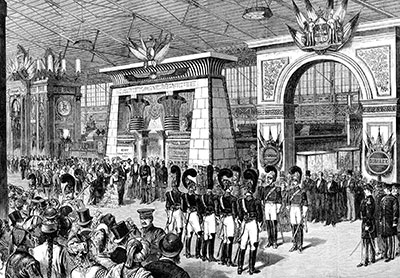

of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as The Crystal Palace Exhibition, London 1851.

In 1876, the President of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant, and the reigning Emperor of Brazil, Dom Pedro II, turned cranks that set into motion the world’s largest steam engine at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. The Corliss engine— at 1400 horsepower and towering 40 feet over the heads of the opening ceremony crowds— drove hundreds of steam-powered devices in Machinery Hall at the world’s fair celebrating the 100th anniversary of American independence. Nine million visitors, 37 nations, 24 U.S. states and territories, and countless commercial interests celebrated the progress of the nation.

Like other international exhibitions in the late 19th and early 20th century, the Centennial Exhibition was designed as a place where all the commercial, colonial, and industrial accomplishments of the world’s “advanced” nations could be classified, displayed, and most importantly, compared. American ingenuity and manufacturing prowess were being tested at the Centennial, and the Corliss engine was proof that the United States could hold its own against the established powers of the Old World.

World’s fairs were marvelous meetings of different peoples, cultures, foods, artifacts, and technologies, and they fascinated the world for more than a century. Starting with the 1851 Great Exhibition in London, these fairs were like miniaturized trips around the world: the cosmos compressed into a well-designed space. Competition to host a major world’s fair was fierce, and the stakes were high both economically and in terms of prestige: for a brief time, the host city was the most important place in the world.

If we remember that these gatherings of the world’s citizens were a combination of varied interests and pursuits, then they can seem quite remarkable and modern. At any one fair you could smoke a Turkish pipe, witness new inventions like the telephone, learn the dangers of hookworm, view archaeological artifacts from Peru, cast an eye on nude art, taste root beer, see gems from Tiffany, and marvel at models of some of the world’s wonders including Niagara Falls and the Panama Canal.

The fairs provided an opportunity to share information, survey others, make declarations of identity, and exchange material culture. In an era without electronic media, they were the Internet of their day, an impressive form of mass communication not only for the actual visitors but also for the millions more who read about the exhibits in newspapers and magazines. e goal of this mass communication included instructing citizens on the values, priorities, and accomplishments of their home nation and defining their nation’s place in the order of the world.

Like a comprehensive picture encyclopedia, the fairs were thought to educate the masses through observation and experience. The 1901 fair in Buffalo was described as a “colossal university” and the 1904 exposition in St. Louis was the “University of the Future,” educating visitors about the changing world. Most exhibitions also sponsored academic and professional congresses that ad- dressed significant contemporary research and social issues.

World’s Fairs Referenced in This Issue

The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, or the Great Exhibition, or The Crystal Palace Exhibition 1876, Philadelphia: Centennial Exhibition, or The Centennial

1889, Paris:

Exposition Universelle

Exposición Histórico-Americana, or the Columbian Historical Exposition

1893, Chicago:

World’s Columbian Exposition or Chicago World’s Fair

1895, Atlanta:

Cotton States and International Exposition

International Central American Exposition

1900, Paris:

Exposition Universelle, or the Paris World’s Fair

1901, Buffalo:

Pan-American Exposition

1904, St. Louis:

Louisiana Purchase Exposition, or St. Louis World’s Fair

Panama-Pacific International Exposition

1915, San Diego:

Panama-California Exposition, or San Diego World’s Fair

1964–1965, New York City:

New York World’s Fair

2010, Shanghai:

Shanghai Expo

Creating an Ordered World

Looking back, some critics of the expositions have claimed that the fairs were strictly commercial, designed to promote the exchange of goods, or that they served primarily to reinforce colonialism and governmental power. The fairs certainly promoted the idea that more “advanced” humans should be in control of the planet and its resources and people. But an anthropological eye on the fairs suggests a much more dynamic and wide-ranging effect on American culture. Thinking of the fairs as a form of world-building rather than just as oppressive economic or political events opens up a more vital discussion of their appeal and influence.

Order and categorization were the rule at these international rituals, not only to keep the crowds in check and the goods protected, but also to present an image of a world order that could be carried back to various homelands. The fairs were designed to state how and why the contemporary industrialized world existed and what was needed to keep it functioning smoothly and efficiently.

At the 1876 Philadelphia Exhibition, a committee was tasked with creating exhibit categories in order to carry out this mandate. They developed ten classifications that showed an evolutionary development from raw materials to intellectual accomplishments. A system of awards was designed to acknowledge quality in each class and Centennial medals were useful in later advertisements by the winning companies.

Each fair added and subtracted departments and categories, but all followed the same agenda of world-building through the organization of their exhibits. Basic subdivisions of many fairs included mining, manufacturing, agriculture, horticulture, education, and art as well as exhibits that addressed human evolution, both physical and social.

Dr. Frederick J.V. Skiff, who helped design several American fairs and American exhibits at foreign fairs, called the classification system the “Bible” of any fair because it took the proposed displays and “[gave] their importance in the scheme of life.” He designed American exhibits that taught audiences about progress. Exhibits often traveled from one fair to another, and most of the international fairs were organized in the same way with visitors expecting certain features that helped perpetuate the same world order.

Anthropology and Living Ethnological Displays

At the same time that these world’s fairs were working to define a world order, the discipline of anthropology was organizing itself as a respected academic field. Anthropologists at these early fairs contributed to a model of social evolution in which the more advanced civilizations had the right and duty to control and use the uncivilized peoples and their resources. The exhibits of mined and manufactured goods and equipment at every fair celebrated these advancements but failed to acknowledge that the raw material and labor for those marvels were firmly embedded in colonial policies. The developing discipline of anthropology did little to combat this approach and in some ways helped promote it.

The overarching theme of all of the fairs was progress, and anthropology provided an evolutionary scheme to vividly demonstrate this. Using the idea that every society went through the same stages of development, fair anthropologists promoted a classification scheme for societies that was simple and easy to understand and made them seem like experts on the rapidly changing world.

Although there were some anthropologists who fought this evolutionary model, it became accepted wisdom by the turn of the 20th century that all human societies progressed from barbarism to civilization, from the primitive to the modern, and that this evolution was necessary and inevitable. This line of thinking was demonstrated at many of the fairs through living ethnological exhibits that displayed non-Western people as missing links and as relics of past evolutionary stages.

The display of live “exotic” or “primitive” people at the fairs took place in both official exhibits and in sideshows. These sideshows were later incorporated into the fairgrounds, and the difference between official representations and pure entertainment was soon blurred. At the 1876 Centennial Exhibition, Native Americans were represented by displays of artifacts because Congress would not allocate money for living displays. Some Native Americans did, however, set up

an encampment on the Centennial grounds, supposedly demonstrating the “mode of life” of the original inhabitants of the country. The reality of the Native American situation in the west intruded on the fair with the news in June 1876 of General George Custer’s defeat and death as he battled a coalition of Indian tribes. The newspapers of the time, alongside their reporting on the Centennial, celebrated Custer and condemned the “savages” who killed him.

Philadelphia hosted the first fair to have an extensive sideshow right outside its main gate. “Shantytown” was a mile long counter-fair consisting of beer gardens, cheap hotels, freak shows, peanut vendors, foreign restaurants, and carny games (where you could win a photograph of Custer). A “museum” had fake displays of primitives including the “Wild Men of Borneo” and the “Feejees” who were cannibals.

The officially sanctioned and more extensive concessionaire displays of indigenous peoples, both real and imagined, came in subsequent fairs. By the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, ethnological displays were not allowed to spring up spontaneously: in Chicago they were controlled by the anthropologists. Inside the Chicago fairgrounds, the Ethnology Department was housed in its own building and contained prehistoric habitations, monuments, and artifacts illustrating the “progress of nations.” There was also a reproduction of an Indian school with children demonstrating their industries and crafts.

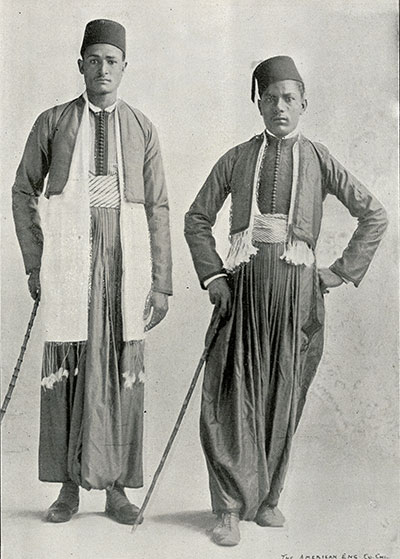

The exhibits of living people were assigned to “The Midway Plaisance” which was also controlled by the Department of Ethnology. People from the South Seas, Algiers, Java, Samoa, Brazil, and other places lived in vil- lages that the fair catalog described as “tenanted by living representatives of savage, civilized, and semi-civilized nations” forming a “bazaar of all nations” alongside panorama displays, food outlets, exotic dancers, and the world’s first Ferris wheel. Not permitted on the Midway proper, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show with Indians and Cowboys (re-enacting Custer’s last battle) played to large audiences nearby.

At the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, the Foreign Villages were considered “odd, novel and spicy” attractions on the midway, consistent with the “Progress of Man” theme of the rest of the fair. e Africans who were shown in a stereotypical “Darkest Africa” exhibit as primitive and wild men, were, however, billed as an educational ethnological exhibit.

At the 1904 St. Louis Fair, the Anthropology Villages and an adjacent Indian Village housed hundreds of people who were supposed to represent their traditional culture with old-style housing, dress, ceremonies, and crafts. Each culture was separated by a fence but seemed to blend into each other in a continuous line of evolutionary order from African to Native American, from dark to less dark. A visitor could see 29 examples of the primitive world all in one place, a visual example of the masses of uncivilized at the bottom of a pyramid that had Western Europe and America at its pinnacle.

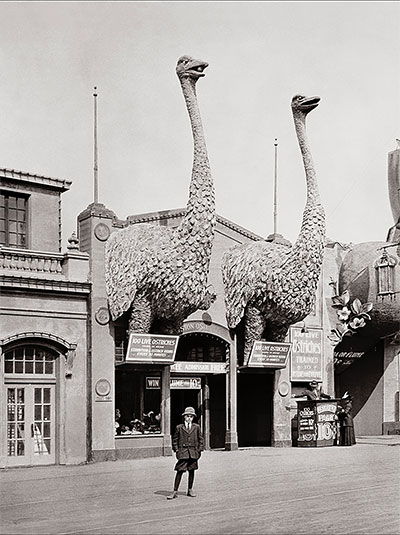

The 1915 San Francisco Fair no longer had a separate anthropology department that showed static Native American exhibits, but live Indians inhabited a wild west show and a faux Hopi village in the midway. A musical called “The Death of Custer” was staged with 300 musicians and 50 Indians who contributed the sounds of their battle. The midway also featured a Hawaiian show with hula-hula dancers; a Samoan exhibit; Chinese, Irish, and Japanese Villages; ostrich rides; and a tug of war between Hawaiians, Samoans, Filipinos, and Maoris during a special carnival. Most popular was the Tehuantepec Village with real Mexicans.

At the rival 1915 fair in San Diego, anthropologists emphasized the evolution of the races through physical anthropology and archaeology displays. The midway concessions included a Hawaiian Village and Japanese Streets as well as a life-size replica of a pueblo. Material and people from New Mexico provided the authenticity the fair organizers desired. Native American weavers, silversmiths, potters, and basket makers practiced their crafts using traditional techniques. The exhibit was sponsored by the Santa Fe Railroad, which hoped to attract people to visit the real Indian villages along their train route.

When it came to displaying colonized people, world’s fair anthropologists helped to define them as exotic “others” who still performed primitive rituals, ate bizarre foods, wore strange clothes, made everything by hand, and provided a stark contrast to advanced nations. The native villages placed all native people in the same evolutionary past, separated from the advanced nations by their backward ways and by an inability to cross over to the future.

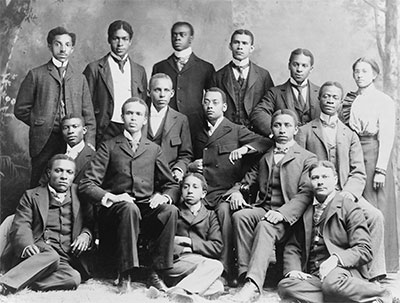

Invisible African Americans

If indigenous peoples of the world were denigrated or romanticized through their official and concessionnaire exhibits, at least they were recognized as existing. For African Americans, near invisibility at the early fairs was a vivid statement of their tenuous and ambiguous posi- tion in American culture. The 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia took place only 11 years after the end of the Civil War and only a life-sized statue called “The Freed Slave” acknowledged the war’s cause. A “Restaurant of the South” near the U.S. government building even featured a “Darky Band.” Similar “Old Plantation” concessions, recreating happy, singing, carefree slaves, appeared at numerous later fairs.

A pamphlet addressing this situation was published during the 1893 Chicago Fair. In “The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in The World’s Columbian Exposition,” Frederick Douglass explained that the fair had welcomed native people from around the world but not its own freed slave who is still seen as a “repulsive savage.”

Women’s Roles at the Fairs

Women’s activities at the fairs varied. The great-grand-daughter of Benjamin Franklin, Elizabeth Duane Gillespie, raised $30,000 to cover the cost of building a Women’s Pavilion in Philadelphia in 1876, the first of its kind at a fair. The Women’s Pavilion exhibits featured paintings and sculptures, patented inventions, photographs of charity work, carved wood furniture, needlework, medical displays, and other products of the labor of women. It was also a place where activists from across the country met. The women’s committee in Chicago in 1893 arranged for an anthropological exhibit called “Woman’s Work in Savagery” to show woman’s progress from the earlier work of “primitive” and “semi-savage” women. They also organized the “World’s Congress of Representative Women of All Lands,” a series of public talks about women’s issues that was attended by 150,000 people.

But at St. Louis in 1904 and San Francisco in 1915, the women’s committees thought women should focus on being the official hostesses. They also thought that “indecent or improper” concessions (referring to the midway displays) should be banned. Suffragists and other women activists did have a presence at many of the fairs, but the fairs presented conflicting and contradictory messages about women’s place in the world.

Legacy of the World’s Fairs

World’s fairs inspired generations of entrepreneurs, artists, inventors, writers, scientists, designers, architects, and everyday citizens. The fairs displayed inventions that changed the world, created transportation that united nations, sold ideas that promoted commerce, and influenced the perception of indigenous people. Wonders and marvels never before witnessed— from popcorn balls, Cream of Wheat, and bananas to the electric light bulb and the diesel engine— delighted the consuming audiences. International exhibitions generated numerous museums that obtained artifacts from the national exhibits or from scientific expeditions associated with the fairs (see Xiuqin Zhou, this issue). The discipline of anthropology was introduced to the public through exhibits about race and indigenous people and through evolutionary schemas for the exhibits.

To us today, world’s fairs may seem quaint or outdated. The idea of the globe’s nations gathering together in peaceful co-existence and cooperation for months might even seem utopian. Yet world expositions are still planned every five years. This seems to point to a long-standing human quest to connect with or at least garner a glimpse of other people, other worlds, and other possibilities.

LOUISE KRASNIEWICZ is Adjunct Faculty in the Department of Anthropology at Penn. During the Spring 2015 semester she taught Anthropology & World’s Fairs.