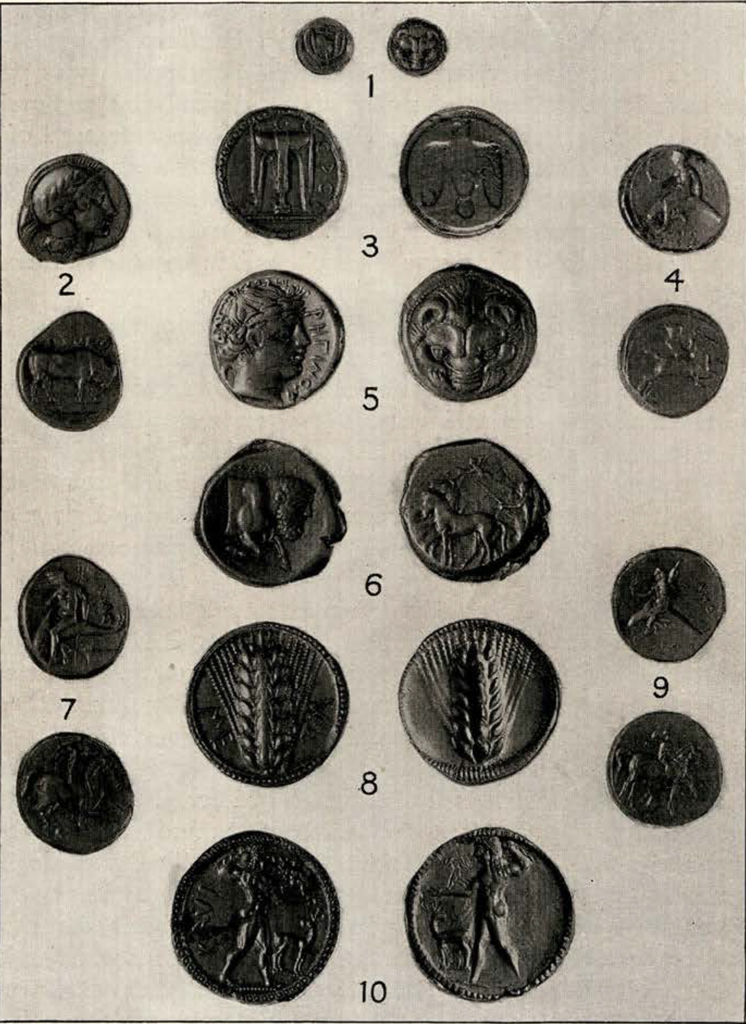

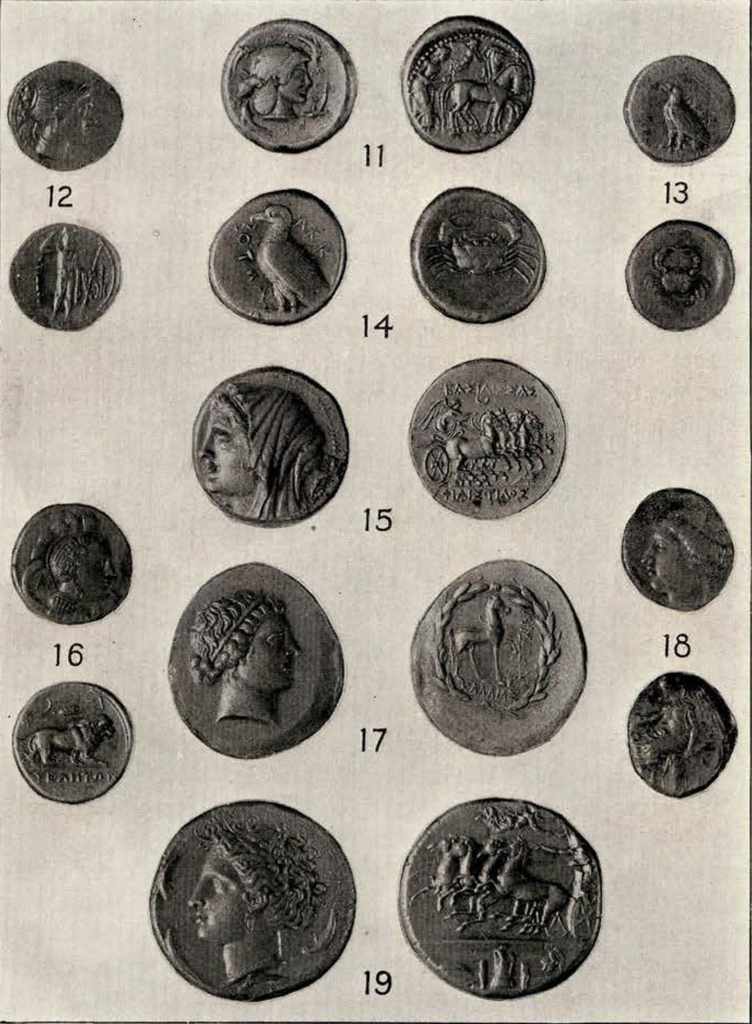

Coins are generally classed with the products of the Minor Arts, those arts which beautify the things man “handles and reads from and looks out of and kneels upon and laughs at and hunts with and in which he arrays himself, his family, and his house.”1 They are employed in the cheerful normal business of life and the decoration which guarantees their worth and so facilitates their owner’s business, may also beguile him a moment with its beauty. The group of coins shown in Figs. 37 and 38 is from the John Thompson Morris collection which was acquired six years ago through the generosity of Miss Lydia T. Morris. They were struck in the cities of Magna Graecia and Sicily in the spring time of Greek art and were of the mintages that were carried in the wallets of traders sailing their boats to the furthermost coves of the Mediterranean. Like the coins of Greece proper, they are beautified with devices so fresh, so various, so admirably adapted to their purpose, that they have been the despair of artists ever since. Two questions are of perennial interest, the one historical, the other aesthetic: how did such beautiful coins come to be made and what is it that makes them so beautiful?

The eye is caught at the start by the irregularities and imperfections of the minting; the coin No. 2 from Thourii, presents an outline by no means circular; in No. 10 from Caulonia, the delicate rope pattern of the margin is interrupted by a triangular break where the metal split. Another break may be seen in No. 6; here the die did not strike the metal true, and the craftsman was not concerned to trim away the overlapping metal. Such imperfections which would perhaps arouse the contempt of a modern craftsman go with great beauty of design, the reason being, apparently, that whereas the art of gem cutting had been practiced for centuries in Greek lands and had conquered all the difficulties of carving delicate designs in hard stones, the technique of striking coins from a die was only in its initial stages.

Image Numbers: 30558, 30559, 30560, 30561

The oldest of these coins Nos. 3, 8, and 10 were struck in about 500 B. c. only one hundred and fifty years after the interminable difficulties of cutting up metal, and disputing over its weight and quality were first overcome by the invention of coinage. Not till the seventh century B. c. did officials put their stamp on a piece of metal to show that it was of a given quantity and weight. It is no wonder then that the methods of fabrication were not yet perfected. The process employed in this early period was somewhat as follows. Blanks of metal of the desired size and weight were first cast in a mould. The die for the obverse or head of the coin was let into an anvil and the blank, probably heated, laid upon it without a collar. The reverse die was then held against the outer face and the hammer brought down. Dies wore out quickly and were often replaced which gave a people as imaginative and flexible as the Greeks a welcome opportunity to design new types.

It will be noticed that two of these earliest coins, Nos. 8 and 10, have the same design on obverse and reverse. Such coins give the impression of repoussé work but as a matter of fact two dies were used, the reverse in incuse. The two dies differed slightly; in No. 10, e. g., the running figure in Apollo’s left hand is omitted on the reverse. The advantage of this unusual fabric was that the coins could be stacked, but this advantage was soon lost sight of in the desire to enrich the coin further with a second device, and the technique was abandoned.

The colonies of Magna Graecia were founded for the most part by Achaeans as trading posts. The neighboring Italian cities being entirely friendly, no foreign foe retarded their growth. Each state was a political entity, and was bound to its neighbor by no other tiethan membership in an amphictyonic league and joint religious rites. The sovereign rights of these city states are attested by the coins the right to issue which is itself a mark of liberty. The situation then was typically Greek: a warm but tempered climate, brisk commerce by sea, full political liberty. Typically Greek also was the mutual discord which early set in to blight the rapid growth of these colonies. In 510 B. C. the powerful city of Sybaris was entirely wiped out by an army from Croton led by the famous wrestler Milo who carried an ox on his shoulders through the stadium at Olympia. For a time Croton enjoyed a brilliant leadership of the cities of Magna Graecia but she, together with Caulonia, was destroyed by Dionysios of Syracuse in 389. Tarentum was then the only city of importance left; from the period of her ascendancy dates a long series of coins, three of which are shown in Nos. 4, 7, and 9. But the Rcmans were pushing southward and even Pyrrhus and his elephants were of no avail to check their advance. Tarentum was sacked and plundered in 272. In Horace’s time it was nothing more than a pleasant winter resort and indeed Cicero could write in his day: Magna Graecia quidem deleta est.

Syracuse and the cities of Sicily were from the start under the ominous shadow of Carthage. Gelon of Gela, who in 485 established himself as tyrant of Syracuse, was finally able five years later to inflict a crushing defeat on the Carthaginians. Gelon’s successor and brother, Hieron, was also victorious, this time in a naval battle. And lastly the Syracusans inflicted the humiliating defeat on the Athenians, on the banks of the Assinaros, in commemorating which they yearly held the games called Assinaria.

Historical events such as these often furnished the types for coins. The motive was both to insure confidence in the coinage and to celebrate the glories of the city or ruler who issued the coins. Thurii for example was a colony of Athens and the beautiful helmeted head of Athena which appears on the obverse of the coin No. 2 must have assured the world that the finances of Thurii were handled by men of solid Attic worth. At the same time they were proud of their Athenian lineage and this head of Athena with its olive crowned helmet reflects, if but dimly, the glories of Phidias. On the reverse of this coin another bit of history is recorded; the bull is the old badge of Sybaris, which was so ruthlessly destroyed by Croton, and on the ancient site of which the new city of Thurii was founded.

At Rhegium, founded by Samos, the Samian type of lion’s scalp was adopted for a device (Nos. 1 and 5).

Tarentum celebrated on its coins the exploits of the mythical founder, Taras, son of Poseidon, who was credited with having founded a city on the site of Tarentum before the days of Greek colonization. He is represented (Nos. 4, 7, and 9) riding on a dolphin and carrying either a distaff twined with wool or his father’s trident.

Syracusan coins like No. 19 designed by the artist Evainetos are generally conceded the most beautiful coins ever struck. They also represent, though indirectly, an historical event. The crushing defeat of the Athenians which makes such sad reading in the pages of Thucydides was commemorated each year in the Assinaria, and the winning quadriga was pictured on the coins. A four horse chariot surmounted by a Victory was not a new device on Syracusan coins; Gelon had won victories at Delphi and Olympia and had put the victorious quadriga on his coins. But after 415 a Syracusan looking at these triumphant horses, would think only of the chariot races at the Assinaria. In the exergue is the armor given as a prize at these races.

Image Numbers: 30558, 30559, 30560, 30561

But a glance over the other coins will show how comparatively few of them commemorated historical events; an ear of barley, a crab, a tripod, a bullheaded man signified nothing either political or military. Rather in accordance with the heraldic instinct so ingrained in the Greeks, they symbolized the sovereign city by representing either its geographical situation or a distinguishing product. Metapontum was famous for her fertile plains and rich harvests. She dedicated at Delphi a xpvσoȗv ϴέpos, golden harvest—hence the ear of barley. The smaller of the coins from Rhegiurn, having on one face a lion’s scalp, had on the other, sprays of. olives. Croton, under the tutelage of Apollo, had Apollo’s tripod for its badge (No. 3). The high plateau of Agrigentum, the modern Girgenti (Nos. 13 and 14), was indicated by a proud eagle, the river that flowed past the city by a freshwater crab. The river Gela from which the town took its name was represented by a manheaded bull (No. 6). This kind of artistic shorthand, so useful for designating places was not merely pictographic but was entirely natural to Greek thought because a Greek conceived an indwelling deity in every spring and river. Farmers growing wheat along the shores of the river Gela, sailors pushing their boats past its maelstrom mouth in the spring, would have been in the habit of propitiating the river god with at least a pious prayer, and would at once have recognized the man-headed bull on the coin. Gods were closely connected with places; Apollo on the early coin from Caulonia (No. 10) is a local deity since he carries a little wind god to betoken the windy coast of Bruttium. No. 18 shows a beautiful coin from Terina on the obverse of which is a head of Niké and on the reverse a seated figure of the same goddess.

And lastly in pointing out the coins on which places or local deities are designated, we come again (No. 19) to the beautiful coin of Evainetos which bears on its obverse the lovely head of Arethusa, her hair bound with sprays of barley,-sacred to her mother Persephone. The dolphins that surround her denote the seas that gird the island round about and that reach by underground passages to the spring Arethusa itself.

Lenormant wrote of Evainetos: Evainetos est le plus grand de tons dans la branche qu’il a cultivée. Il est comme le Phidias de la gravure de monnaies. Regardez pendant quelque temps lane piece gravée par lui, et bientOt vous oublierez les dimensions exiguées de l’objet que vous tenez a la main: vous croirez avoir sous les yeux quelque fragment de Parthenon. The heads of Arethusa and the heads of Athena and of Nike in Figs. 19.2 and 18 do indeed suggest great works of sculpture, and this is in general so true of Greek coins that students of that art are wont to go to coins to fill the gaps in the history of Greek sculpture. Many Greek statues would be known only through late Roman replicas were it not for coins, which are both contemporary and original works of art. Whole schools of sculpture would in fact be lost were it not for the information about them derived from coins. The Apollo on the early Caulonian coin (No. 10) with his bulbous nose, large eye and exaggerated muscles, gives a good idea of a statue of the archaic period in 500 B. C. Similarly the ineffable grace of the seated Nike on the reverse of the Terina coin suggests the beauty of the Nike balustrade in Athens, but nevertheless the “dimensions exiguées” which Lenormant says we forget on the Arethusa coin are a determining factor in the decoration of coins. A writer on Aesthetics, to point the difference between sculpture and the minor arts, has called attention to the difference in mien and mood of people looking at sculpture and those handling coins and gems. Visitors to a sculpture gallery have an awestruck solemn air but when they come to handle a small coin “their attitude changes to one of unmixed delight.”2 If this point be well taken, as I believe it to be, and the minor arts reflect the sunny side of life, it will be seen that Lenormant’s comment that the coin seems to take on large proportions and that we seem to hold in our hand a bit of the Parthenon frieze, is not entirely a tribute to the coin. The decoration should not take on a bigger aspect but should be the lovely little thing it is and nothing more. It will be seen too how entirely appropriate to coins is an eagle, a crab, an ear of barley, a tripod, decorative not only because they adapt themselves so readily to the circular field, but because they are associated with the lighthearted activities of men, with man as fisher or hunter, not with man as prophet or poet or any kind of tragic figure. The Niobid of the Museo Terme would be entirely out of place on a coin.

And lastly these coins are beautiful because the information conveyed is not separated from the decoration. There is thorough “fusion of the intellectual and artistic content.”3 Sometimes, it is true, an inscription straggles along the margin of the coin, but in no such manner as do the neat and altogether explicit inscriptions of modern coins. As we have seen, the situation of the cities, the chief products, the Gods their citizens worshipped, are generally indicated without a word. The result is a simplicity, and a vividness unknown in modern art.

1 Rowland, The Significance of Art, p. 63.↪

2 Rowland, op. cit. p. 71.↪

3 Rhys Carpenter, Esthetic Basis of Greek Art, p. 24.↪