Beginning in 1950 stories of a large collection of strange ancient figurines surfaced in the American and Mexican press. Waldemar Julsrud, a German shopkeeper living in Acámbaro, Guanajuato, Mexico, had purchased from local excavators more than 33,000 clay figurines made by a previously unknown culture. Most astonishing, however, was that the figurines included representations of dinosaurs eating humans, humans riding dinosaurs, and other examples of humans and dinosaurs together.

Although professional Mexican archaeologists immediately pronounced these artifacts to be fakes, observers outside the archaeological community were intrigued, and a number of popular articles soon appeared questioning the “dogmatic” views of establishment archaeologists. Maybe dinosaurs and humans had coexisted at some point in the past, or maybe dinosaurs had become extinct much later than 65 million years ago. The sheer number of figurines seemed to make the possibility of faking them remote, unless an entire crew of villagers was involved. Also, if the aim was to hoodwink foreigners into buying fakes, one would expect the artifacts to resemble known types. Why fake such outlandish figures? Moreover, how did illiterate peasants in a remote Mexican town know about dinosaurs in the first place? But if the figurines were really based on actual dinosaurs, why had no dinosaur fossils been found in the Acámbaro region, and why had no other Mexican cultures recorded any dinosaurs?

In 1952, Charles DiPeso (or Di Peso), an archaeologist affiliated with the Amerind Foundation in Arizona, visited Acámbaro, studied Julsrud’s collection, and observed two excavators at work. He concluded that the figurines were indeed fakes: their surfaces displayed no signs of age; no dirt was packed into their crevices; and though some figurines were broken, no pieces were missing and no broken surfaces were worn. Furthermore, the excavation’s stratigraphy clearly showed that the artifacts were placed in a recently dug hole filled with a mixture of the surrounding archaeological layers. DiPeso also learned that a local family had been making and selling these figurines to Julsrud for a peso apiece since 1944, presumably inspired by films shown at Acámbaro’s cinema, locally available comic books and newspapers, and accessible day trips to Mexico City’s Museo Nacional. Even this study, published in American Antiquity, however, failed to convince those who argued that the figurines were genuine.

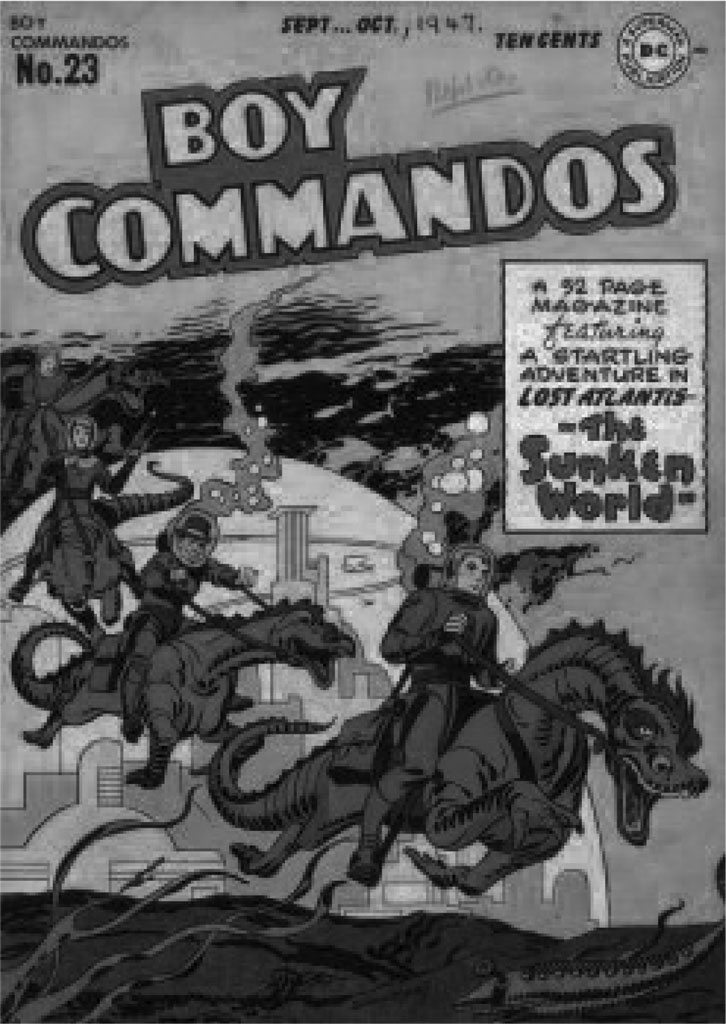

In 1955, Arthur M. Young—an engineer and inventor who had created the first civilian helicopter in 1946 and later founded the Institute for the Study of Consciousness—asked then Museum Director Froelich Rainey to look into the matter. Rainey, never shy to examine controversial subjects, agreed. It fell upon Linton Satterthwaite, Curator of the American Section, to prepare a Museum exhibit during the winter of 1955–56 that illustrated both sides of the debate. “Genuine Ancient or Comic Book Art?” featured pieces from the Julsrud collection juxtaposed with drawings from comic books that were thought to have inspired them.

Between 1969 and 1972 the Museum’s Applied Science Center for Archaeology (MASCA) reignited the debate when it tried to date some of the figurines using a relatively new technique known as Thermoluminescence, or TL dating. The results produced a date around 2500 BC, and Rainey eagerly proclaimed it to be correct, much to the chagrin of other archaeologists. However, when additional TL analyses were conducted in 1978, it became clear that the TL technique employed in MASCA was unable to read the artifacts’ true thermoluminescence. Instead, artificially old dates were seemingly being produced by calculating the figurines’ chemiluminescence, a different phenomenon which cannot be used for dating. As a result, serious doubts were raised about the accuracy of the earlier dates. Thus the best interpretation of the figurines, once again, was that they were modern fakes.

Today, Waldemar Julsrud’s collection is on display in its own museum in Acámbaro, and the Internet continues to provide accounts from those who believe in its authenticity.