In September 1997, I lectured on “Ancient Wine and the Vine” cup and down the West Coast. In the heartland of the New World “wine culture,” I offered an early history of the Eurasian grapevine ( Vitas vinfera). This species accounts for nearly all modern red and white wine, and research in my laboratory has shown that it was used to make wine more than 7000 years ago in the Old World (see Expedition 39, no. i). But where and when did winemaking first begin?

Beyond its entertainment value, archaeo-chemical research on ancient wine has significant scientific potential. The original habitat of a plant is often the region of greatest genetic diversity. Aboriginal traits represented in this gene pool can be recovered and used to protect today’s grapevine from injury and disease. Ancient winemaking practices. based on long-established tradition, can also be the basis for innovations in the present. Aging in toasted oak barrels was introduced in California winemaking only thirty years ago, but recent analyses show that it dates back to at least 1700 BC on Crete. We stand at the end of a long, largely successful experiment in viniculture, but how many other discoveries are lurking in our archaeological past, especially in the Caucasus?

It has long been hypothesized that the wild Eurasian grapevine was first taken into cultivation during the Neolithic period (ca. 8500-4000 BO in the mountainous regions of the Caucasus, between the Caspian and Black Seas. Once the plant was domesticated, so the theory goes, wine would be made in greater quantities, and its production and consumption integrated into Neolithic culture and cuisine. Vine cuttings were then successively transplanted to other parts of the ancient Near East and Egypt. A distinctive wine culture, replete with socio-religious conventions and drinking paraphernalia, encouraged this development and traveled with the vine. Over the millennia, viticulture and winemaking spread to other temperate climates around the world.

No one, however, has ever put the theory of the Caucasian origin of viniculture to the test. Now that the political turmoil in the region has settled down, the time is ripe for such an investigation. In October 1998, I traveled to Tblisi, Georgia, and Yerevan, Armenia. My hosts included the directors of the national museums and archaeological institutes, together with specialists on the earliest history of the two countries—in particular, Tamax Kiguradxe and Ruben Bedalian. They arranged for me to examine their Neolithic pottery collections and to meet with top winemakers and viticulturalists.

No one, however, has ever put the theory of the Caucasian origin of viniculture to the test. Now that the political turmoil in the region has settled down, the time is ripe for such an investigation. In October 1998, I traveled to Tblisi, Georgia, and Yerevan, Armenia. My hosts included the directors of the national museums and archaeological institutes, together with specialists on the earliest history of the two countries—in particular, Tamax Kiguradxe and Ruben Bedalian. They arranged for me to examine their Neolithic pottery collections and to meet with top winemakers and viticulturalists.

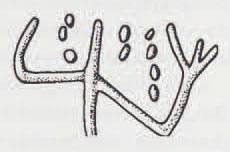

The invention of pottery during the Neolithic period was crucial for processing, serving, and storing the many new foods and beverages, including wine. The Neolithic pottery from Georgia, predating 6000 BC, is especially impressive. Jars, some with reddish residues on their interiors (wine lees?). were decorated with exterior appliqués which appear to be grape clusters and jubilant stick-figures, arms raised high, under grape arbors (see line drawing). The Georgian pottery will be subjected to the same battery of scientific analyses that led to the discovery of the ca. 5000 BC vintage from the Museum’s excavations at Hajji Firuz Tepe in northwestern Iran.

A second, related research avenue to determine when and where the Eurasian grapevine was first domesticated involves DNA analysis to uncover the genetic “history” encoded in the wild Eurasian grapevine and its cultivars. The so-called Noah hypothesis posits that this horticultural advance occurred in the Caucasus. The hypothesis is aptly named for the biblical patriarch, who is said to have planted a vineyard on Mt. Ararat within sight of modern Yerevan.

I returned from Georgia and Armenia loaded down with leaves from all the principal local red and white grapes, with such exotic names as Rkatsiteli, Mikhail, and Chishmish, as well as specimens of the wild vine and a variety transitional to the domesticated. I also collected samples of ancient grape seeds and even wood (sometimes reverently covered with silver foil) identified as belonging to the same varieties that grow there today. Prof. Revaz Ramishvili, the head of University of Georgia’s viticultural department, went so far as to say that he was parting with his “soul” when he presented me with one of six pips that came from 8000-year old grapes. The grape samples will be analyzed in Dr. Carole Meredith’s DNA laboratory in the Department of Enology and Viticulture at the University of California at Davis.

Special acknowledgment: The initial “seed money” for the “Ancient Wine and DNA Project” was generously provided by Penn alumni on the West Coast, Philip S. Schlepp (C’57), and Robert H. (C’50) and Beverly Brunker (CW’51).