’s entire field campaign has been planned around these problems. Yet he also knows that though further field work will provide some of the answers to the questions posed, it will also raise new questions as yet unasked. Simultaneously as he chips away at the boundary between the known and the unknown, the mass of the unknown continues to expand. Sometimes, through a discovery he could not possibly have anticipated, he is able to take a sudden leap forward–a leap that carries him well beyond his immediate frontiers. Suddenly he recognizes the full extent of his ignorance, the extensiveness of which he has not even suspected. Such a discovery was made by the Hasanlu Project during the 1961 field season.

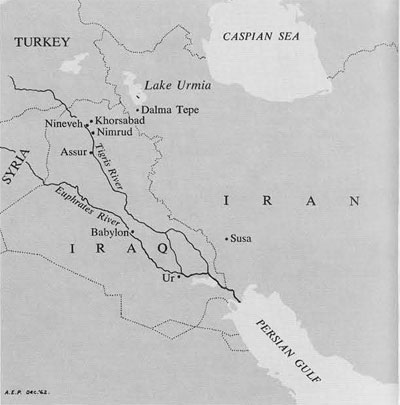

In earlier seasons of excavation in the Solduz Valley of northwestern Iran, the Project had made preliminary soundings at Dalma Tepe, a small mound some three miles southwest of the great mound of Hasanlu. These soundings revealed the presence of a painted pottery culture of the fifth millennium B.C., unique amongst the cultures of the time in the Near East. Further excavations were planned for 1961 to explore these preliminary discoveries. When these excavations were complete the Project had stepped into the very center of darkness that shrouds the fifth millennium B.C. in this part of the world.

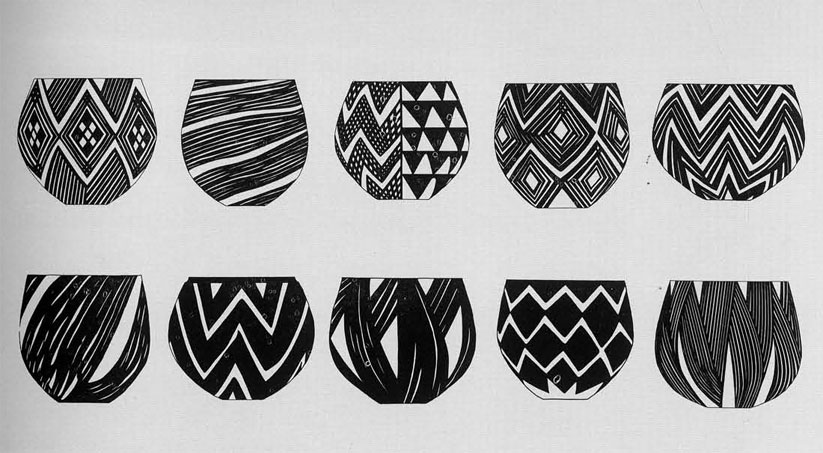

Several of the many painted vessels recovered from Dalma Tepe during these excavations are illustrated here. The ground color of this pottery is either a light pink-buff, the natural color of the fabric, or is cream slipped. Against this light ground, designs are drawn in a light maroon or a maroon-black paint. The inside of the vessel i s usually covered with a maroon-red slip. The fabric is tempered with straw, a technique common in the fifth millennium in northern Iraq and Iran. The ware crumbles easily and is not well fired. None of the shapes discovered is complex or unusual. In short, from the technological standpoint, there is nothing remarkable or unique about Dalma Painted Ware.

Yet when one directs attention to the decoration of this painted ware, it is at once clear that here is an artistic tradition of the highest order. It is its style that makes Dalma Painted Ware unique. The range of motifs used by the Dalma potters is in itself remarkable. Thus far, only geometric designs are known, but within that limitation one finds not only the motifs illustrated here but many others as well. The potters of the period apparently gave their imagination free reign and sought to explore almost every avenue of geometric design open to them.

Yet when one directs attention to the decoration of this painted ware, it is at once clear that here is an artistic tradition of the highest order. It is its style that makes Dalma Painted Ware unique. The range of motifs used by the Dalma potters is in itself remarkable. Thus far, only geometric designs are known, but within that limitation one finds not only the motifs illustrated here but many others as well. The potters of the period apparently gave their imagination free reign and sought to explore almost every avenue of geometric design open to them.

This desire for artistic exploration and improvisation carried them beyond the limits of sound composition in some instances. The “half and half” vessel illustrated is not a modern draftsman’s nightmare, but an actual vessel as found. One half of the pot’s exterior is painted with a cross-hatched zigzag pattern, the other half with rows of solid hanging triangles. Each design is in itself artistically pleasing, but the two together can hardly be called an integrated composition.

Another aspect of the artistic achievement of the period is the relationship sometimes emphasized between the painted design and the ground color of the pottery. These artists were experimenting with the effect of “negative painting,” found in the interplay of design and background. Given instances where only thin lines of ground color show through the paint, one wonders whether one is supposed to see the painted design or the pattern left in the areas of the vessel that have not been painted. The answer is both, as a kind of optical illusion occurs. The painted design and the pattern left in the ground complement and reinforce each other, making the whole more pleasing to the eye.

The experimental and inventive aspects of the Dalma period are clearly seen not only in the motifs used, but also in their execution. All of these painted vessels are done with a characteristic boldness and stylistic vigor. Within this framework, however, one may compare, for example, precise diagonal lines on one vessel which appear to have been drawn with a straight-edge, with the free and almost wildly modern application of the same motif on another. The vessel in the first instance suggests an artist with a tight, precise, careful mind; in the other, an artist with an loose and rambling spirit. Yet vessels decorated in both of these styles flourished in the same period at the same site. Let the archaeologist who would enforce artistic limitations on the ancients through modern typology beware!

The comparative study of other finds which accompanied this painted pottery and a single radiocarbon date confirm an original guess that this culture dates to the fifth millennium B.C. Thus the Dalma painted ware can be properly placed in the chronological framework of the ancient Near East. Furthermore, the unusual bowl illustrated with a “double W” pattern framed in a double crescent, which was certainly an import in the assemblage, indicates that the Dalma culture was in contact with other painted pottery traditions. But until further field work is undertaken, the native artistic tradition discovered at Dalma Tepe will remain a unique spot of light deep in the darkness of its time and area. Until the origins and cultural connections of this tradition are understood, we will continue to be impressed with what we do not yet know about the fifth millennium. And so it is that a new discovery, unanticipated by the archaeologist, both shows us how extensive is the darkness which surrounds us, and gives us a starting point from which to ask more questions of the unknown.

The comparative study of other finds which accompanied this painted pottery and a single radiocarbon date confirm an original guess that this culture dates to the fifth millennium B.C. Thus the Dalma painted ware can be properly placed in the chronological framework of the ancient Near East. Furthermore, the unusual bowl illustrated with a “double W” pattern framed in a double crescent, which was certainly an import in the assemblage, indicates that the Dalma culture was in contact with other painted pottery traditions. But until further field work is undertaken, the native artistic tradition discovered at Dalma Tepe will remain a unique spot of light deep in the darkness of its time and area. Until the origins and cultural connections of this tradition are understood, we will continue to be impressed with what we do not yet know about the fifth millennium. And so it is that a new discovery, unanticipated by the archaeologist, both shows us how extensive is the darkness which surrounds us, and gives us a starting point from which to ask more questions of the unknown.