Mapping

As a result of over 30 seasons of excavation Gordion has yielded one of the richest archaeological datasets in the ancient Near East. The lack of accurate spatial representations of the site, however, has consistently hindered the analysis and publication of the excavated material. A complete site-plan does not exist, and little of the ancient architecture can be precisely located in a site-wide coordinate system. The seriousness of this situation is difficult to overestimate. Most of the records for the excavation trenches and their assemblages were ultimately linked to architectural features, many of which no longer survive. Consequently, the key data cannot be located spatially with acceptable accuracy, either in absolute terms or relative to each other. The existence of specific problems associated with the mapping has long been known, and some of the architects responsible for the maps and plans attempted remedies over the years, but no appropriate solutions were ever found.

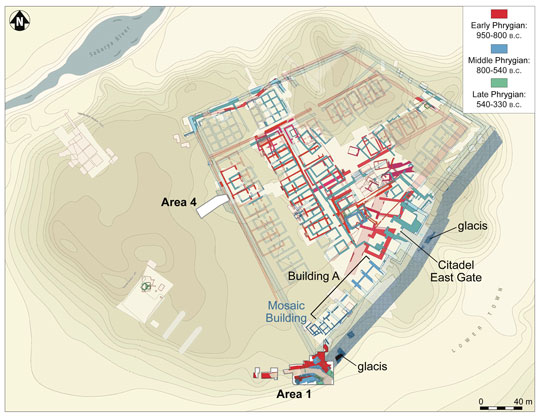

The true magnitude of the problem became apparent only in 2007, when two new initiatives demanded the accurate spatial referencing of Gordion’s data. Brian Rose had just become co-director of the project and suggested that a phase-plan of the Citadel Mound would improve comprehension and presentation of the excavation data. At the same time, Gareth Darbyshire and Gabriel Pizzorno commenced the Digital Gordion project, the goal of which is to improve the accessibility and analysis of the Gordion data through the digitisation of the archived records and the creation of an online research environment. It rapidly became clear that a new spatial referencing component would be required in order to fully integrate all the data.

That same year Pizzorno and Darbyshire begun a survey of the Gordion Archive that involved more than 700 plans and maps in varying degrees of detail, together with ancillary materials such as excavation notebooks, architects’ reports, and aerial and satellite imagery.

The maps and plans alone are insufficient for understanding the problem. Rather, a holistic approach is essential, taking into account many different types of information: the archaeological evidence itself (structures, deposits and artefacts) and the site’s topography; the operational context of the excavations (aims and methodology, personnel, organisation, logistics and scheduling); and technical details (the types, condition and capabilities of the equipment used at the time).

Over the last two years we formulated a strategy for dealing with the issues. Our highest priority has been the establishment of an absolute frame of reference to which any future reconstruction (and any present and future work at the site) can be anchored. The best way to accomplish this goal has been to use the Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) coordinate system. UTM provides a standard, world-wide system for specifying locations on the surface of the Earth, and is therefore impervious to the problems of a custom site grid.

Of crucial importance is a detailed understanding of the history of mapping at Gordion, and we therefore commenced exhaustive archival research. Through a detailed comparative study of the architects’ notes and the extant plans, some of the original errors were reconstructed and retraced. This work allowed us to identify the locations of fixed-points that had been used in the early site planning, but which had subsequently become buried and were considered lost. During the 2008 Gordion field-season, these models were tested on-site: a total station was used to locate a number of the missing fixed-points, and many other extant survey markers were also located and their relative positions precisely recorded. That same year all the mapping documentation extant at Gordion, which had never been accessioned into the Gordion Archive, was brought to Philadelphia.

As far as the creation of new plans is concerned, a good starting point is the careful mapping of features still visible on the ground. Steps in this direction were already taken in 2008 when a team from Brown University began a detailed survey of the Middle Phrygian architecture still extant on the Citadel Mound. This alone is insufficient, however, since most of the excavated levels no longer survive. Consequently, we formulated a system of ‘snapshots’ by using available imagery taken at different times over the last 50 years (in particular aerial photographs and more recent satellite images). These snapshots, once properly calibrated and geo-referenced, provide spatial cues for aligning the numerous plans of trenches and structures at different times during the history of the excavations. The central task of aligning involves the rectification of scanned digital images of the plans into a GIS containing as many known points as possible. As a result, the majority of plans can finally be accurately connected to physical features still extant on the ground, or to features visible in the legacy aerial imagery, or to other plans aligned in this process.

For the initial determination of absolute UTM coordinates for major features at the site, QuickBird satellite imagery has been acquired and rectified through a partnership with NASA. To complement the satellite imagery, a detailed site survey—using a differential Global Positioning System (dGPS) unit—was initiated during the 2008 field-season to determine the absolute global coordinates of the extant survey markers as well as the ancient stone buildings still standing. Modern dGPS measurements are usually accurate to within 2 cm from the true global coordinate of a point, and with repeated measurements of the same points from the total station, survey points can be anchored to within less than 1 cm of the true UTM coordinates.

In late 2008 we began rectifying and geo-referencing other imagery in the Gordion Archive against the QuickBird imagery, including aerial photographs from 1959 and a series of 15 balloon photographs of the site from 1989. In the spring of 2009, Philip Saperstein joined the project to assist with geo-referencing and management. We are currently testing automated algorithms to improve the accuracy of the matching. Once the close-range photographs are oriented in absolute coordinates, they should constitute a reliable basis for referencing a large number of the excavation plans.

The project was awarded a University Research Foundation grant for the 2009–10 academic year. Under our direction, a team of Penn students is working on digitising the maps and plans, and using the GIS to adjust these to features on the satellite imagery and aerial photos, thus projecting them into the UTM coordinate system. The accuracy of the process will be improved by comparison to known datum points surveyed at Gordion, and a vector plan of the site will be produced from the rectified plans. The current focus is on the plans from the Young excavation series (1950–1973), which constitute the bulk of the excavation trenches, structures, and fixed-points, to which the later plans of the Voigt series (1988–2006) were referenced. The plans and sketches in the field notebooks are also being examined and will subsequently be integrated into the GIS.

The Digital Gordion Mapping Project is directed by Gareth Darbyshire, Gabe Pizzorno and Phil Sapirstein, under the supervision of Gordion Project co-director Brian Rose. The project is currently funded by a grant from the University Research Foundation, and has also benefited from partnerships with:

- The Archaeological Mapping Lab directed by Dr. David Gilman Romano, at the Penn Museum

- The Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text and Image at the University of Pennsylvania

- The US Global Change Research Program at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center