In the spring of 1992, University Museum excavators of the ancient Maya city of Copan made the remarkable discovery of an intact noble burial chamber. The burial, located in the city’s Acropolis, may prove to belong to one of Copan’s ákings. What made this discovery alál the more exciting was the recovery of 12 ceramic vessels with unusually well preserved, painted polychrome decoration. These vessels represent one of the largest groups of such objects ever recovered from a contextually documented Maya burial.

A crew began a probe into the stairway on the axis of Olive platform, carefully removing the huge blacks of the lower steps. In March of 1992, the crew’s excavator plucked a seemingly inconsequential, wedge-shaped stone out of the mixed fill beneath the stairs, and a black hole opened at his feet. Small though it was, the hole revealed the top edge of a cut stone wall. I peered inside with a flashlight and could just make out bone fragments and plaster debris. The small stone was in fact a wedge for the capstones that formed the roof of an ancient tomb. The next day we were able to slip a small camera into the opening, and from the blind-angle pictures taken, we could see clearly the remains of someone who had been laid inside over 1400 years ago.

The tomb itself is a rectangular masonry chamber, oriented north/south and sealed by eight large capstones. The chamber’s interior was a vibrant red color, from the paint on the stucco finish of the walls and floor to the red pigment covering the stone slabs on which lay the skeleton (Fig. 3). The individual, identified as a man, lay face up with his head to the north, his arms and legs resting on the unworked spondylus shells that surrounded his body. He was adorned with bracelets and anklets composed of shell and jade beads and wore an elaborate collar of large shell beards, some with incised anthropomorphic designs. His costume also included mosaic earflares of shell and jade, and probably a belt of some form with jade and obsidian decoration.

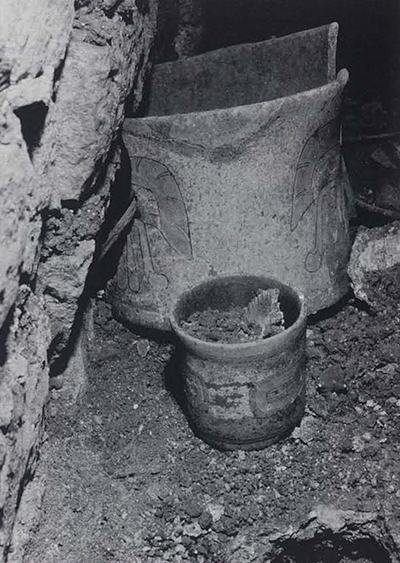

His funerary platform (perhaps made like the benches used in some elite residences of the time) was supported above the floor on six pedestal stones. On the floor around and underneath the platform hay pottery and other offerings (Figs. 4-8). Of the 28 ceramic vessels, a group of 12 display an unusually well preserved polychrome decoration (Figs. 7, 8). This finish, applied after the vessels were fired, is accomplished by covering the ceramic surface with a white undercoat of paint and then applying the varied colors to form designs of serpents, monsters, and hieroglyphs. These surfaces are delicate, arid relatively few well-preserved examples have been excavated in the Classic Maya area. Fortunately, a team of conservators is working to ensure the survival of all the objects from the tomb.

Alongside the ceramic vessels lay the remains of other polychrome-painted objects, unworked and worked shell pieces, stingray spines, and badly disintegrated organic materials. All the capstones spanning the chamber had cracked and part of one had fallen onto the funerary slab, tumbling some of the material into the pottery below. Otherwise, structural disturbance in the chamber was minimal, and the items placed on the floor were in their original positions.

Its stratifigraphic position, the pottery within the chamber, and a secure radiocarbon sample date the tomb to the mid-6th century. The location of the chamber and the wealth of the burial furnishings indicate that the deceased was a member of the nobility, and we believe it very likely that this nobleman was a Copan and The University Museum.

The interior of the tomb chamber before excavation, looking north. The poorly preserved remains of a single person were found lying on a funerary platform within the chamber. The person was a man from a noble family, probably a king of the Copan dynasty. Plaster debris from the red-painted chamber walls litters the stone platform and floor areas.

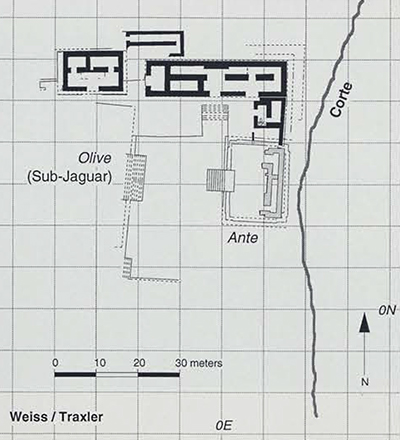

The ancient city of Copan, Honduras, is famous for its Hieroglyphic Stairway, its beautifully carved altars and stelae, and its monumental architecture. Copan is also famous for its unique archaeological section—the “Corte” (see Sharer et al. 1991). The extensive tunnel excavations from the Corte into the early East Court are one facet of the work being carried out by The University Museum’s Early Copan Acropolis Program (ECAP), under the direction of Robert Sharer. Since 1989, ECAP has been documenting the evolution of the Copan Acropolis as part of the Proyecto Arqueológico de la Acropolis de Copan, under the overall direction of William Fasts of Northern Illinois University. This project is an exemplary multifaceted, multinational effort, bringing together the Instituto Honclureno de Antropología e Historia and several universities, all committed to preserving the site of Copan for the future while investigating its cultural and historical legacy.

The tomb lies not only on the axis of the elaborate Ante platform. but also between two other important contemporary buildings situated to the north and south that form a perpendicular axis. As we continue to investigate this spatial context, we expect to uncover further indications that the chamber occupies a sacred locale.

Excavation of the burial chamber is nearly complete now, but months of work lie ahead for the analysis and continuing conservation of the various materials within the burial. From the objects we can learn the technology of their creation, as well as study the origins, significance. and esthetics of their decoration. The skeletal remains we can analyze for information on the individual person—his age, physical attributes, and health. But more importantly, the information we glean from these materials as a whole, in the social, historical, and stratigraphic context of the tomb, will help us understand so much more about the history of Copan and the culture of the Classic Maya.