In 1891, a small sketchbook with thirty-one drawings entered the collection of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (then the Free Museum of Science and Art). The book was purchased from Matches, a young Southern Cheyenne man at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida, sometime between 1875 and 1877. Matches was part of a group of seventy-two Native Americans who had been brought as prisoners of war to Fort Marion. While incarcerated, most of the prisoners created drawings (generically known as “ledger drawings”), as generations of warriors on the Plains had done before them, with some traditional scenes of battles and raids, but here tempered with quieter imagery of camp life and hunting.

Each work of art, every piece of material culture, is a historic document, no less important because it is visual rather than written. Each reflects the society, the time and the place of its creation, encoding within itself multiple histories. Matches’s sketchbook is no exception. It contains within it the histories of the demise of traditional high Plains culture, the change of an art tradition, the beginnings of a new tourist culture, the genesis of a Native American educational enterprise: a multiplicity of histories, both native and non-native, linked and intertwined.

The End of the Southern Plains Wars

With the end of the Civil War in 1865, the United States was able to commit a large number of well-trained and battle-seasoned troops, along with the most technologically advanced weaponry, to the implementation of the doctrine of Manifest Destiny. It was in the twenty-five years between 1865 and 1890 (Wounded Knee) — which saw the opening of the transcontinental railroads, decimation of the bison herds, and confinement of nomadic hunters/warriors to reservations — that the final struggle between Native Americans and the U.S. government for control of the west was played out. On the Southern Plains in Texas and Oklahoma, this struggle culminated in the Red River War (also called the Buffalo War, 1874-1875), a last and desperate attempt by the Arapaho, Southern Cheyenne, Comanche, and Kiowa, with their force of seven hundred warriors, to resist the end of their nomadic existence.

After their defeat in 1875, in order to insure the compliance of the native population on the reservations, seventy-two prisoners were selected to be taken to Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida, where they were to remain prisoners of war for three years until 1878. Although there were a few noted leaders among the prisoners, the majority were young men, who, in the traditional life-style of the Plains, would have been just beginning their careers as warriors.

Captain Richard Henry Pratt was the army officer charged with the care of the prisoners of war. He accompanied them from Fort Sill, Oklahoma, to Fort Marion, a journey that took twenty-four days. During their three-year captivity, the prisoners were taught to read and write. They also worked at various jobs that allowed them to earn money, in addition to acquiring new skills. Another source of income for them was the creation of drawings as souvenirs for the burgeoning tourist trade that was making the area around Jacksonville and St. Augustine a prime vacation spot in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Drawing and painting, an activity engaged in by almost every warrior, had a long history on the Plains.

The Tradition of Plains Warrior Drawing

Among the peoples of the Plains, the tradition of painting and drawing had two major divisions: geometric and figurative. Geometric work was the province of women; figurative painting was done by men. Figurative painting was further divided into symbolic and representational aspects. “Symbolic” paintings were those that had their genesis in dreams or visions. Items decorated with visionary painting included shields and lodge (tipi) covers. Within “representational” figurative painting, two other threads can be discerned: calendric records and heraldic painting. Both were based on a system of pictographic signs that functioned as a visual shorthand across the Plains. Galendric records were represented by winter counts that were mnemonic devices in which a single drawing represented a single year. This sequential series of drawings allowed the band historian to recount the history of his people. Heraldic painting was primarily autobiographical, its purpose being the recording of a warrior’s brave deeds in warfare and raiding, those activities by which a male gained prestige and accumulated power. By painting his buffalo robe in this manner, the warrior made the most public display of his accomplishments every time the robe was worn.

The history of figurative painting on the Plains began with the early incised and painted petroglyphs found throughout the region, predating European contact. This same style of figurative drawing appears on the earliest buffalo robes extant, those from the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries that are preserved in museums. Human and animal figures were rendered with an economy of means: circular heads with no facial features, elongated triangular bodies, stick arms and legs. Other pictographic conventions were also employed in order to show, among other things, movement and speech. Around the mid-nineteenth century, painted buffalo hides begin to exhibit a more naturalistic handling of subject matter, including a delicacy of line, a broader range of body movement, and the addition of more detail. This may have occurred partially because of wider exposure to Euro-American art and artists: artist/travel Mrs on the Plains, as well as books and prints, brought in with the flood of new immigrants. With the introduction of new media (muslin, paper, pencils, brushes, paints), in the last half of the nineteenth century, the warrior artists of the Plains achieved new heights in drawing and painting which culminated in the what is termed “ledger art”. This was because some of the first drawings in this very detailed manner were done on the ruled and lined pages of ledger books. ( In fact, the artists utilized whatever paper was at hand.) The range of subject matter also increased during this time: scenes of camp life, depictions of dances, courting scenes, and hunting scenes, were given as much place as the traditional depictions of battles and raids which were fast becoming activities of the past. What had been a very public art form now became a very private and personal one, contained within closed books, not worn as a robe for all of the world to see.

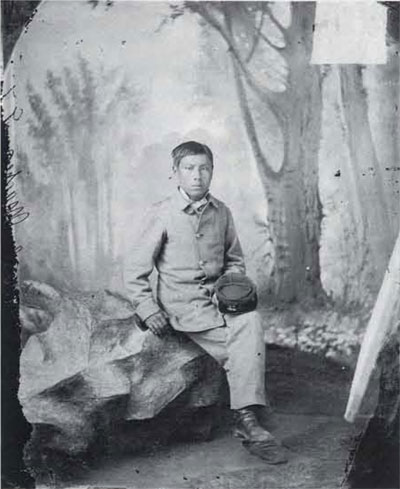

Matches

Matches [fig. I] was one of thirty-two Southern Cheyenne warriors arrested on April 3, 1875, at the Cheyenne Agency in Indian Territory (Oklahoma). At the time of his arrest he was nineteen years old, according to Captain Pratt’s lists, although there are some discrepancies with other lists that suggest Matches was older when he was arrested, perhaps as old as twenty-five. His mother was listed as being the only one alive of all of his immediate family. His parents were Gunim and Coming in Night. Matches, whose Cheyenne name was Chis-I-Se-Duh, was probably a member of either the Bowstring Society or the Dog Soldier Society (two of six warrior societies among the Southern Cheyenne). Upon his arrest he was listed as a “ringleader’, as were many of the other young men, but no charge was listed against him. As Captain Pratt commented in a letter from Fort Sill on April 26, 1875, “Most of the younger men have simply been following their leaders, much as a soldier obeys his officers, and are not really so culpable?’

After the three year imprisonment at Fort Marion ended, twenty-two of the former prisoners chose to stay in the East to participate in Captain Henry Pratt’s experiment in Native American education, which culminated in the opening of the Carlisle Indian School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania in 1879. Pratt wrote in a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs (April 23, 1878) that their remaining “…is entirely of their own choosing…” Matches was among fifteen who, in April of 1878, went to Hampton Institute in Virginia, an educational institution established after the Civil War to educate newly freed African-Americans. Preserved in Captain Pratt’s papers is a short speech delivered by Matches given a month after his arrival at Hampton: “I go school — way off. I come a school — three days, way off — sea. I go school here — l like school here. Came not here — other house. I went school — Miss Mather. I like here—all these girls — good gills”. Matches (his native name now listed as Nan-Hi-Yurs) remained at Hampton until June 1879 when he departed for the Carlisle Indian School where he became known as Carl Matches. There is a short statement by Matches in the school news dated 1882 where he describes the type of agricultural work in which he was involved. Training in agriculture and farming was a major focus at Carlisle, in addition to blacksmithing, woodworking, and carpentry; all trades deemed productive, civilized, and therefore necessary for the advancement of Native Americans.

Matches returned to the Cheyenne Agency in 1892 and took his allotment of land (allotment no. 583) around the Canton and Watonga areas, where most of the Bowstring and Dog Soldier Society members clustered. In 1887, Congress passed the General Allotment Act under which Indian reservations were to be broken up into 160-acre parcels and allotted to the heads of families. His first wife was Ponca Woman who died in 1908, after which he married Long Face. Matches had no children by either woman and died on October 26, 1914.

The Sketchbook

![wounded_buffalo]](http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/files/2003/11/wounded_buffalo.jpg)

The Matches sketchbook (accession number 8016) was given to the Museum in 1891 by Mrs. E. W. Lehman, who also donated a number of Egyptian and Pompeiian objects. The book had been purchased by her between 1875 and 1877 while visiting St. Augustine, Florida, an area that had seen a steady rise in tourism throughout the late nineteenth century, as people of means needed to escape the increasingly last-paced environment of the industrial northeastern cities. The spread of three years suggests that the Lehmans made multiple trips to Florida and that Mrs. Lehman was unsure on which of those trips she had actually purchased the book.

The sketchbook itself is small (8.25 x 6.5 inches) and has marbleized front and back covers. There are drawings on thirty-one pages (recto [R], meaning the front or right hand page and verso [V], the back or left hand page), including drawings on both the front and back inside covers (pages 1R, 4R, and SR are empty). Because three of the total number of drawings are single compositions, covering two pages (6V and 7R, 8V and 9R, 10V and 11R], the number of drawings is actually twenty-eight. Each of the drawings except two [inside front cover and 6R], is accompanied by identifying text that was written by George Fox, the interpreter at Fort Marion.

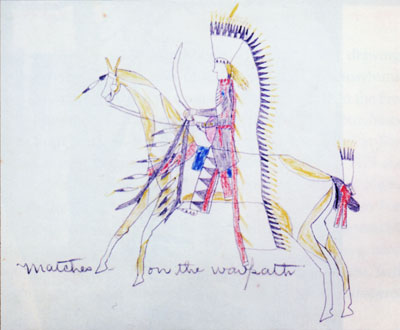

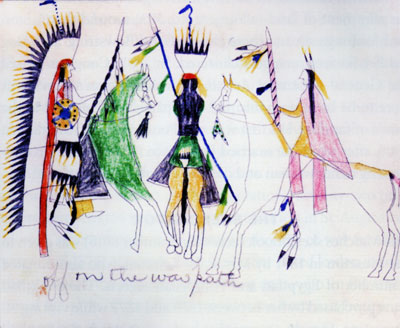

Although the sketchbook is identified as having been made by Matches, there are at least four different artists’ hands operative in the book. Two of the drawings are of Matches [figs. 2 and 3] and, presumably, were drawn by him (given the autobiographical nature of warrior painting). The majority of the drawings appear to be by this same hand, with some minor variations. Three other artists are represented by one drawing [7V], two drawings [2R, 16V], and three drawings 10V/11R, 13V, 15V]. To have several artists contribute work to a single book was not unusual. It followed a long, traditional practice of groups of men painting tipi covers or the interior linings of lodges. The ledger artists who drew in the Matches sketchbook may have been members of the same warrior society.

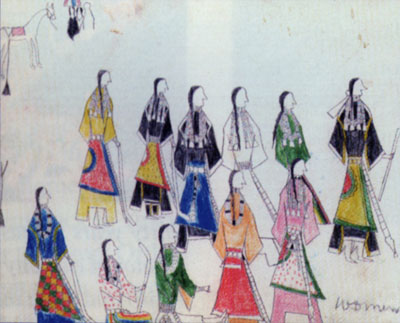

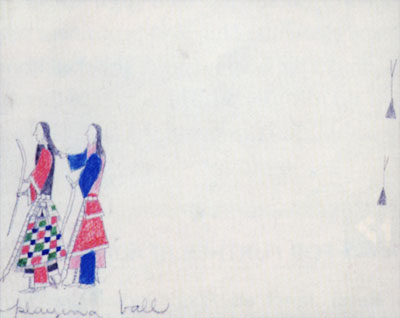

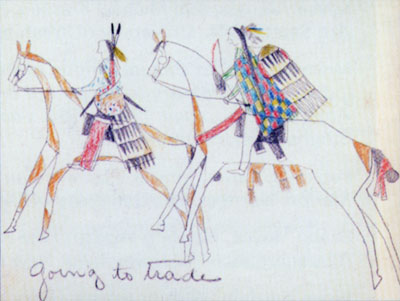

The subject matter of the drawings in the sketchbook falls into six categories. The traditional war scenes account for only six images [fig. 4]. There are eight hunting scenes [fig. 5], four camp scenes [figs. 6 and 7], one dance/ceremonial drawing [fig. 8], a single image of Fort Marion [fig. 9], and eight drawings of men on horseback, engaged in activities not related to war [fig 10]. The emphasis on a broad range of imagery follows a tradition already in place on the reservations. At Fort Marion the additional factor of patronage also needs to be considered. To what extent were the artists drawing in the Matches sketchbook responding to requests from visiting tourists for specific types of images: gentle, non-aggressive images of domestic life, the hunt, the dance? Or, to what extent were they being subversive? Three of the drawings [figs. 10, 5V, 7V], falling in the non-war related activities category, actually show horses with their tails tied up for war and implements of war drawn. The text, however, suggests a benign activity such as “going to trade” or “on the Grail”.

Generally, all the drawings appear passive rather than active, a quality that dominated drawing and painting in the reservation period. This static, “photographic” quality, complements these images of life as it had been lived: a snapshot of bygone days of warfare, the hunt, and trade. There is certainly an element of nostalgia present in the drawings. However, this same photographic quality may also be seen as an act of historic preservation, a conscious attempt on the part of Matches and his fellow artists to document and record those elements of their culture, which they felt were disappearing. Lending strength to this last argument is the amount of detail that is apparent in each one of the drawings.

The detail of the drawings in this sketchbook is directly related to the media employed: paper, pencil, crayon, and watercolor. The traditional implements of painting on hide were sharpened bone (for incising the design), flat bone (for the application of color), and mineral pigments. Even though the tools changed, the technique remained the same: the design was first drawn in outline and then flat application of color followed. The outline, in both traditional hide painting and ledger drawing, “holds” the color and remains a distinct element of the design. Using pencil, the ledger artist was able to achieve a level of detail never possible by using bone on hide. The drawing “Women Playing Ball” by Matches [figs. 6 and 7] exemplifies this beautifully. Distinctions between different types of earrings and necklaces; styles of German-silver belts, wide range of cloth available, including what are probably saltillo serapes; even the depiction of three “strike-a-light” pouches, suspended from belts; are all made possible by this new media. The applied colors (crayon and graphite used as a color) remain within the confines of the outline, and are applied evenly with no attempt at shading to try to create a sense of volume.

Composition and the placement of figures in space in these ledger drawings also follow the traditional format in most instances. Figures move from right to left [figs. 2, 3, 5, 8, 9], are drawn without a ground line, and generally without landscape elements. Depth is indicated not by foreshortening, but rather by stacking figures [figs. 5, 6, 7, 8]. Other elements of the traditional style of painting and drawing that appear include the placement of the horse, usually the largest element in the drawing first, the depiction of the human body, and the use of pictographic conventions to show movement and sound. In Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5, the horse is drawn first and the human figure added after, resulting in the line of the horse’s back being visible through the thigh of the rider. In the early robes, the human body was drawn with a full front view of the torso and the head in profile with no facial features depicted. This mode of depiction of the human figure continued on in ledger drawings (early commentators remarked on the “Egyptian” quality of the figures) but artists also began to draw figures from the side ]booth are shown simultaneously in figs. 6, 7, and 8]. Movement is indicated by the use of horse and buffalo tracks in the drawing “Wounded Buffalo” [fig. 5] and by the series of dotted lines that lead from the building to the group of uniformed prisoners in “Fort Marion [radians at Drill” [fig. 9]. Similarly, sound (speech), is indicated in the same drawing by the wavy line emanating form the officer’s mouth and sound (whistling), in the drawing “Medicine Dance” [fig. 8] by the lines issuing from the whistles held in the mouths of the two central figures facing each other in the composition.

While conforming to traditional techniques and conventions, Matches and the other artists of this sketchbook also attempted new compositions, ways of handling figures in space, and the addition of landscape features. Like other ledgers artists who produced drawings on the reservation before him, Matches generally used the single page as the framing device for a single image (figs.) 2, 3, 41. This sketchbook is unusual in that it has three drawings that break this pattern and use two facing pages for a single composition. Two of the drawings are by Matches [figs. 6 and 7, and 6V/7R], and one by another artist [110V/ Ilk]. Another untraditional feature includes front and back views of horses and men [figs. 4 and 9] and the use of landscape elements. The most prominent use of a landscape device occurs in the final image of the sketchbook, “Fort Marion Indians at Drill” [fig. 9]. The action of this drawing is set completely within the confines of the fort. There is no sense of scale: the drilling Indians are the important feature and so are the largest. The fort is simultaneously seen as a composite of all its important parts: the barracks, corner guard towers, cannon, bridge (all viewed from different perspectives). It was the same traditional manner of depicting a warrior. All the important elements needed to be present and recognizable: the horse, arms, legs, warbonnet, weapons.

Few of the artists produced drawings after leaving Fort Marion. When they returned to their reservations they found no market For their art: an art that flourished in the confines of a prison, was spurred on by the growth of a tourist industry, and departed from tradition (while simultaneously clinging to it) in hold ways that resulted in new, arresting images. The fact that the artist/warriors incarcerated at Fort Marion created these drawings — and many were made during the three year captivity — as souvenirs for sale to tourists in no way negates the fact that the drawings had deep meaning for their creators. ‘[he drawings powerfully embody the dual worlds that Native Americans would he required to live in from this time forward: the non-native world, where these images were seen as quaint views of the past, and, simultaneously, the native world, where the depiction of this imagery keeps the past alive.

William Wierzbowski is the assistant keeper of the American Section at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. His academic work was done in art history and anthropology at Wayne State University, with postgraduate work at the University of Pennsylvania. For nearly thirty years he has worked with Native America art in both a curatorial capacity (The Detroit institute of Arts and currently at Penn) and as an independent scholar. He has been involved in the exhibitions “Images of a Vanished Life: Plains Indian Drawings” (Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1985) and “Mad for Modernism” (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1999) as a co-curator and catalogue essayist. Within the broad context of Native American art, his research has focused on the tradition of Plains Indian drawing and painting, especially ledger drawing, and the history of collecting Indian material, primarily in Philadelphia. He has lectured on these topics both locally and at the Smithsonian, specifically on the Indian collection of George Catlin.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge and thank Barbara Landis and John L. Sipes, Jr., Cheyenne elder and tribal historian, for providing biographical information about Matches after he left Carlisle Indian School and returned to the reservation.

Berlo, Janet, ed. Plains Indian Drawing 1865 — 1935. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1996.Ewers, John C. Plains Indian Painting: A Description of an Aboriginal American Art. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1939.

Keyser, James, and Michael Kiassen. Plains Indian Rock Art, Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press, 2001.

Gallery, Garrick. “Picture Writing of the American Indians.” In Tenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, 1888— 1889. Washington, DC: Smithsonian lnsitution, 1893.

Petersen, Karen Daniels. Plains Indian Art from Fort Marion. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971.

Szabo, Joyce. Howling Wolf and the History of Ledger Art. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 1994.

Viola, Herman. Warrior Artists: Historic Cheyenne and Kiowa Indian Ledger Art. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 1998.