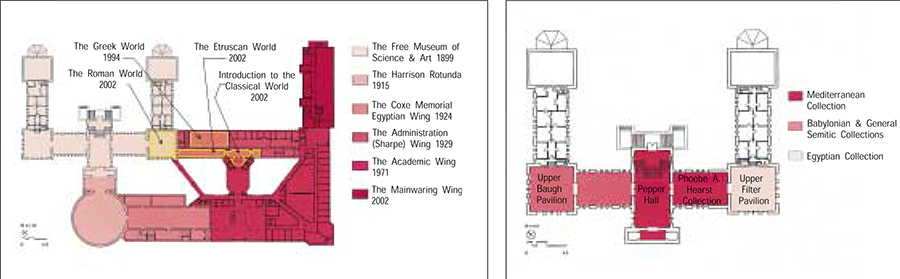

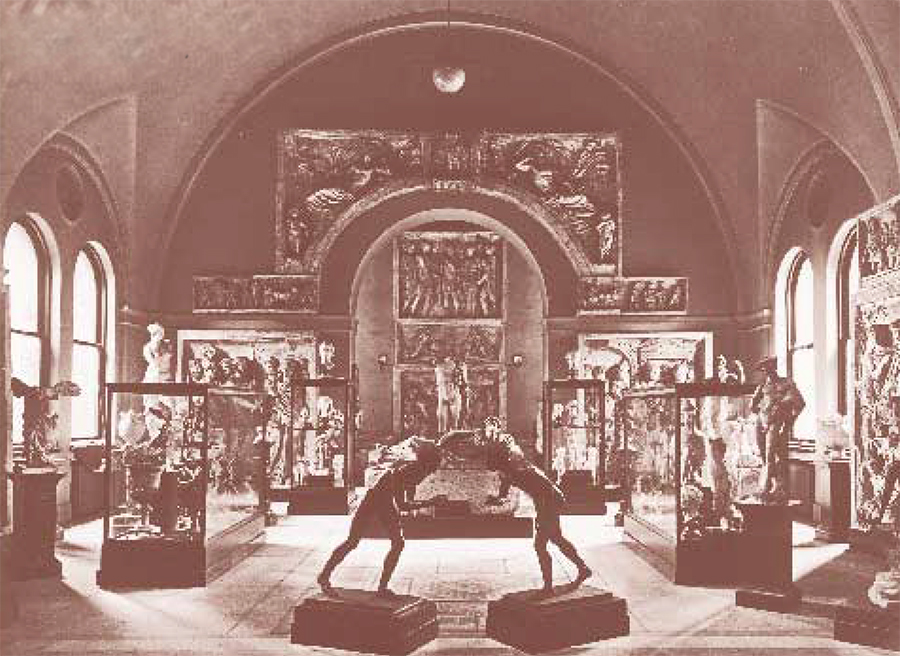

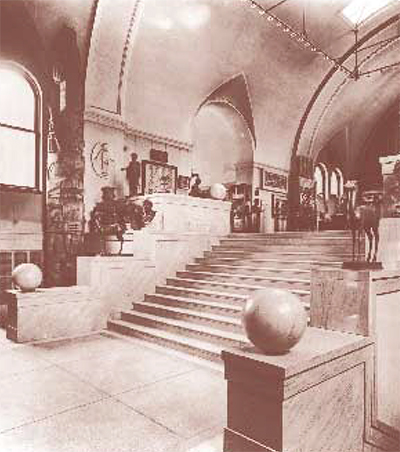

There is a new sense of excitement in the Museum’s Mediterranean Galleries, which are devoted to the cultures of ancient Greece and Italy. It all culminates in spring 2003, when three newly installed and refurbished galleries, the Introductory Gallery, the Kyle M. Phillips, Jr., Gallery, and the Andrew N. Farnese Gallery, join the Ancient Greek World Gallery, reinstalled in 1994, to complete the suite of expansive rooms on the Museum’s third floor. Beyond the fresh and state-of-the-art lighting, visitors will notice a greater variety and number of objects on display, with Greece and Italy. The third-floor galleries formed a chain of domed and barrel-vaulted spaces filled with light, so much light that one of the final orders for the new museum was for 270 window and skylight shades from Gimbel Brothers department store. The original third-floor exhibition scheme reflected late-19th-century notions about the relative importance of the cultures represented there. Historian Steven Conn has argued that the exhibition of these civilizations in the most important galleries was a manifestation of the cultural bias of the Museum ’s planners and administrators. Nevertheless, contemporary conservators will agree that the ethnographic collections were better preserved in the lower, darker galleries. The Greek and Roman sculpture collection — including a number of plaster casts, such as the Roman imperial reliefs from the Arch of Trajan at Benevento — filled Pepper Hall at the top of the wide main marble stairway. Important artifacts that the Museum had recently acquired from excavations in Italy were housed in the gallery between Pepper Hall and the Upper Fitler Pavilion. This installation was named for Phoebe A. Hearst, one of the Mediterranean Section ’s most important early benefactors. In 1904, John Wanamaker, the department store magnate who was also an important early supporter of the Museum, donated a large collection of bronze reproductions of Roman sculpture. Along with several Etruscan stone sarcophagi given by Hearst, these casts transformed Pepper Hall and the stone stair that leads from the Museum ’s main entrance.

At the west end of the building, the Upper Baugh Pavilion and the adjacent gallery housed the collections of the “ Babylonian and General Semitic Section. ” The pavilion was named for Daniel Baugh, who had served as chairman of the building committee and played an important role in securing construction funding. On the east end, the Upper Fitler Pavilion balanced the Upper Baugh Pavilion. Named in honor of former Philadelphia mayor Edwin H. Fitler, the pavilion a more comprehensive interpretation that will better represent the Museum ’s holdings.

The restoration has given the museum an opportunity to turn a reflective gaze on itself. Planners of the new Mediterranean Section wanted to base the redesign on an understanding of how the galleries had grown and changed over the past century. Ideas about museum exhibition and display have changed dramatically since the University of Pennsylvania Museum opened its doors in 1889. Moreover, the backdrop for the exhibits — the Museum itself — is an ever-changing work of art in its own right. The stately building is a physical expression of the ideals of its leaders and benefactors through the years, as well as a functional testament to the vision of its designers. Because these galleries are the result of three separate building campaigns stretching over more than 70 years, they represent a capsule history of the building ’s growth and change. And creating a unified series of galleries out of such diverse architectural expressions proved challenging. Although the final design of the exhibition presents a thematic vision of ancient Greek and Italian cultures that does unify the galleries, the designers decided to exploit their architectural differences rather than ignore them. Restoring the galleries to their original appearance as much as possible became an important component of this project. The resulting plan mirrored the archaeological process, relying on information gathered on site, as well as from historic photographs, to help interpret that physical evidence.

The Original Museum

The oldest part of the Museum was constructed between 1896 and 1899, the work of architects Wilson Eyre, Jr., Cope and Stewardson, and Frank Miles Day and Brother. When the Museum opened in late 1899, the third floor was the main exhibition floor, housing collections from Egypt, the Near East, and ancient Greece and Italy. The third-floor galleries formed a chain of domed and barrel-vaulted spaces filled with light, so much light that one of the final orders for the new museum was for 270 window and skylight shades from Gimbel Brothers department store. The original third-floor exhibition scheme reflected late-19th-century notions about the relative importance of the cultures represented there. Historian Steven Conn has argued that the exhibition of these civilizations in the most important galleries was a manifestation of the cultural bias of the Museum ’s planners and administrators. Nevertheless, contemporary conservators will agree that the ethnographic collections were better preserved in the lower, darker galleries. The Greek and Roman sculpture collection including a number of plaster casts, such as the Roman imperial reliefs from the Arch of Trajan at Benevento filled Pepper Hall at the top of the wide main marble stairway. Important artifacts that the Museum had recently acquired from excavations in Italy were housed in the gallery between Pepper Hall and the Upper Fitler Pavilion. This installation was named for Phoebe A. Hearst, one of the Mediterranean Section ’s most important early benefactors. In 1904, John Wanamaker, the department store magnate who was also an important early supporter of the Museum, donated a large collection of bronze reproductions of Roman sculpture. Along with several Etruscan stone sarcophagi given by Hearst, these casts transformed Pepper Hall and the stone stair that leads from the Museum ’s main entrance.

At the west end of the building, the Upper Baugh Pavilion and the adjacent gallery housed the collections of the “ Babylonian and General Semitic Section. ” The pavilion was named for Daniel Baugh, who had served as chairman of the building committee and played an important role in securing construction funding. On the east end, the Upper Fitler Pavilion balanced the Upper Baugh Pavilion. Named in honor of former Philadelphia mayor Edwin H. Fitler, the pavilion housed the Egyptian collection. All these galleries were furnished with an early form of electric lighting. These unusual fixtures held weak carbon filament bulbs that are a striking feature of many of the early photographs of Museum interiors. Although the Mediterranean Section sculpture was moved from Pepper Hall to the west gallery after the completion of the Harrison Wing in 1915, the collections remained on the upper floor of the 1899 building until the completion of the Administrative Wing in 1929. The collection was then moved to the wing ’s third-floor galleries. In 1958, the Upper Fitler Pavilion was added to the Mediterranean Section ’s gallery space.

The Upper Fitler Pavilion

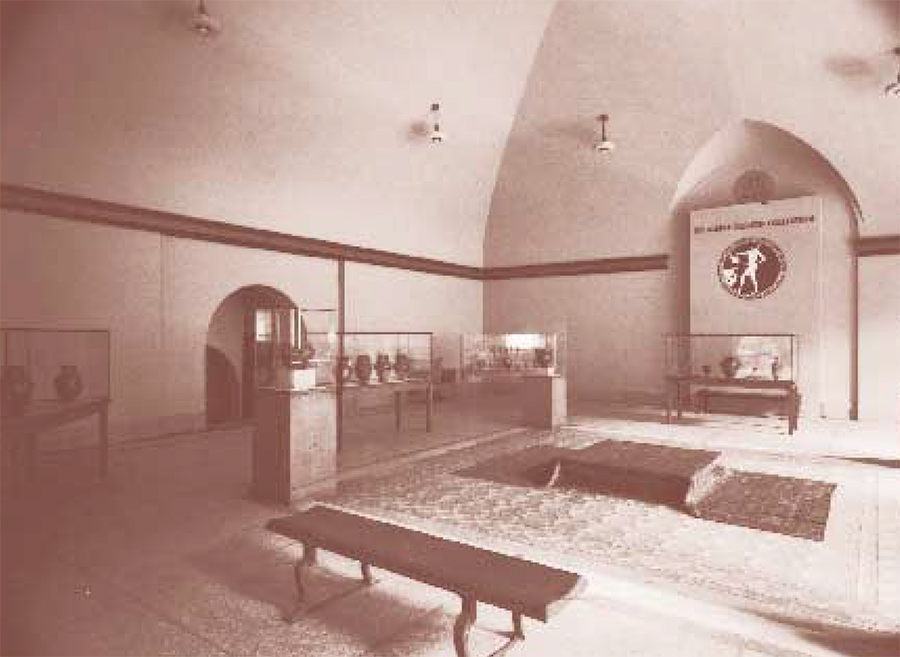

The Egyptian collection was housed in the Upper Fitler Pavilion until 1926, when it was transferred to the newly dedicated Coxe Memorial Egyptian Wing. A vaulted corner pavilion with large windows that faced east and south, the Upper Fitler underwent many changes when the Administrative Wing and its Sharpe Gallery were attached to it between 1927 and 1929. These alterations included rewiring and new lighting, and where the new wing joined the 1899 building, the skylight was partially covered and the east windows sealed. After the completion of the Administrative Wing, the transformed Upper Fitler Pavilion was set up to display various Museum collections, as well as loan exhibitions. Among the installations were Greek vases of the Albert Gallatin Collection, an exhibition on the ancient Maya, and musical instruments of the Sarah Frishmuth Collection. Although the skylight was a major architectural feature of the gallery, it was sealed sometime after 1929 (probably during World War II because of the required blackouts) and finally removed during a reroofing project in the 1980s, leaving only the interior ceiling sash in place. In April 1958, the galleries reopened after undergoing a major rehabilitation and modernization under the direction of G. Roger Edwards, curator, and David Crownover, manager of exhibitions. This was a stylish renovation with a very spare display of objects.

The Upper Fitler Pavilion became a kind of introductor outer court with a display of classical sculpture. It was intended to be seen from a distance and attract visitors to the Sharpe Gallery, which was then, in effect, a dead end. The walls were painted dark blue to set off the white marble sculpture, and the objects were dispersed throughout the gallery with a minimalist aesthetic. In the Sharpe Gallery beyond, objects were displayed in steel-and-glass cases designed in what could be called a combination of international style and Populuxe, reflecting postwar optimism and an attempt to reinvent the museum experience. This modern installation demonstrated that an archaeological exhibition need not be old-fashioned and dowdy. Archaeology and museology, like the rest of the modern world, were about to enter an era of discovery through science and technology. One of the more unusual changes made to the Sharpe Gallery was the modification of its windows. The round-headed windows were partly walled over to make them square, and plaster infills between the marble sills created single uninterrupted strip, giving the windows a streamlined appearance.

The Administrative Wing and The Sharpe Gallery

Archival documentation and a close study of the Administrative Wing and its third-floor Sharpe Gallery reveal a complicated history. The original organizational scheme, in which the third floor served as the main exhibition floor, was maintained while the master plan was built out in three phases between 1915 and 1929. The Harrison Wing, with its Rotunda and Harrrison Auditorium, was completed in 1915. Providing both exhibition and storage space for the Egyptian collections, the Coxe Wing was built between 1924 and 1926. The Rotunda, the Harrison Auditorium, and the Coxe Wing all incorporated the Guastavino vault construction system introduced in the United States in the 1880s. Planning began on the Administrative Wing as soon as construction commenced on Coxe. This new wing was to provide a new entrance, new offices, and galleries that connected back to a new rotunda, larger than the one finished in 1915. The intent of the original master plan was eventually to connect the Fitler Pavilion at its south side to an enormous central rotunda by way of a gallery that helped enclose the entrance courtyard. After preliminary designs for this next phase were prepared in 1924, it was decided to scale back the building program for the time being, so that only the entry court and the wing parallel to South Street would be built. Originally conceived as semicircular, the street-side gallery was straightened out and connected to the Fitler Pavilion ’s east side through an enlarged masonry opening at the site of one of the original windows. The other three windows were filled with hollow terracotta blocks and plastered over Archival documentation and a close study of the Administrative Wing and its third-floor Sharpe Gallery reveal a complicated history. The original organizational scheme, in which the third floor served as the main exhibition floor, was maintained while the master plan was built out in three phases between 1915 and 1929.

The Harrison Wing, with its Rotunda and Harrrison Auditorium, was completed in 1915. Providing both exhibition and storage space for the Egyptian collections, the Coxe Wing was built between 1924 and 1926. The Rotunda, the Harrison Auditorium, and the Coxe Wing all incorporated the Guastavino vault construction system introduced in the United States in the 1880s. Planning began on the Administrative Wing as soon as construction commenced on Coxe. This new wing was to provide a new entrance, new offices, and galleries that connected back to a new rotunda, larger than the one finished in 1915. The intent of the original master plan was eventually to connect the Fitler Pavilion at its south side to an enormous central rotunda by way of a gallery that helped enclose the entrance courtyard. After preliminary designs for this next phase were prepared in 1924, it was decided to scale back the building program for the time being, so that only the entry court and the wing parallel to South Street would be built. Originally conceived as semicircular, the street-side gallery was straightened out and connected to the Fitler Pavilion ’s east side through an enlarged masonry opening at the site of one of the original windows. The other three windows were filled with hollow terracotta blocks and plastered over.

The design program for the spaces in the scaled-down Administrative Wing was always in flux, particularly when building costs had to be reduced. About 40 percent of the aboveground space in the wing was devoted to exhibition. On the south side of each floor, a gallery space, a 14-foot-wide corridor, spanned the length of the Administrative Wing. On the main (third) floor, this gallery was named for Richard and Sally P. Sharpe, parents of two of the donors to the building fund. Over time, the entire addition came to be called the Sharpe Wing. The basement and subbasement were to be used for mechanical systems and storage. The ground (first) floor was to be the main entrance, as conceived in the master plan, and consequently, a large coatroom and rest rooms were included on either side of the entrance. The mezzanine (second) floor contained a central gallery overlooking the main entrance. It was flanked by the boardroom to the east (the present director ’s office) and the executive office suite to the west (the present Nevil Gallery). On the main floor, the space adjacent to the Sharpe Gallery is six steps above the exhibition floor, and the Ancient Greek World gallery and the departmental offices of the Mediterranean Section are located there now. The original intent was to use this area for administrative purposes. Schematic drawings show this space as wide open, undivided, and labeled as “ Studio/Filing Space/Office Space. ”

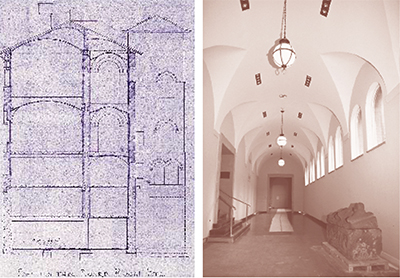

the Architectural Archives, University of Pennsylvania); Right: Eastern view of the Etruscan Gallery in May 2002, with renovations nearly complete

George Byron Gordon, the director, requested that it be left undivided, with the idea that partitions could be added later as the function of the space became more clearly defined. Budgetary constraints probably also played a role in this decision. All the galleries were to have been finished with brick walls and vaulted Guastavino tile ceilings like the Rotunda, the Harrison Auditorium and the Coxe Wing, which was then under construction. This did not happen. Existing documentation of the Administrative Wing reveals two separate sets of drawings, the schematic design set and the actual construction documents. The architects determined building costs on the basis of the schematic design drawings, and they announced in a letter of September 4, 1926, that the project was estimated to be 30 percent over budget. Severe cuts were made to the project before the drawings were completed and sent out to bid. Extensive changes resulted, including reduction of the structural capacity of the floors and the quality of the finishes. The Museum also made many deletions from the plans, such as the subbasement, boardroom paneling, fireplaces, chimneys, light fixtures, operable window sash, elevators, marble borders on the floors, and most of the Guastavino vaults throughout the building. After bids were received, the budget allowed some deleted items to be added back into the project. These included the sub-basement, operable window sash on the north side of the building, and the courtyard with sculpture by Alexander Calder, gates by Samuel Yellin, and modest landscaping. One fireplace and chimney were kept for what was to be the boardroom (now the director ’ s office). The resulting galleries were plaster with canvas coverings and lighted by ordinary “ schoolhouse ” fixtures. The handsome Guastavino vaults were kept only on the first floor and in the third-floor central gallery that would connect to a future rotunda addition. The Mediterranean collections were reinstalled in the 170-foot-long Sharpe Gallery for its opening. The Administrative Wing became, and remains, the home of the Mediterranean Section ’s galleries and offices. The wing had no official opening in the dramatic context of severe cutbacks, Gordon ’s sudden accidental death during construction, and the stock market crash in the autumn of 1929.

The Academic Wing — Elevator Lobby

There was no new construction at the Museum between 1929 and late 1968. Work began on the large Academic Wing in 1968 using designs by the noted firm Mitchell/Giurgola Associates Architects. As part of this construction, a pair of egress stair towers with empty elevator shafts at the back of the Administrative Wing was demolished and the new building was attached at three locations: the east end, where a new fire tower was built; the south side of the central gallery, where a new elevator lobby was added at each floor; and the west end, by way of a bridge at the third- floor level connecting the Roman Gallery with the Upper Egyptian Gallery. The small third-floor elevator lobby is now part of the Mediterranean Section galleries, with both a stair tower and an elevator connected directly to the entrance below. This space is designed to function as the entry point to the new galleries.

Renovation of the Galleries

Developing a restoration scheme for the Sharpe Gallery was complicated by the difference between the original design intent of the architects and the simplified result. In a workable compromise, all the original finishes were restored, but the schoolhouse light fixtures were not replaced. In the Etruscan gallery, we installed modern recessed spotlights in the plaster vault, and salvaged, restored, and hung historic light fixtures from the contemporaneous Coxe Wing. The historic configuration of the windows was also restored. In the central gallery, the Guastavino vault and brick walls were cleaned, and a reproduction of one of the original chandeliers from the Upper Egyptian Gallery was hung. The exposed concrete walls and terracotta tile floor in the Academic Wing elevator lobby were cleaned. In the Roman gallery, the skylight, dark for over 50 years, was reilluminated using artificial lighting. All the original finishes were restored, including the unusual, and important, early terrazzo floor and the unique glass tile floor light. The carbon filament lights could not be restored, but modern track lighting has been positioned in the original locations.

Microscopic paint analysis showed that the original color scheme was a sober gray and white. The walls had been painted many times since 1899, however, so it seemed appropriate to select a color scheme that complements the new installation. In the end, the Etruscan and Roman galleries reinstallation has been a compromise between restoring the original configuration and meeting modern exhibition requirements. The Museum building is itself a three- dimensional archive and thus merits archival preservation. But it is also a dynamic work of architectural art, a poetic expression of the spirit of its founders, leaders, and supporters. As such, the galleries deserve a share of the ardent stewardship dedicated to the objects displayed within their welcoming spaces.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Alessandro Pezzati, Jack Murray, Irene Bald Romano, Donald White, Lynn Makowsky, Francine Sarin, and Jennifer Chiappardi, the University of Pennsylvania Museum; Shawn Evans, Atkin Olshin Lawson-Bell Architects; William Whitaker, the Architectural Archives, the University of Pennsylvania; and Andrew Notarfrancesco, Turner Construction Company. The renovation of the galleries was supported by a generous grant from the William B. Dietrich Foundation.