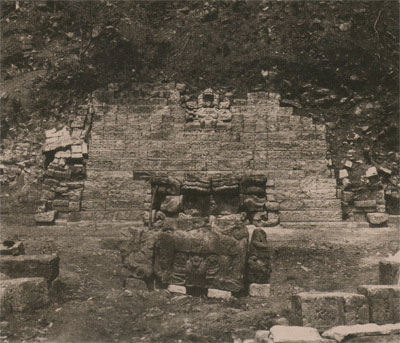

The ancient Maya city of Copan is a jewel of a ruin, a beautifully proportioned city situated in a verdant valley, comprised of soaring temples and enclosed courtyards, and adorned with intricately carved stelae. Within the site stands a unique monument of the ancient world, the Hieroglyphic Stairway of Temple 26, completed in 755 CE. Every block is carved with hieroglyphic inscriptions—2,200 glyphs in all, the longest known Maya text—that relate the history of Copan’s rulers.

Penn Museum Image: 228288

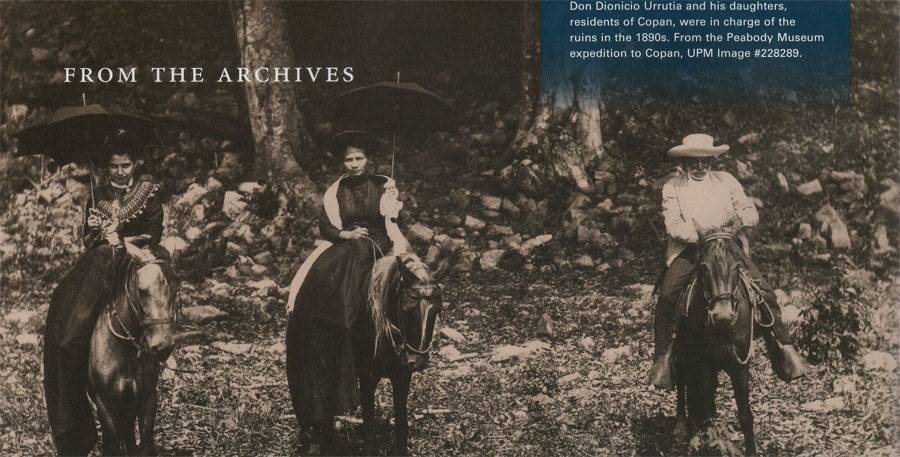

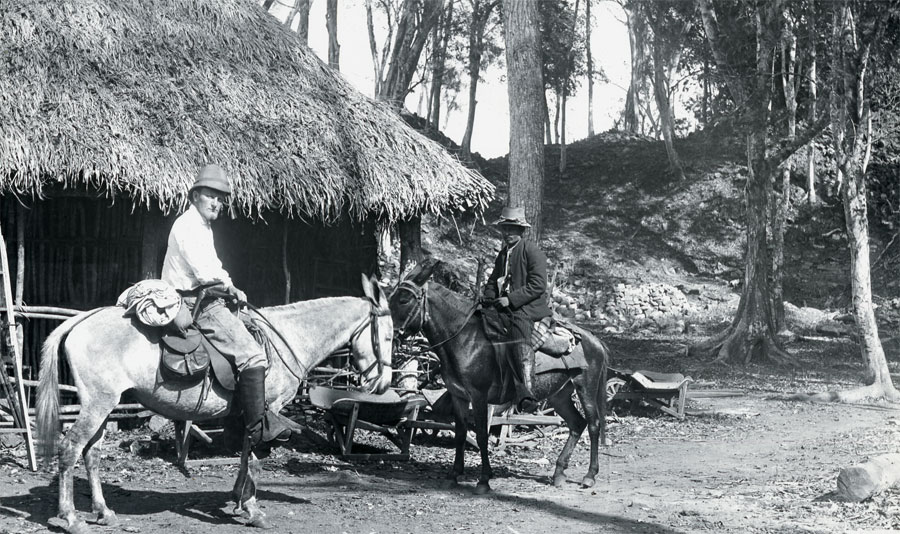

Copan was made famous in 1841 by John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood with the book Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatán, but it was not until 1885 that the Stairway was discovered by the pioneering British archaeologist Alfred P. Maudslay, who appropriately named it. In 1891, the Peabody Museum at Harvard University set up the first full-scale archaeological excavations at Copan, under the leadership of John G. Owens. Tragically, Owens died of fever the following year, leaving George Byron Gordon in charge. Gordon was a young Canadian graduate student who had been hired to survey and map the site. He was sent to direct the project again in 1894–1895 and in 1900.

Most of Gordon’s focus at Copan was on the Hieroglyphic Stairway. He found 15 steps in situ, but the majority of the blocks were either ruined or in a deteriorated condition and were dislodged among the debris of the pyramid. The hieroglyphic blocks were cleaned, photographed, numbered, and then lowered to the plaza. There they were placed on stone supports and photographed. Then molds were made of many of the pieces, a laborious task. The political situation in Honduras made work difficult for the Peabody Museum, and in 1901 the excavation permit ended. It was not until the 1930s that the Stairway was reconstructed as it appears today, by the Carnegie Institution of Washington.

Gordon punctually published the results of his excavations. However, he did not continue as a Maya specialist. In 1903 he accepted the post of Assistant Curator of General Ethnology at the Penn Museum, and by 1910 had become its director. Gordon greatly increased the profile of the Museum. Under his tenure, the institution grew, conducting research and fieldwork on several continents. Gordon, himself, built a reputation as a consummate connoisseur of fine Chinese, Egyptian, and other ancient and traditional art.

In 1923, Gordon was therefore surprised and affronted upon reading a footnote in the British Museum’s Guide to the Maudslay collection of Maya sculptures (casts and originals) from Central America that condemned the archaeological methods used on the Hieroglyphic Stairway:

Had the excavation been conducted from its inception with knowledge of the true conditions, a restoration of the inscription, by the exercise of the greatest care, should have been possible. Unluckily the component blocks were removed without the meticulous record which the circumstances demanded…The unhappy fate of this monumental record demonstrates the narrowness of the line which divides excavation from destruction and emphasizes the responsibilities of the excavator. One of the salient features of Maudslay’s extensive pioneer researches is constituted by the fact that they, in no single case, resulted in the destruction of evidence.

Gordon wrote angrily to Frederic Kenyon—the Director of the British Museum, with which the Penn Museum was collaborating at Ur—asking for an explanation. The reply came from T.A. Joyce, keeper of ethnography and author of the guide, who even in his letter appears to stammer in embarrassment at having insulted Gordon. He claims that he did not mean to offend, but rather was concerned about the possibility of future landslides…“I was anxious to warn future investigators against the possibility of landslides. That being so, I possibly neglected the ‘personal’ element, & I admit, in the light of your protest, the paragraph might have been better worded.” So he was, in fact, anxious to warn future archaeologists against committing the mistake that he was NOT accusing Gordon of having made. Joyce ends the letter beseechingly:

“Once more, Gordon, I’m sorry you’ve been hurt, but I can assure you that at heart I am ‘not guilty.’”

Gordon wrote a review of the British Museum Guide. In it, he picked apart Joyce’s publication, rallying in particular against the footnote. He goes so far as to point out that Maudslay himself may have caused damage to some of the archaeological sites he visited, but did not in the end publish the review. This draft remains in the Penn Museum Archives.

UPM Image #217932.