Observing a skilled artisan at work brings to the viewer an understanding that is bath aesthetic and intellectual, and that is absorbed through avenues other than words. It is the way apprentices around the world have traditionally learned their crafts. For scholars, the study of material culture is enhanced enormously by direct observation. It can yield information on many aspects of technology, from the technical and material to the social and cultural, about which the artisans themselves may not be aware or be able to verbalize. Observing work in progress may lead to questions that otherwise might not have been asked, and broadens the range of possibilities to be considered by archaeologists reconstructing past craft activities and organizations.

Those who study the past do not have the advantage of being able to observe ancient artisans at work and to question them about what they did and why they did it and how their crafts fit into the rest of their lives. These scholars can, however, look at how similar crafts are being pursued today, and use that information to help them assess what they find from the past or to augment their general understanding of craft activities and their role in society.

Western scholars today are generally shut off from this way of learning on their home ground. In the United States, for example, handmade items tend to be imported rather than made domestically; even in rural areas the traditional potter, the basket maker, the weaver, or the blacksmith is no longer a common part of everyday life. Among the shrinking number of places where pottery making and metal working still remain viable ways of making a living, India has attracted much academic (and popular) attention. The studies in the following special section are three examples of this recent interest in Indian crafts and craftspersons. All entailed direct observation of artisans, from the four corners of India, who in their homeland are makers of both ritual and utilitarian objects in terracotta and in metal.

The approaches used in the three studies are not all the same, however. While all of the authors are archaeologists by training, Reedy is also an art historian concerned with finding ways of resolving some of the unknowns presented by unprovenienced medieval statues in museum collections. Beaudry, Kenoyer, and Wright are archaeologists who have a special interest in the study of pottery, which for its abundance, preservation, and interpretive utility is the archaeological artifact par excellence. Horne works more directly in the present, concentrating on contemporary craft production and the role of specialists in a changing society.

Significantly, these three studies are all museum-based. Two originated in public programs and documentation, the third in the study of museum collections. It is becoming apparent from projects like those described here that museums of art, archaeology, or ethnography benefit greatly from adding an ethnographic component to the more traditional static display or public lecture upon which the dissemination of information has depended in the past.

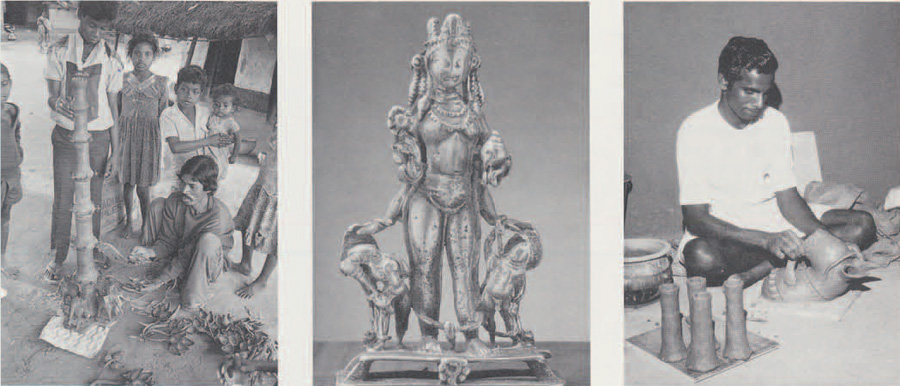

(Middle) An 8th-9th century A.D. bronze statue from India made by lost wax castering. See Article by Reedy.

(Right) The potter M. Palaniappan at work. See article by Beaudry, Kenoyer, and Wright.