During the summer of 1912 the Museum acquired by purchase a collection of about two thousand specimens consisting of weapons, utensils, ornaments, clothing and images from a number of African tribes living in the Congo basin. This collection was, for the most part, obtained from the natives by the well-known German traveler, Frobenius. Though for a time it was exhibited in the central hall of the Museum no opportunity was found to give it adequate space owing to the overcrowded condition of the Museum. In order, however, to afford visitors an opportunity of seeing such an important collection, it was for a time installed temporarily on tables in a way which served at least to show what a variety of artistic activities and what a rich culture the native Congo peoples possess. Visitors had an opportunity of admiring the wonderful carved wooden boxes and cups, the elaborately wrought iron-work, the curious variety of knives, swords and spears, the delicately decorated calabashes and the cloths, woven from native fibre, and embroidered in a variety of patterns. In no other class of objects perhaps are the arts of savage peoples and the refinement of feeling which savages often display in the decoration even of articles of ordinary use, better illustrated than in the collections from the Congo.

Mr. E. Torday has lived for nine years among these Congo tribes, is familiar with their habits and has studied their ethnology. He was instrumental in procuring from the natives the wonderful Bushongo collection in the British Museum. Mr. Torday is now engaged at this Museum in cataloguing the Congo collections and the following article and photographs by him are of special interest in connection with these African exhibits.

—EDITOR.

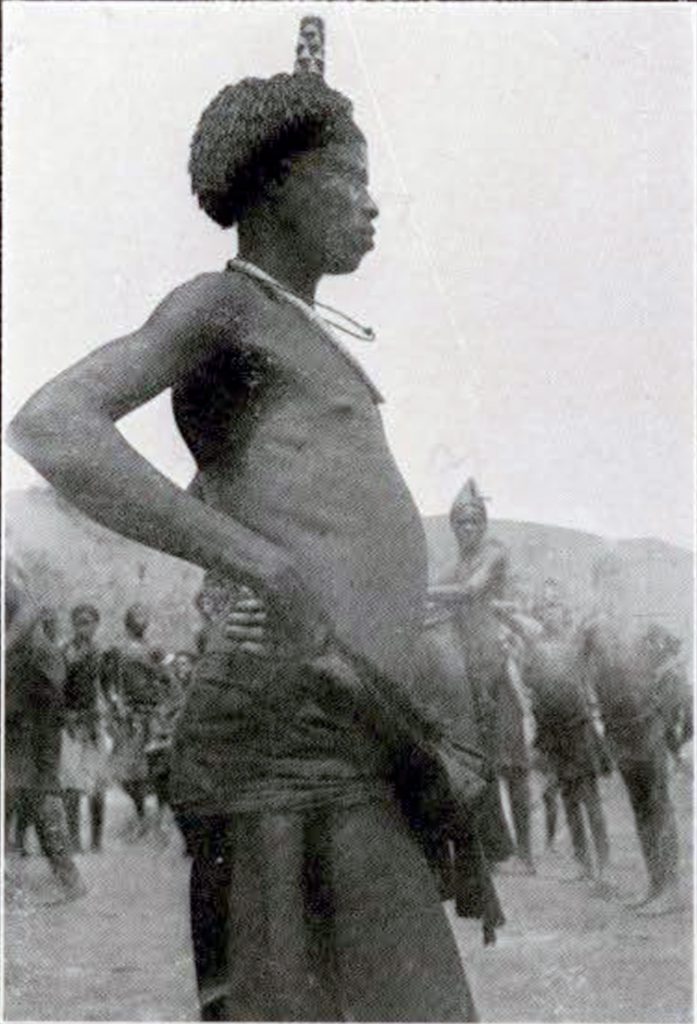

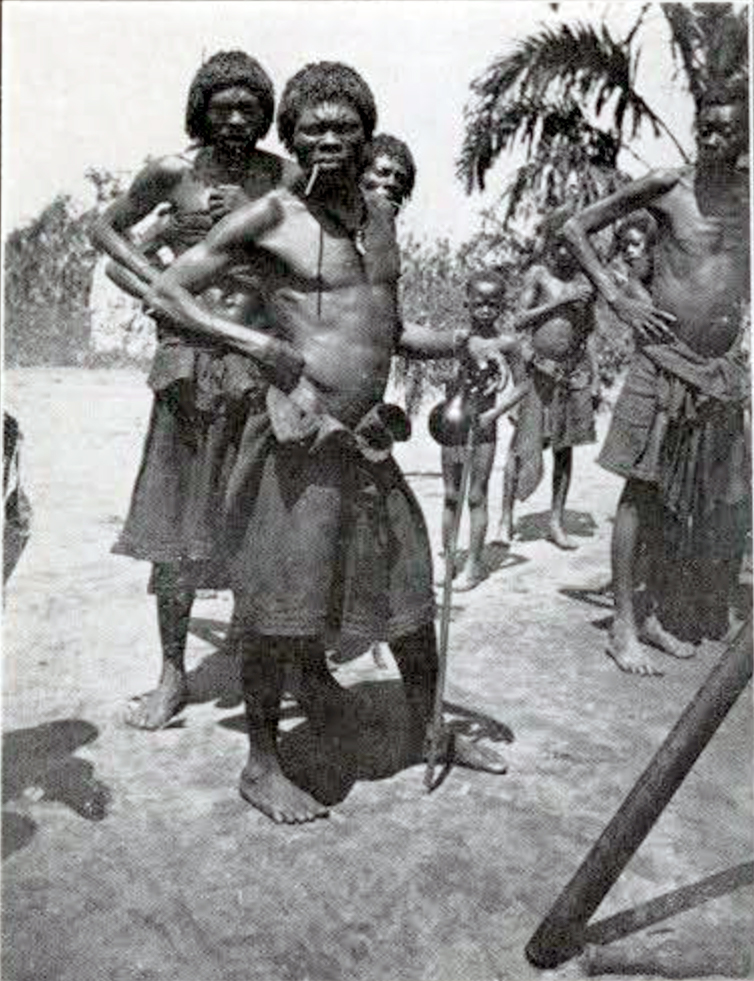

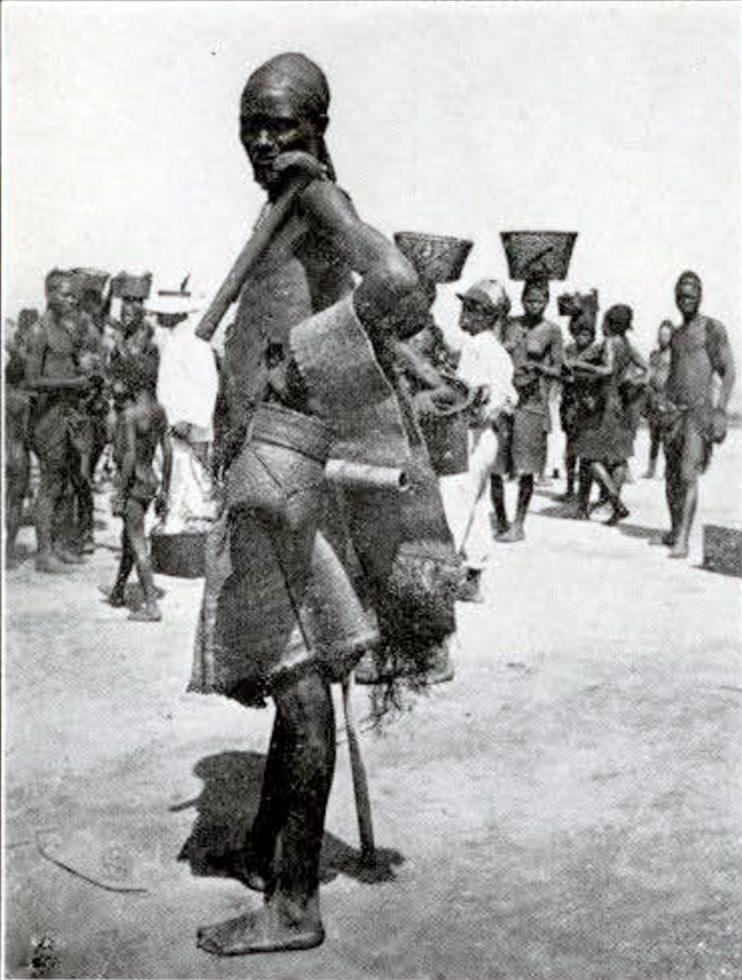

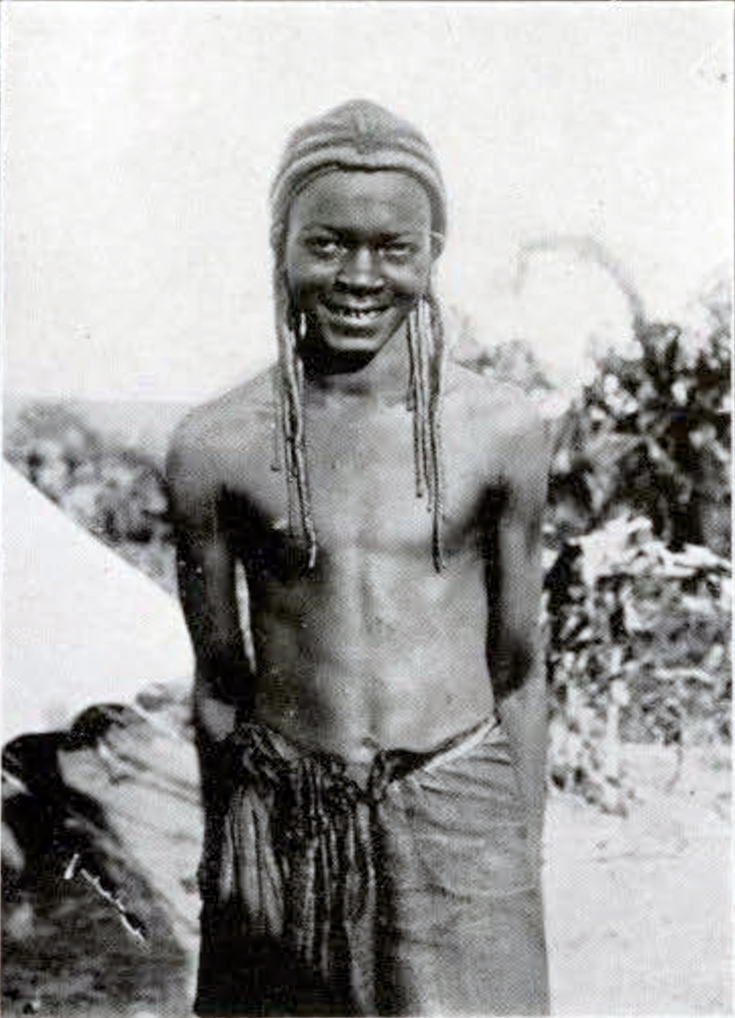

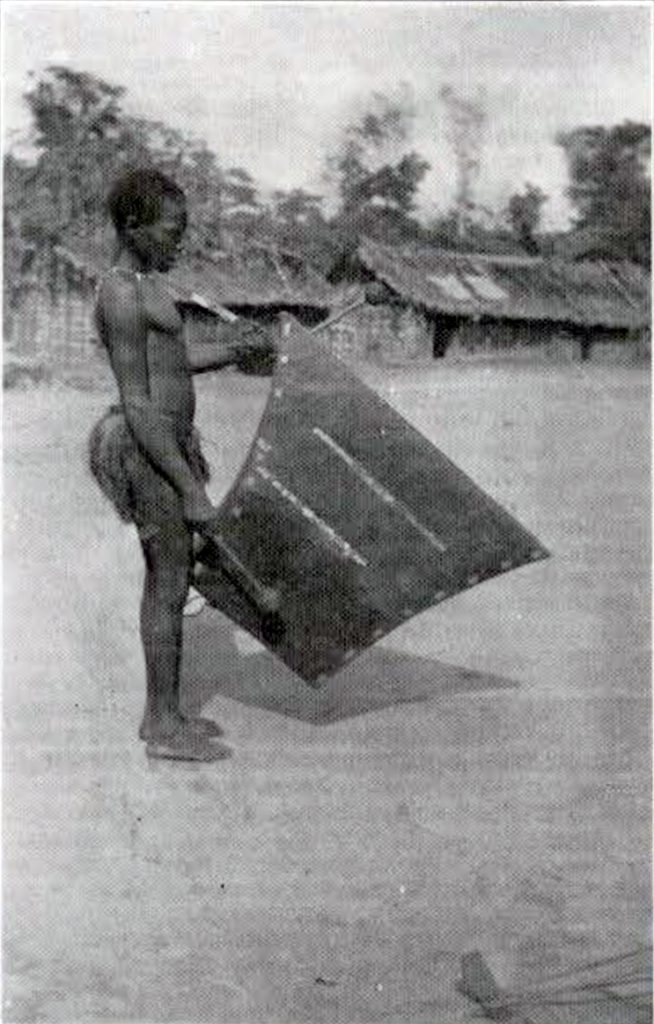

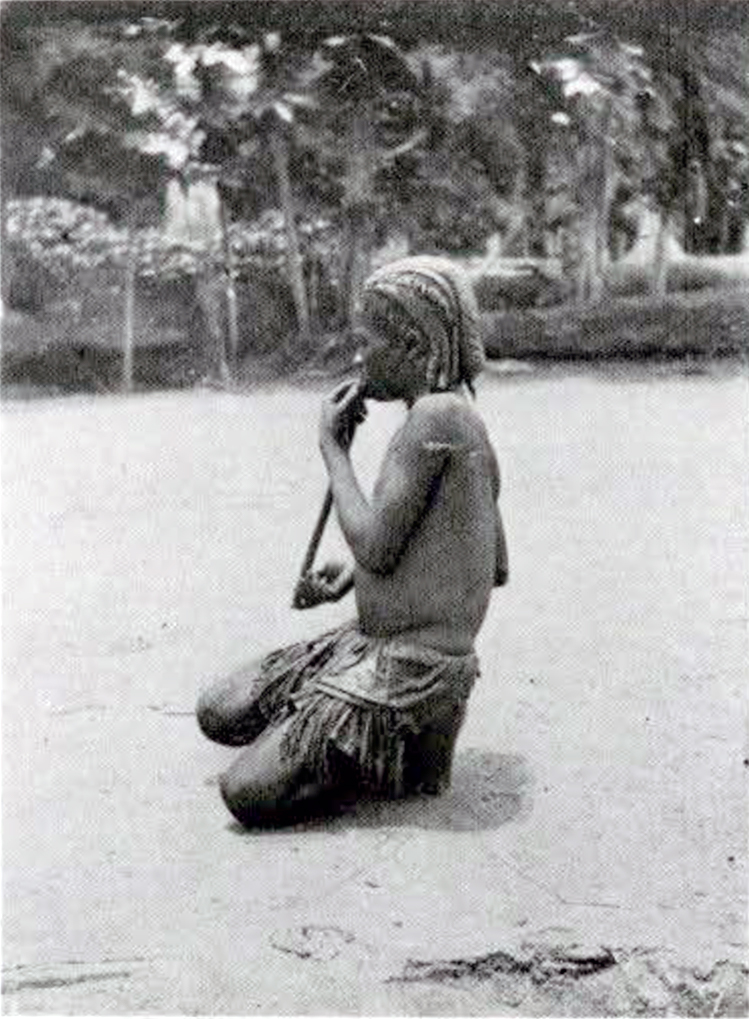

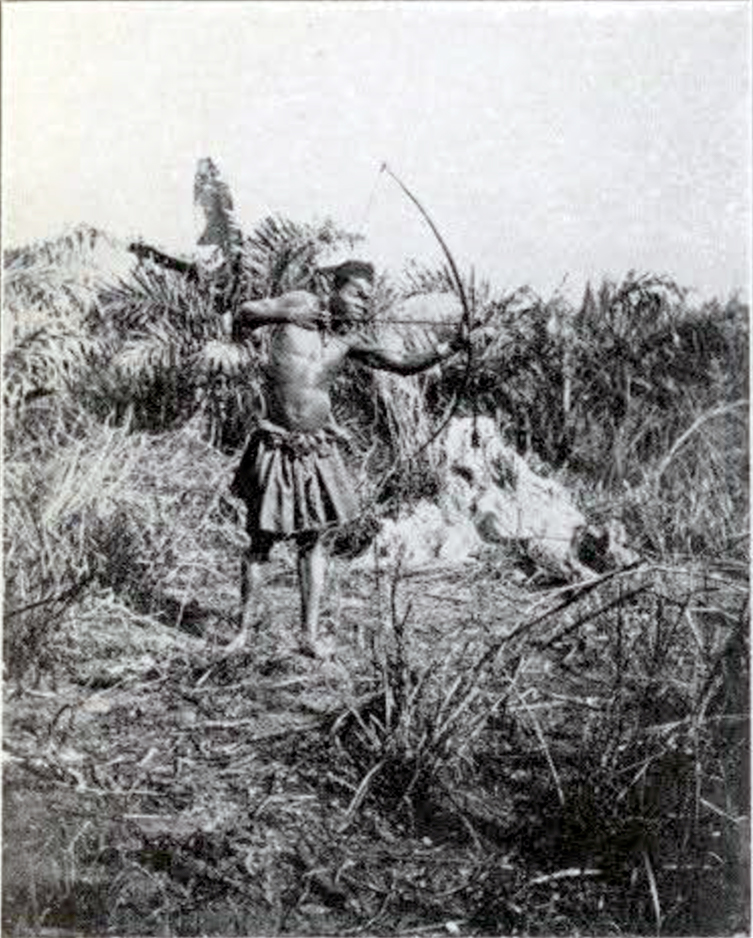

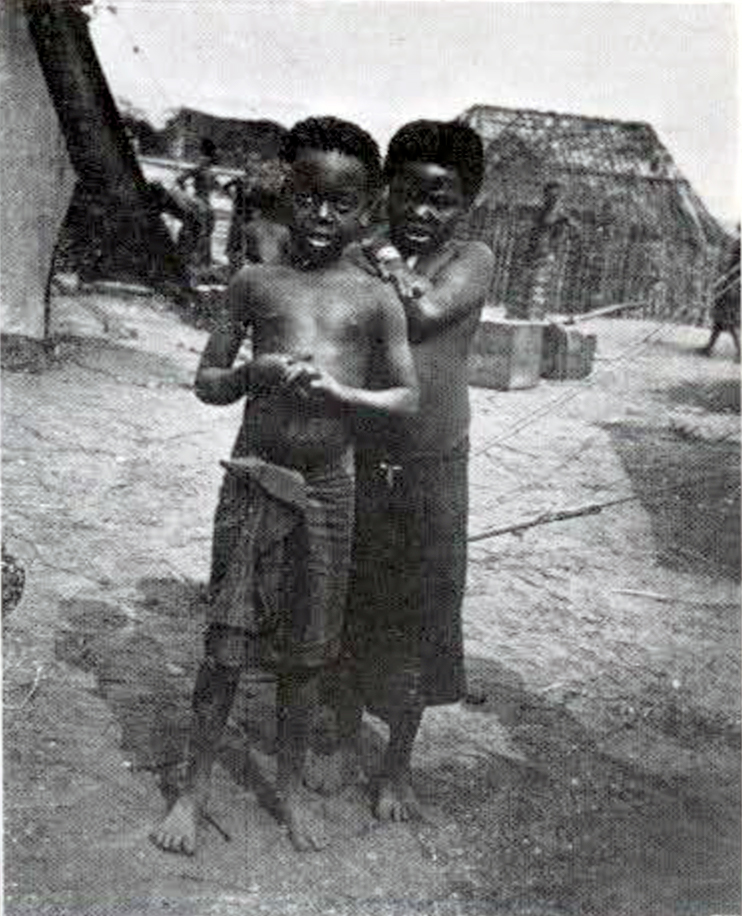

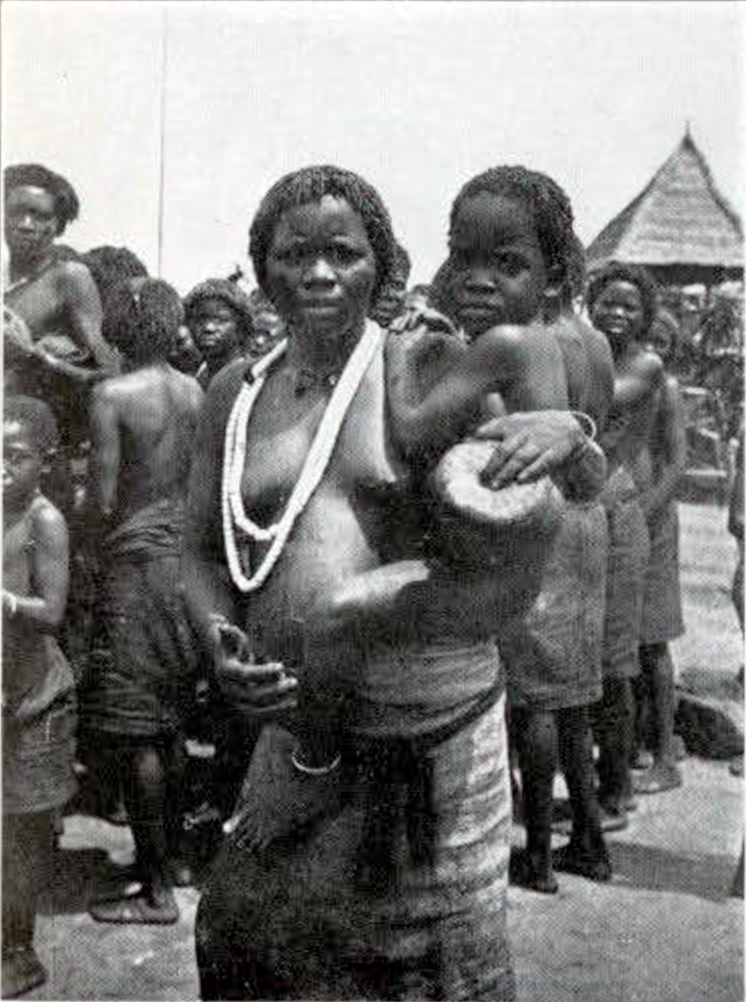

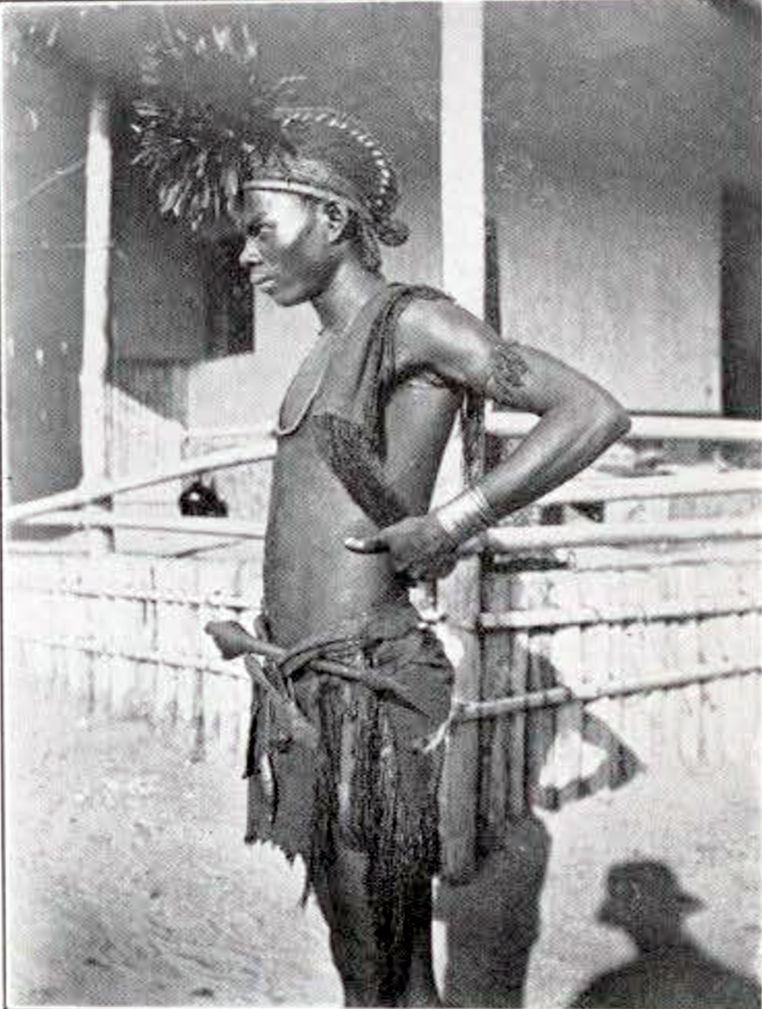

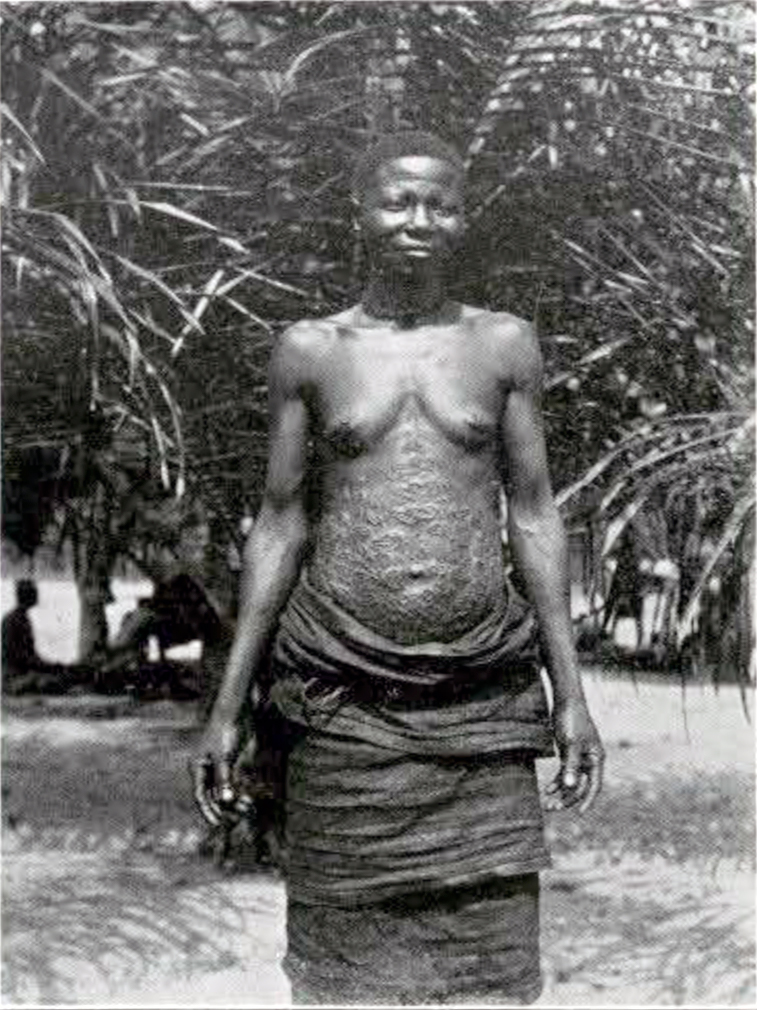

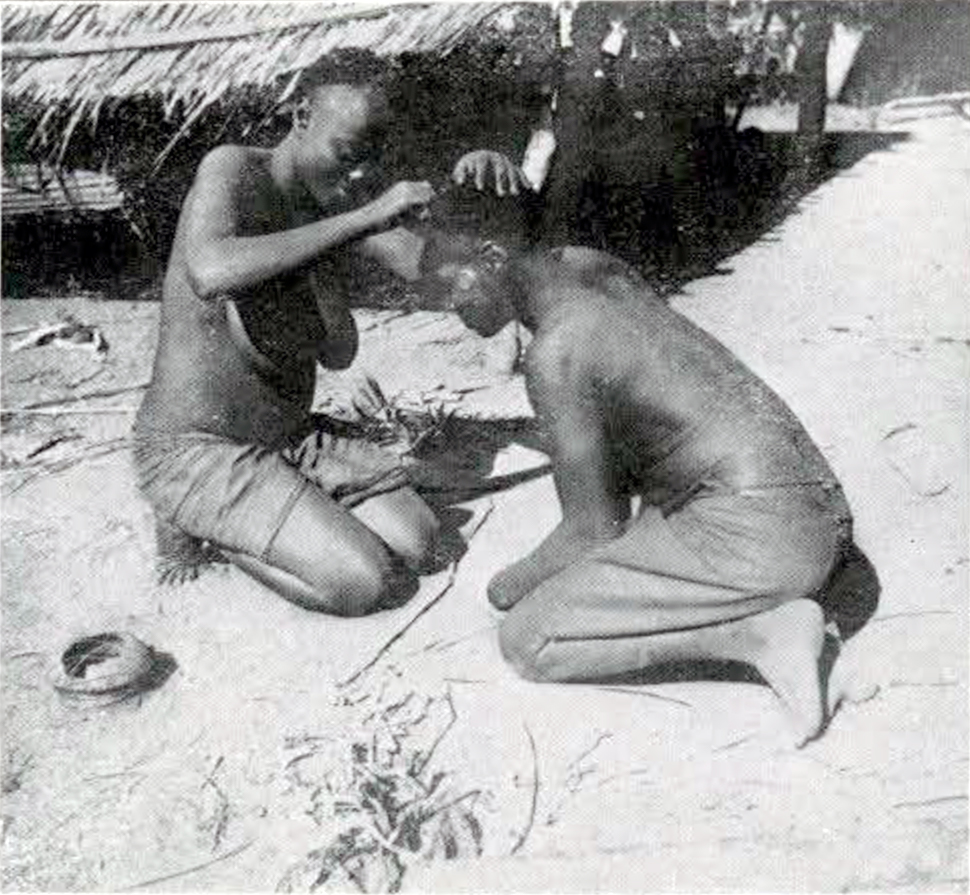

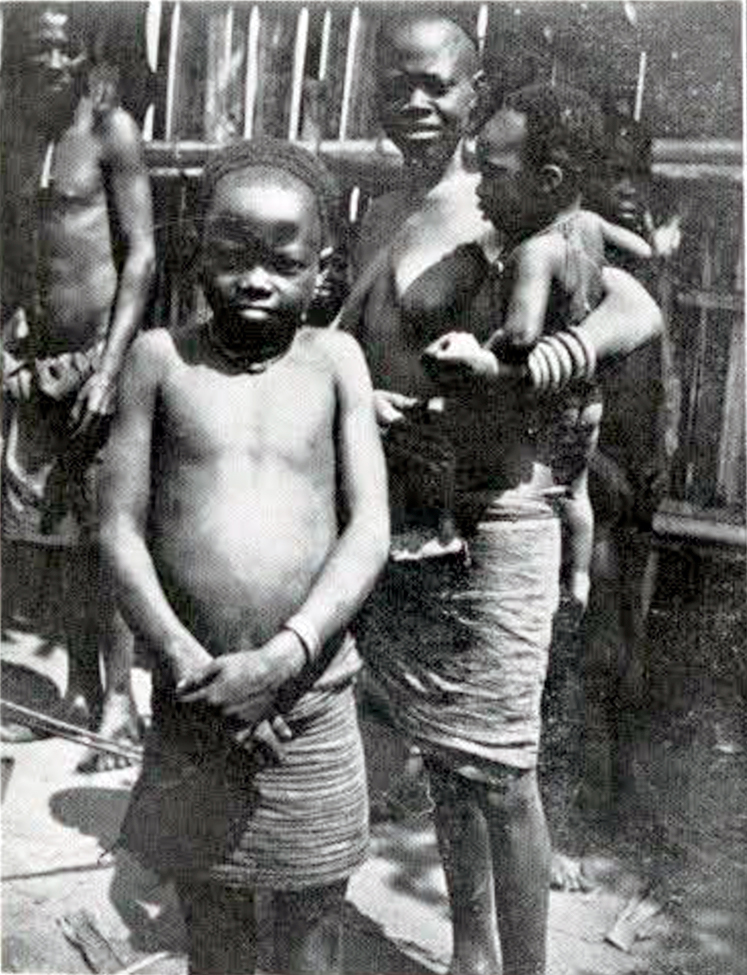

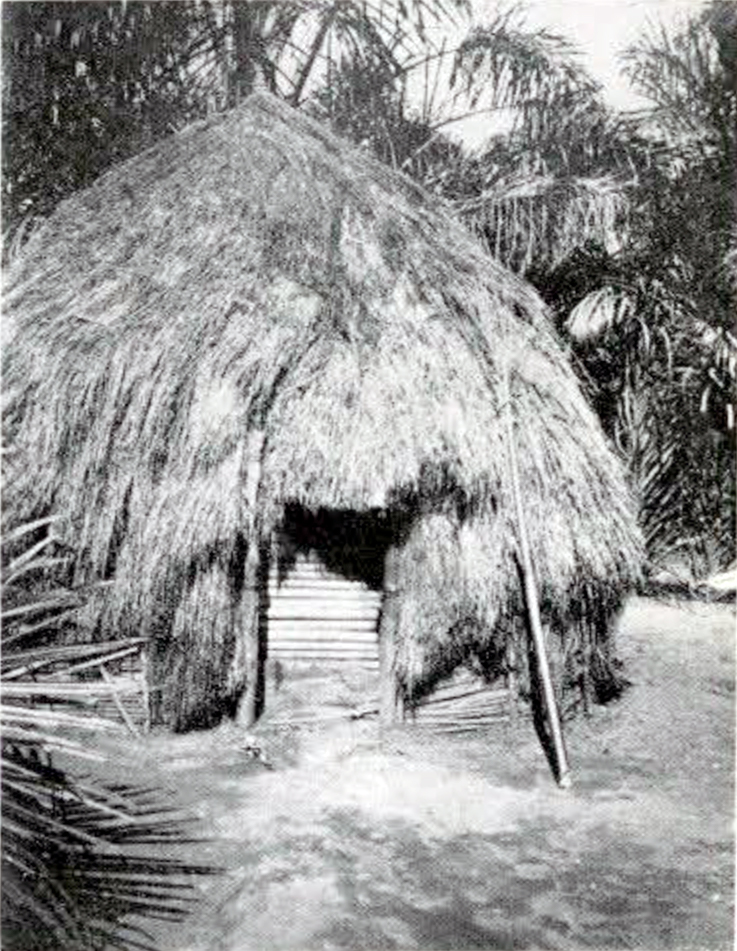

The various specimens of the newly acquired African collection belong mostly to tribes inhabiting the Congo basin. It is quite impossible to describe in detail so great a number of unfamiliar objects, consequently a sketch of the natives’ daily life will be attempted instead, leaving it to the reader to find out the role the different implements play in this. In the photographs which are shown herewith, a good idea may be derived of the appearance of the natives of the Congo, both young and old, their clothing and some of their occupations. In other photographs showing objects selected from the collection in the Museum may be seen some of the native arts at their best.

Very young children are quite unclad and when they begin to dress, their costume is frequently identical with that of their elders and is, in many cases, the same for both sexes. But while the dress is the same for boys and girls, it is curious to observe how, from an early age their toys and games, their occupations, their songs and dances are essentially different. For instance, boys and girls are in the habit of playing on a small flute, but whereas the boys play upon it with the mouth, the girls play it with their noses.

The characteristics of children vary according to the tribe. Thus the children of the Bashilele, who are agriculturists, are polite and shy, whereas the children of the Badjok, who are slave raiders and fighters, are quite as bold and aggressive as their elders. I can well remember once photographing a little Badjok girl a few minutes after she had tried to stab a boy who had inadvertently raised her anger.

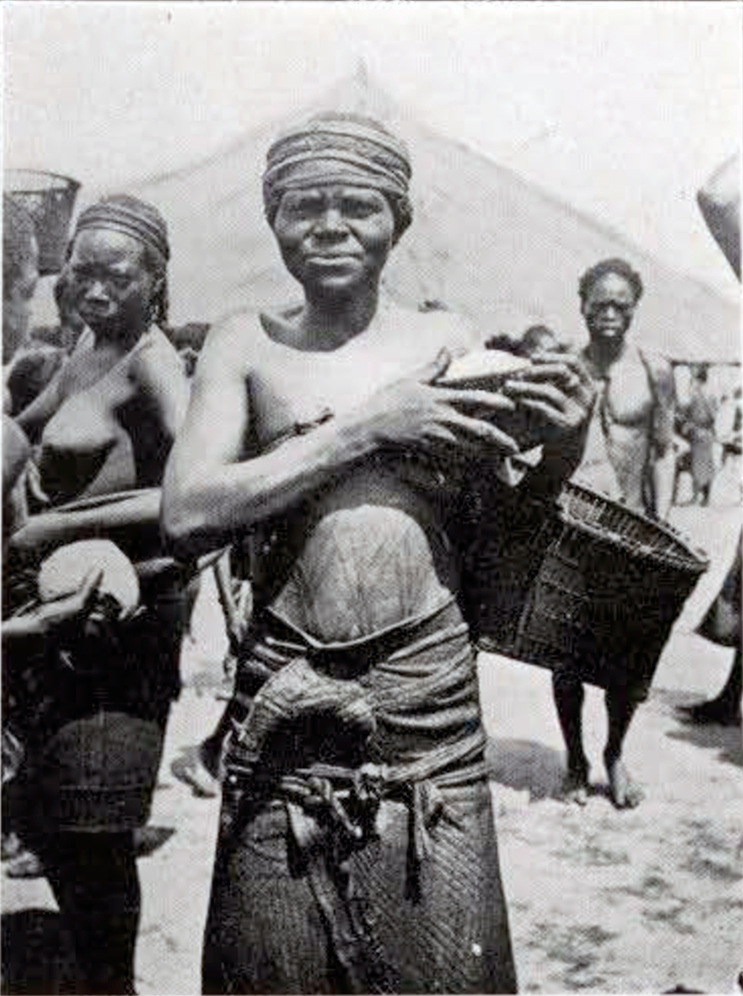

Dresses are cheap in the Congo, for, where they are worn, they are scanty and the result of the husband’s industry. The lack of dress is compensated by generous scarring of the skin; the illustrations, Figs. 13 and 14, will give an idea of the sufferings these poor victims of fashion undergo so as to outdo their best friend. But whereas in our country only women are supposed to submit with resignation to tortures for fashion’s sake, in the Congo man cannot claim exemption. He too has frequently his skin scarred and on the whole it can he said that the men in the Congo are vainer than women. War has been known to result among the Southern Bambala because a chief claimed to be handsomer than the lord of the nearest tribe.

The negroes have remarkably fine teeth and the efforts they make to destroy them are quite astonishing. Some, like the Southern Bambala, file them into points, whereas the Baluba and other tribes knock the upper incisors out. The Akela, however, are the worst offenders; as soon as they grow up, all their front teeth are removed from both jaws. Girls have this operation performed just before they get married, and it is a noteworthy fact that, notwithstanding that this operation is performed in a very crude way, is extremely painful, and is followed by the swelling of the face, there are no spinsters known in the Akela country. Having all their front teeth removed, these people cannot bite off pieces of their food; so when they eat, they hold a small knife with the big toe and cut their food upon it.

The negro’s hair lends itself in consequence of its woolly nature to all sorts of fantastic styles of hairdressing and the natives of the Congo make much of their opportunity. The Isambo lets the top grow as long as ever it can and then arranges it artistically round a wooden form so as to make it look like a cap; the two sides are carefully frizzled up in the shape of horns and the whole is dyed red with camwood powder. It takes many days to arrange such a coiffure and this is the raison d’etre of those curious neck rests so common all through Africa. The hair must be protected from any contact so as not to be disturbed. Before pronouncing judgment on the folly of these people we ought to keep in mind that French ladies of the time of Louis XV also wore hairdresses that required weeks to erect. White powder or red powder, the difference is really not so great as we are tempted to imagine. At any rate there are tribes in the Congo like the Babunda, where only men wear big crops of hair, whereas the ladies shave their heads. The resemblance between the hairdress and the shape of the roof of their huts found among the Bapende is worth noticing. When these people go to a dance they often wear tiny hats made of beads. The Congolese does not as a rule associate with a hat the idea of protection against heat or cold; as long as it is pretty, it fulfils all that is required from it; this will explain that in the Museum collection diadems of straw and bunches of feathers will be found labeled “head-gear.”

The reputed laziness of the African will be found on close investigation to be nothing else than conservatism. The negro enjoys the work he is accustomed to do, and likes to do what his father did and do it in the same way. He is the same as conservative men all over the world.

The working of iron is one of his favorite occupations and we find chiefs and kings working as smiths. In the village the bellows re worked by boys who do it frequently for the fun of it, and the smith’s shed is never empty.

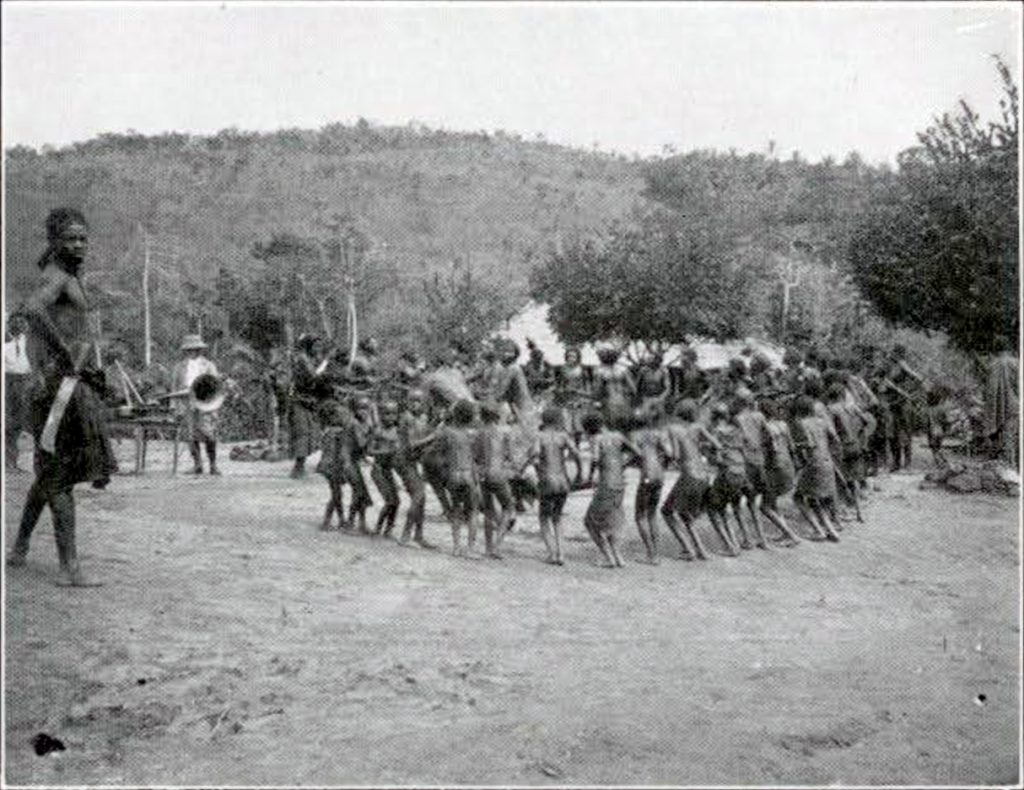

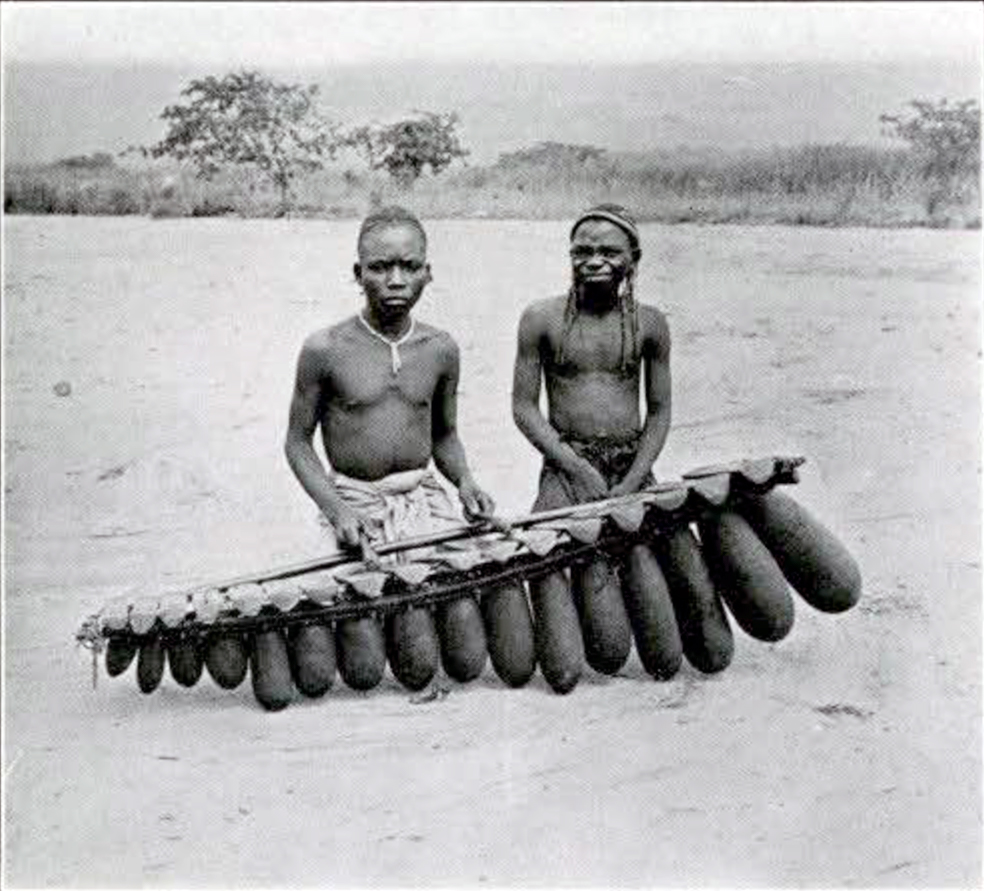

His work done, the native enjoys a quiet smoke, and the different pipes used among the various tribes form a valuable part of the Museum collection. However, the greatest joy of the Congolese, as of all negroes, is music and dancing, and a look at the photograph shown in Fig. 15 cannot leave anybody in doubt as to whether they enjoy it or not. A dance may begin in the afternoon or in the evening, but you may be quite sure it will not stop before morning. Carriers, taking a moment’s rest, having walked for twelve hours with fifty pounds on their backs will jump up at the sound of the tom-tom, drum or marimba and join in the general merriment.

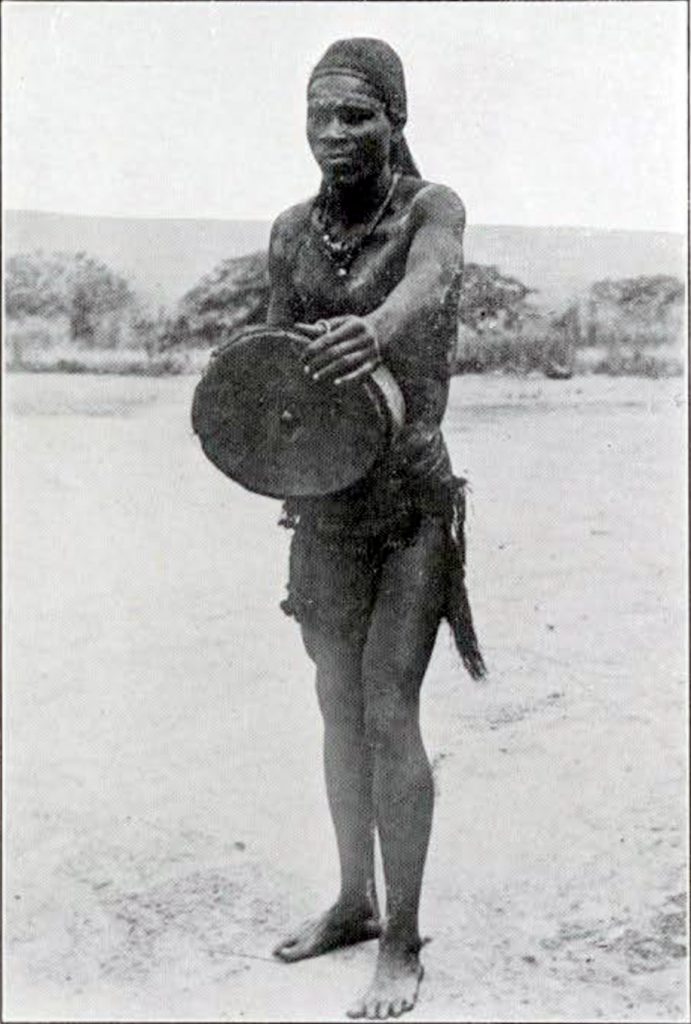

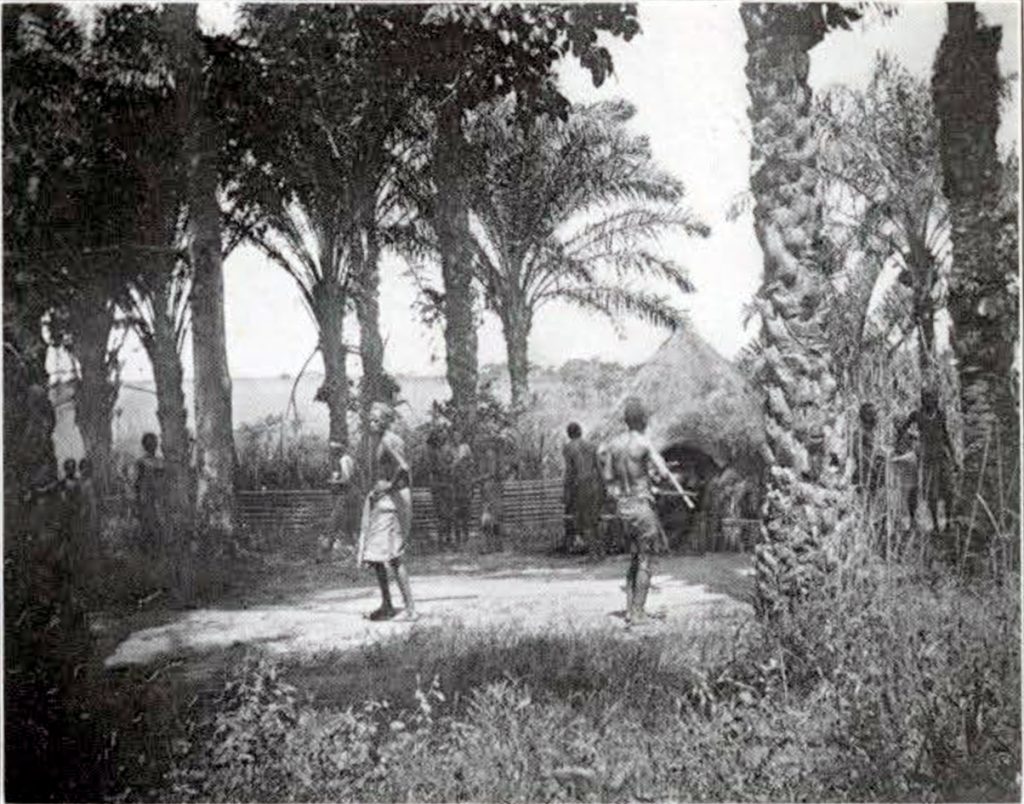

Some musical instruments are used only on special occasions. In Fig. 17 we see a Babunda funeral; the man in front plays a sort of rattle which consists of the stem of a palm leaf, hollowed, the edge of which has been cut out so as to resemble the teeth of a saw. Over this a broom of rigid rushes is rubbed; the sound obtained, if not pleasant, is certainly quaint. The friction drum (Fig. 16) is played when boys are initiated into the state of manhood and in former times was (and possibly even now secretly is) associated with human sacrifice; it is called alternately “the village leopard” and “the lion.”

The Batetela tribe are great drummers. Their drum is cut out of a single piece of wood and gives six different sounds according to the place where it is hit with the rubber-coated drum stick. It is used for signaling and a conventional syllabic alphabet enables the primitive telegraph operator to transmit any message to a distance of several miles. A chief always travels with his drummer and his messages transmitted from village to village will keep him in constant contact with his home.

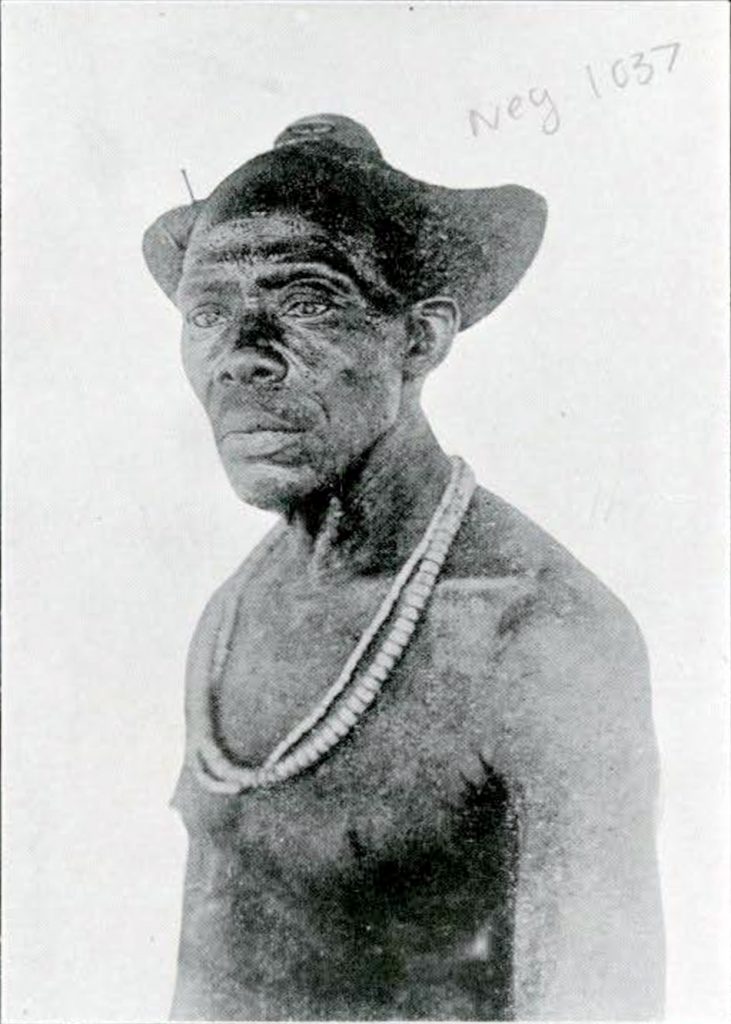

The artistic capacity of the African is displayed by no tribe to a greater extent than by the Bushongo. Fig. 18 shows the king of this country, who claims to be the 121st descendant in an unbroken line of rulers. He stood for the idea of national unity and greatness and when, by the arrival of the white man, the power was taken from him, the kingdom of Bushongo, which for centuries occupied in Central Africa the same position that Rome of the Augustan period held in Europe, fell to pieces and its glory departed from it forever. Such is the price we exact from people who have never harmed us, for giving them a civilization which is sure to disagree with them and to lead to their extinction.

Since the principal part of the collection now exhibited in the Museum comes from that wonderful people, the Bushongo, I desire to say a word about the art of this tribe in particular. The Bushongo, or more correctly the Bashi-Bushongo (meaning “people of the country of the throwing knife”) inhabit the district of the Belgian Congo bounded on the north and east by the Sankurn river, on the west by the Kasai. The name by which they are generally known to Europeans is Bakuba. This, however, is a foreign, Luba, term and is never applied by the Bushongo themselves; it means “people of the thunderbolt.” The Bushongo nation is composed of seventeen sub-tribes, most of which are represented by specimens in the collection now exhibited in the Museum. Besides these there arc three independent Bushongo nations; the Isambo, who revolted and made themselves independent in the seventeenth century, and the Bakonge and Bashilele, representing an earlier wave of immigration; the two latter may be considered as the primitive Bushongo.

Museum Object Numbers: AF395 / AF463 / AF393

Image Number: 893

Museum Object Numbers: AF494 / AF489 / AF507 / AF490

Image Number: 885

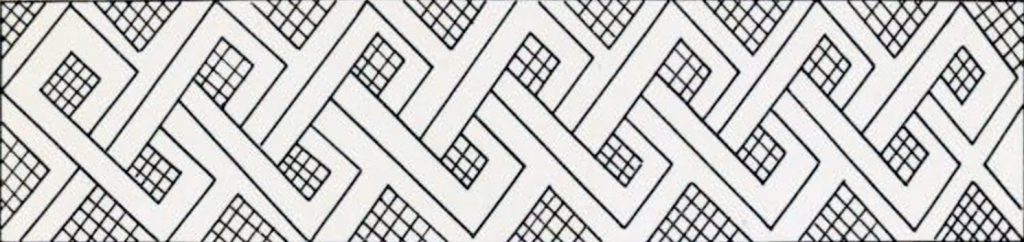

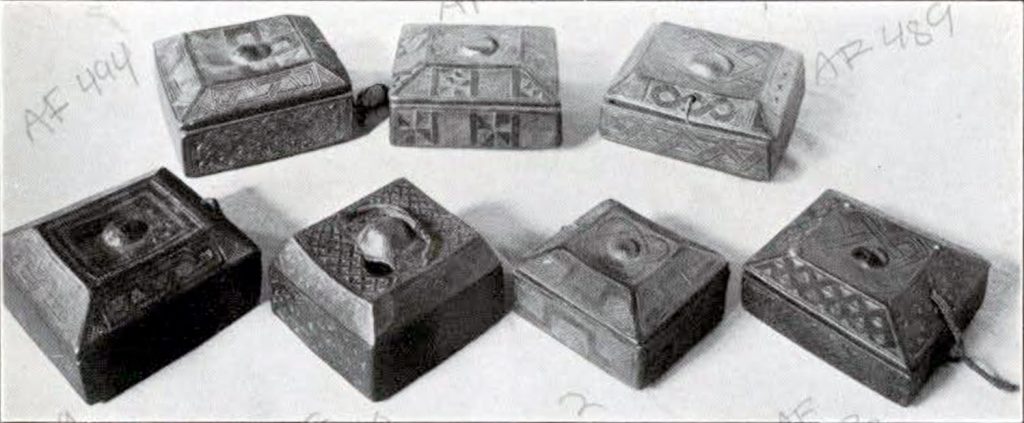

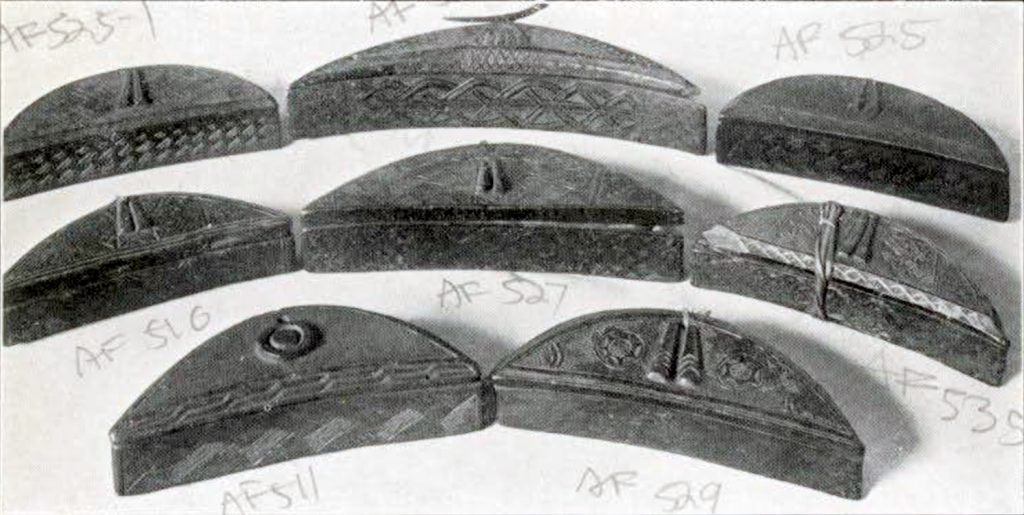

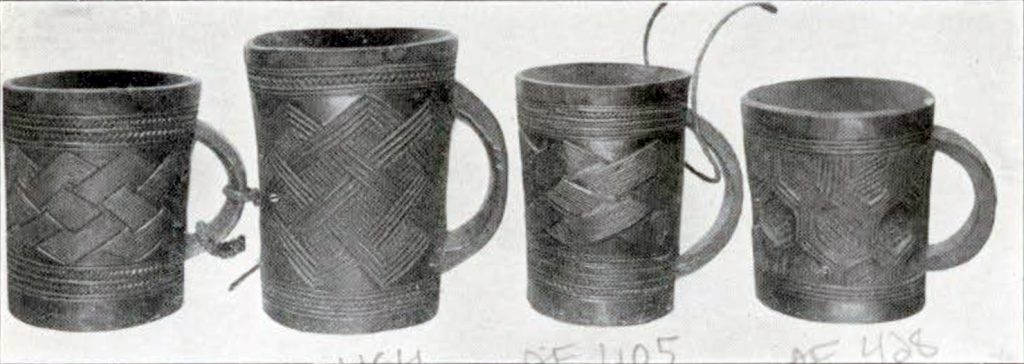

The Bushongo are among the most skillful carvers of Africa. Speaking generally, the forms adopted by them are remarkable for the sense of proportion which they exhibit; hardly a single example can be found, especially among the older specimens, which is not graceful and harmonious in outline. A striking illustration of this statement may be seen in the drinking cups shown in Fig. 19 and in the beautiful pigment boxes Fig. 20. The same sense of proportion is found in their metal work. Next in interest comes ornamentation and this opens a subject which could he treated at almost any length owing to the variety of patterns and the universality of their application. The very skin of the female population does not escape what they consider embellishment. The horror vacui is a marked characteristic of the Bushongo and consequently all their utensils are covered with graceful designs. But though in some cases every square inch of an object is covered with ornamentation, it very rarely appears overloaded; the keen sense of proportion possessed by these Africans extends also to the covering of a definite space with appropriate ornamentation. The outlines are bold and certain and there is rarely any trace of weakness in them.

The ornamental designs of the Bushongo are borrowed from the natural world or from designs derived from textile art ; the prevalence of textile patterns in their wood carving is remarkable and renders any separate classification of carved and woven designs impossible. Some decorations are taken directly from nature; chief among these is a representation of the human face. The most frequent however are the varieties of the design called Bambi (antelope). In one form it consists of an entire head and is constantly found as a detail on pipe-stems. Other forms of this pattern consist in the horn or the horns of the antelope, depicted singly, in pairs, or in groups of any number. Two reptiles are constantly appearing in Bushongo art, the tortoise and the iguana. The former is called Mayulu, and is sometimes found as an ornamental knob, or, more frequently, as a hexagonal design derived from the scales of the carapace of the tortoise. The iguana, Lebene, is usually found carved on drinking horns; sometimes the complete animal is shown, but mostly the spurred forefeet, or even one foot alone, in a highly conventionalized form. The carving of horn with the soft iron tools at the disposal of the Bushongo is a remarkable achievement; these drinking horns are reserved for successful warriors; no one who has not slain an enemy in battle or a leopard is allowed to drink from them.

So far the question of Bushongo art has been fairly straightforward, but the task of dealing with the patterns derived form weaving and kindred crafts is far otherwise. Not that it is not easy to refer these designs at once to their origin, as a glance at the illustrations will show, but it is difficult to understand the native system of nomenclature and any attempt at explanation must be somewhat complicated. The reason for this difficulty lies in the fact that the Bush-ongo do not look at a pattern from the same point of view as we do; they do not regard the design as a whole, hut reduce, as it were, each pattern to its lowest elements, and pick out one of these as the essential feature; the name of this they then give to the whole pattern. Now patterns, like many of these, obtained by breaking various designs of weft at regular intervals, and built up of small details, which occur in various combinations in a number of different patterns, are quite dissimilar in general effect, so that two natives may give different names to the same design, owing to the fact that a different element appealed to the eye of each as the leading characteristic of the pattern. This occurs if the two natives are of different sex: the man sees the design of the wood carver’s, the woman of the embroiderer’s point of view.

I will not enter into the intricate paths by which alone one can come to understand the derivation of the different names of designs. I ventured to go into some details of Bushongo art because the quality of the Bushongo decorations is so remarkable and because the native point of view with regard to the classification of patterns is an extremely interesting physiological question. Enough has been said to show that the acquisition of these objects is of considerable value, not only from the scientific, but also from the artistic point of view.

E. Torday

Museum Object Numbers: AF509 / AF525 / AF510 / AF527 / AF535 / AF511 / AF529

Image Number: 884

Museum Object Numbers: / AF412 / AF405

Image Number: 890

Image Number: 1037