Historical trade routes across Asia brought together diverse peoples and created markets that were highly cosmopolitan areas of intercultural contact. While individual traders from many different cultures met in these marketplaces, the existence of trading middlemen typically meant that many long-distance trade networks were actually the result of multiple shorter-distance exchanges. Thus commercial goods from one region often traveled farther than the individuals from that region, and the cultural contact between these regions came in the form of exchanged commodities rather than person-to-person interaction.

Examining the everyday household objects traded between sometimes distant communities helps us to gain a new perspective on cultural contact and interaction. This case study of the north Indian region of Ladakh illustrates how trade goods can represent more than just another culture’s reach and influence. They also provide insight into the different cultural perspectives of those involved in the trade and the complex meanings they gave to these commodities.

Where Continents Collide

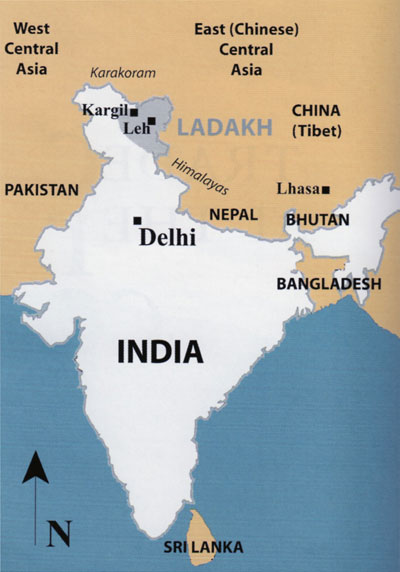

Ladakh is a region most often defined in relation to its surroundings. Perched on India’s northern borders with Pakistan and China, it is situated at the western edge of the Tibetan Plateau, between the Himalayas to the south and the Karakoram mountain range to the north. For some scholars, this defines Ladakh as part of the southern boundary of Central Asia—traditionally divided into Western Central Asia (including today’s Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) and Eastern Central Asia (today’s Xinjiang Province of China). For others Ladakh is the northern boundary of South Asia and the Indian subcontinent, home to Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh. While these high mountains may seem impassible for today’s casual travelers, in the past they did not prevent trade or the spread of culture between regions. Rather, Ladakh was a cultural crossroads in Asia, a conduit for trade and interaction for thousands of years.

The Silk Road And Trade

Overland trade caravan routes were a vital feature of Central Asia, linking East with West, and also connecting regions to the south. Trade in this area was part of what is commonly called the “Silk Road” or “Silk Route.” Karl Haellquist has written in detail about how the Silk Road linked Asia and Europe through an exchange of commodities such as perfumes, drugs, spices, precious stones, metals, cotton, dye-stuffs, coffee, tea, and art objects. This trade first appears in the archaeological record in the 2nd century BCE, and as the demand in the West grew for Chinese silk during the 1st–2nd centuries CE, local populations in Central Asia increasingly became middlemen between empires that stretched from the Roman World to China’s Han Dynasty.

The most vital element to Ladakh’s participation in these South and Central Asian trade routes was its geographic location. Although mountains surround Ladakh, passes through these mountains served as conduits for trade. As a result, the towns of Ladakh became marketplaces where traders from South and Central Asia mingled.

19th And 20th-Century Trade

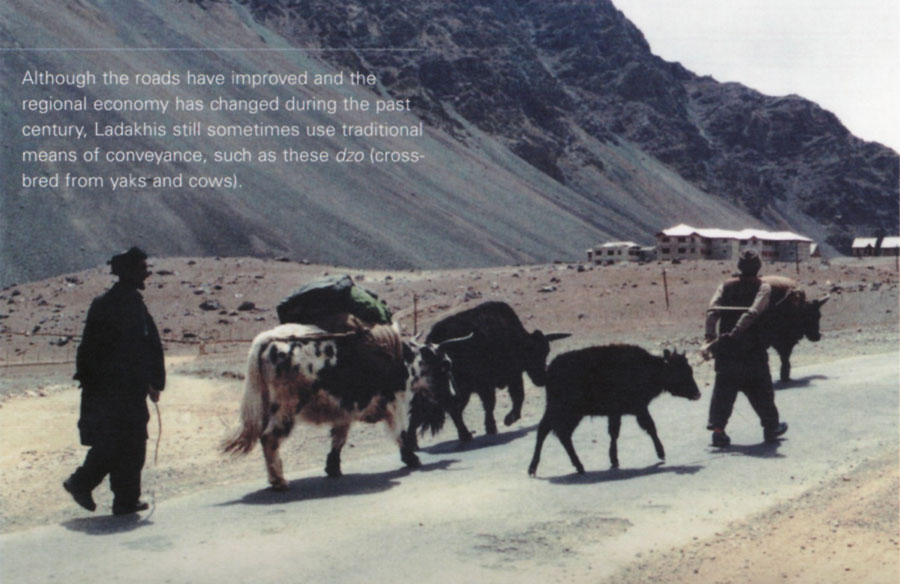

In the early 20th century, three main trade routes passed through Ladakh: the Tibetan route east to the city of Lhasa, the South Asian route south through Kashmir, and the trans-Karakoram route north and east into Chinese Central Asia. Most of these routes were only open for brief periods in the summer, when the snows had melted in the mountains and travelers could traverse the high passes between valleys. Because of the rough terrain, pack-carrying livestock—usually yaks, donkeys, ponies, dzo (crossbred offspring of yaks and cows), and sometimes camels—were the primary mode of transportation.

At the intersection of these trade routes, Ladakh’s main towns of Leh and Kargil housed busy bazaars (market areas), the sites of intense commercial activity where commodities were transported, traded, and taxed. Bazaars were also the zone of cultural interaction. Traders from various parts of Central and South Asia stayed together in caravanserais, the tax and trading posts that also served as inns or hostels for traders during their journey. Thus the traders in Leh bazaar interacted in many activities not directly related to trade, such as sharing meals, telling stories, and praying—interactions that often exposed them to new languages, foods, ideas, and beliefs.

During the late 19th and early 20th century, accounts by visiting Europeans typically described their astonishment at the diversity of the Leh bazaar. For example, in his 1905 travel memoir, adventurer E. F. Knight wrote upon entering the bazaar,

…there is such a motley collection of types and various costumes, and such a babble of different languages, as it would not be easy to find elsewhere…. Leh in September is, indeed, one of the busiest and most crowded of cities, and the storekeepers and farmers who have to supply this multitude must make a very good profit for this time. Leh is therefore a very cosmopolitan city, even in the dead season; for there are resident merchants and others of various races and creeds. Small as is the permanent population, at least four languages are in common use here—Hindostani, Tibetan, Turki, and Kashmiri— while several others are spoken.

This scene would have been common in most of the cities along the Central Asian trade routes at this time.

Participation in trade helped to shape all aspects of Ladakhi culture. We see this demonstrated most clearly in Ladakh’s diverse population. Buddhist and Muslim communities form the majority, challenging modern visitors’ notions of a homogenous Indian Hindu culture. In the past, as traders, Ladakhis were in contact with people from many different regions, and as a result, they often spoke a variety of languages, earned wages in a variety of international currencies, and were active consumers of cosmopolitan trade goods for centuries.

Trade, Commodities, And Culture

The commodities brought by traders to Ladakh during the early 20th century indicate cultural influences from afar. The most high-profile artifacts of this trade are the fine carpets and exquisitely wrought household objects of silver and gold brought to Ladakh by Central Asian traders. Many of these goods are still on display in the homes of the descendants of Ladakhi traders and are highly sought after by those interested in antiques. These items, however, are only a few examples of the many luxury goods traded in Ladakh, and they represent only a small fraction of the goods traded.

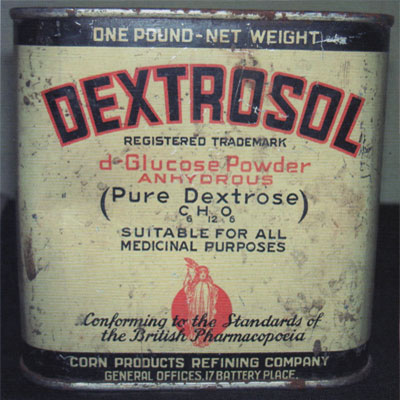

A review of trade goods from the early 20th century shows a significant portion of everyday items manufactured in Europe, Japan, and the United States. Most of this foreign merchandise came through Ladakh on its way to Central Asia from British colonial South Asia; only a few came the other way, through Central Asia to Ladakh. In particular, common household goods, such as kitchen utensils, textiles, jewelry, medicines, and toiletry items, were brought from South Asia to Ladakh for trade to Chinese Central Asia because their high resale value made the long trip profitable for trade middlemen.

These seemingly pedestrian items can provide key information about the spread of ideas and innovations. They also can provide insight into how the meaning of objects can change in different contexts, and how, in turn, those meanings can change the wider world. The trade in British and Japanese cotton textiles provides a good example.

In the mid-19th century, the British textile industry, using modern technology, symbolized Britain’s national strength and provided the revenue to fund further British advances in industrial technology. By the end of the century, Britain had the largest textile export industry in the world, and India was the largest importer. In contrast, mid-19th century Japan had neither a very large domestic cotton manufacturing system nor a large export market. Yet, in the early 20th century, when the Japanese began to export cotton goods to Asia, Japanese goods gained popularity in India in spite of protective tariffs which favored equivalent British goods.

This shift in Indian consumption from British to Japanese cotton goods was the result of a social movement in local Indian markets that formed part of the Indian struggle for independence. One of the keystones of Gandhi’s fight for independence was a boycott of British textiles in favor of khadi, an Indian fabric of handspun thread. For related reasons, Japanese-manufactured cloth appealed to Indian consumers. In Ladakh, account books from this time record a growth in sales of cotton piece goods manufactured in Japan. This should not be surprising since Japanese goods were often marketed with Indian nationalist concerns in mind, using Hindi names to appeal to public sentiment.

This acceptance of Japanese cotton cloth goods in reaction to the wider political struggle against colonialism had important repercussions in both England and Japan. By the 1930s a significant portion of Japan’s export trade involved textiles and textile-producing machinery. This helped to launch Japan as a major global exporter of consumer goods at the same time that British textile exports declined. By challenging British notions of technological and industrial superiority and opting instead for Japanese alternatives, traders, such as those in Ladakh, helped India’s resistance to colonialism and helped to make Japan into a world-wide export power. Thus, traders in Ladakh were not only merchants of commodities; they were also the purveyors of goods that had meanings which interacted with local social movements to influence global events.

A Legacy Of Trade

Historical trade commodities are not simply representations of past cultural contact. They also had meaning to those who produced them and those who sought to obtain them, and the nature of this meaning can be debated long after their trade ceased. For example, large bronze plates made in Chinese Central Asia during the early 20th century are still treasured by Ladakhi families today. In addition to their association with a high socio-economic status, many of my informants explained that their Central Asian ancestors brought these platters to Ladakh to reinforce their ethnic identity as Yarkendis, Turkic peoples of Chinese Central Asia. In contrast, many Ladakhi Muslims feel that such plates, which are used during special events to eat shared meals, represent a sense of belonging to a larger Islamic community where an ideology of equality persists. Thus, such artifacts simultaneously display historic contact between groups, represent past notions of ethnic identity, and reinforce present-day notions of social cohesion.

Each of the trade goods shown here have their own stories and they provide different perspectives on cultural connections and change. They help us understand how culture contact occurs through both the movement of peoples and commodities, and they help us consider the relationships between those who made the goods, those who traded them, and those who obtained them—diverse peoples who may never have actually met. These artifacts of trade and their use show us that goods can become symbols of relationships between communities. Buyers of commodities in the past were not simply consuming the foreign meanings associated with these foreign products. British cloth did not have the same meaning in Ladakh that it had when it was produced in a mill in England. Rather, the participants in trade networks create their own local meanings for the goods they trade, meanings that can, in turn, change over time.

To understand these meanings and the social role that these objects played (and play) within communities, anthropologists must examine the ways in which commodities interact with systems of traditional meaning. These foreign goods were not just inanimate interlopers; they were the means by which traditional social relations were articulated, defined, and challenged over time, as they are today.

Bray, John, ed. Ladakhi Histories: Local and Regional Perspectives, Tibetan Studies Library. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2005.

Haellquist, Karl R., ed. Asian Trade Routes: Continental and Maritime. London: Curzon, 1991.

Knight, E. F. Where Three Empires Meet: A Narrative of Recent Travel in Kashmir, Western Tibet, Gilgit and the Adjoining Countries. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1905.

Markovits, Claude. The Global World of Indian Merchants 1750–1947: Traders of Sind from Bukhara to Panama. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Rizvi, Janet. Trans-Himalayan Carvans. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Snellgrove, David L., and Tadeusz Skorupski. The Cultural Heritage of Ladakh. Forest Grove, OR: Aris & Phillips, 1977.