To protect his Danubian provinces, the Emperor Marcus Aurelius personally led campaigns against the Marcomanni from A.D. 166 to 172 and from 177 to 180. The costs of the war could not be sustained by the depleted treasury, so Marcus decided upon a public auction! The goods would come from the imperial palace. Actually on the Palatine Hill in Rome there were two palaces furnished with works of art and luxury items collected by earlier emperors. The Flavian Palace was the most modern and had been completed by Domitian in A.D. 92. Marcus Aurelius, like his adoptive father Antoninus Pius, disliked this structure and chose instead to reside in the old palace originally built by Tiberius early in the first century A.D. From both of these sources Marcus made his selection of imperial heirlooms and had them wheeled down to the Forum of Trajan in carts.

The auction lasted for two months with an auctioneer conducting the sales and a financial steward keeping careful records of the transactions. Years later, after the conclusion of the war, the emperor found a surplus of money still left from these sales so he offered to buy back anything which purchasers did not wish to keep. Some did take advantage of the offer.

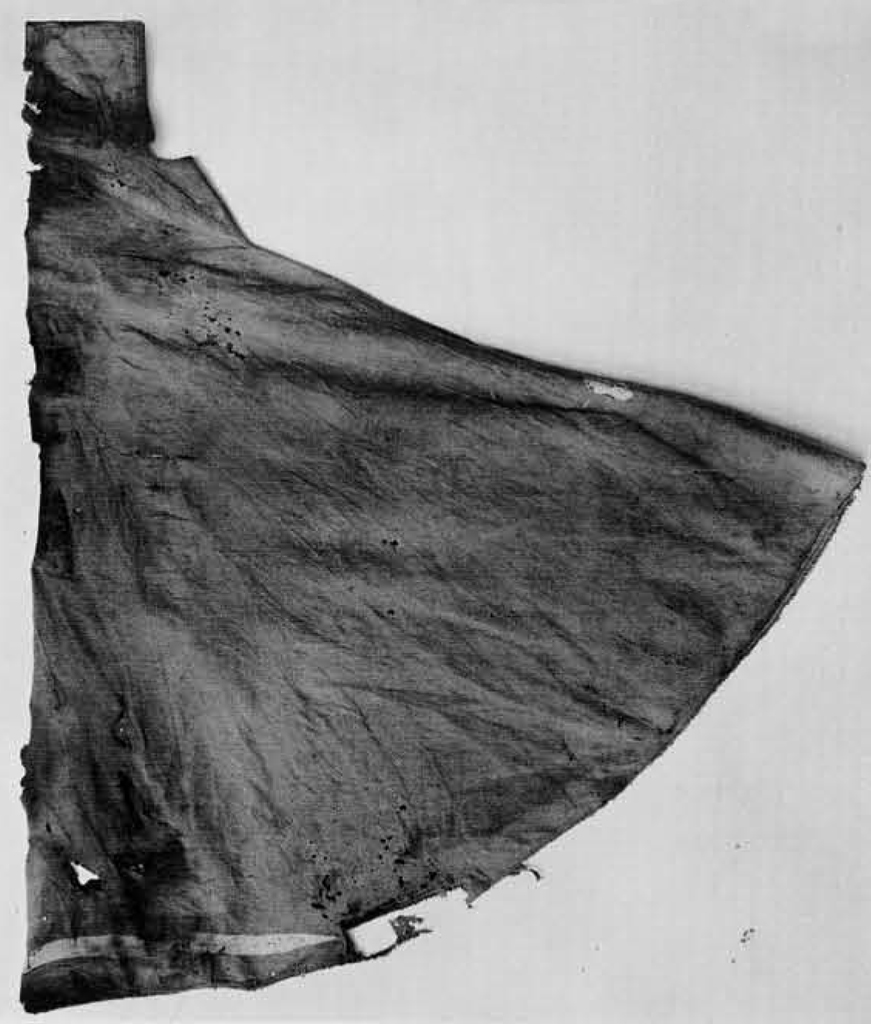

Ancient authors specifically mention the fact that Marcus included in his auction a fine selection of articles from his wife’s wardrobe. Within the palace, under the administration of the imperial treasury (fiscus), there existed a special bureau or treasury called the thesaurus which served as the repository for such things as imperial jewelry and precious plate. Among its duties also was that of maintaining and storing the state robes belonging not only to the empress but to the emperor as well. Whether the throne changed hands peacefully or not this clothing remained in the palace since it was used as an embellishment for imperial power. A special steward known as a procurator supervised all affairs of the thesaurus. In addition, however, there were separate wardrobes belonging to the emperor and empress which consisted of their own personal garments. It was evidently from this collection that Marcus chose the gold-embroidered silk robes (serica et aurata) which were sent off to Trajan’s Forum for sale.

By the third century A.D. the word serica, earlier used to indicate cloth looking like silk, partially made of silk or even completely made of silk, had come to require further definition. For clarification other words came into use such as holoserica for a garment entirely of pure silk and subserica for a fabric of silk mixed with other fibers. Faustina’s dresses may not have been woven of pure silk since Heliogabalus, forty-five years later, was supposed to have first used pure silk clothing. Yet Faustina’s garments demonstrate the ever-increasing amounts of money spent on imperial clothes and also the increasing availability of luxury fabrics.

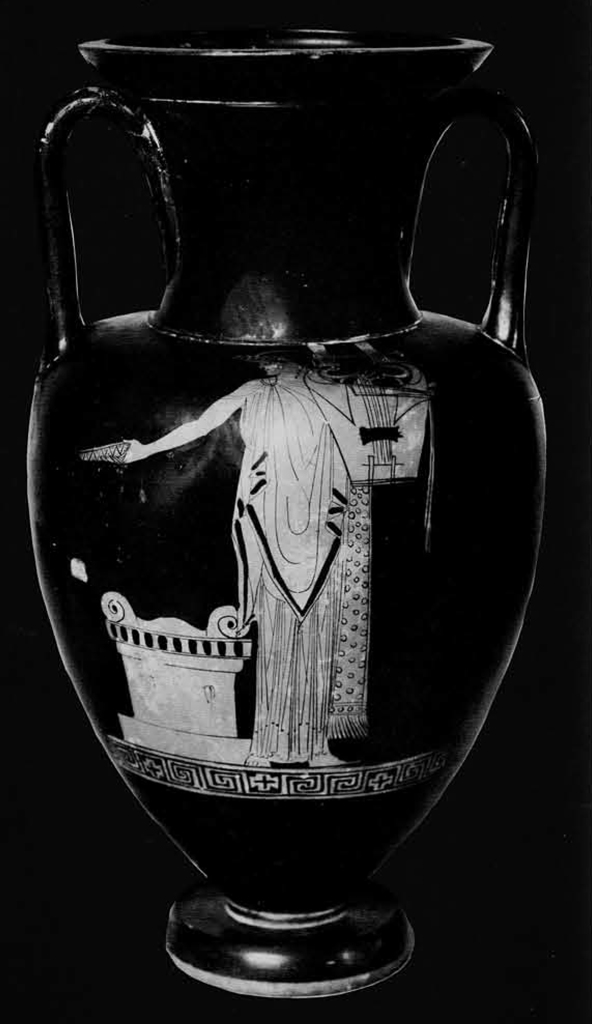

Almost two hundred years prior to this historic auction the imperial household neither thought of such an institution as the imperial thesaurus nor owned precious objects or garments which required such protection. The emperor Augustus lived in a fairly unpretentious house which had once belonged to Cicero’s old rival, the orator Hortensius. The emperor’s charming sister Octavia and his beautiful and intelligent wife Livia knew how to use a loom and Augustus insisted that his daughter and granddaughter also be taught how to weave. Around the house he always wore clothing made of their homespun woolen cloth. This was an old-fashioned way of life which he prized. In the household were servants not only to buy the wool for Livia but also to help her and her daughter spin it into threads. The weaving was done on a vertical loom (tela) with the warp (stamen) fastened to the revolving top beam and turned around the revolving lower beam. The thread (filum) used for the weft (subtemen) was handled from a bobbin (pannus) to weave the cloth upwards from the bottom of the loom. A comb (pecten), for pressing or beating the weft threads tight, would determine whether the cloth was wide-meshed (trama) or close-woven (densum).

The vertical loom with warp threads fastened to a revolving upper and lower beam was known among Near Eastern cultures at least as early as about 1300 B.C. when the form was represented in Egyptian art. The change from a horizontal to a vertical loom of this particular style permitted weavers to be seated as they wove the fabric from the bottom upward. Among the Greeks the vertical loom was also employed but without a lower beam. This meant that the length of the warp threads was limited to the height of the loom and the warp threads themselves were held taut by clay or stone weights tied to their lower ends. With this arrangement the weaver had to stand at the loom as she wove the fabric downward from the top. This concept continued into Roman times and the numerous Roman loom weights found in Egypt suggest that many weavers there had abandoned the earlier form with revolving upper and lower beams. The Ptolemaic rulers of Egypt made a government industry of flax raising and linen weaving. Weavers thus controlled by the state may have continued to use the more complicated and expensive vertical looms with upper and lower revolving beams. Individuals weaving only for themselves may have turned to the cheaper form using loom weights and only the upper beam. In A.D. 54 Ammonius sold to Tryphon, a fellow Egyptian, a loom with two uprights and two horizontal rollers. This was the better type with top and bottom revolving beams or rollers. The price was 20 silver drachmas.

In his words of advice to Roman architects, Vitruvius wrote about 25 B.C. that weaving rooms in houses should have a northern exposure so that the constant light would allow the best color work. This indicates that some homes would have a special room for weaving other evidence suggests that in the absence of such a room the looms would be set up in the atrium or reception hall. The four-foot-wide loom sold by Ammonius probably represents a standard size used in private homes. This practice of home weaving represents a situation still existing at Rome to some extent in the days of Augustus. Future generations would find this aspect of household work relegated entirely to slaves or even dropped completely. In Pompeii it may have been a slave who scratched on a wall the reminder that on the seventh day before the kalends of January (26 December) a start had been made on the stringing of warp threads on a loom. Another Pompeiian scratched a brief note of a linen and gold tunic.

All of the home-woven fabrics would be sent out to the fuller for washing and shearing. If they were to be colored, the services of a commercial dyer would be required. Returned to the house, the cloth was folded and sewn to the form of the desired garment. Ordinarily the loom permitted cloth to be woven to the size required for a single tunic or similar garment. Great lengths of yard goods were not produced for cutting into articles of clothing. As for the sewing, it evidently was not always what it should have been. In his mid teens, when Augustus performed the ritual of assuming his toga of manhood, his tunic came unsewn and fell to his feet. Many saw a good omen in this but in a more practical vein it shows that the tunic of a man was sewn together along the shoulders. Otherwise the undoing of the seams would not have allowed the garment to fall to the floor. Augustus never was a man of strong constitution and in winter he donned a woolen chest-protector (thorax laneus), an undershirt (subucula), four tunics, wraps for his thighs and shins, and a heavy woolen toga. There is absolutely no indication that his tunics were dyed or bore any other ornamentation than the two purple stripes, running over each shoulder to the hem in front and in back. Even his toga did not follow extreme fashions for it was cut so as to be neither too full nor too tight in its folds and draping. This was an important consideration since the toga by its form restricted the wearer to slow and rather majestic movements. One shaped for tight draping could be too restrictive while an overly-full toga might be a real hazard. Both Caligula and Nero experienced the embarrassment of tripping over their togas.

Though always made of wool, the Roman toga did change in form throughout the centuries. Under the early Empire, in addition to variations in its fullness, the toga could be woven with a heavy tightly beaten body (toga pexa) or a fairly loose open weave for lightness (toga levis) It was during the latter part of Augustus’ reign that togas began to appear with a very closely sheared smooth surface (toga rasa). This suggests that with the increase in demand for commercially-made fabrics and garments, the fullers tried to improve upon the old-fashioned appearance by closely shearing the woolen nap raised by the fulling process. Augustus himself did indeed keep a good, professionally-made outfit of tunic and toga in his bedroom to meet unexpected emergencies which would require his public appearance. This latter information suggests that the rest of his wardrobe was stored elsewhere. For important magisterial functions, however, Augustus kept no formal clothes in the palace but rather used those ceremonial togas stored in the temple of Jupiter; these were the purple-striped toga praetexta and the elaborately embroidered toga picta. Granted the privilege for induction ceremonies or military victory processions, high officials could also borrow these togas.

More common cloaks, dyed in solid colors, were surely in the wardrobe of Augustus. Among these would be the popular lacerna, an all-purpose mantle generally worn over the toga at public events in the theater or amphitheater. Woven of wool and quite thick in texture, it also served as a rain cape and could be purchased in white, scarlet, purple, or even black. Especially effective in bad weather were those lacernae made of leather. It would appear that the lacerna was not always hooded itself but often required the use of a separate hood (cucullus). Martial in one of his late-first century A.D. epigrams joked about a man whose green Libumian hood (cucullus) stained his white lacerna when the dye from the hood ran down over the cape. In other remarks Martial also referred to hoods as completely separate entities. The paenula, on the other hand, was a woolen cloak evidently made with its own hood attached. The popular use of dark-colored lacernae over the toga eventually aroused the ire of Augustus who decreed that this dark cloak should never be worn over the toga in or near the Forum. Another type of cloak was the woolen laena which seems to have been made of two thicknesses of cloth and laid claim to being the most ancient garment for Roman men. It frequently was rather short. The Greek pallium, also a cloak, was much like the laena since the terms were sometimes used interchangeably and eventually may have come to mean any cloak in general. In addition to such mantles as these, Augustus owned at least one broad-brimmed sunhat in the form of the Greek petasos and he tried to make himself look taller by wearing thick-soled shoes.

Museum Object Number(s): L-51-2

The empress Livia also appears to have avoided any charges of owning extravagant clothing. She must have had an assortment of under-tunics, outer-tunics or stolae, wrap-around cloaks or pallae, veils and certain unmentionables such as linen or woolen chest binders (fascia pectoralis, mamillare) for breast support. Her tunics, made of linen or wool, were probably dyed solid colors as was the general fashion and they may even have had some innocuous embroidery trimming. Although she may have worn house dresses of her own make, it is quite likely that a larger portion of her wardrobe came from commercial dealers. In this connection it is worth noting that Quintus Remmius Palaemon, while still a youthful slave, was taught how to weave. After he had achieved his freedom he set himself up in Rome as a teacher (grammaticus) during the reigns of Tiberius and Claudius. However, for extra income he owned several stores dealing in ready-made clothing (officinae promercalium vestium)!

Shortly after the death of Augustus in A.D. 14 his successor Tiberius attended a meeting of the Senate in which some members criticized the growing extravagance in private life. As the Empire waxed greater so had private wealth. Among other things, the Senate decided to forbid men to wear silk garments (serica) from the East. From Hellenistic times silk-like fabrics had been woven on the island of Cos, but now under Tiberius silk imports were coming into the eastern provinces from China. By water they were brought through Ceylon and India to the Red Sea ports of Egypt and so to Alexandria. Overland through northern India and the Parthian Empire they reached Syrian

From this it is quite clear that the empress’ regalia was numerous and quite valuable by A.D. 55. It also demonstrates that the state robes were kept separate from the clothes belonging to Agrippina personally. The imperial wives responsible for accumulating these garments can be accounted for. Claudius came to the throne in A.D. 41 with his third wife Valeria Messalina. Her successor was the famous Agrippina. Prior to Messalina there had been Caligula’s wife Caesonia. Tiberius had no consort. Thus the wives who added to the imperial wardrobes must have been Caesonia, Messalina and Agrippina herself. None were known for circumspection in taste or expenditures. But Tacitus refers also to mothers of the imperial family and there is only one such mother other than Agrippina. This is the dowager-empress Livia. Is it possible that as a widow, during the reign of her son Tiberius, she became a bit more extravagant in her clothing?

Nero himself eventually developed great interest in clothes. It was claimed that he never wore the same garment twice. Devoted to music and likening himself to Apollo, it was natural that he should adopt certain forms of Greek dress. When he returned to Rome from his triumphal concert tour of Greece he entered the capital wearing a purple tunic and a chlamys decorated with gold stars. It was Nero who forbade the public use of amethyst-colored dyes or Tyrian purple dyes. Once while performing on stage he noticed a female member of the audience dressed in purple. Fuming with rage he ordered his stewards to drag her out and strip her. Later authors castigated Nero for appearing in public in a dinner dress (synthesis) of linen with flower ornamentation, unbelted, without sandals and having a handkerchief (sudarium) around his neck. But this is the attire he wore in Greece according to the ancient Greek fashion prescribed for musicians. The garments must have come home with him and some surely went into the official wardrobe, adding another Greek touch to the assortment.

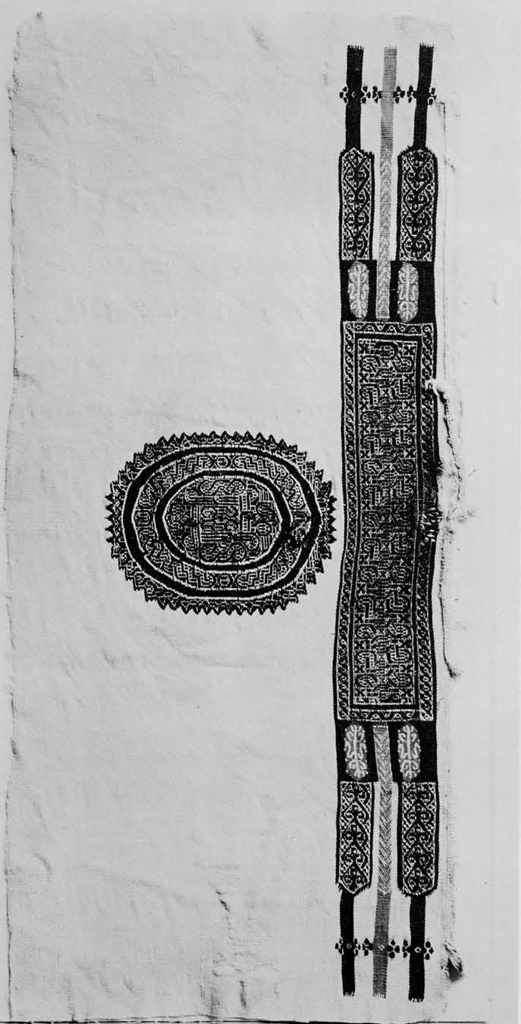

Museum Object Number(s): E16803

During Nero’s reign, if not before, it is possible that the official wardrobe came to include a toga praetexta and a toga pieta. The latter especially had become the official garment for imperial ceremonial appearances and as these occasions increased in number one of Augustus’ successors must have become annoyed at always having to borrow one from the temple of Jupiter. The obvious solution would be to create an extra set for the palace. In the time of Nero also the paenula underwent a further change through the use of a new woolen fabric called amphimallum, probably meaning that it had a long nap on both sides. It was now, too, that senators’ tunics were first woven with the same gausapina finish as the earlier paenula. Since Pliny the Elder makes this latter remark in connection only with the senators’ tunics, and since these tunics are the ones with broad purple stripes as opposed to the narrow purple stripes of the knights’ tunics, it is possible that he refers to the finish of the stripes themselves and not to the principal fabric of the tunics. The broad stripes would offer a larger and more obvious field for elaboration than would the narrow stripes. Thus it may be that here for the first time is the beginning of special attention to the appearance of the purple stripes, eventually leading to the beautiful pattern weaving and embroidery work later seen in tunic stripes, particularly in Coptic fabrics from Egypt and those examples shown in third century A.D. mosaics and later.

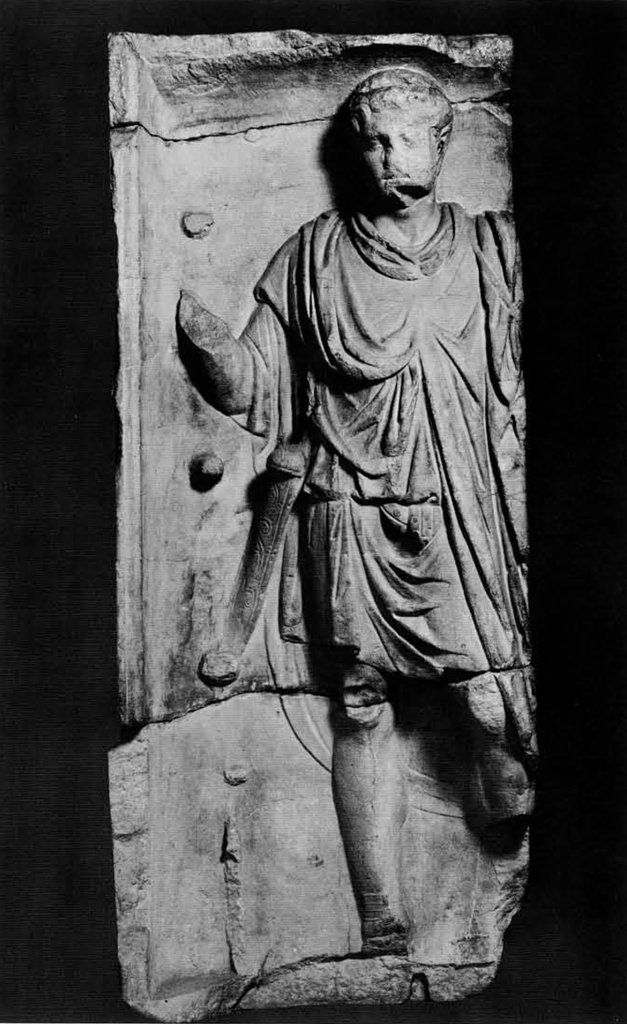

In the years following Nero’s death little worthwhile can have been placed in the imperial wardrobes of either emperor or empress. The time was too fleeting for Galba, Otho, and Vitellius. Vespasian had miserly inclinations while his son Titus reformed his spendthrift ways when he became emperor. Of Domitian it is said that on the occasion of his newly-established Capitoline Games he appeared in a purple toga draped round him in the Greek style. Since the games were modeled after those celebrated in Greece the reference may simply be to a purple himation draped in the Greek style. Otherwise, for all of his innovations, Domitian was not known to be extravagant or fanciful in his clothes. His wife Domitia also seems to have escaped censure in this area.

The elder senator Nerva, during his brief tenure as emperor, did sell some of his personal belongings to raise money. In the same sale he included items from the palace but, since they are only briefly mentioned without detail by the writer Cassius Dio, they probably were inconsequential. Martial, writing during his reign, indicates the general knowledge that silken robes did form a portion of the empresses’ wardrobe. Neither Trajan nor Hadrian spent much time in Rome and, along with their wives, seem to have used the imperial palaces very little if at all. But Hadrian certainly placed in the thesaurus the gold-embroidered cloaks (chlamys) sent him by Pharasmanes, king of Iberia, north of Armenia.

Museum Object Number(s): MS5465

Thus it would appear that the valuable imperial garments existing at the time of Marcus Aurelius had been contributed to the wardrobe largely during the first century A.D. Indeed these could have been preserved through careful folding and storing in wooden chests and cupboards (arcula, armarium, vestiarium). For warding off woodworms and noxious insects Pliny suggested sprinkling these storage containers with the lees of olive oil. For a pleasant aroma he urged packing nard or valerian among the articles of clothing. The clothes press (prela) was also employed and one example has been recovered in Herculaneum. Clothes brushes (muscarium bubulum) of oxtail hair could be used to dust off clothing before packing the pieces away. With this care perhaps there still existed some of the handkerchiefs which Nero’s elocution teacher held to the emperor’s mouth in public so that his throat might be protected for singing.

Under Commodus, the son and successor of Marcus Aurelius, the imperial wardrobe was certainly refurbished. This flamboyant emperor appeared in the amphitheater wearing a white silk tunic with long sleeves and gold threads woven all through the fabric. On occasion he dressed in a purple robe covered with gold spangles, a purple chlamys fastened across his shoulders. The sale held after his murder in A.D. 192 exposed for purchase more rarities belonging to Commodus. There were silk clothes interwoven with gold threads, long-sleeved Dalmatian tunics (chiridota), fringed military cloaks (cirratae militares), purple Greek cloaks (chlamys), purple camp cloaks, Illyrian-style hooded cloaks (aucullus), various other tunics, lacernae, and paenulae as well as gladiator’s equipment made of gold and gems.

The next emperor to make sartorial history was that strange Sun-priest from Syria, Heliogabalus who came to the throne in A.D. 218. His tastes were certainly non-Roman and may best be explained by remembering that his homeland was more a part of Near Eastern culture. Through Syria passed one of the silk routes from China. The Parthian Empire was not far away nor was Babylon, famous for its pattern weaving in colored threads of great variety. Heliogabalus owned at least one tunic made entirely of gold cloth. There was one, perhaps less distinguished, dyed all purple and another tunic covered with gems in the Persian style.

An ancient biographer states that Heliogabalus, according to reports, was the first Roman to wear clothing made completely of silk (holoserica) which strongly suggests that earlier garments described as silken were either imitations of silk-like fibers or else made of silk threads interwoven with baser fibers. This agrees with the modern understanding that the so-called silk of the island of Cos was not derived from domesticated true silkworms. It also conforms with the opinion that earlier Romans, finding imported Chinese fabric patterns not to their liking, had the threads unravelled and used for weaving more acceptable pieces, invariably including threads of less valuable fibers. Heliogabalus, too, was criticized for wearing long-sleeved tunics; after a dinner party he would often change into such a tunic, called a dalmaticus, and mix again with his guests. Considering his desire for ostentation and dislike for used clothing it is not surprising to read that he often ripped valuable garments to pieces!

Severus Alexander, who came to the throne in A.D. 222, wore no garment entirely made of pure silk (holoserica), owned only a few made in part of silk (subserica), and limited his wife’s use of silk and gold. Outside of Italy he usually wore a chlamys dyed with cochineal but in Italy he reverted to the respected toga. He preferred good linen clothing left undyed so that its smoothness would not be affected and he disliked the roughness of gold threads woven into linen cloth. The garments bought for his use were kept in the thesaurus for one year. Then, after personally inspecting them, he had the pieces given away. Certainly these were not valuable state robes but rather more ordinary items obtained annually.

The late second and third centuries A.D. saw many new fashion styles appearing in Rome and certainly these were included in the imperial wardrobe. Severus Alexander is said to have worn white trousers (bracae) instead of the scarlet ones previously worn. These loose-fitting trousers gathered at the ankles were introduced in Rome from Gaul during the second century A.D. The tunic also changed, particularly in the form of the vertical stripes. Whereas at first these had been sold purple in color and limited to two on a tunic, indicating certain social ranks by their width, by the reign of Aurelian (A.D. 270-275) the emperor is found giving to his soldiers tunics with stripes ranging from one up to five in number. The social distinction has been lost and the stripes are no longer solid purple. Already military tunics had come to display purple stripes but now the stripes are described as lace-like (paragauda) which certainly associates them with the lovely ornamentation found on Coptic textiles from Egypt. Earlier the emperor Gallienus had sent gifts to a military tribune, Claudius, which included a tunic with this same paragauda striping, the entire garment weighing three ounces. During Aurelian’s reign the consul Furius Placidus also gave similarly decorated linen tunics to charioteers in the Circus.

Museum Object Number(s): MS4916A

Tunics also had originally been quite simply made without true sleeves but with a fullness falling over the upper arms to give the appearance of sleeves. Yet the emperor Gallienus (A.D. 260268) was particularly singled out for wearing a purple and gold tunic provided with true sleeves. This indicates that tailors had already begun to cut real sleeves to be inset into the tunic.

Since the first century A.D., imperial clothing styles had changed considerably and the management of imperial affairs had grown from a melange of household slaves to a true government organization whose costs were largely borne by the imperial treasury. The thesaurus as it eventually developed was put in charge of a freed slave bearing the title procurator. The financial department of ratio purpurarum or the accounts of the imperial purple was quite possibly a creation of Severus Alexander. Also headed by a procurator, this department may have been responsible for costs in manufacturing state robes as well as the expenses of imperial purple dyes. Slaves in the imperial household, as in private homes, wove garments for the service personnel of the palace. With such facilities available it was natural that some provision be made for the production of imperial garments. Fulling and dyeing establishments would also be required and during the reign of Severus Alexander one Aurelius Probus served as praepositus baphii or chief of the imperial dye-works. It was this Probus who developed an especially brilliant purple dye at the urging of the emperor who wished to put it on the public market. Also by the time of Severus Alexander there were indeed fullers and tailors (vestitor) kept as slaves for serving the needs of the palace.

Low-ranking servants known as vestifices or vestiarii castrenses attended to the daily handling of imperial garments as they were needed. Lucius Agrius was a vestiarius tenuarius attended (in charge of thin vestments) for Antoninus Pius. Prosenes, who died in A.D. 2l7 while serving as chamberlain to Caracalla, was apparently a Greek freedman who started his career in the imperial household as ratio castrensis (keeper of palace accounts). Then he was appointed procurator vinorum (wine steward) and moved upward through the posts of procurator munerum (steward of services), procurator patrimonium (steward of the emperor’s private estates) and procurator thesaurum.

Even with this elaborate palace organization relative to the imperial regalia, many raw materials for producing clothing within the palace came from merchants in the city. These negotiatores stocked wool from all over the Mediterranean. Pertinax, before becoming emperor, managed a cloth-maker’s shop once belonging to his father in Liguria. Apulian wool was best used in making the paenula. White wool from the Po valley was very highly esteemed while the best black wool came from Spain. Other types were imported from Miletus, Greece, and Gaul. The best wools for darning were produced at Narbo in Gaul and in Egypt. Flax was imported from Gaul, Spain, and Egypt and even grown in Italy. Egypt provided the greatest variety and not all of the flax from other sources was deemed appropriate for cloth. Raw flax or flax already spun into linen thread could be obtained in Roman shops. Linen yard goods already woven came from northern Italy, Tarraco, and Egypt.

Raw dyes could be purchased but the general practice was to have the fabric dyed by commercial dyers. The best madder for dyeing wool was found in the neighborhood of Rome. As for purple dyes, so popular in Rome, there was a wide variety of shades available. Essentially all came from the murex and the purpurus but the quality of the color varied according to the particular mollusc and the location where it was found. Tyre, the best source, supplied a dark rose-colored dye (purpura) although something similar also came from Djerba south of Carthage. In other centers a dull scarlet (conchylium) was produced. By mixing the basic dyes the manufacturer could create a brilliant scarlet, a soft amethyst, or a very blackish purple. Additional effects could be secured by dyeing the cloth twice or by diluting the dye. The latter process was generally used for garments which were to be dyed in their entirety. Another reddish color came from the kermes insect found in Spain and Turkey among other places. The Italian persimmon, for one source, offered a yellow dye for woolens. From oak-galls came a black dye and from walnuts a brown dye for wool. Vegetable dyes offered a wide range of colors and could be secured from Transalpine Gaul but Pliny, in the first century A.D., complained that the colors faded with washing. This is a curious remark inasmuch as Pliny elsewhere indicates that Romans knew of alum as a mordant for setting dye permanently in cloth or fibers. Probably he was referring to dyed fabrics woven by the Gauls themselves and processed without the use of mordants.

Wool and flax provided the fibers for Roman clothing and dyeing was accomplished mostly in shades of red, purple, and blue. Black was essentially saved for mourning and browns were more likely used for workmen’s tunics. Yellow was available and green could be obtained by mixing other dyes.

Valuable ready-made garments could be purchased in the Vicus Tuscus, a street to ‘the southwest of the Palatine Hill. The shops in the Saepta Julia on the Campus Martius also had their valuable offerings such as ready-made Tyrian purple lacernae, possibly imported from Tyre. Most likely the extravagant silken robes interwoven with gold were imported from Egypt or Syria where the silk routes terminated and clever weavers knew how to make the best profit from exotic fabrics. In Egypt especially, gold was more than adequately available for weaving into silk or linen garments. Certainly in time Rome acquired weavers who could perform this fine work but the Near East must have remained the principal source. The many Greek-style vestments. of silk and gold or linen and gold or wool most probably came from Egypt where a strong Greek heritage still prevailed.

By the mid-fourth century A.D. the imperial government maintained innumerable weaving establishments manned by slaves and controlled by the Count of the Sacred Imperial Largesses. Working principally in linen, these weavers produced goods for issuance by the emperor to various personnel employed by the government. In the restrictive spirit of the times these weavers were compulsorily bound to the imperial guilds to which they belonged. The same control was asserted over collectors of purple dyefish. Silk goods were collected as a tax in kind from communities in the eastern part of the empire. In A.D. 369 and again in 382 it was forbidden for any private person to weave or use garments with gold or silk and gold borders. Finally in A.D. 424 not only was it forbidden to weave at home cloaks and tunics of pure silk dyed purple but all owners of such pieces were directed to surrender them to the treasury without reimbursement. Failure to comply with this law was a crime similar to high treason. Silk garments and purple dyes were for imperial use only. The opulence now evident in imperial apparel was indeed far removed from that simplicity which Augustus, the first Roman emperor, had hoped to establish.